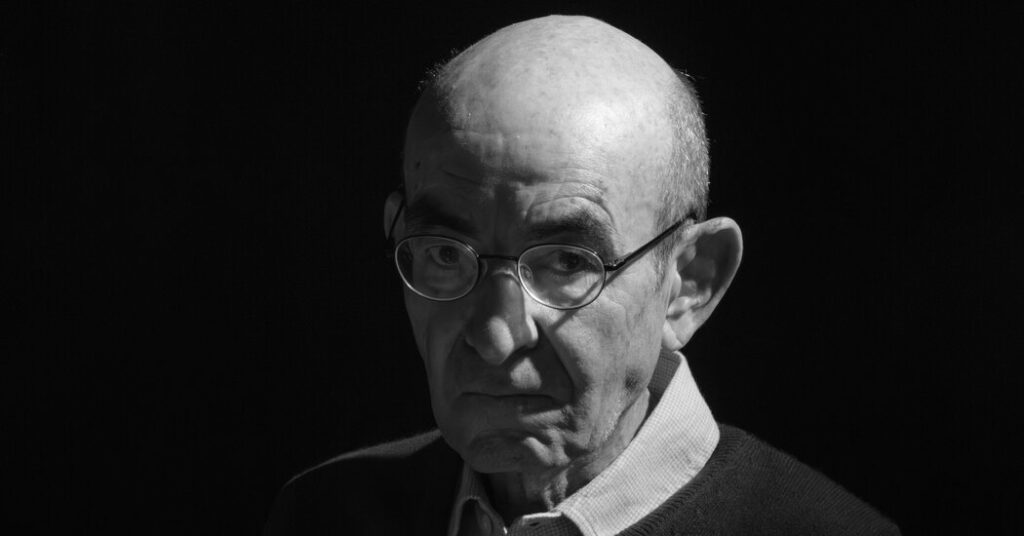

The writer, lawyer and human rights activist Raja Shehadeh, who is 74, has spent most of his life living in Ramallah, a city in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. This is where his Palestinian Christian family ended up after fleeing Jaffa, now part of greater Tel Aviv, in 1948, as Jewish paramilitary forces bombed the city. Since he was a much younger man, Shehadeh has been doggedly documenting the experience of living under Israeli occupation — recording what has been lost and what remains.

That work, defined by precise description and delicately deployed emotion, has won him widespread acclaim. Shehadeh’s 2007 book, “Palestinian Walks: Forays Into a Vanishing Landscape,” won Britain’s Orwell Prize for political writing. Here in the United States, his book “We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I” was a finalist for the 2023 National Book Award. He’s also a co-founder of Al-Haq, a human rights organization — recently sanctioned by the United States government — that has documented abuses against Palestinians in the occupied territories for over 45 years.

To read Shehadeh’s work — including his essays for The Times’s Opinion section — is to be exposed to a thinker with a long and stubbornly optimistic view of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This is a man who believes that peace remains possible. But he also maintains that for peace to have any chance of prevailing, there’s so much — the stories told about the region, even the basic facts — that needs to be fundamentally reconsidered.

At the end of another brutal year of strife and suffering, with a cease-fire between Israel and Hamas holding but a plan for what’s next still unclear, I thought it might be useful to speak with a writer who has a firsthand sense of the ways in which the past need not portend the future — and the ways in which it should.

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Amazon | iHeart

The pursuit of justice is one of the great themes of your work. Given that politics based in raw power are so ascendant now, what is the role of a justice-driven writer? The first thing is to document, make the situation clear and avoid mystification. Colonization works by mystifying, by making people lose a sense of who they are and how they got to the point that they got to. The people who are younger than me never knew the land as it was before, never knew what the hills looked like before the settlements were built all over them, never knew the roads before they were distorted and full of checkpoints. So one of the objects of my writing has been to describe the landscape as it was before. Then also, they might not be aware of how we got into the legal situation that we are in now. It’s important to remove the mystery and explain that it was a slow process, which was deliberate.

When you talk about the process, you’re specifically referring to the building of settlements in the West Bank? That’s a big part of it. Other parts are how the present generation of Palestinians have never met an Israeli who is not a settler or a soldier. There were times when Israelis came over to Ramallah and to other places in the West Bank and Gaza, and went to restaurants and had businesses with Palestinians. There was interaction on many levels. Now none of this is possible because of the apartheid wall, and because of the checkpoints. Many Palestinians have never been to Jerusalem from Ramallah, which is 15 kilometers away, and never met a normal Israeli civilian. So they have a distorted picture of what Israelis are. And likewise, the Israelis of the Palestinians.

This connects to an illusion that I think is pervasive: the illusion of collective responsibility; the illusion that all Israelis are in some way responsible for the actions of Netanyahu’s government or the I.D.F., or the illusion that all Palestinians are supporters of Hamas or might be terrorists. What might we do with that illusion? The illusion is very dangerous, because it led to the genocide in Gaza. The Israelis became convinced, because their leaders said that all the Palestinians are responsible for the murders that took place on Oct. 7. So they went about killing civilians without thinking about it. Likewise, in the West Bank. I used to be able to speak to the settlers or to the army and ask them, Why are they doing this? And now it’s impossible. Now they would shoot. So it’s very dangerous, this illusion. It’s the leaders who indoctrinate their people that this is the case, and that’s where the problem comes.

How might we break the illusion? Start teaching about the other, teaching the literature of the other, teaching that there were times in Palestine when the Jews and the Arabs lived together amicably and peacefully, and they were important times. They could concentrate on these issues rather than concentrate on the massacres that took place, which were not so frequent. They did take place. But rather than concentrate on these, concentrate on the brighter spots. But that means that the state would have to be pursuing peaceful resolution. That’s not the case now.

People can often conceive of the conflict as being thousands of years old, when the reality is it’s a little over 100 years old. And there’s a long history of what you just described: a different kind of living in that region than is often assumed to be the case. That’s absolutely true. Palestine has always been a place for three religions, and the three religions lived side by side and enriched life, because it’s enriching to have the differences. And now one religion is trying to dominate and say it’s the only one that is going to be allowed in that land, and that’s perverse.

What you’re describing is Zionism. Can you talk about your personal experience of Zionism as a political project? Zionism has made my life impossible. First they tried to create a state in ’48 and forced people in Palestine to leave, and they didn’t allow them to return. Then in ’67, they continued with the policy of trying to build settlements and encourage people to leave. [The Israeli right-wing politician] Rehavam Ze’evi called it a “negative magnet” — that they will make life so difficult for us in the West Bank that we will leave. So our life has been complicated by the Zionist aim of emptying Palestine of Palestinians. We are subject to so many rules and regulations that make life rather impossible. But people have persisted in staying and refused to leave, and I think that’s been the most important tactic and strategy. Much more important than armed resistance, because armed resistance only causes more arms, which Israel has.

There is a lot of debate about the extent to which Zionism and Judaism are intertwined, which ends up getting into questions of whether criticism of Zionism is de facto antisemitic. My sense is that it’s not that difficult for you to separate the political project of Zionism from feelings about the Jewish people. I’ve never had that problem, because I’ve always felt that Jews are just members of a religion and it has nothing negative about it and nothing in enmity with me. But Zionism, which is trying to use the religion to promote a certain political project, is an enemy to me. The two are separate in my mind entirely. I find it very strange when people say that criticism of Zionism is antisemitic. I understand that it’s a political device in order to scare people into not attacking Zionism and calling them antisemitic if they do.

You’ve written at length about your friendship with a Jewish Israeli, Henry Abramovitch. Are there aspects of your friendship with Henry that might serve as a model for larger groups of people in their political relationships? I have several very good friends among Israelis, and their friendship is very important to me. The important thing is openness and clarity and attention to the suffering of the other. So I would not accept somebody as a friend who doesn’t understand that the right of return is a right that should be upheld. Because to deny that the Palestinians exist is so profound and painful that a friendship based on a denial of that would not be a good friendship and would not endure.

When have your friendships with Jewish Israelis been most severely tested? With the genocide, it’s a very big challenge, because I expect the Israeli friend to speak out and condemn and be attentive to my suffering as a Palestinian, seeing that part of my people are being murdered wholesale in Gaza.

In your book “What Does Israel Fear From Palestine?” you wrote about a conversation you had with an Israeli friend. You wrote: “Every time I mentioned an atrocity committed against Palestinian civilians by the Israeli Army in Gaza, he brought up a criminal act committed by Hamas on Oct. 7. Then with a sad voice he assured me that the Israelis are suffering from trauma and are grieving.” It’s completely understandable to me that people have a strong desire, maybe even a need, to have their suffering recognized. But is there a way to address that need on both sides without invoking an unproductive, endless competition of suffering? Yes, I think that is true, because also the suffering at the time of the Holocaust is always used as We have suffered most, and nobody can suffer as much. Every suffering is a suffering, and it shouldn’t be underestimated. But to use that as a justification for causing more suffering is untenable, wrong, immoral. That is why when this friend was justifying what was happening in Gaza because of trauma, I did not accept it. I thought it was very disappointing. But there’s a lot of it in Israel, and there’s this double consciousness of knowing and not knowing.

Can you tell me more about that double consciousness? Well, on the one hand, they know what they’re doing in Gaza, and on the other hand, they’re blocking it and pretending not to know. That’s how they can live with themselves: by blocking the knowledge that is there, that they cannot deny, that is obvious, that the whole world knows about. It’s the same with the refugees. They knew about the fact that they threw out the Palestinians from their homes [in 1948] and yet didn’t really know it and didn’t accept it. They blocked it. That was why they were able to live in the houses of the Palestinians who left and not feel guilt.

The writer Edward Said famously wrote that Palestinians lack the permission to narrate. Is that still the case? There has been almost a revolutionary change since the Gaza genocide. The Palestinians now are much more able to tell their story. I think Edward was referring to the fact that they could not speak about the Nakba at that time. Now it’s possible to speak about Nakba, and the word Nakba has become well known, and you don’t even have to explain what it is. There has been an opening to writers and filmmakers and playwrights to create works of art and literature and be published by establishment press and be distributed by those who in the past refused to distribute Palestinian literature. So there has been a big change and much more knowledge about the Palestinians and much more openness to listen to the Palestinians.

There have been calls from Palestinians and advocates of the Palestinian cause to boycott The New York Times and other publications because of their coverage of the conflict in Gaza. But for you, how and why do you decide to engage with the media? I think that the criticism about The Times is right, because The Times has not been very forthright in calling the genocide a genocide and giving full coverage to the Palestinians, although this has changed in recent weeks and months. So there has been a change, and we should always work for change rather than give up, because The Times is a very important newspaper and has many important readers. So it’s important to keep the lines open and to try and bring it into more sympathy and understanding of the Palestinians. This is an ongoing issue, because it can be changed and then revert back to the old ways. It’s an ongoing battle.

In November 2023 you wrote a piece for The New York Review of Books in which you described having two plumbers come to your home in Ramallah the morning of Oct. 7 and seeing the younger one looking at videos on his phone and smiling about what Hamas was posting. The idea of someone feeling pleasure about that day is horrifying to a lot of people. How did you understand expressions of happiness about what happened on Oct. 7? Well, it was immediately after it happened, so we didn’t have much information except what was being streamed live of breaking the barrier. The idea that the people of Gaza who had been imprisoned for years were able to break the barrier was something that brought great happiness to this young man. At that point we did not know all the details of what was happening, so I understood his happiness because of the bravery and the fact that it was possible to break through the barrier. Later on, when I realized what had happened and some of the crimes that were committed, it was a different feeling that I had, of course.

“Bravery” is a word that you used in a way that was interesting to me in your book “Language of War, Language of Peace,” written in the aftermath of the 2014 Gaza War. In that book you referred to the bravery of the Hamas fighters who are standing up to the mighty Israeli Army. Bravery is widely understood to be a positive attribute, so how do you reconcile the bravery that you saw with the fact of Hamas’s violent religious extremism and total lack of regard for human rights, even in Gaza? The fact that Hamas was making attempts at fighting back against the Israelis is a legitimate thing, because international law allows the occupied people to fight and struggle against the occupation, and they were struggling against a power that is much, much stronger than they are. And yet Hamas, of course, is not very responsive to human rights at times. That is something to be condemned. So the attempt at taking a stand against Israel is legitimate, but the excesses are not acceptable to me.

I realize I’m asking you to speak on behalf of Palestinians broadly. Do you find that to be a difficult position to be put in? I’ve always felt that I’m not representative of the Palestinians. I’m too individualistic and too single-minded. I speak my mind and my feelings and opinions, and even if they are unpopular, I would rather not change them. So if I’m asked to condemn one side or the other, I refuse, because I think condemning is such a useless thing. Who am I to condemn, and what is the effect of my condemnation? Very often, with a Palestinian, you have to start by making sure that the Palestinian condemns certain things before we can go any further. And I think that is a very unfortunate attitude.

But surely your work is a condemnation of Israeli conduct? Well, yes, in a sense it is, but it’s an attempt to not stop at condemning the Israeli conduct but explain it, and explain it with a view of getting it changed and getting us out of this conflict that we are in.

Are there things that you say that you find are controversial among Palestinians? There are many Palestinians who are thinking in terms of one state. I’d like one state, but I’m not sure that we are ready for one state. I prefer that first [comes] the ending of occupation, and then we work out how we want to live together with the other side. It has to be a slow process. And that’s not very popular among many Palestinians now.

What do you think the endgame is for the Netanyahu government in the West Bank and Gaza? If they continue as they are now, fighting wars on so many fronts and thinking that only by fighting wars and by strength can they survive, they will end up in a very bad state. It will be the end of Zionism, and perhaps Israel will become a pariah state and totally undemocratic and its future will be in peril. You cannot keep on fighting wars and think that through fighting wars, you will survive. Also, the assumption that the United States will continuously support them to the extent that they are now is beginning to be questionable. And without the support of the United States, their possibilities for fighting wars and winning wars is much less. I think Israel is going in a very difficult and bad direction.

Earlier, you used words like “apartheid” and “genocide.” These are highly contested terms. Sometimes I wonder if the impulse to debate those terms can risk turning arguments about the conflict into arguments about semantics. Are there downsides to using those terms, or maybe the contentiousness is why you feel you need to use them? I’ve been following the Israeli development of the apartheid regime in the West Bank since 1979, so I’m very familiar with how it came about. I didn’t use the term “apartheid,” because I didn’t want to alienate the readers and do exactly what you’re saying: focus on the term rather than on the facts. But now that it has become very clear that the situation is one of apartheid, I think it’s very important to use the term. And likewise with “genocide.” I didn’t use genocide until I became very clear that the definition of genocide exactly fits the case in Gaza, and then I thought it’s important to use the term because it has legal consequences, which I would like to see take place.

What are some of those legal consequences? Well, it’s a crime, and those who perpetrated the crime should be punished. That’s very important, because otherwise they will repeat the same action. And in a way, because nothing has happened to Israelis who advocated genocide in Gaza, they’re repeating similar tactics in the West Bank every day. So it goes on and on and on. The only way to stop it is by taking legal action against them.

After Oct. 7, the anti-Zionist Jewish writer Peter Beinart wrote a piece for The New York Times Opinion section arguing that “when Palestinians resist their oppression in ethical ways — by calling for boycotts, sanctions and the application of international law — the United States and its allies work to ensure that those efforts fail, which convinces many Palestinians that ethical resistance doesn’t work, which empowers Hamas.” Does that diagnosis ring true for you? Absolutely. And the best example is the case of sanctioning Al-Haq, which is an organization I started 40 years ago. Trump’s government has sanctioned the organization and rendered it difficult to function. It cannot have access to its email, it cannot have funding, it cannot go on with its normal activities, the videos that document violations of Israeli actions have been removed from YouTube. So people will say, What’s the use of human rights when this is the treatment? When people have no protection against Israeli brutality by the army or the settlers, then they say, What’s the use of being nonviolent when violence is committed against us? Then the answer is, the only way is to fight like Hamas, and that’s what young people have come to conclude.

When Secretary of State Marco Rubio released a statement announcing the sanctions against Al-Haq, the justification he gave was that Al-Haq has “directly engaged in efforts by the International Criminal Court (I.C.C.) to investigate, arrest, detain or prosecute Israeli nationals, without Israel’s consent.” Is that correct? Al-Haq has been involved in helping the investigation by the I.C.C. of Israeli crimes, and that is something that we have been hoping for all along — that it will come to a point when we can take the case to the highest court in the world. So we gladly support that investigation. To be sanctioned because of our attempt at going into a court of law is very strange and very problematic for a country like the United States, which proposes to be a country for the rule of law and for human rights.

Something that has struck me in talking to you is a calm or lack of stridency in how you make your arguments, which seems very different than the stridency of younger pro-Palestinian activists. I’m curious if you see generational differences in how pro-Palestinian voices express themselves and the tactics that they call for? Yes, but I think that even when I was young I always had a mild tone.

So it’s you, not generational? I always try to understand the other side because I want to be effective and speak to the other side in a language that they can understand. I’ve always been hesitant to use strident language and to be extremist in order to win over the other side. That has been my effort all along — to win the other side — but it has never worked.

Does that give you pause about the efficacy of your tactics? No. I’m going to continue on the same track, because I think it is important to realize that we have two nations living on one small strip of land. Eventually they have to live together. And unless we try to make the other feel the humanity of each of us — they of us and we of them — then we cannot survive.

We’re speaking right at the end of the year. What is your wish for the new year? I would like the end of the Gaza siege. If the siege ends and people are able to visit Gaza, especially Israelis, and see what has been done to Gaza, then it might awaken the Israeli people to the crime that they’ve committed. That could be very hopeful. Also it gives a chance for the Gazan people to to live again, to import the machinery they need to rebuild Gaza, which they are not able to do now, and it will end their suffering that has been going on for 18 years. It’s too much. Too much. And so this is my hope for the new year. It’s not a small thing — it’s a big thing — but it’s my hope.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations. Listen to and follow “The Interview” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, iHeartRadio or Amazon Music

Director of photography (video): Benjamin Breading

David Marchese is a writer and co-host of The Interview, a regular series featuring influential people across culture, politics, business, sports and beyond.

The post Raja Shehadeh Believes Israelis and Palestinians Can Still Find Peace appeared first on New York Times.