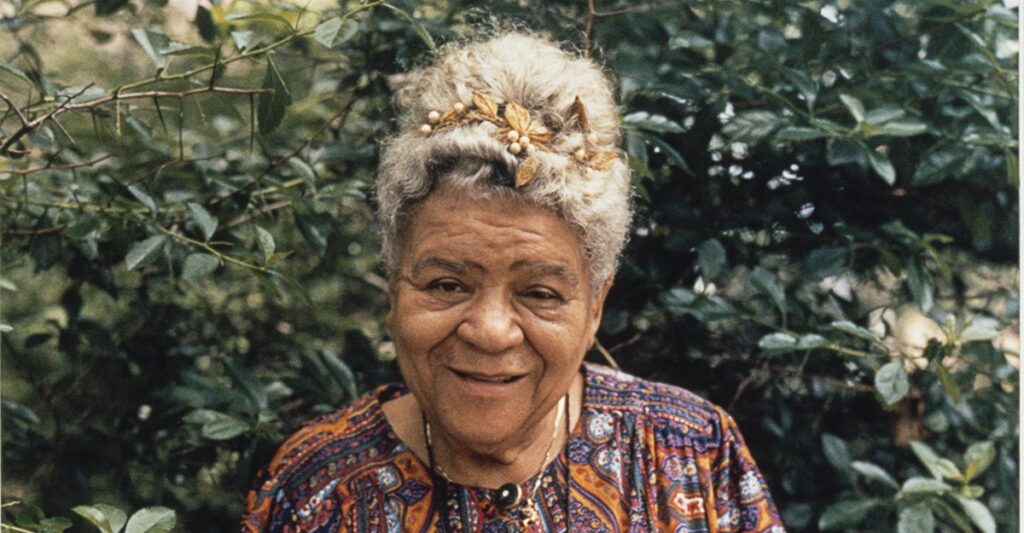

Midway through William Greaves’s documentary Nationtime, which follows the 1972 National Black Political Convention, a woman named Audley Moore stands in a busy hallway preaching to people’s backs. She is clad in a burgundy-and-navy-floral kaftan and matching headwrap. Her voice rings out amid the bustling crowd of convention-goers: “Now let me tell you: Benjamin Franklin said, ‘Those who seek temporary security rather than basic liberty deserve neither.’ I’m demanding reparations. That’s all I can see now. That’s the answer for our people.” She is paraphrasing Franklin’s quote, one whose meaning is frequently misconstrued, but the invocation of the Founding Father lends both heft and irony to her calls for redress from the American government. Moore catches a few passersby and jokes with them, shoving a typewritten paper in their hands as they walk away. A few stay to listen. This scene aptly encapsulates the life of Audley “Queen Mother” Moore, an often-overlooked Black-nationalist organizer who fought vociferously for Black self-determination until her death in 1997.

A laudable new biography, Queen Mother: Black Nationalism, Reparations, and the Untold Story of Audley Moore, by the historian Ashley D. Farmer, uses Moore’s story to chart a trajectory of Black-nationalist activism in the United States, from Garveyism in the 1920s (Moore belonged to the New Orleans chapter of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, or UNIA) to the 1995 Million Man March for Black-male unity and self-empowerment. Moore’s radical ideas—including her desire for a separate Black nation in the South—earned her ridicule at times, but her sharp critiques of American white supremacy also found purchase, influencing activists such as Malcolm X, Muhammad Ahmad, and Charles J. Ogletree Jr.

Despite her prolific political organizing and wide reach during her lifetime, Moore has largely been omitted from the history of civil-rights activism. Her exclusion from traditional archives is a familiar story to scholars of Black American life, especially those who study the contributions of women. Farmer writes that her book, which she spent a decade researching and writing, required painstaking effort to locate traces of Moore in personal papers, land deeds, files from the FBI and the House Un-American Activities Committee, oral-history tapes, and lingering memories (much of Moore’s ephemera were lost in a house fire). The resulting work, which examines her involvement in a strikingly diverse roster of organizations, is a portrait of a woman with uncanny savvy and flexibility.

Moore worked with nationalists, Communists, and moderate liberals, white and Black alike—whatever it took to pursue goals such as fair housing regulations, just labor laws, and equitable resource distribution. She was sometimes self-contradicting as an activist, which isn’t to say she wasn’t singularly dedicated to her cause. She seems to have simply understood that achieving her objectives—in all their multiplicity—required maximal fluidity. Activists with unchanging missions might be easier to pin down (and thus less likely to be forgotten). But Moore’s story shows that the Black-nationalist movement also encompassed people who were willing to find areas of compromise in order to get the job done.

Moore was born in 1898 in New Iberia, Louisiana, to a well-off family that descended from both enslaved and free Black communities. But both her parents died before she reached adulthood, and she was forced to turn to domestic work in white households, one of the few economic avenues available to her at the time. In the violent, segregated South during World War I, Moore “looked on as America made its grand debut on the world stage as a great emancipator—a masterful public performance as liberty’s beacon shining from the West, all while extending white supremacy’s tendrils across the globe,” Farmer writes. Having noticed that the Army didn’t offer as much support for Black soldiers as it did for white ones, Moore and her two sisters provided meals and recreation space to these troops in Anniston, Alabama. Losing the protection of Black elite society that her parents had afforded her, and witnessing the contradiction between America’s actions abroad and at home, helped shape Moore’s lifelong advocacy for civil rights and for working-class concerns.

[Read: A blueprint for Black liberation]

It is difficult to overstate the influence on Moore’s development of Marcus Garvey, the foremost Black nationalist of the 20th century. Garvey sought to revitalize “Africa for the Africans,” and to repatriate people of African descent to their motherland. He also championed Black pride, self-reliance, and racial separatism on the basis that white people would never recognize Black people’s human rights. His teachings showed the fledgling activist how to analyze Black people’s social conditions and gave her the desire to unify Black people everywhere. In 1922, Moore joined the UNIA in New Orleans, attending meetings and studying the history of the global African diaspora. She and her then-husband once even packed up all of their possessions, planning to expatriate to Liberia as part of one of Garvey’s “Back to Africa” initiatives, before ultimately deciding to stay in the United States.

After Garvey was deported in 1927 following a mail-fraud conviction, Moore was forced to channel her activism into vehicles beyond the declining UNIA. A move to Harlem brought her into the orbit of the Communist Party. A card-carrying member by 1936, Moore cut her teeth protesting racist and sexist discrimination across New York City, forming tenants’ rights organizations, and sending aid to Ethiopia after a 1935 invasion by Italy. In response to Black Communists’ demands that the party address both class and race oppression, Communist leaders had come to believe that Black people constituted an oppressed nation, and that it was within the party’s interest to fight for their rights. But Moore’s association with the Communists was less of an ideological commitment, Farmer writes, than a practical way to work toward Garvey’s “anti-imperialist, pro-Black” goals. Collaborating with the moderate NAACP, Moore advocated for the freedom of five of the Scottsboro Boys, a group of nine Black teens falsely accused of raping two white women in Alabama.

Moore also worked on many causes tangential to Black nationalism, including lowering the price of milk for children and boycotting goods from Nazi Germany. Among her other “strange bedfellows,” Farmer mentions Mary McLeod Bethune’s respectable, middle-class National Council of Negro Women,“an unlikely place for a Black Nationalist and Communist” who was primarily self-educated. But Moore’s success in organizing with Communists had taught her that, as Farmer writes, “an organization need not be explicitly Black Nationalist in its mission to advance the cause.”

“The cause” itself, for Moore—and, truthfully, for many Black nationalists—couldn’t be distilled into a clear, unified goal. As James Edward Smethurst, a scholar of 20th-century Black radical movements, writes in his book The Black Arts Movement, the actual definitions and tactics of Black nationalism were secondary to the belief that, without self-determination, Black people would be “oppressed and exploited second-class (or non-) citizens in the United States.” Moore’s activism exemplifies how, as Smethurst writes, “old Left and old Nationalist spaces often intersected with each other and with those of the New Left, the Civil Rights Movement, and the new nationalists,” particularly Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam, “in surprising ways.”

In 1950, Moore fell out with the Communist Party because of its shifting focus away from Black equality. Over the next two decades, her politics would harden; she mentored many young nationalists, including Malcolm X and Ahmad, a founder of the Revolutionary Action Movement. But as Farmer writes, guiding all of Moore’s work was a single overarching dream, rooted in her early days with the UNIA: gaining reparations. In 1962, Moore launched a campaign to persuade the U.S. government to pay reparations to descendants of enslaved Africans, which she timed for the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation the following year. She and her fellow activists charged that the country owed Black Americans $500 trillion, to be paid in land and cash distributed to individuals annually. She even sought the formation of a separatist Black nation in the U.S.—what she called a “national territory in a country developed by our blood and tears and unrequited slave labor.” This was groundbreaking at a time when the zeitgeist prioritized inclusion in the American body politic rather than separation and redress.

In the 1960s, Moore would become known by the honorific “Queen Mother Moore,” in recognition of her role as an elder stateswoman to Black organizers across the political spectrum. During a trip to Ghana in 1972, she was crowned with the title in an Asante ceremony. In the ’70s, she reached the height of her influence in the Black Power Movement, becoming a mentor figure to a Detroit-based separatist group, the Republic of New Afrika, that advocated for five Black Belt states to be given to Black Americans as a nation-state. In spite of the group’s unrealized dreams—as well as struggles with surveillance and violent disruption from the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program, or COINTELPRO—Farmer writes that Moore still affirmed, at the end of the ’70s, “I’m a hard nationalist.”

[Read: A book that puts the life back into biography]

In Queen Mother, Farmer takes a clear-eyed look at Moore’s foibles, noting her absenteeism during her son’s formative years, her embrace of patriarchal hierarchy in Black communities, and her exhortations for Black women to embrace polygyny to facilitate nation building. Farmer acknowledges that Black nationalists sometimes took violent action, claiming the “right to govern themselves and to defend themselves.” But she also seeks to correct a common misunderstanding of the ideology, arguing that it’s not the “violent, incoherent, and nihilistic inverse of the Civil Rights Movement,” but a campaign with the very same goals, sought through different means (separation from white society, rather than integration). Still, many of Moore’s ideas “were on the fringe then,” Farmer writes, “as they are now.” The historian doesn’t explain away Moore’s infatuation and personal association with the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, who in 1975 invited her to attend a meeting of the Organization of African Unity in Kampala. As Farmer writes, Moore was “thrilled” by him and seemed to ignore the fact that his rule had become known for its corruption and human-rights abuses.

But Farmer doesn’t need to justify all of Moore’s beliefs and goals to make a case for her influence. Her meticulous study of the many figures, movements, and organizations Moore worked with shows that her contributions were pivotal, rather than peripheral. Moore was a Garveyite through line—what Farmer calls a midwife—to many 20th-century Black-nationalist activists, a lot of them men, who remain more famous than her. Queen Mother establishes her as a titan in her own right, a central influence in nearly a century of global Black-liberation struggles, and a reminder for modern activists of a persistent truth: that cooperation does not have to mean compromising one’s values, and that those who dream of freedom have more than one way of achieving it.

The post The Midwife of Black Nationalism appeared first on The Atlantic.