Science Corporation, the brain-computer interface startup founded in 2021 by former Neuralink president Max Hodak, is launching a new division of the company with the goal of extending the life of human organs. And no, not brains.

Alameda, California-based Science is aiming to improve on current perfusion systems that continuously circulate blood through vital organs when they can no longer function on their own. The technology is used to preserve organs for transplant and as a life-support measure for patients when the heart and lungs stop working, but it’s clunky and costly. Science wants to make a smaller, more portable system that could provide long-term support.

Until now, Science’s focus has been on neural interfaces and vision restoration. The company is working on a “biohybrid” interface that uses living neurons instead of wires to connect to the brain. More immediately, it’s looking to commercialize its retinal implant, which successfully restored some vision in patients with advanced macular degeneration, allowing them to read letters, numbers, and words. Science acquired the implant in 2024 from French startup Pixium Vision, which was facing bankruptcy, and has leapfrogged ahead of Elon Musk’s Neuralink to develop an implant for vision loss.

“In some sense, they’re both longevity technologies, and that is the goal of both the neural interfaces and this,” Hodak says of organ perfusion.

Hodak cofounded Neuralink along with Musk and others in 2016 but left in 2021 to start Science and serve as its CEO. Since its founding, Science has raised around $290 million, according to the venture capital database Pitchbook.

Hodak was inspired to work on organ preservation after reading about the case of a 17-year-old boy in Boston whose lungs had failed due to cystic fibrosis. He was being sustained by a type of perfusion called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, while awaiting a transplant. But after two months on the wait list, he developed a complication that made him no longer eligible for a transplant. His doctors and parents faced the ethical dilemma of keeping him alive on ECMO, which is meant to serve as a short-term bridge. Eventually, the machine’s oxygenator began to fail and doctors chose not to replace it. Shortly after, the boy lost consciousness and died.

Used during the Covid-19 pandemic for patients whose lungs had failed, ECMO machines are expensive and highly resource-intensive. They cost thousands of dollars per day to run, and patients are tethered to them in the hospital. Consisting of a large circuit of tubes that must be wheeled around on a bedside cart, they require constant monitoring and frequent manual adjustments. Because of their high cost, not every hospital has them.

“Could you get to the point where you could check a kidney as luggage on a United flight to the East Coast or build a system where that kid could have brought home a backpack rather than just needing to have the life support withdrawn?” asks Hodak.

Beyond ECMO, perfusion systems that are meant to prolong organ life outside the body for transplant are also pricey. Massachusetts-based TransMedics makes an organ care system that costs around $250,000 for the machine plus $40,000 to $80,000 per use. If organs have to travel far distances, they’re transported by the company’s fleet of private jets.

A small team at Science has built a perfusion system from scratch and is now able to keep rabbit kidneys alive outside the body for up to 48 hours. Hodak says they’re working to expand that to a month by next spring. A human kidney can remain viable out of the body for 24 to 36 hours—longer than hearts and lungs—if stored on ice. Existing perfusion machines can extend this viability time to four days or longer.

Branching into organ perfusion was always part of Hodak’s plan for Science, which now has about 170 employees. “We needed to do some preliminary work to get the conviction to make a bigger bet on it,” he says.

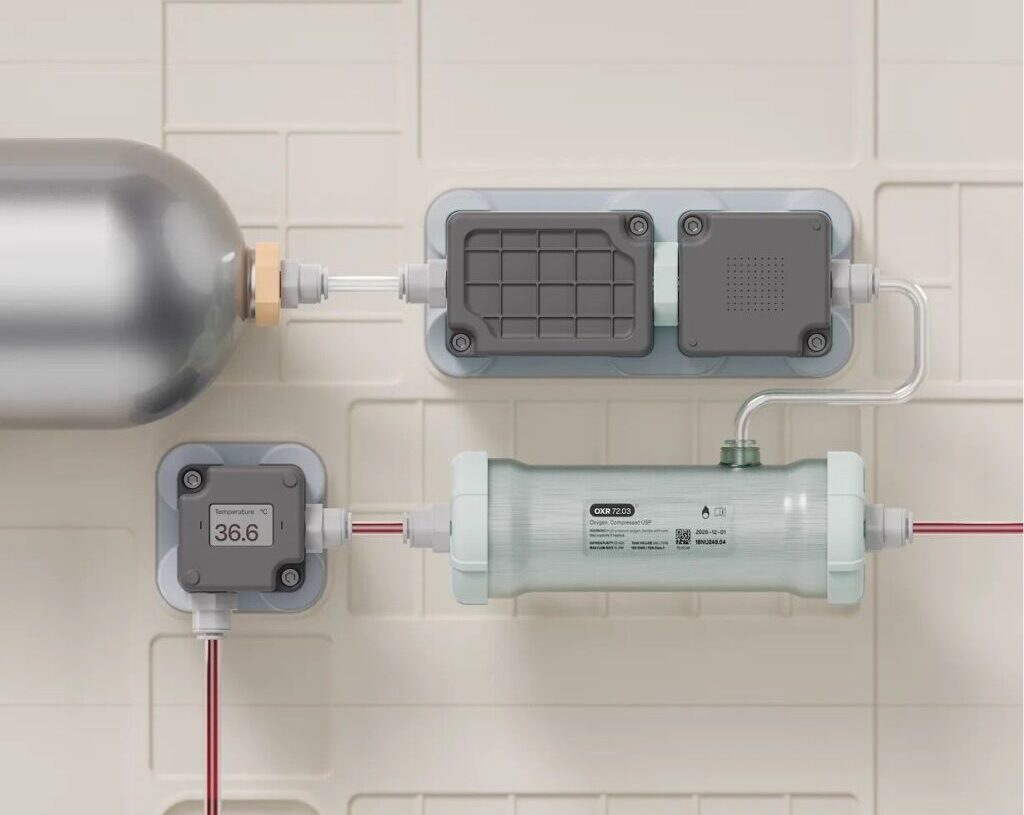

The company’s prototype has integrated sensors to monitor blood oxygenation, flow rate, pressure, and temperature in real time and a modular design with swappable components to support different organs and applications. Close-looped control allows it to make automatic adjustments, where current ECMO machines must be manually controlled.

Science will be competing against several other companies that make automated perfusion systems for organ transplants. While these devices are becoming more common to help preserve organs outside the body, they remain costly and often require specially trained staff. Hodak doesn’t have an exact price point in mind, but is hoping to make a more affordable option.

“There’s this big gap between what this technology is fundamentally capable of and how it is being deployed and used in daily practice,” Hodak says. If Science manages to close that gap, “it really takes you from this world of conventional medicine and many of its very difficult problems to potentially a world of swappable parts.”

The post Former Neuralink Exec Launches Organ Preservation Effort appeared first on Wired.