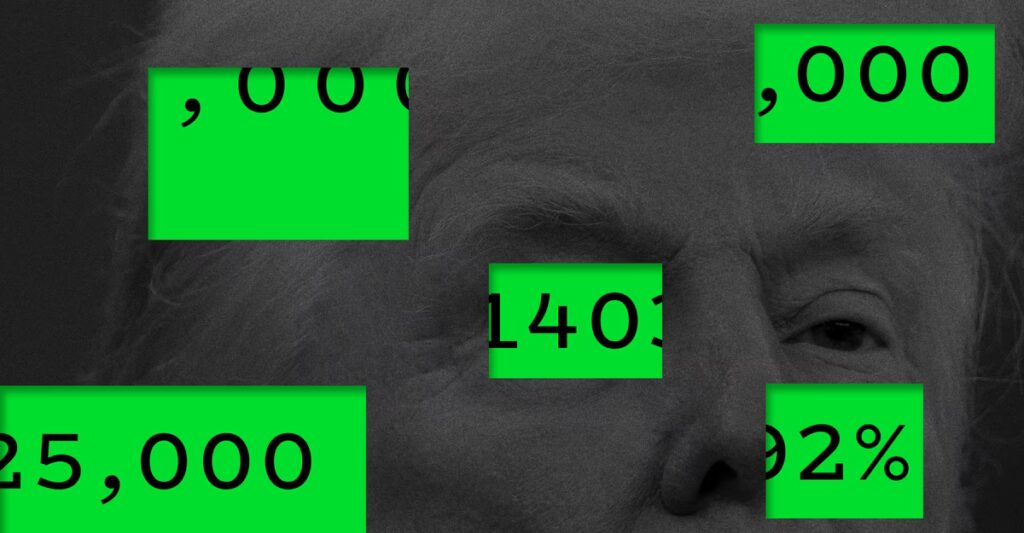

President Donald Trump likes to use a big number to anchor his point, especially when he wanders off on a tangent. Often it seems that a specific figure is on the tip of his tongue.

At this year’s ceremonial turkey pardon, Trump praised a farmer from Wayne County, North Carolina, for raising two “record-setting” birds, but then pivoted to his own electoral margin of victory: “I won that county by 92 percent.” (In fact, he won it by 16 percentage points.) At a McDonald’s corporate event last month, Trump claimed that the United States controls 92 percent of the shoreline of the Gulf of Mexico (the Gulf of America, as he calls it). It’s really about 46 percent. Trump won the veterans’ vote, he said on Veterans Day, with “about 92 percent or something,” and in July, he said he won farmers—well, “by 92 percent.” (More accurate estimates of the portion of the electorate he won would be 65 percent of veterans and 78 percent of voters in farming counties, according to exit polls and election data.)

His fixation on the number between 91 and 93 has been a feature for a while. In April, Trump claimed that egg prices had fallen by 92 percent. (The Bureau of Labor Statistics said 12.7 percent.) And at a rally shortly before last November’s election, while railing against journalists and the media, he allowed that “not all of them” are “sick people.” Just “about 92 percent.” That one, admittedly, is difficult to fact-check.

I came upon this curious pattern in the course of tracking down the basis for a far more serious claim the president has made repeatedly as part of his justification for the U.S. military buildup near Venezuela. More than two dozen strikes on small boats allegedly carrying drugs in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific have killed more than 100 people since September. The strikes have formed the core of the administration’s ongoing campaign to treat President Nicolás Maduro as a “narco-terrorist,” which many view as a veneer for wanting to see the Venezuelan strongman ousted from power and work with a new government to secure access to the country’s oil and rare earth minerals.

[Read: Trump knows what he wants, just not how to get there]

“The drugs coming in through the sea are down to—they’re down by 92 percent,” Trump told Politico on December 8. At a roundtable later the same day, he went with “92 or 94 percent.” Three days later: “Drug traffic by sea is down 92 percent,” Trump said in the Oval Office. A day after that brought a new estimate: “We knocked out 96 percent of the drugs coming in by water,” he told reporters.

More often than not, the president links the 92 (or more) percent claim to another: “Every one of those boats you see get shot down, you just saved 25,000 American lives.” In December alone, he has cited that figure—25,000 American lives saved per boat strike—on at least six different occasions.

I asked the Coast Guard—the lead federal agency for maritime drug interdiction—for any underlying data or information to support both of those figures. The Coast Guard referred me to the Pentagon. The Pentagon referred me to the White House. The Department of Homeland Security referred me to the Pentagon and the White House, which repeated Trump’s remarks without elaboration.

“President Trump is right. It is widely known that one small dose of these drugs is deadly, fentanyl is the number one killer of adults between the ages of 18 and 45, and any boat bringing this poison to our shores has the potential to kill 25,000 Americans or more,” Anna Kelly, a White House spokesperson, told me in a statement. “Rather than try to poke holes in these facts, The Atlantic should join President Trump in elevating the voices of families who have lost loved ones to the scourge of narcoterrorism.”

The president’s claims, however, are so porous that I hardly found anywhere to poke. Although Trump and other officials have repeatedly said that the goal of the strikes is to combat the trafficking of illicit fentanyl—the synthetic opioid chiefly responsible for an epidemic of fatal overdoses over the past decade—the drug does not come from South America. It enters America primarily across the border with Mexico and is produced using precursor chemicals from China. Venezuela, however, is primarily a transit country for cocaine bound for Europe.

In a briefing with lawmakers early last month, top officials acknowledged that they believed it was cocaine, not fentanyl, on the boats. A former senior Coast Guard official told me that in his more than three decades in the service, he has not been aware of a single instance of an intercepted load in the Caribbean or eastern Pacific containing fentanyl. In sum, the boats being struck aren’t carrying the drug that is the leading cause of overdose deaths in the U.S.—and what drugs they may be carrying aren’t coming to America. So it is hard to see how each strike saves 25,000 American lives.

[Read: Trump’s boat strikes could make the cartel problem worse]

Bill Baumgartner, a retired Coast Guard rear admiral who directed the agency’s operations in the Caribbean, told me that number “is just complete and pure fantasy.” The only way to arrive at that total of saved lives is if you would have rounded up 25,000 people and forced them to consume lethal doses of cocaine—a claim “just as stupid as saying that there’s a box of ammunition; if you confiscate a box of ammunition, you have saved 100 lives because there were 100 bullets there,” Baumgartner said.

It is even unclear how many of the destroyed vessels were actually carrying narcotics. The administration has not specified or released evidence of the types or quantities of drugs on them. When identifying boats ferrying drugs, “the intelligence isn’t foolproof,” and destroying a vessel with a strike—unlike boarding it during an interdiction—leaves no room to correct faulty intelligence, Baumgartner said. In the 13 months leading up to early October, 21 percent of the boats interdicted off the coast of Venezuela turned out not to be carrying any contraband, according to data shared by Coast Guard Acting Commandant Admiral Kevin Lunday in a letter to Senator Rand Paul, a Republican.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that in the 12-month period ending in April, there were about 73,690 total drug overdose deaths in the United States (although that number is likely to increase when final data are tallied). If it were the case that each strike since September has saved 25,000 American lives, and given that 28 boats have been destroyed to date, the operation would have saved 700,000 lives—more than nine times the total U.S. drug overdose deaths in a year. “That makes no sense,” Adam Isacson, an expert on drug trafficking in Latin America at WOLA, an NGO based in Washington, D.C., told me.

The majority of overdose fatalities stem from opioids, not stimulants such as cocaine. In 2023, the most recent year for which such data are available, the CDC tracked 29,449 cocaine-linked deaths. (About 1.2 grams of cocaine can constitute a fatal dose. That amount is 600 times greater than the 2 milligrams of fentanyl that can cause a deadly overdose.) But notably, nearly 70 percent of cocaine- and other stimulant-related deaths that year also involved fentanyl.

As for the basis for the president’s claim of a 92 percent decline in maritime drug traffic: “We’ve only seen that in Trump’s remarks. No sourcing, no other data,” according to Isacson. (The White House did not specifically respond to my inquiry about it.) But the numbers the government does release give ample reason to doubt the statistic. Last month, the Coast Guard touted a record-setting year of drug interdiction; the agency seized more than 510,000 pounds of cocaine, primarily in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific, compared with the 167,000 pounds it seized on average in prior years. This month, as part of its ongoing maritime-law-enforcement operations separate from the strikes, the Coast Guard seized 20,000 pounds of cocaine in a single interdiction. But global cocaine supply and demand continue to reach new heights, according to a June report from the United Nations. And counternarcotics-enforcement veterans told me that even if drug traffic by sea has seen a sharp drop, that does not signal an overall decline in cocaine traffic, because traffickers adapt and reroute shipments.

Perhaps the president has divined these numbers through a mathematically rigorous process beyond the reaches of my imagination. After all, Susie Wiles, the White House chief of staff, told Vanity Fair that her boss is a “statistical savant.” More likely, his affinity for 92 percent and extravagantly large round numbers is what in a game of poker might be called a tell. In 2019, Bloomberg noticed 10,000 cropping up whenever Trump made big claims, in topics such as the stock market and ISIS fighters. It was the number Trump cited for known or suspected gang members whom ICE removed in 2018 (though the agency put that number at 5,872). And it’s the number of points he said the Dow Jones would have been up in 2019 had the Federal Reserve not raised interest rates the previous year.

Not every time the president cites a 92 percent is off base. His August boast of a “92 percent” approval rating for the Department of Veterans Affairs, for instance, was actually slightly less than the 92.8 percent of veterans who reported trusting the VA for their health care in the agency’s survey that month. That was up from—wait for it—92 percent under the Biden administration the previous year. But more often than not, the number seems to serve as a clue that the commander in chief might be reaching for a number he can easily remember, caring little whether it is accurate.

At three different rallies in the fall of 2024 leading up to Election Day, Trump bragged about his nearly decade-long campaign to denigrate the press. “The fake news back there—they were at 92 percent approval rating when we started this journey in 2015. And now they’re less than Congress,” he said on November 2. “I’m very proud of that.” In fact, the year the president descended his golden escalator and upended the country’s political life, Americans’ trust in the media was not at 92 percent. Unfortunately for us, it stood at a then-historic low of 40 percent. In the years since, it has dropped to a new historic low of 28 percent. Congress’s approval, for the record, stands at 15 percent.

The post Trump’s Favorite Number Is… appeared first on The Atlantic.