President Trump seems determined to transform America into a straight white Christian nation. He filters our history through this harsh sieve, trapping and discarding every complexity and nuance.

Indigenous people don’t often appear in his increasingly deranged racist rants, but they are suffering the same racial profiling as other brown-skinned American citizens. Immigration and Customs Enforcement can’t contrive a “home country” to assign them for deportation. By definition, these are Native Americans.

Notably — and purposefully — missing from Trump’s October Columbus Day proclamation are the people who were already here — at least 50 million Native people in the Americas when Columbus “discovered” the North American continent he never actually set foot in. Trump has Columbus planting “a majestic cross in a mighty act of devotion … setting in motion America’s proud birthright of faith,” a “noble mission: to … spread the Gospel of Jesus Christ to distant lands.”

The White House Thanksgiving proclamation also centers on faith and conquest. Not even the old gauzy fictions about the Wampanoags feasting in harmony with colonists, but only praise and gratitude for “the pilgrims who settled our continent” and “the pioneers who tamed the west.”

Trump’s only acknowledgments of the complicated consequences of the arrival of Columbus are jabs at the “left-wing arsonists” who remind us that what Trump calls “the ultimate triumph of Western civilization” could also be called genocide. His accusation upends the truth; it’s Trump who is demanding the incineration of history.

I’m with the “arsonists.” The wrenching transfer of territory and power from hundreds of Indigenous cultures to the United States of America is fundamental to our history. Native people held the interior of the continent for centuries, holding on to their homelands — trading, moving, shifting alliances, fighting, rebelling, dying — until finally being overwhelmed by the surging numbers of colonists.

Native people didn’t disappear. According to the census, their numbers came close to doubling between 2010 and 2020 as more Americans claimed and honored Indigenous ancestry.

As I watch Trump’s efforts to erase all people of color from our national story, I keep wanting to counter with the remarkable truths of Native survival and grit. I’ve got some history here.

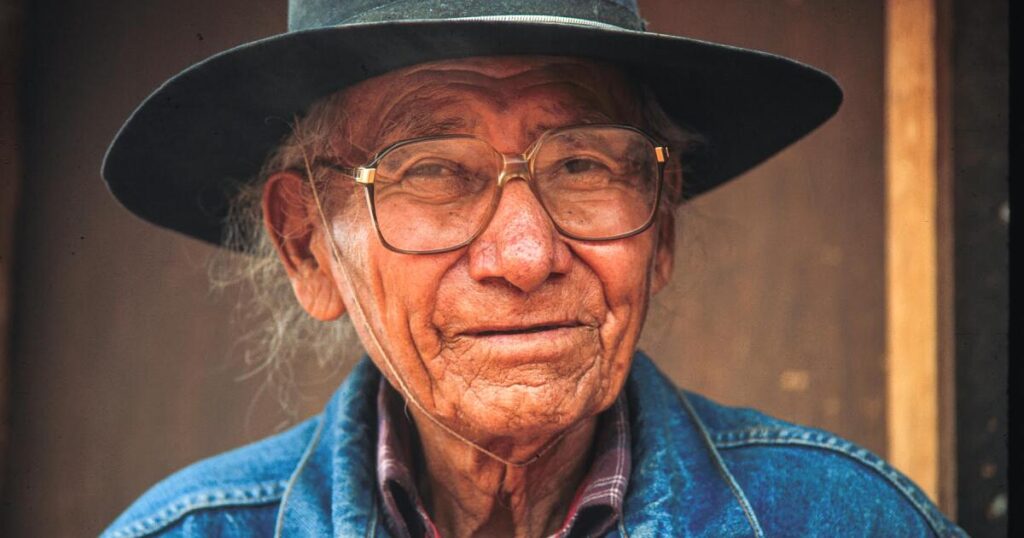

When I began interviewing Southwest Indigenous people for book projects in the 1980s, Native folks insisted that I understand tribal sovereignty. As a naïve white man, I had a lot to learn. Treaties matter, even if they were signed 200 years ago and repeatedly violated. Elders told me of their struggles to keep their culture vital and retain their language in the face of heartbreaking assaults and trauma.

Pride, intense pride, counters marginalization.

As Santa Clara Pueblo historian Rina Swentzell told me, “It’s good to change, it’s good not to change — they always have to be brought together in some balance, so that they create a whole.” For Native people, that whole flourishes in community.

Recently, I’ve been reminded repeatedly of these persistent certainties that I heard from so many tribal members who have lived their lives in the unbroken stream of Indigenous continuity that stretches from the past right through the present and will stretch into the future.

Take Steve Darden. He was barely 30 when I met him more than 40 years ago, the first-ever Indigenous City Council member in Flagstaff, Ariz. — a sort of Diné precursor of Zohran Mamdani — and already a clarion voice for his community. Darden is now an elder, a traditional practitioner, a long-time member of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission and a Luce Foundation Indigenous knowledge fellow.

You can meet Darden on YouTube, speaking eloquently for an hour and a half to the Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery. His articulation of Diné values mirrors teachings we might have heard in a ceremonial hogan two centuries ago.

Amelia Flores was my long-ago contact at the Colorado River Indian Tribes, a young Mohave woman in charge of the tribal library. She was an advocate for her people then, and, today, she’s tribal chair — the first woman to be elected leader of the tribe.

The Colorado River Indian Tribes have the most senior rights for Colorado River water in Arizona, and Flores is widely quoted as an authoritative voice in Native water rights. Her tribal council recently passed a resolution granting personhood to the Colorado River. Flores is writing traditional values into law: “What binds us all at CRIT is the river itself,” she says. “It is a gift to our members from the Creator and we have a sacred obligation to protect and preserve it for the future.”

In 1984, Lucille Watahomigie, then director of the Hualapai bilingual education program, set me up with nonstop interviews with everyone from elders to parole officers to the tribal chairman when I visited her northern Arizona reservation on the rim of the Grand Canyon. Watahomigie later served as principal and superintendent of Hualapai schools. This year, she turned up on the cover of the Grand Canyon Trust magazine (she’s turning 80!), a celebration of her lifelong dedication to passing along Hualapai plant knowledge generation to generation.

Young people become elders, low-level officials rise into leadership. Teachers repeat the mantras of relationship and reciprocity with the nonhuman natural world. The continuity with the past is unshakable. As Jim Enote, Zuni Pueblo artist and advocate, introduces himself, “I’m a 600th-generation Colorado Plateau resident.”

Trump cannot erase this strength, this history, the Indigenous core of our continent.

When he says “America First,” he means Donald Trump first, white people first, and everyone else in the world cut loose to fend for themselves. Native tradition teaches values that invert this gold-plated Trumpian individualism: kinship, reciprocity, interdependence, healing. Like all teachings, these are aspirational.

But imagine an America that puts community first. I want to live in that future, and I’m banking on my fellow citizens to realize that’s the only way out of our current vortex of selfishness and shortsightedness. Native cultures overwhelmingly favor relationship over transaction. We would do well to heed them.

Utah writer and photographer Stephen Trimble is the author of “The People: Indians of the American Southwest.”

The post Native people refuse to be erased from America’s past, present or future appeared first on Los Angeles Times.