As the 2026 midterm elections approach, the perceptive and pocketbook-focused American voter is concerned about one thing above all: the cost of living. According to a new report from Goldman Sachs chief U.S. political economist Alec Phillips, this economic frustration has placed President Trump’s aggressive tariff regime in the political and legal crossfire, creating a scenario where trade barriers are likely to come down rather than go up in the coming months.

With mid-term elections coming up in March, Phillips notes that the cost of living remains the “top issue of concern to voters,” with a higher percentage citing it now (29%) than ahead of the 2024 presidential election (25%). Using data from prediction markets platform Kalshi, Phillips argues that the consensus expectation is that Democrats are “much more likely” to win the House majority next year. There is one overwhelmingly clear choice to make, he adds: “The most obvious policy lever to pull would be tariff reductions.”

Whether this occurs is far from certain, as the Trump administration has fiercely defended the tariff regime, even if they keep getting smaller and lower. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent recently admitted to New York Times Dealbook editor Andrew Ross Sorkin that they are a “shrinking ice cube.” Bessent has said he opposed the tariffs at the beginning of 2025, changing his mind when he saw how many other countries were willing to come to the table.

Still, Democrats smell blood on the issue. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer has reportedly urged his party to double down on “affordability,” after his party swept off-year elections in early November, running on the theme. Candidates from the center (New Jersey’s Mikie Sherrill) and the far left (New York City’s Zohran Mamdani) alike made hay on the issue. Gene Sperling, director of the National Economic Council under Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama and was a senior adviser to President Joe Biden, argued recently in Bloomberg Opinion that the affordability crisis is real and can be traced back directly to the creation of the tariffs regime.

Federal jobs data lend support to Sperling’s argument, with anemic growth setting in from April onward, exactly when Trump rattled markets by announcing a worldwide “reciprocal tariff” regime, which he called “Liberation Day.” The longest federal government shutdown in history deprived Wall Street of jobs data for several months, but it belatedly revealed yet more anemic employment growth—and the highest unemployment rate in four years. Bank of America Institute added more context to the picture by showing that small business profitability fell in November for the first time in a year-and-a-half, attributing the price hikes and hiring struggles they’re enduring to one likely cause: tariffs.

President Donald Trump may also be unwilling to admit political reality. He has repeatedly rejected the public’s increasingly disaffected stance on the economy. He repeatedly called the concept of affordability itself a “hoax,” gave himself an “A-plus plus” on the economy and spent a prime-time address in late December lecturing Americans about how they aren’t appreciative enough of the great economy, despite statistical evidence to the contrary. But will long odds in the midterms focus Trump’s mind on tariffs?

How the tariffs could crumble

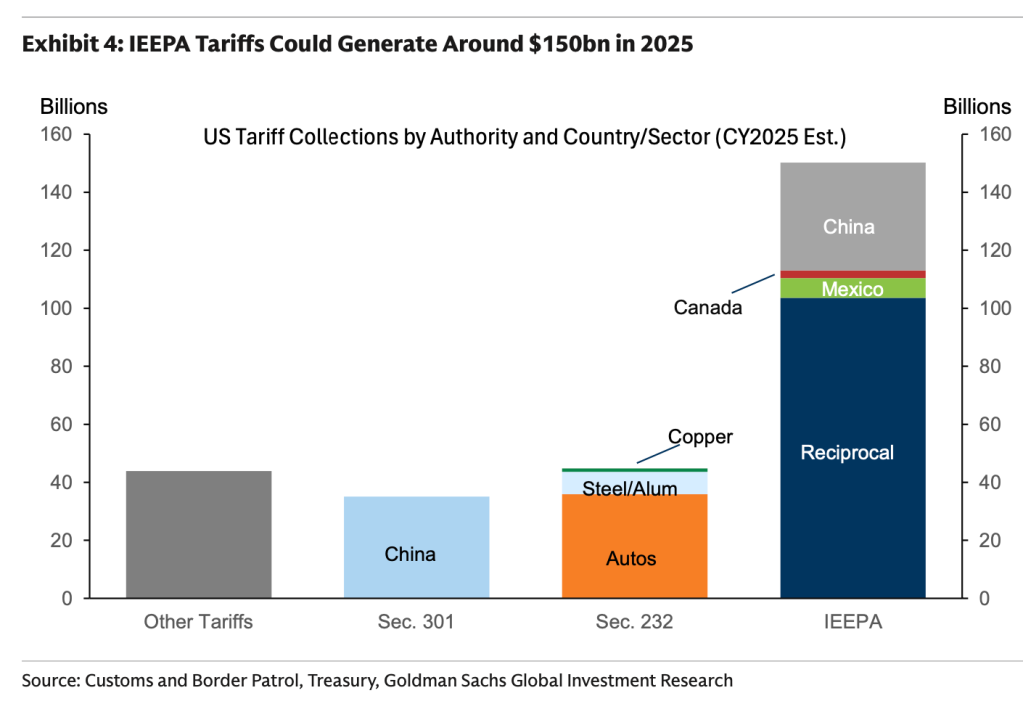

The mechanism for this reversal is likely to be a mix of political necessity and judicial intervention. Goldman Sachs, as many other analysts have done, predicts that the Supreme Court will rule early next year that the majority of Trump’s tariffs are illegal since he does not have the authority to impose them under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). Oral arguments suggested that a majority of the court believes the administration exceeded its authority, potentially invalidating tariffs that account for a significant portion of the effective rate increases seen this year.

While the Trump administration may attempt to reimpose tariffs using different authorities, legal and logistical hurdles should act as a de facto ceiling on trade aggression. The White House could pivot to Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 as an interim measure, but that only authorizes tariffs for 150 days, capped at 15%—a far cry from many of the IEEPA tariffs and certainly below the outliers, like Trump’s 50% tariff on India.

While Section 123 tariffs are temporarily in place, the US Trade Representative could investigate and finalize Section 301 investigations into major trading partners, allowing the White House to impose longer-lasting tariffs to replace the IEEPA ones. Consequently, Goldman expects the effective tariff rate to decline by around two percentage points by the end of 2026.

The voter’s acute awareness of economic pain has also hamstrung the administration’s attempts to use fiscal policy to offset trade war costs. President Trump’s proposal for a $2,000 per person “tariff rebate” has failed to gain traction among congressional Republicans, with prediction markets sending the probability of imposition down to just 2%. Republican lawmakers are increasingly reluctant to support payments to households that are merely recycling revenue extracted from those same consumers via higher import costs.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget calculated that sending the $2,000 checks would cost $600 billion, about twice as much as the annualized revenue once contemplated from all of the tariffs in place. The IEEPA tariffs have collected about $130 billion year-to-date, Goldman calculates, with another $20 billion or so due to come before the new year. If the Supreme Court rules against the tariffs, importers are also likely to receive refunds eventually, but that could take several months of legal wrangling to clear up.

Furthermore, the administration is retreating from opening new fronts in the trade war before the votes are cast. While investigations into sectors like pharmaceuticals and semiconductors are ongoing, Goldman Sachs does not expect new tariffs in these areas to take effect in 2026, due in part to the “potential negative political consequences” of raising prices on essential goods. Even the US-China relationship, usually a source of volatility, is expected to be “much more stable” over the coming year, with a deal already in place to reduce certain IEEPA tariffs on China from 20% to 10%.

Faced with a skeptical Supreme Court and a restless voter base that cannot be placated by unfunded rebates that are unlikely to materialize anyway, the administration appears poised to let the air out of its trade war. But the question remains: will they (or Trump) let that happen?

The post The American voter is angry about one thing above all and Trump’s tariffs are in the crossfire, Goldman’s chief political economist says appeared first on Fortune.