The following is adapted and excerpted from “Foxes for Everybody: Twenty-Four Hours of Early Motherhood,” to be published by Northwestern University Press on Jan. 15.

What, I wondered, was wrong with me?

Everyone — relatives, friends with older kids, people in line at the grocery store — repeated the same chorus with slightly different words. “It goes so fast.” “You blink and they’re big.” “Enjoy these days, because they’ll be over before you know it.”

But these days weren’t going fast, not at all. They were moving impossibly slowly. Like molasses, if molasses had been awake for nearly twenty-four hours.

After our newborn son woke, before the sun was up, I’d count the hours until I could reasonably go to bed. If I made it until the sun went down, that would be, roughly … fifteen hours. Fifteen hours of diapers to change and feedings and mysterious cries to decipher, plus all the regular tasks of laundry and showering, grading and course prep. This was a deflating realization to have before the sky was light.

And I was lucky — I adored my baby, delighted in him, felt lifted each time I held him. Yet the days dragged. It seemed impossible they’d ever go quickly. What was everyone talking about? What was I doing wrong?

By late April, a few months into parenting, the days hadn’t gotten any shorter, but we’d learned how to manage them a little better. My husband and I, both writers and English professors in Mississippi, were scheduled to give a joint reading at a college in West Virginia. The plan was to drive up, do the event, then continue on to Delaware, where we’d spend part of the summer visiting family at the beach.

“The sky looks weird,” said my husband. We’d been driving for a few hours. Reports had been calling for dangerous weather.

“It’s looked weird all day,” I said, craning around into the back seat to jiggle our fussing son’s toes. He was 4 months old, and — we were learning — not a fan of road trips.

But my husband was right: The sky was striated, a darker layer of clouds and a lighter layer. “I think we should pull over,” he said, and turned into the parking lot of a small motel outside Cullman, Alabama.

Inside the lobby, I sat down to nurse our son while my husband checked the weather. Suddenly the door opened and in ran two women, yelling, “It’s out there, it’s coming!”

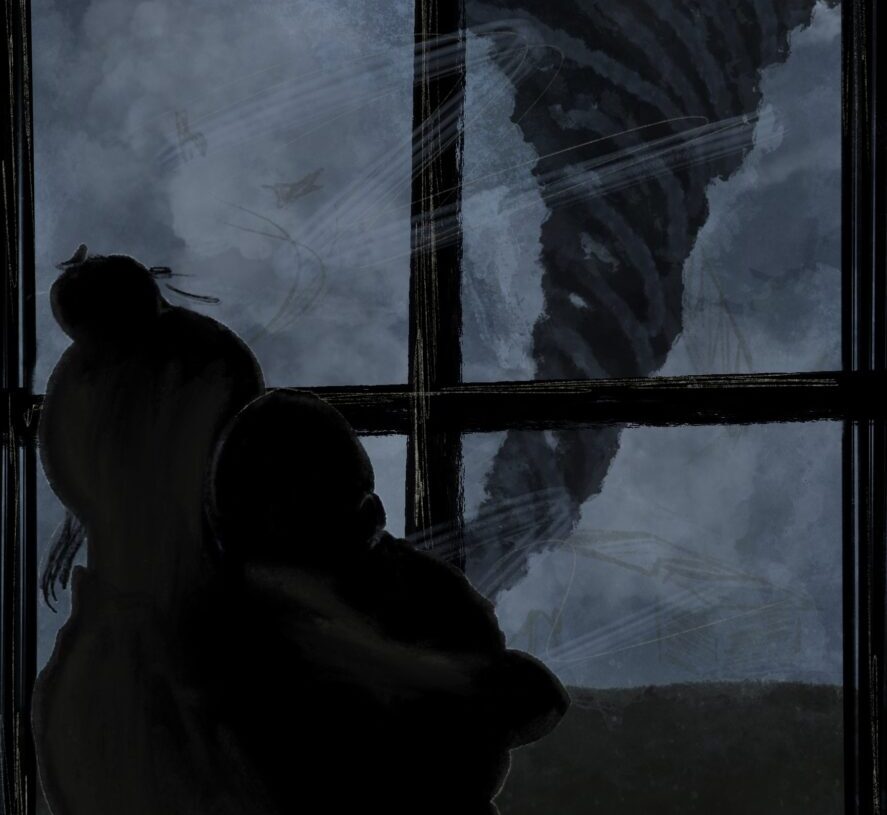

Everything tilted in that moment. There was an actual tornado out there. It was coming. I was holding my baby, and a tornado was coming.

Everyone ran for the bathrooms, the most interior windowless space. I crouched against the tile wall, holding our wailing son, covering him with as much of my body as I could, while my husband tried to cover me. The power cut out. On the opposite side of the wall, people were screaming. This is it, I thought. This is how it ends.

It seemed impossible. Our son was new — so, so new — and we were supposed to have years ahead of us. But suddenly time had sped up like a centrifuge, and what was supposed to be a lifetime was compressed to this Days Inn bathroom, this abrupt stopping. It was impossible.

But it was happening. Outside the bathroom the screaming didn’t stop. Inside the bathroom our son kept howling.

After a few more minutes, we heard a woman call from the lobby that everyone could come out. The tornado had passed, she said. We stood, my legs shaking so bad that I sank into a nearby armchair as soon as we emerged from the bathroom. “I watched it go by,” said the woman. “It was right there.”

We couldn’t stay where we were — the motel was small and flimsy — but driving for any real distance was out of the question. The clouds were still roiling. The air was thick.

We’d lost phone service, so without any concrete information to go on, we buckled our son back into his car seat and set out for the closest sturdy-looking structure we could find. We passed a wrecked gas station, its metal awning flapping in the wind. I scanned the sky while my husband drove. We didn’t speak. Off to the right, I spotted a big chain hotel, the kind that serves free cornflakes and prefab Danish pastries for breakfast. “There,” I said, pointing, and he nodded and turned.

Inside the hotel, the power was out, as it was all across town. People drifted aimlessly around the lobby — some not travelers, we learned, but locals who had lost their homes. “What have you heard?” we asked the front desk workers. But no one knew anything. Rumors ricocheted: Someone had heard the courthouse was gone. Someone had heard Tuscaloosa had been leveled. Someone had heard there was a huge one coming, headed directly our way.

All day, the sirens sounded. Sometimes they were warnings; other times they were ambulances. When the warning blares would start up, we’d scramble under the concrete stairwell with our baby and other scared people to wait out the latest threat.

We didn’t know what time it was. A few people wore watches, but we didn’t bother to ask. Time had ceased to make sense. It had sped up, and then it had disappeared. It didn’t exist. There was only right now, and the waiting to see if right now continued into the next right now. We couldn’t let ourselves think beyond that.

I’ve forgotten many details about that day. Here are some that I remember:

I remember that I had two tricks that calmed my son down in the stairwell: One was to recite “Dr. Seuss’s ABC” over and over, and the other was to sing Bob Dylan’s “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.”

I remember that the stairwell had very nice acoustics.

I remember writing a note to my sister, instructions on how to find a journal I’d been keeping about our son’s first months in the event that he survived this but my husband and I didn’t. I put the note in my purse, figuring someone would look there for identification if the worst happened.

I remember that everyone in the hotel was hungry, and there was no way to get food, until one guy said, “Hey, they have breakfast stuff here,” and walked into the kitchen and came back with a tray of apples and bananas and muffins. We all fell on it like animals.

I remember that much later, sometime that night, after countless cycles of stairwell crouching, the sirens stopped and we stepped outside and everything was different. There were stars. The air was cool. Cold, even. And even without weather reports or news updates, we knew it was done.

I remember that we went to the room where the trays of food were sitting, and someone had found and lit candles everywhere. Our unspeakably vast relief made that soft flickering the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.

I remember that someone gave us a flashlight, and we climbed several flights of stairs in the dark to our room.

I remember nursing our son in bed sometime after midnight, my husband sleeping next to me, while I watched the total blackness outside our window. My body was ringing with awareness — of the weight of our son in my arms, the warmth of my husband beside me, the three of us very, very much alive and very, very much together.

The next morning, we’d drive out of town past wreckage and rubble. We’d see massive trees uprooted and on their sides. Brick buildings crumbled, roofs gone. Later still we’d learn that there was wreckage like this and worse all over the South — in Tuscaloosa, in Birmingham, in Smithville, in Cordova. We’d learn that from April 25 to April 28, the four-day stretch now termed the 2011 Super Outbreak, there were 362 confirmed tornadoes. Of those, three were EF5s, the strongest and most destructive category of tornado, all on April 27. Before that day, there had been no EF5s anywhere in the world for three years. Twelve of the tornadoes, including the one that hit Cullman, were EF4s.

During the outbreak, 321 people throughout the South died in terrible, violent ways; thousands more were injured; more still lost homes, pets, wedding photos, baby shoes and every single book and sweater and lamp and quilt.

But that night I knew none of that. That night I knew only that it was some time in the early morning. I could feel the minutes passing, steadily, calmly. Time had come back, and just like always, it wasn’t going fast. It was slow again, and I breathed in that slowness and breathed in my baby and breathed in the possibility of the next days and weeks and months: the boardwalk fries doused in vinegar, the sharp and precise cry of the herring gulls, the salt air smell, the still-dark early mornings, the diaper changes, the dinners that would get cold because of fussing or feedings, the everything-new faltering I’d do again and again, all of it, all of it. We were absurdly, obscenely lucky. There were so many minutes. There would be, somehow, so many more.

The post A tornado was coming. I was holding my baby, and a tornado was coming. appeared first on Washington Post.