MADISON, Wis. — Toshiko Takaezu worked with not just her hands but her entire body. She really had to: A lot of her glazed ceramic sculptures were enormous — as tall as she and too large to wrap her arms around. Footageof her at a potter’s wheel shows her leg flapping in a funky in-and-out movement to keep the wheel spinning, as arms, hands and fingers magic the shapes into being.

In her loose, limber way, Takaezu was one of the great artists of the second half of the 20th century — a prolific modernist with a feeling for the poetry of natural materials, working at the same level as peers such as Mark Rothko, Isamu Noguchi, Sheila Hicks and Joan Mitchell.

Right now, she is the subject of a magnificent traveling retrospective, the first in 20 years, at the University of Wisconsin at Madison’s Chazen Museum of Art. (It will travel to Honolulu in early 2026.)

Takaezu found clay beautiful, she said, because “you can forget yourself in the clay, and be in tune with it.” If it sounds like something someone might say about hitting a tennis ball, playing in a band or lovemaking, you’re not confusing distinct phenomena. Rather, this is precisely how all the best things work. It’s about touch and timing, about inner and outer space coming into alignment. When it works, you forget yourself. You’re in tune with things.

Takaezu even claimed to hear music occasionally as she worked. “When I first heard it, it was kind of a shock,” she once said. She tried to hear the music again, but “when you try, you don’t [hear it]. When you let things happen, naturally it does work.”

In their beautiful display at the Chazen, curators Kate Wiener, of the Noguchi Museum, and Glenn Adamson have combined Takaezu’s ceramics with her weavings and acrylic paintings, sometimes in installations inspired by their first public presentations. The effect is entrancing. You wander around the space like a child roaming among coastal rock pools.

Takaezu was born in Pepeekeo, Hawaii, to a Japanese emigrant family. She made her first foray into ceramics in 1940, at a commercial studio in Honolulu, and went on to study first painting at the Honolulu Academy of Arts and then ceramics at the University of Hawaii (1945-1947).

She found her voice after moving to the mainland and enrolling at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. Often referred to as a “cradle of American modernism,” the school’s unified view of art and design put it near the center of the American Arts and Crafts movement.

The campus was designed by the Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen (the father of Eero), who developed the school’s curriculum and served as its first president. Saarinen and his wife, Loja, who ran the textiles department, turned Cranbrook into an incubator for a species of creativity rooted both in experiment and domesticity.

Takaezu studied there with another Finn, the ceramicist Maija Grotell, who emphasized free, individual expression over inherited technique — although the two things were by no means mutually exclusive. In 1955, Takaezu traveled to Japan, a nation then in the throes of a massive cultural reorientation. She spent eight months simultaneously imbibing avant-garde energies and immersing herself in traditional aesthetic philosophies, as expressed in, for example, the tea ceremony.

Zen Buddhism informed Takaezu’s delicately asymmetrical forms and her glazes — sometimes described as “color clouds” — suggest the spontaneity of Zen brushstrokes. They also resonate with a similar emphasis on intuitive gesture in the paintings of her abstract expressionist contemporaries — artists such as Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell.

But Takaezu’s fluid brushstrokes — sometimes in rich, earthy colors but often in turquoise, yellow, mulberry or electric blue — seem equally redolent of the landscapes, skies and flora of Hawaii.

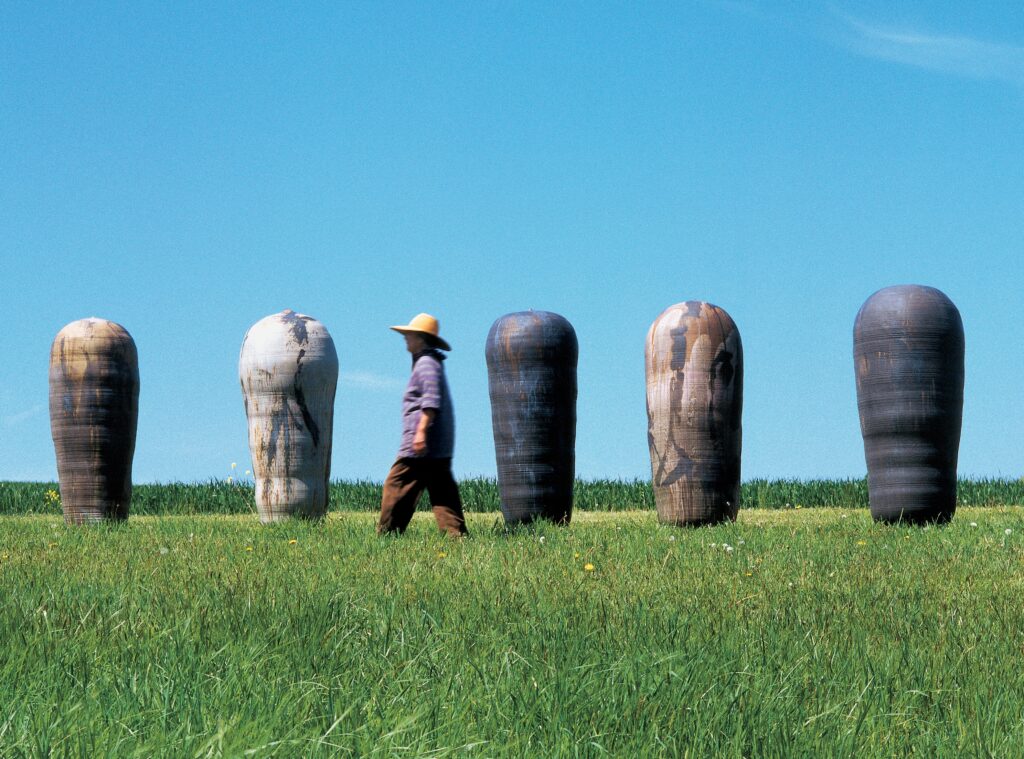

Many are spherical, sealed at the top with a nipple-like pinch. Some are small, inviting the hand to cradle them. Others are enormous, and some are suspended in giant hammocks — a typically innovative approach to display, first adopted in 1979, that grew out of her search for a solution to a practical challenge: how to dry the works away from the ground.

One series of these rounded ceramics suggests a sequence of moons, presented not as distant disks reflecting uniform light from the sun but as weighty, craggy spheres, ridged, scarred and richly colored in cosmic symphonies of rust, milk, mauve and black.

Takaezu sometimes placed small beads of clay inside her closed forms before firing them. The result was that “when shaken or moved,” as her friend Ben Watkins, the former director of Boston’s Society of Arts and Crafts, wrote, “they rustle, tinkle, clang or clunk in keeping with their personalities as individual pots.”

Many of Takaezu’s other closed ceramics are tall and slender. Some resemble giant capsules or peanut shells, created by joining two pots end to end. Always, it’s the glazes — their rich but subtle colors, and the way they blend with the natural textures and marks of the fired clay — that catch and hold the eye.

At the Chazen Museum, these works are set off beautifully by a selection of Takaezu’s vivid, high-pile textiles. The collusion of unusual textures and colors triggers reverie.

Meanwhile, her forceful abstract paintings nearby remind you that she treated the surfaces of her ceramics as if they were canvases, only in three dimensions.

Takaezu, who died in 2011, taught at several prestigious institutions, including the Cleveland Institute of Art and Princeton University. But her first position, a one-year appointment in 1954, was at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, and she returned to teach there for another spell in 1959.

She saw teaching as inseparable from making. Her ardent wish was for her students “to be able to catch on without being told.”

“To catch on without being told”: Takaezu knew that this enviable ability is available only when the body and mind come into alignment — when, as she said, we can forget ourselves “in the clay and be in tune with it.”

In these cerebral, disembodied times, we talk a lot about the power of the mind. But as the great philosopher of the imagination Gaston Bachelard wrote: “The hand has its dreams too, and its own hypotheses.” More even than the mind, it “helps us to come to know matter in its secret inward parts.”

Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within Through Tuesday at the Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin at Madison. The show will travel to the Honolulu Museum of Art from Feb. 13 through July 26.

The post A great artist of the 20th century shows how to lose yourself in work appeared first on Washington Post.