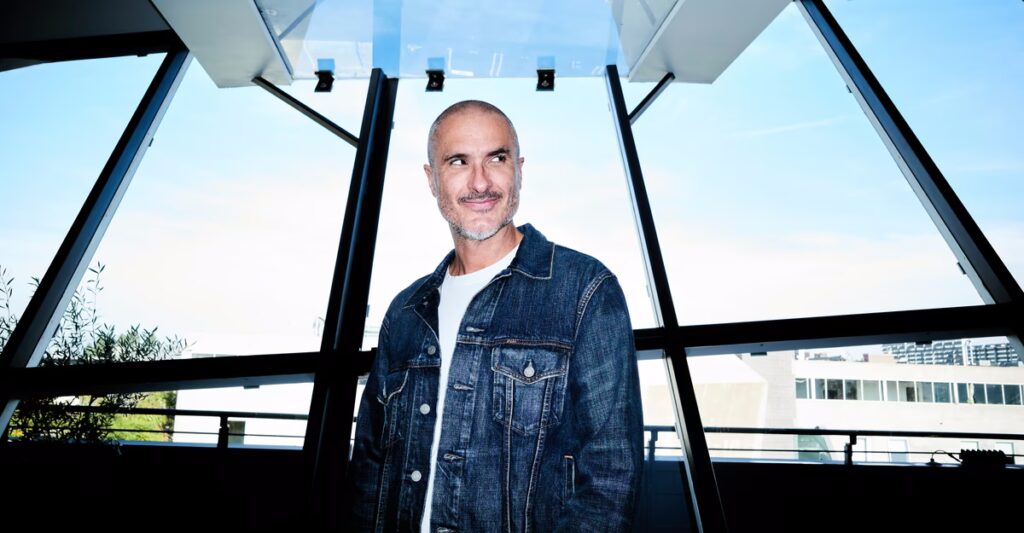

Zane Lowe, the most important music interviewer working today, kicked his sneakers up onto his couch cushions and began to cry.

For the previous two hours, I’d been asking the 52-year-old global creative director of Apple Music about problems facing the record industry: growing fears about AI; broad discontent with streaming pay rates; the ambient suspicion that music doesn’t matter as much as it used to. Lowe is famous for the high-energy earnestness he shows on his internet radio show, where he often rains intricately worded praise down on artists while tossing in a boom sound effect for punctuation. He’d answered my questions with that same jittery jolliness, but he seemed, eventually, to want to redirect the conversation—back to the power of music itself.

He picked up the remote control for his office speakers and cued up a song from the indie-folk artist Keaton Henson called “You Don’t Know How Lucky You Are.” The song’s lyrics tenderly address a long-lost lover, and the music builds from quiet guitar harmonics to a rustling crescendo. As we listened mostly in silence, Lowe laid back in his Peter Pan–green sweater, looking pained. “That’s the real stuff, man,” he said when the song was over, wiping tears from his eyes. “That’s the good shit. That’s why we do it!”

This emotional display helped answer the question I’d really been pondering: how a Gen X DJ and former rapper from New Zealand became the record industry’s favorite influencer. At a time when social media allows artists to whittle the promotional cycle down to a few Instagram posts and a Hot Ones appearance, Lowe reliably books press-shy A-listers—Taylor Swift, Thom Yorke, Tyler the Creator—for in-depth exchanges that circulate widely and define the narrative around major releases. These conversations tend to invert the ostensible purpose of celebrity interviews. Rather than serve the public’s curiosities, he said, he wants to serve artists—to give them “a place for them to learn a little bit more about themselves.”

That chummy ethos is everywhere in cultural media these days, especially across podcasting, but Lowe—who was known for his long-form chats with artists at BBC Radio 1 before he joined Apple Music upon its launch in 2015—helped popularize it. “He’s largely responsible for the new and relaxed way artists interview,” the pop singer Halsey told me in an email. “When broadcast radio was starting to decline and long before podcasts had taken over as the primary source of information sharing, there was Zane Lowe in a cozy sweater saying ‘I’m your friend, your fan, and I want you to tell me how you really feel.’” Though the conversations aren’t journalistic, they can be quite revealing about craft and the artist’s inner life. Sampha, a soft-spoken alternative-pop singer, marveled to me about the “never-ending tap of insight” coming out of Lowe. “There’s always substance behind what he’s saying—even if he’s speaking fast.”

Opinions among music listeners are more mixed. Many viewers rave about the kindness Lowe extends to their favorite artists. But to others, he’s a cheerleader for the stagnant, idolatrous record industry—someone who’d rather give a fluffy compliment than ask a pressing question. In a 2024 episode of the Pop Pantheon podcast, the critic DJ Louie XIV called Lowe a “sycophant” running the “pop-music equivalent of Fox News.” Louie’s producer, Russ Martin, added, “It is just frankly not believable that he likes every record and he likes every song on every record.”

I enjoy Lowe’s work more than that—he’s clearly smart and often amusing, and he cares a ton about the art form. Yet I, too, have wondered about his sincerity: What kind of music geek doesn’t harbor some critical opinions? But one colleague, the radio host Eddie Francis, told me Lowe refuses to speak ill of artists even when off mic, even jokingly. Another, the Apple executive Oliver Schusser, who oversees music, told me he couldn’t remember Lowe disliking anything while on the job—ever. His positivity is so committed that it almost feels rooted in fear, as though our musical era would look, without his boosting, quite sad.

Commercial radio in New Zealand—as in many places worldwide—used to be controlled by the government, which had determined that the public interest was best served by a diet of classical music and weather reports. In 1966, Lowe’s father, a young DJ, set out on a fishing boat with five friends in order to break that monopoly. Three miles off the coast of Auckland, in international waters, the crew began broadcasting rock and roll to the mainland. The so-called pirate radio station was part of a global “fight for independence of taste and communication for a generation,” Lowe said.

But that exciting life in broadcasting meant Lowe’s father was gone for much of his childhood. His parents entered a prolonged separation when he was young, and Lowe coped by obsessing over songs and bands—so much that his own friends found it grating. He asked himself the question that, he said, he’s struggled with for decades: “Why does enthusiasm, a lot of support, translate as overenthusiasm, or annoying, or cringe, or just ingenuine?”

Lowe’s enthusiasm did prove helpful to his professional aspirations—both as a rapper and beat maker (who contributed to hits that are still considered classics of Kiwi hip-hop) and as a DJ climbing the ranks of music media locally and abroad. In the late ’90s, he moved to the United Kingdom and became an MTV presenter. By 2003, he was anchoring BBC Radio 1’s vaunted nightly pop segment, where he helped break acts such as Adele and Arctic Monkeys. His Radio 1 show “was the sound of a generation” in the U.K., Christopher Tubbs, a DJ and longtime friend of Lowe’s, told me. “Tastemaker doesn’t quite cover it.”

But soon, the idea of the tastemaker was being undermined. The launch of Spotify in 2008 meant that listeners could now hear almost anything they wanted on demand, guided by personalized recommendation algorithms. Lowe’s fame was rising because of headline-making interviews with Kanye West, Jay-Z, and other rappers, but radio’s salience was declining. When Apple began working on its own streaming service, Lowe joined a star-studded leadership team that also included the record producer Jimmy Iovine and Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor.

Apple had revolutionized music listening with iTunes and the iPod, but the company was late to streaming. Reputationally, the tech was a risk; Spotify’s rise had triggered complaints from artists who felt like the new system’s ease and cheapness devalued their art. “The idea that everyone would have the same jukebox in the sky, completely virtual, terrified some of us,” Schusser said. “Does it actually make music a little bit like, I don’t know, tap water?”

Apple’s answer to the perceived issues with streaming was to market itself as a prestigious, boutique alternative to Spotify. The two services are functionally identical in many ways, allowing users to explore mostly the same pool of music using mostly the same tools. But just as Apple TV has tried to compete with Netflix by funding highbrow dramas cast with movie stars, Apple Music has invested in signifiers of old-school quality—such as human-curated radio stations.

Sitting on the wraparound couch that circles the studio, I watched a parade of musicians come in and out all morning for two days in a row. The K-pop boy band Cortis arrived with an entourage of handlers and bopped around to their own music; the trance DJ Armin van Buuren got stony-serious on the topic of his new, piano-only album. Throughout all of Lowe’s platitudes and boosterism, my attention was rapt, and my mind never wandered. His continual gush of questions, compliments, and observations creates spectacle in the manner of a top-tier inspirational speaker.

Still, I wondered whom this spectacle was for. Lowe’s previous employers, MTV and Radio 1, were, at their height, essential hubs for anyone trying to plug into pop culture. Apple’s radio shows compete for ears with its streaming efforts, whose abundance has helped diminish the sense of a musical common ground. When I first started using Apple Music in 2015, I quickly forgot about its radio tab—other than when a clip of Lowe would cross my social feeds. His interviews tend to get views on YouTube in proportion with the popularity of the featured artists; as for the radio show itself, all that Lowe would say about its reach is that it was growing. “Any artist will tell you right now, the trick is trying to find an audience,” he said.

The reason it’s so tricky is, of course, streaming and the attention economy. Standing out is not just harder than ever—the stakes are higher than ever because, as Lowe put it, “there’s an imbalance in the financials” due to the small payouts per listen. “You can work at a company and be proud of the work we do and be a part of this current model—and still feel like there’s things that you wish were different,” Lowe said. “Two things can be true.” The comment drove home that I’d been watching a deliberate anachronism: an attempt to treat “tap water” as artisanal, and to feign monoculture at a company that had helped break it up.

Lowe, however, is without obvious precedent. Celebrity interviewers have always played a promotional role and gotten cozy with their subjects, but it’s hard to think of an era-defining interviewer who didn’t at least have some bite. Kurt Loder? Nineties rockers withered under his jaded stare. Ryan Seacrest? He’s got that Hollywood-slick, smiling-but-shady thing going on. Oprah? She’ll ask the questions people want to know the answers to.

The closest pioneer of Lowe’s method might be one who walked into the studio when I was there: the 68-year-old rock journalist and film director Cameron Crowe, who was promoting his memoir, The Uncool. “I think we’re both people pleasers,” Lowe said to him. “Would you agree?”

Crowe’s trajectory in rock journalism is a modern myth thanks to his 2000 movie, Almost Famous, which is based on the same memories that he writes about in The Uncool. In the early ’70s, at just 15 years old, Crowe started writing for Rolling Stone, which gave him the chance to interview artists such as Led Zeppelin, David Bowie, and the Allman Brothers Band. His role, he told Lowe, was to be a fan: “Take the journey with that artist. If they made an album that didn’t thrill you, don’t bail; stick with it.”

This approach clashed with other people’s ideals about the profession. The rock critic Lester Bangs once warned Crowe against becoming friends with the musicians he covers. “These are people who want you to write sanctimonious stories about the genius of rock stars,” he said, according to The Uncool. “And they will ruin rock and roll and strangle everything we love about it, right?” He later added, “You should make your reputation on being honest, and unmerciful.” Bangs’s advice, repeated in Almost Famous, is a touchstone for music journalists—a reminder that being too gentle or generous can destroy the very thing you’re covering.

But Lowe has followed Crowe’s philosophy, not Bangs’s. He thanked Crowe for allowing “people like myself to be more comfortable in the fact that I don’t really have a particularly strong critical muscle.” Later, in his office, Lowe told me that although critique is important, it’s not the role he was “born to inhabit.” At base, he wants his interviews to be “a document for fans to cherish and watch over and over and over again.”

[Read: Hip-hop’s fiercest critic]

That goal neatly aligns with the record industry’s shifting prerogatives. Music consumption has largely cleaved into two patterns: the passive, casual streamer who lets the algorithm serve up good-enough background listening, and the ultra-invested “stan,” who builds a fiercely rooted group identity around their favorite artists. The new playbook for success isn’t trying to appeal broadly—it’s monetizing and remonetizing the attention of diehards.

Even so, I couldn’t help but think that he and Crowe held too rosy a view of what fans really want, especially nowadays. If you put a superfan in a room with their favorite artist, they aren’t only going to flatter and fawn. They’re going to pry for information, no matter how awkwardly. At a press conference Lady Gaga held with her fans this year, for example, the first inquiry was about a spicy topic: her relationship with the rapper and notorious troll Azealia Banks, whom she had beefed with in the past.

Lowe’s job, however, isn’t simply to follow his curiosities, as a fan might. “Just being really honest—we work as a business,” he said. Money isn’t exchanged in the booking of interviews, but certain artists may be priorities for Apple because of economic considerations, such as their potential for streaming success. “It’s not just like, you know, the Zane Lowe Show taste playground,” he said.

Artists can put preconditions on the interviews and “respectfully request that the conversation doesn’t stray into areas that might be considered a bit too sensitive,” Lowe said. “I don’t mind that. I want to know where their spirit is.” They and their representatives also, every so often, ask to give input on the final edit.

He gestured to my voice recorder while explaining why he complied with such requests. “As somebody who’s obsessive-compulsive, very aware of wanting to be thoughtful with my thoughtfulness, I personally have no problem giving any artist grace to be at their best,” he said. “And in doing so, the truth is, we get more because they trust us.” He added, “I’m not interviewing heads of state, right?”

Some of his subjects do, however, hold statesmanlike influence. Swift, for example, is so prominent that Donald Trump regularly takes potshots at her—a fact no interviewer brought up in her recent press appearances. Lowe told me he’d been allowed to ask whatever he wanted, but the topic just hadn’t occurred to him. “If I think about What am I going to ask an artist like Taylor Swift in 10 minutes?, I could set sail onto the Pacific Ocean in a rowboat and be very directionless, very fast,” he said. “That is a strong tide of overthinking.”

Additionally, no interviewers had asked her why she issued more than 30 different versions of her new album—a strategy that, by beckoning fans to buy multiple copies, allowed her to sell a record-shattering 4 million copies in one week. Many commentators have criticized her rollout method as wasteful and exploitative, but Lowe saw it as a creative bid to do what musicians need to do right now: turn music into an event. He framed it as a win not only for Swift, but for the art form. “Isn’t it nice to be in 2025, to know there are new milestones, new things that music can achieve that it couldn’t before?” he said. “Because the other option is backwards.”

One part of his interview with her had broken ground, however. Lowe asked—amid a blizzard of rhetoric about the importance of human connection—how Swift had been processing the public reaction to The Life of a Showgirl. “The rule of show business is: If it’s the first week of my album release and you are saying either my name or my album title, you’re helping,” she replied. She added, later, “I have a lot of respect for people’s subjective opinions on art. I’m not the art police.” These quotes ricocheted around the internet, taken as a sign that Swift was well aware of how many fans and critics had panned the album. Lowe hadn’t mentioned that mixed reception, but he hadn’t needed to. Celebrities can be as online as any of us—they know what their detractors think.

It’s this reality that Lowe and the new music-promo circuit try to guard against. The background hum of digital life is negativity, polarization, and jaded disengagement; the record industry craves a forum to pitch its narratives before they’re torn to shreds in comment sections and mined for TikTok drama. A healthier artistic ecosystem wouldn’t—and in the past, didn’t—need the “safe place” that Lowe professes to provide.

That ecosystem seems unlikely to grow healthier as technology progresses. AI-generated songs have recently begun flooding streaming services; Spotify listeners can call upon an artificial DJ to deliver banter and commentary tailor-made for the user. When I brought up AI to Lowe, it was the first time I heard him express open contempt. “Leave the arts alone, dude. Like, go and fix other shit,” he said. Regarding the prospect of an AI hitmaker, he asked: “By the way, how do I interview that person?” His voice had been growing louder, occasionally hitting a near-shout.

Minutes later, before grabbing the remote control to play Keaton Henson’s song, he clapped his hands and stared me straight in the eyes. “Music is magic,” he said. “It guides us and helps us in moments subconsciously and consciously all the time. It’s such an important part of being human. It’s such an important part of our experience that I think, without meaning to, we let it evaporate into everything.”

By this point, the authenticity of his idealism was hardly in doubt, but the anxious process required to maintain it was becoming clearer. I didn’t need to be told that music is magic; I’d never really questioned it. Then I remembered what he’d told me about interviews: They’re for the benefit of the subject.

The post The Music Industry’s No. 1 Fan appeared first on The Atlantic.