Have you ever found yourself in a new place and realized you don’t quite fit in? Your shoes, which made sense at the office, are not quite the right ones for the date after work in a different part of the city. Your hairstyle, which felt normal when you left your hometown, suddenly labels you uncool in a new city.

Or perhaps you’ve had the opposite experience? You feel out of place in your day-to-day circle and dress in hopes that someone with taste as refined as yours will see your attempts to distinguish yourself in your natty suits.

Most of us have at least a passing acquaintance with the push and pull between the desire to fit in and the urge to stand out depending on the setting. Everyone, as some point, discovers the subtle sartorial codes governing their communities and must decide how much to adopt or reject them.

“People are not always aware of their desire to sub-classify,” said Ari Versluis, one half of the duo behind the “Exactitudes” photo series, which he began in 1994 with his friend Ellie Uyttenbroek.

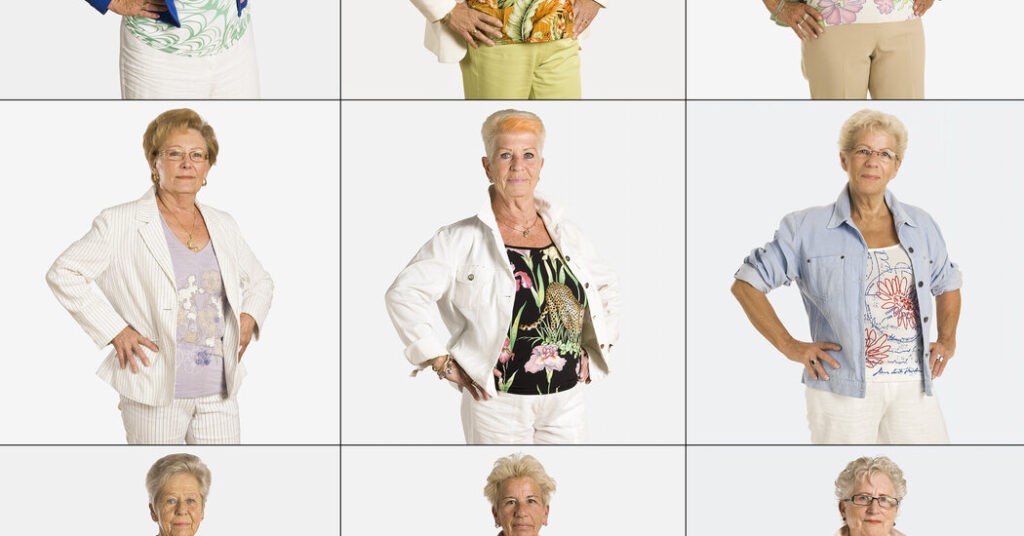

The two have made those sub-classifications the basis of their three-decade-long art project, which now exceeds 200 groups arranged by visual likeness. Each category features 12 individual portraits organized in a grid, named and arranged with the precision of butterflies in a entomologist’s case.

To flip at random through “Exactitudes” (a portmanteau of exact and attitudes) is to be struck by the cleverness and care the artists have taken in selecting their subjects. Looking through each grid is like playing a game. Your eyes dart from frame to frame, in search of the subtle deviances in hairstyles and the way body language speaks volumes.

Now, on the occasion of publishing the seventh and final edition of “Exactitudes,” the duo is putting the project to bed. After three decades of collaboration, they look back in fondness at the time capsules they’ve created.

‘The street is always the answer.’

When they met as art students in Rotterdam, Mr. Versluis was studying photography and Ms. Uyttenbroek was a fashion major who didn’t want to go the traditional design route. “I loved making clothes, but I didn’t like the industry, even then,” she said.

They enjoyed observing how people fashioned themselves in the real world, so they stationed themselves in different neighborhoods, chasing people down on the street when they liked their looks. This became their approach wherever they went.

“We start by inviting the people to the studio,” Ms. Uyttenbroek said of their process. “We get to know them, and most of the time we take about 20 images.” When it comes to interesting things happening in fashion, Mr. Versluis said, “the street is always the answer.”

Unlike the classic street-style images of someone like Bill Cunningham, Mr. Versluis and Ms. Uyttenbroek strove from the beginning to make art, as opposed to straight reportage. On occasion they ask subjects to return to the studio for a reshoot if they find a better way to capture them.

When they don’t have a firm handle on a subculture they’re photographing, they listen. “Some of the groups, you start and you have a vague idea about them,” Mr. Versluis said. By listening, he said, “you get educated, especially when it’s a super-niche culture or something new.”

Sometimes they wait many days on location before finding enough willing participants. Sometimes the people in the grid know each other, but not always. For the most part, they say, participants are flattered to be included in the project.

‘The diverse human experience of getting dressed.’

Both artists have always worked independently and will continue to do so, though they did not rule out the possibility of a returning if a tantalizing commission comes along. Since they began shooting “Exactitudes,” the world has transformed from an one dominated by analog technologies to one ruled by digital algorithms. Where they were once perceptive humans finding patterns among the other humans, social media now serves up endless micro-trends to viewers the world over. In some way the magic of their project has been consumed by TikTok and Instagram.

Ms. Uyttenbroek feels they offer something quite different. “We were not only interested in fashion trends,” she said. “We think of the next 10 years, not the next season.” They also train the camera on older people, children and people outside of any mainstream algorithm.

Though they feature people of all income brackets, they have found rich people more challenging to capture “because so many of them live in compounds, far from the street.” Ms. Uyttenbroek said. But she feels that the work is “not about generalizing” or suggesting that people are like clones, “but the opposite.” Their interest lies in the diverse human experience of getting dressed.

‘Stay as open to others as possible.’

“Identity grows on you,” Ms. Uyttenbroek said. “The older you get, the more it becomes you.” She appreciates how much better she understands herself now in her 50s than she did as a younger person. She said that speaking with thousands of people about how they define their style has made her appreciate the challenges of “really knowing what you want to wear.”

Mr. Versluis, a self-described “punk and club kid to his core,” tries to “stay as open to others as possible.” He looks for authenticity, though he is quick to acknowledge that he’s not sure if such a thing exists. “People, when you speak to them, always turn out to be different than you assumed,” he said.

The final edition of “Exactitudes” is available at exactitudes.com or at Dover Street Market in New York.

The post We’re All Unique. Or Are We? appeared first on New York Times.