On President Trump’s first day back in office, Representative Mikie Sherrill, a Democrat from New Jersey, hit him with a new political mantra. His barrage of executive orders, she argued, had failed to make any attempt to address the “affordability crisis.”

It was an early sign of where the Democratic Party was headed. Nearly a year later, Ms. Sherrill is preparing to take office after winning her bid for governor. And “affordability” is dominating the political conversation.

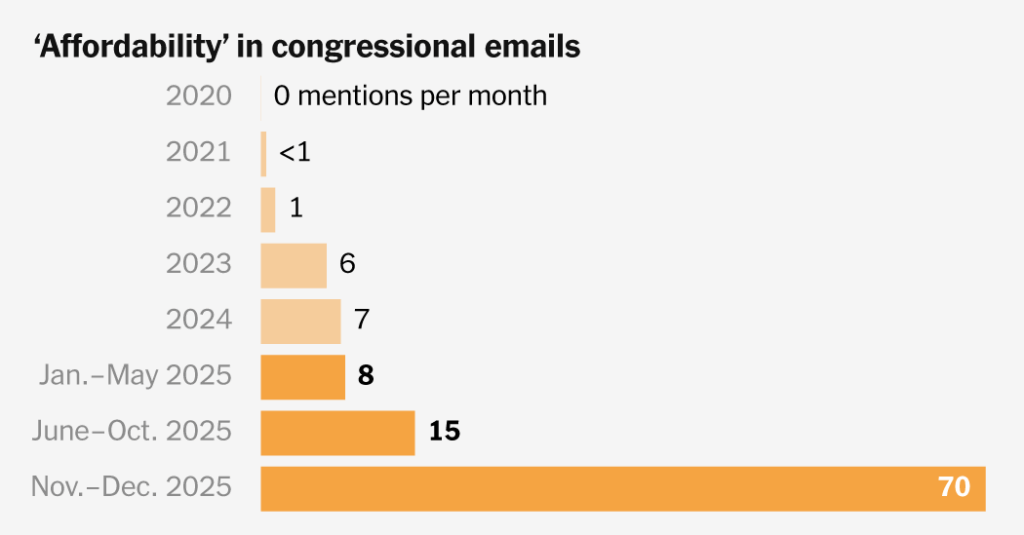

The word has long been used sporadically in politics — Mr. Trump promised to “make America affordable again” during his 2024 campaign — but never with the same force and frequency as in the past few months.

Democrats used “affordability” to harness worries about the cost of living and sweep to victory in this November’s elections. And once that happened, references to “affordability” as a stand-alone term skyrocketed.

Now both parties are preparing for affordability — a useful shorthand that nods to the costs of housing, child care, groceries, health care, utilities and other essential expenses — to play a major role in the midterm elections next year. Survey after survey has shown that Americans rank economic concerns as their top issue and increasingly worry they are falling behind financially.

That has left Republicans playing catch-up. Even as Mr. Trump contends that the word is a “hoax” and a “con job,” he is traveling the country on an “affordability tour” to reassure voters. The Biden administration was “when we first began hearing the word affordability,” Mr. Trump said in his recent televised address.

So far, the efforts haven’t worked: Approval of his handling of the economy has been falling for months.

“Affordability” emerged quickly enough to catch even some Democratic veterans off guard. James Carville, the Democratic strategist who coined his own enduring catchphrase in 1992 with “it’s the economy, stupid,” said he hadn’t yet totally made the pivot from “cost of living” to “affordability.”

“One day, I never heard the word, and the next day I heard the word a hundred times,” he said. “It all happened so fast.”

How it happened so fast

Over the past decade, Democrats have tried many phrases while attacking Mr. Trump on economic issues. The progressive wing of the party decried “economic inequality” and campaigned on “economic fairness” for the most vulnerable Americans. Moderates talked about bolstering the middle class and restoring “an economy that works for everyone.”

President Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s administration was focused on tackling inflation, even naming the signature piece of economic legislation passed during his term the “Inflation Reduction Act.”

Affordability resonated in a way that other terms failed, say strategists, politicians and political scientists, because it echoes how voters think about their personal budgets — rather than the more abstract academic language of economics, activism and policy.

In focus groups, Democrats say they often heard participants talk about their inability to afford what were once considered the expectations of a middle-class American life: college tuition, buying a home, retirement. Increases in prices for essential goods and services — groceries, rent, child care and utilities — stretched budgets beyond comfort for some voters.

“The way people think about it is they have the same amount of money and everything costs more and they are drowning,” said Neera Tanden, who served in the White House in the Clinton, Obama and Biden administrations and now leads the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank. “They can’t afford to live the way they used to live.”

The recent success of the Democrats’ message is rooted in their previous failure to understand the economic mood of the nation.

In the summer of 2023, the Biden administration announced a re-election run on the virtues of “Bidenomics” — an effort to reclaim a derisive term for Mr. Biden’s economic policies used by his Republican opponents. As part of the effort, he traveled the country boasting about saving the economy from a recession.

Voters didn’t buy it: His approval rating on the economy plunged.

“It’s very hard to convince people that their reality is not the reality that they’re actually in,” said Lindsey Cormack, a professor of political science at Stevens Institute of Technology.

The tone-deaf messaging quietly infuriated Democrats across the party. When former Vice President Kamala Harris became the nominee, she initially focused on proposals that would have a direct impact on costs, like a tax credit for newborns and down payment assistance for first-time home buyers.

But in the final weeks of her campaign, she pivoted to a message focused more on attacking Mr. Trump as a fascist who would destroy the country’s democratic foundations.

Some Democratic officials, politicians and strategists warned that her focus on Mr. Trump’s character was a political error. Future Forward, the leading pro-Harris super PAC, had spent $700 million testing messages and ads and found that voters overwhelmingly ranked lowering the cost of living as their top priority.

“Voters do see Trump as a threat to democracy,” the group wrote in a private research memo in late October. But, it said, “this threat is superseded by economic concerns that make choosing him appealing.”

After Ms. Harris lost, many Democrats blamed a failure to listen to the concerns of voters. In the earliest days of the Trump administration, some prominent Democrats attempted to refocus their party on cost of living issues.

Representative Hakeem Jeffries, the Democratic leader, opened the new Republican-controlled Congress with a speech on the House floor that rattled through a list of basic expenses that he said had gotten too high. “We need to build an affordable economy,” he said.

Ms. Sherrill, in particular, had been frustrated by the Biden administration’s economic messaging. When voters raised cost of living concerns, she complained to aides, the White House would respond by rattling off statistics.

She announced her campaign for governor two weeks after Mr. Trump’s victory with a promise to “make life more affordable.” In March, she released an “Affordability Agenda,” with policies focused on lowering the costs of housing, utilities, child care, prescription drugs and groceries.

Representative Abigail Spanberger, a Democrat who was running for governor of Virginia, followed with her own “Affordable Virginia Plan.” And in New York City, Zohran Mamdani began a sharp rise in the polls with the campaign slogan of “a city we can afford” and policies that promised to tackle the costs of food, public transit, child care and housing.

Angela Kuefler, a Democratic pollster who conducted surveys for Ms. Spanberger and Ms. Sherrill, said neither campaign asked voters for their views on the word “affordability.” But they heard a “level of panic and urgency” about affording basic costs.

“There was never something special about that word,” she said. “It just speaks to the literal crisis people are feeling.”

An opening on tariffs

In Washington, national Democrats were seeing voters begin to shift the blame for higher costs from the previous administration to the new one — especially after Mr. Trump announced sweeping hikes in tariffs in April.

In surveys and focus groups, Democrats said, voters connected tariffs to rising costs. An A.P.-NORC poll that month found nearly 80 percent of voters — including a majority of Republicans — expected tariffs to lead to higher prices.

Throughout his campaign, Mr. Trump had promised to bring down costs on “Day 1” of his administration. Now, he defended his new policy by telling Americans to buy less, including fewer dolls for their children.

“He gave everyone a reason to blame him for why costs are high,” Ms. Tanden said. “That’s the fundamental error.”

Inflation has cooled significantly since its peak in 2022, but consumers are still reeling from the cumulative effect of nearly five years of unusually rapid price increases. Prices have risen about 25 percent over that time, and inflation is still running hotter than before the pandemic.

Mr. Trump’s tariffs have not caused the broad spike in prices that some forecasters feared. But they have driven up costs for specific items, like coffee and furniture, and have kept overall inflation higher than it would otherwise have been.

And Mr. Trump has done little to address the longer-run cost of living challenges that have contributed to the sense among many Americans that the economy is not working for them — a belief that long predates the pandemic and subsequent inflation.

In the spring, the Democratic campaign committees began encouraging their candidates to make higher prices their defining issue.

Then Mr. Mamdani capped his rise by winning New York’s Democratic primary. In his speech on election night, he attributed his victory to his laser focus on costs of living.

“We have won this campaign with the vision of a city that every New Yorker could afford,” he said.

The sweeping — and broadly unpopular — domestic policy bill that Mr. Trump muscled through Congress 10 days later handed another opportunity to Democrats. Under the law, health care costs are set to rise substantially for more than 20 million Americans enrolled in Obamacare.

Surging to November

Over the summer, affordability became the central political message of the Democratic Party. Unlike its previous economic slogans, the new rallying cry reached across lines of class, geography, race and gender.

As the scope of Mr. Mamdani’s primary victory demonstrated, by focusing on “affordability,” the party could target parents struggling to afford child care, college graduates unable to buy a home and working-class voters worried about increasing Obamacare premiums.

“The cost of living and the stress on the American dream is the No. 1 galvanizing issue,” said Senator Elissa Slotkin, Democrat of Michigan, in an interview during the fall campaign.

At rallies in the final days of the campaign, former President Barack Obama made the Democratic argument clear. Voters who cast ballots for Mr. Trump, he told a crowd in Newark, “were, understandably, frustrated” with rising prices of various kinds.

“Nine months later, you’ve got to ask yourself, has any of that gotten better?” he said.

Election night provided ample evidence that voters thought not.

Ms. Spanberger and Ms. Sherrill beat political expectations, winning their contests by double-digit margins. Mr. Mamdani almost won by 10 percentage points in the highest-turnout mayoral election in New York City in decades.

As the results rolled in, Pete Buttigieg, a Democratic presidential candidate in 2020 and Mr. Biden’s transportation secretary, said in an interview that the focus on economic issues had begun to repair his party’s brand.

“Our message has to be focused on the questions that are closest to the hearts of the voters,” he said. “What you’re seeing with successful candidates on the Democratic side in these races is whatever their exact prescription is, they have been very, very focused on cost of living.”

Mr. Buttigieg quickly revised that last thought with one more word.

“Affordability,” he added.

Ben Casselman and Ruth Igielnik contributed reporting. Eve Washington contributed research.

Lisa Lerer is a national political reporter for The Times, based in New York. She has covered American politics for nearly two decades.

The post How Democrats Used One Word to Turn the Tide Against Trump appeared first on New York Times.