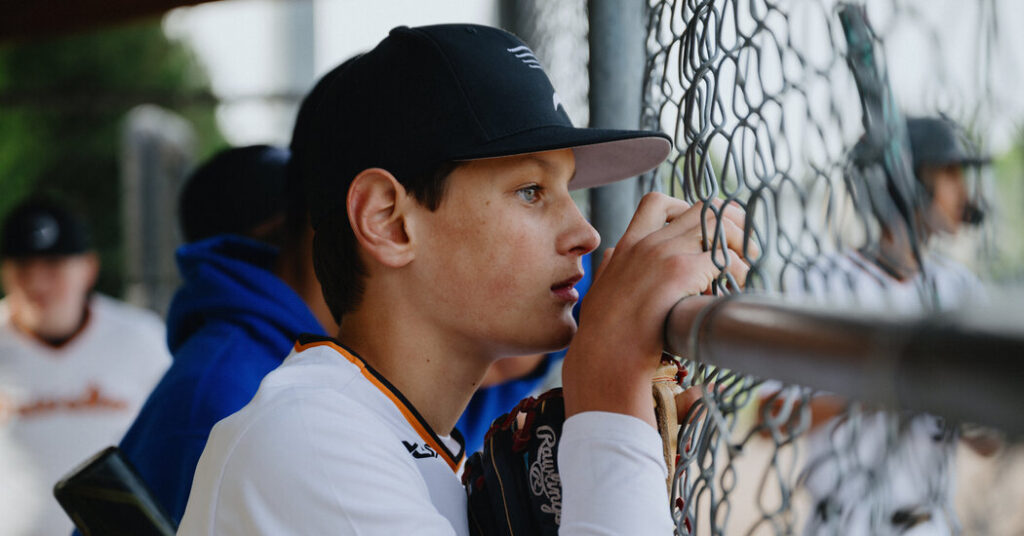

Like many mothers in Southern California, Paula Gartin put her twin son and daughter, Mikey and Maddy, into youth sports leagues as soon as they were old enough. For years, they loved playing soccer, baseball and other sports, getting exercise and making friends.

But by their early teens, the competition got stiffer, the coaches became more demanding, injuries intervened and their travel teams demanded they focus on only one sport. Shuttling to weekend tournaments turned into a chore. Sports became less enjoyable.

Maddy dropped soccer because she didn’t like the coach and took up volleyball. Mikey played club soccer and baseball as a youngster, then chose baseball before he suffered a knee injury in his first football practice during the baseball off-season. By 15, he had stopped playing team sports. Both are now in college and more focused on academics.

“I feel like there is so much judgment around youth sports — if you’re not participating in sports, you’re not doing what you’re supposed to be doing as a kid,” Mrs. Gartin said. “There’s this expectation you should be involved, that it’s something you should be doing. You feel you have to push your kids. There’s pressure on them.”

Youth sports can have a positive effect on children’s self-esteem and confidence, and teach them discipline and social skills. But a growing body of recent research has shown how coaches and parents can heap pressure on children, how heavy workloads can lead to burnout and fractured relationships with family and friends and how overuse injuries can stem from playing single sports.

A report published by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2024 showed how overuse injuries and overtraining can lead to burnout in young athletes. The report cited pressure by parents and coaches as additional risk factors. Another study in the Journal of Sport & Social Issues highlighted how giving priority to a win-at-all-costs culture can stunt a young athlete’s personal development and well-being. Researchers at the University of Hawaii found that abusive and intrusive behavior by parents can add to stress on athletes.

Mental health is a vast topic, from clinical issues like depression and suicidal thoughts to anxiety and psychological abuse. There is now a broad movement to increase training for coaches so they can identify signs and symptoms of mental health conditions, said Vince Minjares, a program manager in the Aspen Institute’s Sports & Society Program. Since 2020, seven states began requiring coaches to receive mental health training, he said.

Domineering coaches and parents have been around for generations. But their pressure has been amplified by the professionalization of youth sports. A growing number of sports leagues are being run as profit-driven businesses to meet demand from parents who urge their children to play at earlier ages to try to improve their chances of playing college or pro sports. According to a survey by the Aspen Institute, 11.4 percent of parents believe their children can play professionally.

“There’s this push to specialize earlier and earlier,” said Meredith Whitley, a professor at Adelphi University who studies youth sports. “But at what cost? For those young people, you’re seeing burnout happen earlier because of injuries, overuse, and mental fatigue.”

The additional stress is one reason more children are dropping out. The share of school-age children playing sports fell to 53.8 percent in 2022, from 58.4 percent in 2017, according to the National Survey of Children’s Health. While more than 60 million adolescents play sports, up to 70 percent of them drop out by age 13.

While groups like the Aspen Institute focus on longstanding issues of access and cost in youth sports, efforts to combat mental health issues for young athletes are an emerging area. In recent years, professional athletes like Naomi Osaka and Michael Phelps have shined a light on the issue. But parents who want to teach their children the positive parts of playing sports are finding that some of the worst aspects of being a young athlete are hard to avoid.

That was apparent to the parents who brought their sons to hear Travis Snider speak at Driveline Academy in Kent, Wash., one Sunday last spring. Mr. Snider was a baseball phenom growing up near Seattle and was taken by the Toronto Blue Jays in the first round of the 2006 Major League Baseball draft.

But he finished eight unremarkable seasons as an outfielder and played his last major league game at 27. While attempting a comeback in the minor leagues, he worked with a life coach to help him make sense of why his early promise fizzled. He unearthed childhood traumas and unrealistic expectations on the field. In a playoff game as an 11-year-old, he had had a panic attack on the mound and was removed from the game.

Though he reached the highest level of his sport, Mr. Snider felt as if distorted priorities turned baseball into a burden, something he wanted to help others avoid. Last year, he started a company, 3A Athletics, to help children, parents and coaches develop healthier approaches to sports that include separating professional aspirations from the reality that most young athletes just want to get some exercise and make friends.

“We as a culture really blended the two into the same experience, which is really toxic for kids as they’re going through the early stages of identity formation,” Mr. Snider said. “You have a lot of parents who are sports fans that want to watch youth sports the same way they watch pro sports without recognizing, Hey, the thing I love the most is out there running around on the field.”

He added, “We’ve got to take a step back and detach from what has become normalized and what kind of vortex we get sucked into.”

Driveline Academy, an elite training facility filled with batting cages, speed guns, sensors and framed jerseys of pro players, might be the kind of vortex Mr. Snider would want people to avoid. But Deven Morgan, who is the director of youth baseball at Driveline, hired 3A Athletics to help parents and young athletes put their sport in context.

“It’s part of a stack of tools we can deploy to our families and kids to help them understand that there is a structural way that you can understand this stuff and relate to your kid,” he said. “We are going to get more out of this entire endeavor if we approach this thing from a lens of positivity.”

During his one-hour seminar, Mr. Snider and his partner, Seth Taylor, told the six sets of parents and sons how to navigate the mental roadblocks that come from competitive sports. Mr. Snider showed the group a journal he kept during the 2014 season that helped him overcome some of his fears, and encouraged the ballplayers to do the same.

“It’s not just about writing the bad stuff,” he said. “The whole goal is to start to open up about this stuff.”

Mr. Taylor took the group through a series of mental exercises, including visualization and relaxation techniques, aimed at helping players confront their fears, and for parents to understand their roles as a support system. His message seemed to get through to Amy Worrell-Kneller, who had brought her 14-year-old son, Wyatt, to the session.

“Generally, there’s always a few parents who are the ones who seem to be hanging on too tight, and the kids take that on,” she said. “At this age, they’re social creatures, but it starts with the parents.”

Coaches play a role, too. The Catholic Youth Organization in the Diocese of Cleveland has been trying to ratchet down the pressure on young athletes. At a training session in August, about 120 football, soccer, volleyball and cross-country coaches met for three hours to learn how to create safe spaces for children.

“Kids start to drop out by 12, 13 because it’s not fun and parents can make it not fun,” said Drew Vilinsky, the trainer. “Kids are tired and distracted before they get to practice, and have a limited amount of time, so don’t let it get stale.”

Coaches were told, among other things, to let children lead stretches and other tasks to promote confidence. Track coaches should use whistles, not starting guns, and withhold times from young runners during races.

“We’re trying not to overwhelm a kid with anxiety,” said Lisa Ryder, a track and cross-country coach for runners through eighth grade. “C.Y.O. is not going to get your kid to be LeBron.”

Ken Belson is a Times reporter covering sports, power and money at the N.F.L. and other professional sports leagues.

The post As Youth Sports Professionalize, Kids Are Burning Out Fast appeared first on New York Times.