It was October 2023, and F.B.I. agents told Hui Bo not to come to their office.

For his own safety, it would be better to meet in public, he recalled them saying, so he waited near a park in Los Angeles. He was warned that he was being watched by agents of the People’s Republic of China after he commissioned sculptures in protest of China’s government.

“The F.B.I. said that you are in great danger, that we strongly recommend that you move and not live here anymore,” Mr. Hui said in an interview. “That’s when I felt fear.”

Mr. Hui’s story is part of a larger trend, one that federal law enforcement officials said exposes an aggressive new phase in China’s global campaign to silence dissent.

Where once the Chinese state focused on political dissidents and exiled activists, it now targets artists like Mr. Hui, whose creative protests have tested the government’s tolerance and reach, the officials said.

The crackdown has intensified and extended beyond China’s borders since the country’s top leader, President Xi Jinping, rose to power in 2012.

The government has even expanded its influence to elections abroad, including races in New York City, to try to quash criticism of the Chinese state in places where people are more free to speak out than they are in China.

China is not alone in seeking to silence critics abroad.

Russia does it. Iran does it. Saudi Arabia does, too, according to Roman Rozhavsky, the assistant director of the F.B.I.’s counterintelligence division in Washington.

But China, he said, is the most prolific, devoting substantial resources to the effort in the United States. Suppressing dissent is a priority for China’s president, Mr. Rozhavsky said.

“We are seeing more of these cases and we’re seeing the Chinese government be more aggressive in going after people on U.S. soil,” Mr. Rozhavsky said.

The cases involving the artists share a common thread: They were targeted for criticizing President Xi, the Chinese Communist Party, or the workings of the Chinese government.

A spokesman for the Chinese embassy in Washington said that he was unfamiliar with Mr. Hui’s case.

He rejected the claims made by the U.S. Department of Justice that China had been silencing critics abroad, calling it, in a statement, a “completely unwarranted accusation and a malicious smear against China.”

Mr. Rozhavsky said that critics of China have had relatives living in the country threatened by the Chinese government, or that China has hired a person in the United States to intimidate or physically hurt them.

“Their job is to silence people and, unfortunately, it works,” Mr. Rozhavsky said. “It creates this Orwellian climate of fear where people are afraid to speak their mind even though they’re on U.S. soil and they’re just exercising their right to freedom of speech.”

Mr. Hui, 57, left China for Los Angeles in 2017 with his wife and two children. He hoped to give his children a better life, one far from the reach of an oppressive government, he said.

Years after leaving China, disillusioned by its handling of public health crises and its suppression of free expression, Mr. Hui began working with a sculptor in secret.

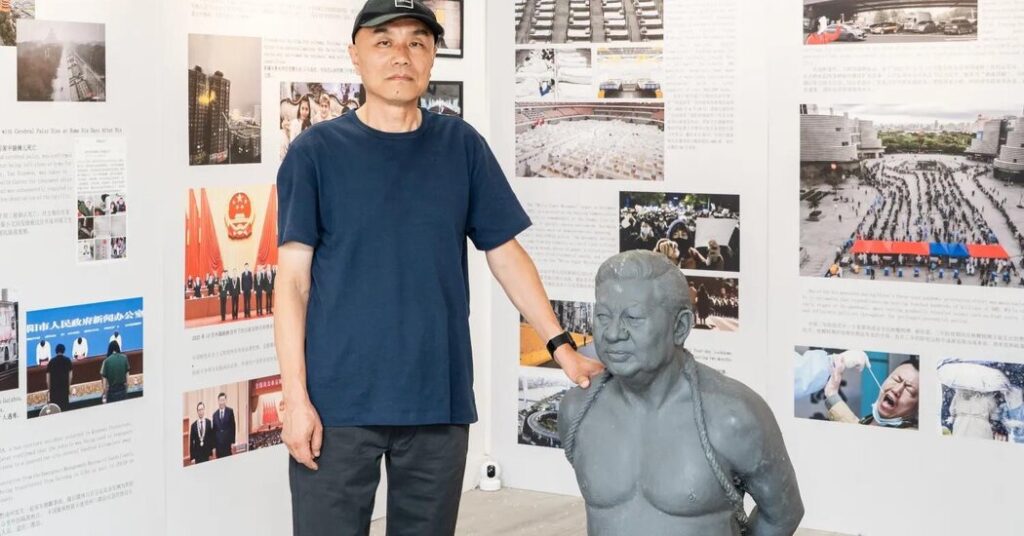

Together, they created four statues.

The statues depict Mr. Xi and the first lady, Peng Liyuan, kneeling and their hands bound behind them. In one set, they are clothed. In the other, they are bare-chested, emphasizing their humiliation.

This depiction of a disgraced, kneeling couple evokes a potent and specific Chinese historical parallel: the enduring example of Qin Hui.

He was the 12th-century official blamed for the wrongful execution of General Yue Fei, an admired national figure. A bronze statue of the official, and another of his wife, kneel in atonement outside the general’s tomb in Hangzhou, China.

Mr. Hui understood the symbolism of the statues of the Chinese president and his wife kneeling. He also understood the risks.

In November 2023, as Mr. Xi prepared to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in San Francisco, Mr. Hui was preparing his protest. He had posted on social media that he planned to display the sculptures near the summit as a silent rebuke to a government he believed had abandoned its people.

Federal prosecutors said that two men, Cui Guanghai, 44, of China, and John Miller, 64, a British national who is a permanent U.S. resident, orchestrated a harassment campaign to derail Mr. Hui’s protest. The harassment took place from October 2023 through at least April 2025, according to court documents.

Tracking devices were placed on Mr. Hui’s car. His tires were slashed to keep him from making the six-plus-hour drive with the sculptures to the conference in San Francisco.

In May, a grand jury indicted Mr. Cui and Mr. Miller on charges of conspiracy, interstate stalking and smuggling. The Justice Department called the incident part of “a blatant assault on both our national security and our democratic values.”

It was unclear from court records whether Mr. Cui and Mr. Miller had legal representation.

Mr. Hui said he had also learned that in China, police officers had taken his parents in for questioning.

A few days before the summit, his mother, who is in her 80s, called from his hometown in Liaoning, China. She was in tears, begging him not to attend the summit, he said.

For Mr. Hui, it wasn’t the first signal of trouble, but it was the clearest. “I had no other choice but to cancel my plan,” he said.

Mr. Hui was not alone in his experience.

In the Mojave Desert, Chen Weiming, a California-based sculptor from China, created a towering installation made of fiberglass that partially portrayed Mr. Xi with protruding spikes of the coronavirus on his head. It was titled “CCP Virus,” alluding to the Chinese Communist Party.

In spring 2021, vandals set it ablaze. Mr. Chen said it wasn’t the first time — or the last.

“The pressure is constant,” he said. “But the message must stand.”

Mr. Chen, 68, runs Liberty Sculpture Park in Yermo, Calif., where dozens of politically charged works are on display, including those that memorialize Tiananmen Square and denounce Hong Kong’s national security laws.

Mr. Chen said that he and his volunteers have faced repeated harassment since 2022: studio break-ins, surveillance and threats. Even collaborators — curators, filmmakers, publishers — have reported harassment, Mr. Chen said.

The attacks, he said, have only deepened his resolve.

“I had to rebuild it,” Mr. Chen said of the sculpture. “This time in steel so they can’t destroy it.”

In March 2022, federal prosecutors announced charges against three people over their involvement in a repression scheme, which included setting fire to Mr. Chen’s sculpture and spying on the artist.

Maya Wang, an associate Asia director at Human Rights Watch, said these cases underscore how far the Chinese government will go.

“The use of transnational repression demonstrates a symptom of the underlying structure of the Chinese government’s influence operations around the world,” Ms. Wang said. “It has marginalized voices critical of Beijing and elevated those who are friendly to it.”

Since 2023, Mr. Hui has lost more than 30 pounds, he said. He struggles to sleep. He keeps his phone close.

Still, Mr. Hui opened his exhibition at the Pandemic Victims Memorial Organization in Corona, Calif. The sculptures stand in place. Security cameras watch the doors.

As for continuing to commission art in protest of the government, he said: “Whether I do it or not, I will face huge risks. Therefore, I will continue.”

Mark Walker is a Times reporter who covers breaking news and culture.

The post ‘Orwellian Climate of Fear’: How China Cracks Down on Critics in the U.S. appeared first on New York Times.