It is becoming increasingly clear that Donald Trump and his most ardent supporters view the U.S. presidency as a golden opportunity for branding.

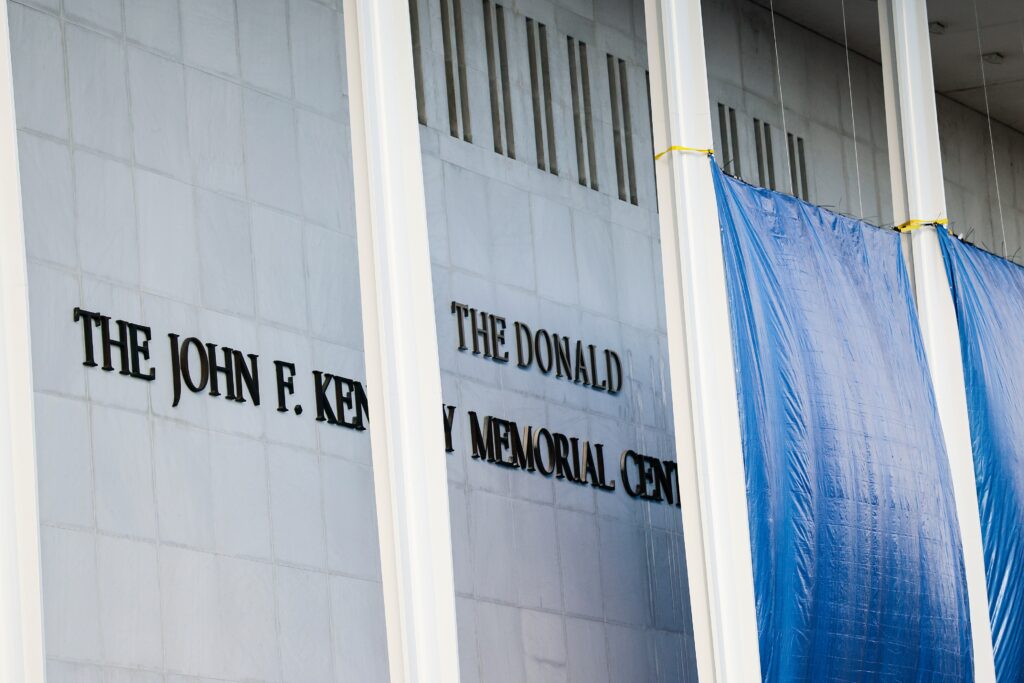

On Thursday, the White House announced that the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts would be renamed the Trump Kennedy Center, after what was reported to be a unanimous vote by the board of trustees that the president himself installed there. Trump is the board’s chairman.

The move was roundly denounced by Democrats and by members of the Kennedy family.

“Perhaps the board isn’t aware that the Kennedy Center is THE memorial to the president of the United States, John F. Kennedy,” JFK’s nephew Tim Shriver wrote on Instagram. “Would they rename the Lincoln Memorial? The Jefferson? That would be an insult to great presidents. This too is an insult to a great president.”

It is also questionable whether it could be done without Congress’s approval, given that the center was established by statute. But the new name was already being affixed to the buildingon Friday — a move very much in line with other actions taken recently by the Trump administration.

It freshly rechristened the U.S. Institute of Peace to be the Donald J. Trump Institute of Peace. Tax-deferred investment vehicles for children that are coming in 2026 will be called “Trump accounts.” And a new government website to help people shop for lower-priced drugs can be found at TrumpRx.com.

This month, the National Park Service added Trump’s June 14 birthday to its list of free-admission days. The president’s birthday coincides with Flag Day. But the Park Service simultaneously dropped its policies of not charging admission on Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Juneteenth, which unlike Flag Day are federal holidays.

U.S. Treasurer Brandon Beach confirmed in October that the U.S. Mint was drafting $1 coins featuring the image of Trump on both sides to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the nation’s founding.

Trump’s image is not among the designs for the semiquincentennial coins and medals coin unveiled by the Mint thus far, however — the idea possibly impeded for now by a law that presidents cannot appear on coins until two years after their deaths.

In 2003, there was a move among Republicans in Congress to replace Franklin D. Roosevelt on the dime with an image of Ronald Reagan. The former president was suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and unable to speak for himself, but his wife, Nancy, put a stop to the effort.

“While I can understand the intentions of those seeking to place my husband’s face on the dime, I do not support this proposal and I am certain Ronnie would not,” she said. “When our country chooses to honor a great president such as Franklin Roosevelt by placing his likeness on our currency, it would be wrong to remove him and replace him with another.”

Though the impulse of a real estate developer is to slap his name on everything around him, the nation’s past chief executives, with rare exceptions, have refrained from doing so while in office.

Perhaps the most notable of those exceptions was naming the capital city in 1791 after George Washington, the nation’s first president, who had selected the site for the federal district. The decision on what to call it was made by a three-member commission to oversee the city’s development that was appointed by Washington.

Moves to christen institutions and landmarks after history’s most well-regarded presidents have often risen from the ground up and reflected the wishes of local communities. Across the map, there are countless counties and towns, schools and libraries, streets and squares called George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln.

Sometimes, the way former presidents have been honored for their historic achievements has gone against their wishes. In 1941, Roosevelt put his hand on his presidential desk in the Oval Office, where he had signed the legislation that made the New Deal a reality, and told Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter precisely what kind of monument he would like to see to his presidency.

“If any memorial is erected to me, I know exactly what I should like it to be. I should like it to consist of a block about the size of this and placed in the center of that green plot in front of the Archives Building,” Roosevelt said. “I don’t care what it is made of, whether limestone or granite or whatnot, but I want it plain without any ornamentation, with the simple carving, ‘In Memory of ____’.”

Indeed, that modest block of stone was put into place on Pennsylvania Avenue in 1965. But a little more than three decades later, the largest and most grandiose of all presidential monuments was dedicated in Roosevelt’s honor. It stretches across 7.5 acres along the southwest side of the Tidal Basin.

And there is irony in the gargantuan Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center — a federal building eclipsed only by the Pentagon in size — given the 40th president’s aversion to big government.

A special poignance led to the naming of the Kennedy Center. The concept of a national cultural center had been kicking around for decades and was a project embraced by Kennedy’s Republican predecessor, Dwight D. Eisenhower. Kennedy and first lady Jacqueline Kennedy were enthusiasts, and helped raise money, but still couldn’t get it off the ground.

In a speech at Amherst College less than a month before his 1963 assassination, Kennedy said: “If sometimes our great artists have been the most critical of our society, it is because their sensitivity and their concern for justice, which must motivate any true artist, makes him aware that our nation falls short of its highest potential.”

“I see little of more importance to the future of our country and our civilization than full recognition of the place of the artist,” he added.

After his death, his widow asked that the center become a reality and a “living memorial” to her husband. There was still a furious fight in Congress over appropriating government money to the project — $15.5 million in federal dollars to match private donations. Republicans in particular decried it as frivolous.

But where patronage of the arts has usually been the province of the wealthy, this idea caught on with ordinary Americans.

“A great number of people throughout the United States have sent in small contributions to the Treasury and to the White House, in denominations of $1 to $25,” Rep. James C. Auchincloss of New Jersey, one of the few Republicans to support providing federal funds for the center, argued on the House floor.

The measure passed two months after Kennedy’s assassination, on Jan. 23, 1964. President Lyndon B. Johnson broke ground for the center in December.

“Pericles said, ‘If Athens shall appear great to you, consider then that her glories were purchased by valiant men, and by men who learned their duty,’” Johnson said. “As this center comes to reflect and advance the greatness of America, consider then those glories were purchased by a valiant leader who never swerved from duty — John Kennedy. And in his name I dedicate this site.”

The post Trump’s predecessors would be unsettled by his naming obsession appeared first on Washington Post.