Like many Americans, most countries are in a lot of debt.

Developing countries, alone, carry nearly $31 trillion worth of debt. Enough debt to give everyone in the world a check for $3,750. Or to pay for Jeff Bezos to throw a $50 million wedding in Venice every weekend for the next 11,900 years. Or, at least in theory, to solve world hunger with trillions to spare.

But instead, many countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America are saddled with so much debt that today more than 3 billion people — over one-third of humankind — live in nations that spend more on interest payments than they do on health care or education. This is nothing new. But it’s gotten far worse in recent years as part of a vicious cycle that will be all too familiar to most Americans who’ve ever fallen behind on a credit card bill or a student loan payment.

You take out a new credit card to pretend you can pay the old one. No matter how much you pay off each month, somehow the amount you owe seems to grow larger each year. And if a disaster strikes at the absolute worst possible moment — be it a hurricane or a medical emergency — then forget it.

Key takeaways

- Low- and middle-income countries are in a lot of debt. So much debt that many now spend more on interest payments than they do on education or healthcare.

- Once you’re stuck in a debt spiral, it’s almost impossible to climb out. It’s gotten even stickier in recent years as interest rates rose, climate disasters piled up, and the composition of creditors changed to include more private lenders and China.

- Who benefits from the debt spiral? Wall Street lenders tend to charge the highest interest rates, meaning some have gotten rich off of lending to developing countries.

- There’s no silver bullet to fixing the global debt trap. But proposed laws in New York and London, where most sovereign debt is issued, could help prevent the worst abuses. And anything that makes restructuring debt easier could help countries escape the cycle faster.

For poor countries, as with people, debt twists into a financial hole with no end in sight.

“It’s like the Hotel California,” said Penelope Hawkins, senior economic affairs officer at the United Nations focusing on debt and development finance. “You can check out any time you want, but you can never leave.”

And when the crisis gets deep enough, indebted countries stop building hospitals, just like deeply indebted Americans forgo health care and trips to the dentist. The nations defund their schools. Their economies slow. And their credit rating tanks, meaning that any future loans will be even more expensive.

“These aren’t just statistics,” said Joel Curtain, director of advocacy at Partners in Health, which has been pushing for reform to the system for resolving runaway debt. “This crisis is embodied in sickness, ill health, and death.”

To understand a pernicious piece of how this all works, look no further than the handful of Manhattan hedge funds that effectively control the financial fate of some entire countries — just like they may control your mortgage and your own highly profitable credit card debt.

The terms of most countries’ debt contracts — also known as sovereign bonds — are not handled by some international body or within the debtor country, but rather, are split between the jurisdiction of judges in the two largest financial hubs in the world, New York and London. After all, that’s where the money is.

And thousands of miles away, it is ordinary people who face the hidden but profound consequences of that debt deal gone wrong. They are the ones who will hurt the most when the government cuts kick in, when the price of bread doubles, their kids’ classrooms size balloons, and the hospitals go dark.

But as poor countries face down a broader shortage of funding for critical development projects driven by sweeping foreign aid cuts, some activists see a real opening for relief.

Starting on Wall Street.

The debt trap, explained

There is nothing inherently wrong with having some debt.

It costs money to get ahead. If you want a well-paying job, you probably have to go to college. And if you don’t have family who can cover the bill, then you probably need to take out loans.

The same is true for countries. If you want to grow your economy, you’ve got to build schools, staff hospitals, and invest in infrastructure. And if your country is not wealthy to begin with — if you got the short end of colonialism’s stick — then the only way to pay for that is to take out loans.

“No country has grown without some debt,” Hawkins said. “No country has developed without debt.”

Vietnam, for example, was once one of the poorest countries in the world. But a series of economic reforms in the late ‘80s — accompanied by $26 billion in World Bank loans since 1993 — literally catapulted the country into the global middle class, nearly eradicating extreme poverty in the process.

The problem is, the loans that poor countries take out these days have become so expensive — and the growth they’re supposed to fuel is often so sluggish — that they can never pay them back. The interest adds up before the returns come in.

And yikes, has that bill added up over the years.

Developing countries have seen their total debt balloon by almost 160 percent over the past decade. More than 60 of those countries now spend more than 10 percent of their government revenues on interest payments.

Since you’re a responsible news-consuming citizen, this is the moment when you might be wondering: Doesn’t the US owe gazillions of dollars to its creditors, too?

Yes, in fact, it absolutely does.

While Americans say they care about the debt, they don’t vote like they do, though they probably should! But they don’t, largely because a rich country like the United States gets to borrow in its own currency and it can almost always take out more cheap loans to pay off the old ones.

This means that the national debt rarely affects the lives of ordinary Americans. The US does not need to cut Social Security or stop paying for road maintenance to indefinitely manage its debt. Not yet, at least.

But poorer countries lack that luxury.

Just like low-income Americans often contend with backbreaking interest rates if they want to borrow cash, so too do low-income countries. African nations pay an average of 10 percent interest on their loans, whereas interest rates for rich countries like the US are typically under 3 percent.

And this is where we get to Wall Street. Because private creditors like hedge funds and insurance companies increasingly hold the bulk — about 60 percent in 2023 — of low- and middle-income countries’ external debt, a trend that has been rising since 2010.

That wasn’t always the case. For much of the 20th century, when a developing country needed finance, it usually turned to the Paris Club, an informal grouping of Western creditor countries, or newly formed Western-controlled multilateral institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, while working more sporadically with private creditors like banks.

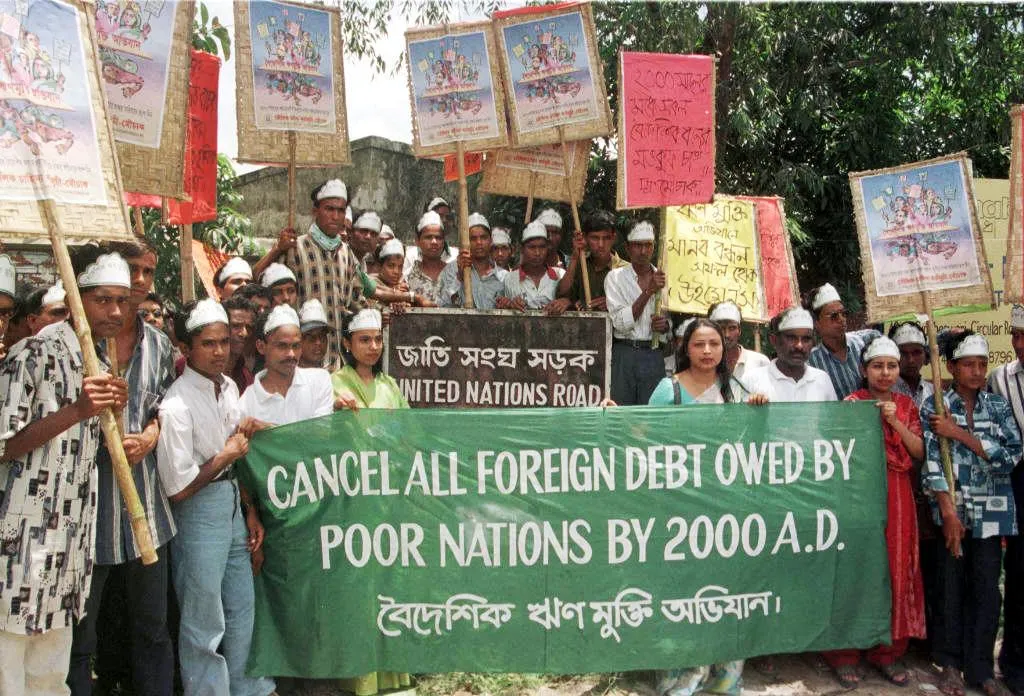

But in the early 2000s, the Paris Club pulled back on lending after a protest campaign endorsed by Bono and the Vatican caused it to forgive billions of dollars in poor countries’ debt. Then, boom — the Great Recession hit and interest rates plummeted, forcing private creditors to start looking for a new way to earn cash.

They found it in poor countries, where they could charge much higher interest rates than they could in rich countries. In fact, bonds became so unprofitable in places like Germany that they entered negative territory a few years after the financial crisis, whereas interest rates across Africa hovered above 5 percent. The modern sovereign debt business was born. And these private companies made a killing on those high-interest loans.

“It’s good business to lend,” said Martín Guzmán, an economist and former economy minister of Argentina. “Almost too good of a business.”

Few countries know that as well as Argentina does. After years of debt drama, a slew of neoliberal reforms compelled by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and a debilitating economic crisis, the country stopped paying off its $100 billion debt on Christmas Eve 2001.

It was the second-largest sovereign debt default in history, one that sent its creditors — from Wall Street barons to pension funds — into a tailspin. Fear of exactly this worst-case scenario illustrates why loans are so expensive for low- and middle-income countries: The higher the risk, the higher the interest rates demanded by lenders. In Argentina’s case, chronic overspending and cycles of inflation have made borrowing especially expensive.

Almost nobody benefits when a country defaults. Lenders have to take a haircut on their loans, while the debtor country has to make painful cuts and becomes a sort of pariah in the global financial world. But there are exceptions.

Most creditors eventually accepted new discounted terms to Argentina’s debt, but others, hoping to make a quick buck and wash their hands of the crisis, sold off their Argentine bonds — or loan contracts — for pennies to the dollar to vulture funds, investors that specialize in hounding debtors for what they’re owed.

You can imagine what came next. The vultures who bought up Argentina’s loans pounced, the most notorious of them being the hedge fund Elliott Management. Elliott sued the bejeezus out of Argentina for nonpayment, even seizing an Argentine naval ship ported in Ghana in an attempt to recoup the loans in 2012.

Muhammed Emin Canik/Anadolu Agency

Creditors who lend to poor and middle-income countries “want to charge high interest rates, but they also demand to be repaid in full when risks happen,” said Tim Jones, policy director of the longstanding advocacy group Debt Justice. “They want to have their cake and eat it too.”

In the end, Elliott won. After a 15-year battle in New York state court — since about half of all sovereign debt is litigated on Wall Street’s turf — Elliott managed to score a highly profitable $2.4 billion settlement, a 392 percent return on the original value of the bonds, but since Eliott paid very little for those bonds, the company earned a profit of 10 to 15 times what it initially paid.

At the time, Elliott’s CEO, Paul Singer, blamed Argentina for its own “sad path” to financial crisis as a “once very impactful country economically” coming out of World War II. “They are imposing damage on themselves way out of proportion to the cost of paying the debt,” he said.

It’s true that Argentina was in part a victim of its own mistakes. But it’s also true that Argentina, which was once one of the wealthiest countries in the world, has never fully recovered. And it was ordinary Argentinians, not those who were making the decisions, who paid the price.

The real cost of repayment

There is no shortage of reasons that poor and middle-income countries fail to pay off their loans, including the most obvious: overspending.

When the southern African country of Zambia defaulted on its debt in 2020, the IMF and other analysts blamed it on years of unsustainable borrowing, corruption, and poorly targeted infrastructure projects underwritten mostly by private creditors and, increasingly, China. There were also factors mostly outside of Zambia’s control, like a drought the year prior that strained the country’s finances to its breaking point, and an extractive economy based around copper mining that developed under colonialism that forces the country to take out more loans when the price of the commodity drops..

“There is a school of thought that whenever a country is in default, it is all the fault of the lenders, and that is usually not the case,” said Gregory Makoff, a self-professed sovereign debt obsessive, author of Default: The Landmark Court Battle Over Argentina’s $100 Billion Debt Restructuring, and a fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation.

As a result, 3.4 billion people now live in the 46 developing countries that spend more — $921 billion in 2024, a 10 percent increase from 2023 — on interest payments alone than they do on health or education, according to the United Nations.

“It is usually the fault of the borrower,” he said, because the borrower is the one who makes the decision to take out a loan, the one who “uses the funds and has to take responsibility for itself.”

But for every handful of nations that stop paying their loans, dozens dutifully take out new loans to pay off their old ones each year.

One reason that debt burdens are so high today is the Covid-19 pandemic, which forced many countries to take out additional loans to keep their economies and healthcare systems afloat.

Another is interest rates. Remember when the Federal Reserve hiked the price of borrowing to try to quell inflation in the US? That didn’t just impact your mortgage rates — it made borrowing that much more expensive for poor countries too.

Add in the war in Ukraine, which drove up energy and food prices globally, and increasingly frequent climate disasters that force countries to borrow even more just to rebuild, and you’ve got a recipe for the worst sovereign debt crisis in decades.

But even as countries’ debt balloons, defaults like Argentina’s are relatively rare these days, largely because nobody wants to be chased by a vulture fund or find themselves locked out of global financial markets. Instead, many countries are digging deep into whatever savings or spending cuts they can muster to pay off those loans.

“Countries are not defaulting on debts,” Guzmán said. “But they’re defaulting on development.”

Developing countries spent $741 billion more on paying back their loans than they received in new finance between 2022 and 2024, the largest gap in 50 years. But despite these payments, their debt has just grown larger, rising at twice the rate of rich countries.

If you’re an austerity hawk, that might sound like a good thing.

These kinds of cuts are compelled by the IMF not because that institution is mean-spirited, but because it’s a way to bring countries closer to eventually paying off their loans and finding a stronger financial footing in the long term.

If your uncle is “drunk and always is running up his credit card and running personal bankruptcy, are you going to blame his credit card lenders and his mortgage provider for his problems?” Makoff asked. “Or maybe he made some bad decisions.”

At the end of the day, the IMF is brought in to “do math” for countries that have “generally made a lot of bad decisions,” said Makoff. “They make sure the money [that comes] in and out adds up” and do their best to avoid catastrophic social spending cuts in the process.

But for billions of people around the world, this kind of fiscal responsibility can also mean hospitals that don’t get built. Schools that don’t get textbooks. Roads that don’t get paved.

Every dollar of interest lining the pockets of Wall Street’s Bonobos pants and fleece-lined vests is a dollar less for development.

“Western governments tend to only see it as a crisis when people stop paying,” Jones said, but “the real crisis is the fact that they are paying and the cost that’s happening through cuts” to service these debts, which he described as “catastrophic for the future.”

And this is more or less by design. For decades, the US-dominated IMF has required countries looking to restructure their debt to impose cuts to social services.

Andrew Renneisen/Getty Images

”

So Malawi’s government has taken out loans. A lot of loans, many of which carry very high interest rates, because lenders don’t trust that the impoverished country will be able to pay them back. Over the past several years, Malawi’s total public debt has soared to above 80 percent of its GDP or around $12 billion, up from 35.5 percent of GDP — under $3.2 billion — a decade ago.

Take Malawi, for example. The landlocked southeast African country, the world’s third poorest per capita, is in the midst of the worst economic crisis in its history. Since 2019, it has faced back-to-back climate disasters, including the region’s worst drought in a century, which has plunged over half of Malawians — most of whom are subsistence farmers — into profound food insecurity.

Long story short, if you want to understand the dystopian and often surreal reality of global debt financing, look at Malawi’s budget for the coming fiscal year. The country will spend just over $440 million — $20 per person — on health care. It will spend just over $770 million on education.

And it will spend over $1.25 billion, more than what it spends on health and education combined, on interest payments. Again, these are just interest payments, which go straight into the pockets of commercial banks and foreign investors who own them.

Given that 75 percent of Malawians live on less than $3 per day, the government can hardly rely on tax revenue, so it will need to borrow even more money to make those payments on time.

And so the cycle continues, and ordinary Malawians suffer the most.

“We don’t have enough doctors. We don’t have enough nurses,” said Makhumbo Munthali, director of partnerships at Partners in Health’s office in Malawi. In Malawi, he said, a generation of trained local health professionals can’t get jobs because the “government is trying to meet austerity measures” imposed by the IMF. Most end up moving abroad for work, leaving the country with just two physicians for every 100,000 people.

“The IMF has been saying that there will be some sort of pain for a while and then later on things will stabilize,” he said. “But that has not been the case.”

Why there’s hope for change

Malawi is far from alone. Almost half of low-income countries are now in or at high risk of debt distress, meaning they’re struggling to pay their loans.

To make matters more complicated, sweeping foreign aid cuts have left many countries scrambling to fill funding gaps this year. Many poor countries normally rely on foreign donors — chief among them, the United States — to subsidize the majority of health and education programs in their country. The United States previously subsidized at least half of all annual health spending in Afghanistan, Somalia, South Sudan, and Malawi. Countries like Nigeria have already begun taking out new loans to keep their health systems afloat.

And so far, it appears that Trump’s new foreign policy prerogative will mean that when the US does choose to fund development, it will increasingly be in the form of loans, rather than grants. China, an increasingly important lender for poor countries — especially in Africa — also conducts much of its foreign aid this way, and has also faced its own criticism for leading nations into debt spirals.

One of Trump’s first actions upon taking office was to stop all US funding to a program that helped vulnerable countries prepare and adapt to climate change. Many of those countries have no choice but to regularly take out enormous new loans in the aftermath of every new disaster, like Hurricane Melissa in Jamaica. It’s a burden that seems to grow every year.

These countries “are piling on debt not to build infrastructure, not to grow, not to develop like other countries,” said Ritu Bharadwaj, a climate finance and resilience expert at the International Institute for Environment and Development, but simply “to rebuild and bring the economy back on track” when disaster strikes.

Sri Lanka, for example, was recently forced to ask the IMF for a multimillion-dollar loan to fuel its recovery in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah last month, even as the country continues to recover after defaulting on its loans in 2022.

At the time, Sri Lanka’s debt crisis forced schools to cancel exams because they ran out of paper. Hospitals canceled surgeries because they ran out of medication. Fuel shortages forced doctors to stitch wounds in the dark and food prices rose by 90 percent, leaving over a quarter of people food insecure.

But if there is one silver lining to the aid cuts, it is that countries struggling widely with debt burdens have gained a powerful new moral argument for changing the system.

If wealthy countries are unwilling to help subsidize what it costs for poor countries to adapt to climate change, Bharadwaj said, then “we really need to at least provide them a fair chance to do it themselves,” because most developing countries spend far more on interest payments than they’ve ever received in foreign aid.

Even some private creditors are calling for change. At recent meetings with bondholders, UNCTAD’s Hawkins said, some acknowledged that pushing countries to keep paying unsustainable debts ultimately hurts everyone — including creditors who want borrowers to stay solvent enough to keep doing business.

For some activists, the solution starts on Wall Street. Over the past few years, organizers in the financial hubs of New York and London have been exploring changes to local law that could shield vulnerable countries from the most egregious debt litigation.

We’re talking about Elliott Management in Argentina. Or more recently, an entity called Hamilton Reserve Bank, which has refused to agree to a debt restructuring plan for Sri Lanka, instead suing the country for $250 million in a lawsuit still ongoing in New York.

The proposed New York state law would offer countries a framework for obtaining relief and restructuring their debt, with provisions against private creditors that attempt to hold out on a deal. Amid a concerted lobbying effort from Wall Street firms, the deal failed to move forward this year, but will be coming up for a vote again in the year ahead.

Even if this bill — and a similar one in London — passes next year, it’s not going to transform the problem overnight. There’s no silver bullet for dismantling the debt vortex that so many poor countries find themselves in — especially if it doesn’t involve significant loan forgiveness.

But anything that makes it easier for countries to renegotiate their debt — which both the New York and London bills aim to do — would be a big win. Unlike individuals or companies, countries don’t have the option of declaring bankruptcy. So when a nation like Sri Lanka can no longer pay its loans, its only option is to head back to the negotiating table with its creditors.

And even when there are no supervillainous vulture funds involved, such renegotiations are “just a monstrous process for a debtor to go through,” said Jones of Debt Justice, citing Zambia, a neighbor of Malawi that defaulted on its loans in 2020 and has been renegotiating its debt ever since.

“My daughter was born around the time the Zambian process started, and she can now read and write,” he said, noting that if New York or London manages to eke out a restructuring bill, then more countries will feel empowered to apply for debt relief.

Without it, they’ll just keep borrowing, often from multilateral organizations like the World Bank, whose loans are ineligible for restructuring and contingent on painful policies that can stifle development in the long run.

And without comprehensive structural reform and genuine debt forgiveness, those countries will never escape. Every “extension of term” on loan repayments may give them a “breather,” said Hawkins, but only delays the inevitable for countries made insolvent by deals that were often rotten to begin with.

“This idea that we can continue to kick the can down the road” is no longer tenable, she said. “That horizon is coming very much closer to us.”

The post How Wall Street helped turn poor countries into permanent debtors appeared first on Vox.