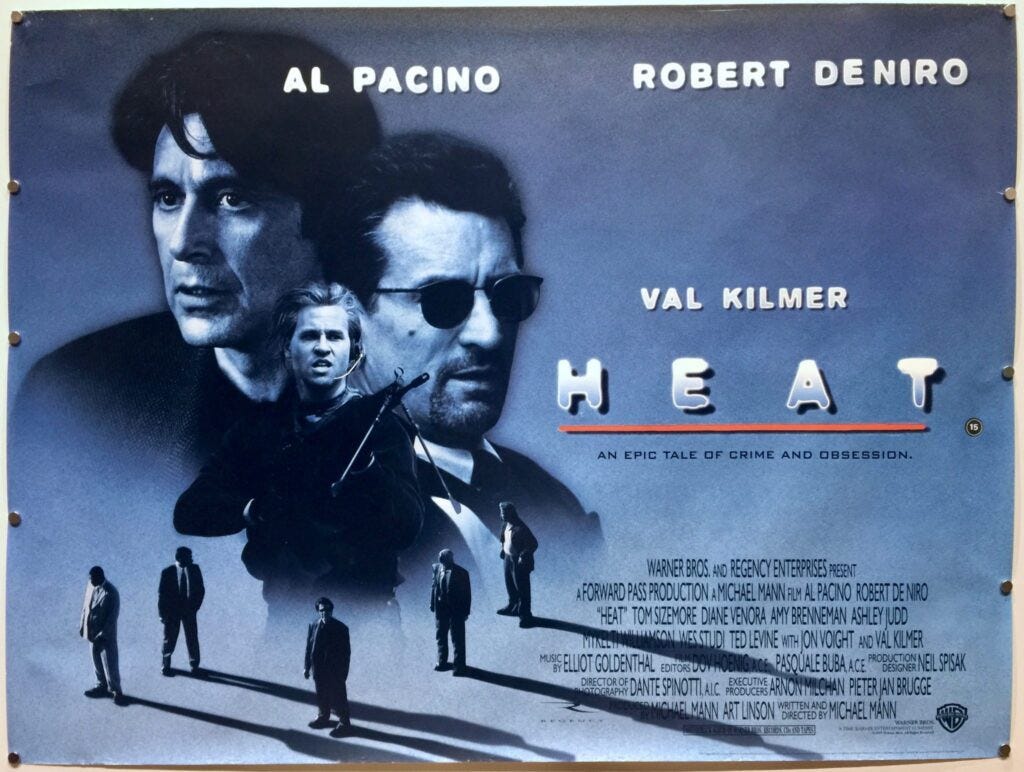

As a typical millennial man who drinks continental lager, wears Carhartt, and likes to blame all of his problems on vague nefarious forces like ‘late-stage capitalism’ that I luckily can’t do anything about, I love Heat, the 1995 Michael Mann heist classic that hit cinemas 30 years ago this week. It stars Al Pacino and Robert De Niro as Vincent Hanna and Neil McCauley and details their obsessive, co-dependent cop-and-robber relationship, which suffocates every other aspect of their lives.

I have a friend who calls it ‘Boy Trash,’ putting it in the same category as Point Break, The Rock, Face/Off, and the spiritual successor to Heat, The Town, all of which offer a basic plot, lots of action, and usually a smattering of Men’s Mental Health to make it feel like you haven’t just been watching two men run around shooting fake guns at each other for three hours. I think Heat is too good to be associated with the word ‘trash’ in any way, but if I relent and play the game then Heat is surely the alpha and omega of ‘Boy Trash,’ a divine dreamscape for any man who is tired of the world asking him to have patience and coherent emotions.

I was reminded of this when I found myself watching it (again) for a sold-out anniversary screening in central London. Sure enough, just like every other time I’ve watched it, each male character manages to fuck over his female love interest in some way or another with his own stupid, kamikaze compulsions. Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer) mumbles: “The sun rises and sets with her, man,” about his beautiful wife Charlene (Ashley Judd), but still destroys her life through anger, gambling, and crime regardless. Even as Trejo (Danny Trejo) lays dying he chokes out the words, “My Anna’s gone, gone.” But she’s only gone, brutally slain in the room next door, because he refuses to stop getting involved in crazy heists.

The arc of Donald Breedan (Dennis Heybert) summarizes the doomed romanticism and inevitable catastrophe of Heat better than any other in the film, despite him playing a relatively miniscule part in its plot. Freshly released from prison, Donald is subjected to a degrading life of parole, finding himself at the whims of a horrible boss at a local cafe, who steals his pay and treats him like shit.

Yet through it all, his partner Lillian (Kim Staunton) is there supporting him, driving him to work, telling him how proud she is that he’s trying to turn his life around, loving him through the fug of downtrodden self doubt he is engulfed by.

“In the world of Heat, there are no stars, only city lights, which twinkle on indifferently in the background of every scene, like a distant father the men in the film can’t stop trying to impress”

Then Neil McCauley catches Donald unawares at work and asks him to be his getaway driver. He thinks ‘Fuck it, why not,’ beats up his boss, and heads off to get shot dead by the police. He is the quintessential male character in Heat, and maybe in all ‘Boy Trash’ movies: tragically compelled to throw it all away in an instant because consciously or not he has sworn to live by the film’s immortal maxim, as so memorably incanted by Michael Cheritto (Tom Sizemore): “The action is the juice.”

Cheritto himself has a wife, kids, and investments, but when faced with the prospect of one more bank robbery with the lads, he just can’t resist. In the world of Heat, there are no stars, only city lights, which twinkle on indifferently in the background of every scene, like a distant father the men in the film can’t stop trying to impress. There are no lofty aspirations beyond the perfume cloud of the here and now. Nothing to aspire to except the chance to live forever in one boundless moment where you act first and don’t think about the consequences, because standing still is a great way to realize that existence is too absurd and painful to bear.

Again: The action is the juice.

As a certified millennial navel gazer, I can’t help but relate to footsoldiers like Donald, Chris, and Michael. They might feel like they are raging against forces beyond their control, but really it’s just themselves. And rather than change course, their reaction is to plough their lives headfirst into the nearest wall. In reality, there is a lot of love on the table for these men, and there is much that they can actually control. They all have jobs, roles to play, friends, lovers, and at least a modicum of self determination. But they just don’t care, because they know best, even if knowing best means believing you’re the worst.

Is this behavior mindful, considerate, or in any way conducive to long-term happiness? No. Like nearly all of the men in the film, they die violently and without ceremony, leaving behind them a trail of grief and ruin. But this is what makes Heat so great. The fact that it doesn’t try to sermonize. Not really. It is, after all, a three-hour action movie. At some point, the moral lesson has to stand aside. Instead, it leans into the adrenalizing, verboten joys of living in a way that is both selfish and self destructive. Diving deep into the various written tributes published this week, acknowledgement of this seemed lacking. Yet there is a reason why Heat has been calling a certain type of man towards it like a siren song for the last three decades.

The reason is the action, and the action is the juice.

If you could summarize the mindset that McCauley and Hanna share, you might quote one of the former’s key lines: “I am alone. I am not lonely.” The two main characters’ all-consuming death drives eventually lead them to the only true moment of psychic connection they experience in the film: when McCauley is bleeding out with one of Hanna’s bullets lodged in his chest.

“I had to take the emotional quotient to that exact moment when McCauley is dying, and he’s fortunate enough to die with somebody [Hanna] he’s that close to, the only person on the planet that has the same kind of mindset he has,” explained Michael Mann ten years ago, in an interview with Rolling Stone to mark Heat‘s last decadal birthday. “But at the same time, he’s also the person who shot him, and that duality is not a contradiction—they’re both true.”

Whether you call it Bushido, the Art of War, or just the warrior’s code, men love an abstract set of moral and behavioral guidelines that draw them together and sanctify their mutual annihilation. In Heat, nothing else matters to McCauley and Hanna except their shared obsession, which takes over completely to the point that everything else—love, happiness, reason—falls by the wayside. It’s a hair’s breadth from being intensely romantic, like a gothic novel. Wuthering Heights with guns. Jane Eyre for the fellas.

“Being self absorbed, reckless, and borderline insane usually does end badly”

The two characters blur the lines between protagonist and antagonist. By the end, you’re not really sure which is which. McCauley is a dangerous recidivist, willing to kill civilians and abuse women for his goals. He lives by the other big rule from Heat: “Don’t let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner.” Yet you root for him. Hanna is trying to prevent crime and capture the bad guys, yet his determination is disconcerting and hard to cheer for. He’s on his third marriage, constantly coked up, and so neglectful of his wife and step-daughter that she attempts suicide. When he and his adversary sit down for a chat over a coffee, in a scene widely lauded as one of the finest in modern cinema, it’s like two old friends with a toxic addiction problem gearing up to spur it on for what they know will be the last time.

And that’s kind of the point. No one wins. Being self absorbed, reckless, and borderline insane usually does end badly. But it’s still impossible not to idolize the heroes of Heat as they soar and thrust forward into their beloved moments, bursting out the other side of those moments like clenched firsts through the same brown paper bag, the beautiful, exhilarating moments that they live and ultimately die for, ill-fated men of action who go out on their swords and in great suits.

In a turgid millennial world, with its eight-hour screen times and miserly way with volition, you’re largely given two choices: accept whatever shit comes your way or ineffectually complain about it. Frustrated, the latter often becomes something else, then misdirected: ire aimed at the wrong people, the ones closest to us. We lash out and fuck ourselves over then refuse to take responsibility, which just wants to make us lash out even more. We’re stuck in an endless, impotent loop, so what’s the answer?

Maybe it’s recalibrating the way we think about the world. Realizing that the end result—a singing balance sheet, a property portfolio, a racehorse, a yacht, or a trophy partner—isn’t really the thing to aim for at all, and that actually, it’s the aiming itself that’s the whole point. Maybe it’s as simple as getting out and doing something. Putting on a gray three-piece suit, a hockey mask, or some 1990s sunglasses. Learning about complex metals, yearning, or smashing up a TV. Going out and having a life, even if it kills you.

Because if the action really is the juice, who cares how it ends?

Follow Tom Usher on Instagram @_tomusher

The post ‘The Action Is the Juice’: Why Self-Destructive Men Love ‘Heat’ appeared first on VICE.