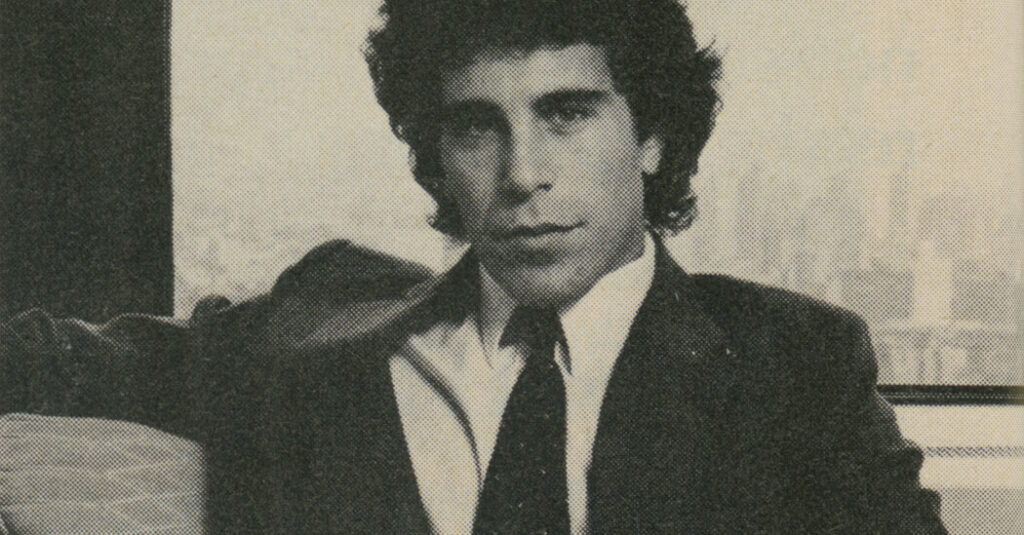

One evening in early 1976, a bushy-haired Jeffrey Epstein showed up for an event at an art gallery in Midtown Manhattan. Epstein was a math and physics teacher at the city’s prestigious Dalton School, and the father of one of his students had invited him. Epstein initially demurred, saying he didn’t go out much, but eventually relented. It would turn out to be one of the best decisions he ever made.

At the gallery, Epstein bumped into another Dalton parent, who had heard tales of the 23-year-old’s wondrous math skills. The parent asked if he’d ever thought about a job on Wall Street, according to an unreleased recording of Epstein and a document prepared by his lawyers. Epstein was game. The parent dialed a friend: Ace Greenberg, a top executive at Bear Stearns. Epstein, the friend told Greenberg, was “wasting his time at Dalton.”

Greenberg invited Epstein to the investment firm’s offices at 55 Water Street at the southern tip of Manhattan. Epstein showed up in a turtleneck. Greenberg was impressed — even though the young man didn’t have the foggiest idea of how Wall Street worked. Greenberg had helped build Bear Stearns into one of the industry’s scrappiest firms by eschewing the traditional investment-banking practice of hiring Ivy Leaguers with M.B.A.s. He preferred what he called P.S.D.s: those who were poor, smart and had “a deep desire to become rich.”

Epstein fit the bill. He grew up in a working-class family in Coney Island. Friends described him as a math whiz and a piano virtuoso. And, as Greenberg and his colleagues would soon learn, he yearned for wealth. That trait had been apparent as early as ninth grade: A classmate told us that Epstein predicted to her that one day he would be very rich.

Before offering Epstein a job, Greenberg had him meet another senior executive, Michael Tennenbaum. His son happened to be a Dalton student, who reported to his father that Epstein was popular with students and the school’s young female staff members. Epstein went to Tennenbaum’s office overlooking New York Harbor for an interview. “He was just a hell of a salesman,” Tennenbaum told us. Epstein was hired.

It was an extraordinarily lucky break for him — the first of many. Administrators at Dalton, unimpressed with Epstein’s teaching, had asked him to leave the school after the academic year ended. Now, just like that, he had a new job that paid about $25,000 a year (roughly $140,000 in today’s dollars).

Greenberg viewed the young man as a protégé. Early on, he invited Epstein to a dinner party and seated him next to his 20-year-old daughter, Lynne, who told us that she suspected it was a setup. The two hit it off and started dating. Word of the new guy’s romance with the boss’s daughter spread quickly, granting Epstein something akin to protected status at the firm.

Tennenbaum soon became Epstein’s supervisor. “He was proving to be quite talented,” Tennenbaum told us. But in late 1976, he received a disconcerting phone call from the head of Bear Stearns’s personnel department. Employees had belatedly gotten around to checking Epstein’s résumé, which stated that he had received degrees from two California universities.

“Are you sitting down?” the H.R. official asked Tennenbaum. “Neither school has heard of him.”

Tennenbaum was in a delicate spot. He asked Greenberg what to do. The response, Tennenbaum told us, was that he should treat Epstein as if he were a normal employee — an instruction that made clear that, thanks to his relationships, Epstein was in fact not a normal employee.

He summoned Epstein to his office. “You lied about your education,” he said.

“Yes, I know,” Epstein calmly replied. He had never graduated from college. Tennenbaum recalls being disarmed by the admission. Decades later, he would regard it as an example of Epstein’s ability to manipulate his marks — in this case, him.

“Why did you do it?” Tennenbaum stammered.

Without an impressive degree or two, Epstein said, “I knew nobody would give me a chance.”

This resonated with Tennenbaum. He had benefited from his own share of second chances over the years. And so he agreed to give Epstein one as well.

It was perhaps the first example of Epstein getting caught cheating — and then avoiding punishment thanks to his uncanny ability to take advantage of those in positions of power. This would become a lifelong pattern, one that largely explains Epstein’s remarkable success at amassing wealth and, eventually, orchestrating a vast sex-trafficking operation.

Nearly five decades later, and more than six years after his death, Epstein has become an American obsession. The public fascination only intensified after President Trump initially refused this year to release federal investigative records about the infamous sex offender — before reversing himself under pressure.

Much of the last quarter-century of Epstein’s life has been carefully examined — including how, in the 1990s and early 2000s, he amassed hundreds of millions of dollars through his work for the retail tycoon Leslie Wexner. Yet the public understanding of Epstein’s early ascent has been shrouded in mystery. How did a college dropout from Brooklyn claw his way from the front of a high school classroom to the pinnacle of American finance, politics and society? How did Epstein go from nearly being fired at Bear Stearns to managing the wealth of billionaires? What were the origins of his own fortune?

We have spent months trying to pierce this veil. We spoke with dozens of Epstein’s former colleagues, friends, girlfriends, business partners and financial victims. Some agreed to speak on the record for the first time; others insisted on speaking confidentially but gave us access to never-before-seen records and other information. We sifted through private archives and tracked down previously unpublished recordings and transcripts of old interviews — including one in which Epstein gave a meandering account of his personal and professional history. We perused diaries, letters, emails and photo albums, including some that belonged to Epstein. We reviewed thousands of pages of court and government records.

What emerged is the fullest portrait to date of one of the world’s most notorious criminals — a narrative that differs in important respects from previously published accounts of Epstein’s rise, including his arrival at Bear Stearns.

In his first two decades of business, we found that Epstein was less a financial genius than a prodigious manipulator and liar. Abundant conspiracy theories hold that Epstein worked for spy services or ran a lucrative blackmail operation, but we found a more prosaic explanation for how he built a fortune. A relentless scammer, he abused expense accounts, engineered inside deals and demonstrated a remarkable knack for separating seemingly sophisticated investors and businessmen from their money. He started small, testing his tactics and seeing what he could get away with. His early successes laid the foundation for more ambitious ploys down the road. Again and again, he proved willing to operate on the edge of criminality and burn bridges in his pursuit of wealth and power.

Rung by rung, Epstein climbed a social and financial ladder, often using young women as a potent form of currency. His girlfriends, lovers and even exes helped elevate his status inside a bank, got him hired to track down missing assets and gained him entree to prestigious organizations. And deliberately or not, some of them enabled him as he constructed a sex-trafficking operation that would later ensnare hundreds of teenage girls and young women.

That story starts at Bear Stearns, the place where Epstein learned how to win and use power. The institution continued to enable him long after he had shown his true colors.

More than four decades later, Tennenbaum still regrets that he didn’t end Epstein’s career when he had the chance.

“I didn’t realize,” he said, “that I was creating one of the monsters of Wall Street.”

‘Deeply offended’ by an internal investigation

Having been let off the hook, Epstein was looking at a bright future. In 1980, Bear Stearns named him a limited partner — one rung below a full partner — and Epstein, who was 27 at the time, claimed that he was the youngest in the firm’s history to join the partnership. He was pulling in about $200,000 a year (more than $800,000 in today’s dollars). By then, Epstein’s dalliance with Greenberg’s daughter had fizzled — she told us that she learned that Epstein “lied about everything” — but his renown was growing.

He was regularly flying to Palm Beach, Fla., to visit young women. That summer, Cosmopolitan named Epstein its “bachelor of the month,” describing him as a “dynamo” who “talks only to people who make over a million a year!” The magazine encouraged interested parties to write to Epstein at his work address.

One secret to Epstein’s early success was his close relationship with Jimmy Cayne, a senior executive who would one day run Bear Stearns. Rumors, perhaps fueled by envy, began to spread that Epstein was helping Cayne, who died in 2021, to pursue women and score drugs, according to several of their colleagues. Cayne raved to colleagues about Epstein and began introducing him to some of his most lucrative clients.

“That’s what really catapulted him,” Tennenbaum recalled, describing Epstein and Cayne as “two sleazeballs.” Once or twice a week, Epstein would let it be known that he was having lunch with the chief executive of a major company — meetings apparently arranged by Cayne, said Elliot Wolk, who became Epstein’s boss after Tennenbaum. Wolk surmised that Epstein’s appeal to these clients was partly his charisma and partly his newfound understanding of complex trading strategies that could save ultrawealthy clients huge amounts in taxes.

Epstein was not content to simply climb the corporate ladder. In 1980, he flew on Bear Stearns’s dime to a conference in the Caribbean. While there, he spent more than $10,000 on jewelry and clothing for his latest girlfriend — and charged it to the firm. The accounting department noticed the payments and flagged them to the financial controller, who quickly concluded that the expenses were improper, according to a person with direct knowledge of what happened. The controller reported the matter to Greenberg, by then the chief executive. Once again, there were no consequences.

More serious trouble soon surfaced. When investment banks help companies go public, they can dole out shares to favored clients before the stock begins trading on public exchanges. Getting early access is a lucrative privilege, because the value of the shares often spikes in the first hours of trading — yielding a fast, low-risk profit for those initial holders. Bear Stearns executives learned that Epstein was giving his girlfriend access to these “hot deals,” as several of his colleagues recounted to us.

The firm soon discovered yet another infraction: Epstein had lent $15,000 to a high school buddy in a manner that violated federal rules governing brokers. And there might have been more: The Securities and Exchange Commission would soon conduct an insider-trading investigation into well-timed trades before an attempted corporate takeover; the S.E.C. interviewed Epstein, though he was never accused of wrongdoing.

In early 1981, Bear Stearns began investigating Epstein, and two senior executives interrogated him about the girlfriend’s I.P.O. shares and the personal loan. Epstein denied wrongdoing — and was “deeply offended” by the investigation, as he later put it in a letter to his colleagues. The firm’s executive committee decided to fine him $2,500 and suspend him for two months, according to a note we reviewed that was sent to employees by the firm’s leaders. Rather than accept this indignity, Epstein announced that he was resigning.

His five-year tenure at Bear Stearns was over, but Epstein didn’t intend to slink away from Wall Street. The connections and credentials he had collected at the firm would prove indispensable as he sought to lure clients and financial victims. By giving Epstein second chances, Bear Stearns paved the way for a future that would far exceed anything that would have been possible if he had stayed at the firm. Rather than shunning their ousted colleague, employees would embrace Epstein and help him prosper.

A $450,000 oil scam

One of the Bear Stearns contacts who would prove invaluable to Epstein was a junior saleswoman — and former Miss Indianapolis — named Paula Heil. She would expose Epstein to a previously unseen world of wealth, privilege and possibilities.

They started dating before he left Bear Stearns; we tracked down a financial self-help book Heil wrote in 1981 that was dedicated “to Jeffrey.” That year, the couple traveled to England. While they were there, Heil took Epstein to visit a rich acquaintance of hers, Nick Leese, at his family’s countryside manor. There they met Nick’s father, Douglas Leese, a defense contractor with extensive connections in the arms industry and the British government. He took an immediate liking to Epstein.

Soon Epstein was making regular trips to England and spending time in the Leeses’ rarefied world. Epstein tutored Douglas’s younger son, Julian, and Julian taught him to shoot. Douglas mentored Epstein, let him tag along for meetings with British and international elites and took him on as a consultant with an expense account. Nick, meanwhile, introduced Epstein to up-and-coming Wall Streeters, according to one, who recalls Epstein sitting quietly by himself during a small gathering at a friend’s apartment in the early 1980s. “He looked like someone who was taking notes in the corner,” he told us. Epstein was “part of the family,” Julian later told Tom Pattinson, a British journalist who shared the unpublished interview transcript with us. (Julian died in 2024.)

It was perhaps Epstein’s first close experience with true generational wealth, and he liked the taste enough to help himself to more. The relationship ended a couple of years later when Douglas Leese accused Epstein of abusing his expense account by charging personal flights on the Concorde and stays at luxury hotels. “He was very cross and upset about it,” Julian said of his father. “And he said he didn’t want to have any more to do with Jeffrey.”

Epstein had been spending extravagantly, and despite his lofty compensation at Bear Stearns and his work for Leese, he found himself strapped, even occasionally bouncing rent checks. Back in New York, he joined forces with John Stanley Pottinger, a lawyer who had recently left a senior post in the Justice Department. Epstein, Pottinger and Pottinger’s brother rented a penthouse in the Hotel St. Moritz on Central Park South. (The broker, Joanna Cutler, told us that Epstein initially stiffed her on the commission.)

According to Epstein’s friend Bob Gold, Epstein and the Pottingers pitched tax-avoidance strategies to wealthy clients, including some whom Gold believes Epstein met through Bear Stearns. The short-lived business partnership has not previously been reported — and is especially notable because decades later Pottinger would team up with Brad Edwards to represent scores of women who accused Epstein of sexually abusing them. (Edwards told us he knew only that Pottinger and Epstein briefly shared an office, not that they were in business together. Pottinger would later say he met Epstein through a client.)

Epstein continued to take advantage of his past affiliation with Bear Stearns, despite having left the firm under a cloud of suspicion. He surprised an acquaintance by answering his home phone, where he took some business calls, by saying, “Bear Stearns.”

And some of Epstein’s former colleagues at the firm saw fit to maintain friendships with him — friendships that would prove extraordinarily profitable for Epstein. One was Clark Schubach, who had been one of Epstein’s managers. Speaking publicly for the first time, Schubach told us he has fond memories of Epstein, who struck him as an outer-borough striver — just like Schubach, who grew up in the Bronx.

In 1982, he introduced Epstein to Michael Stroll, who ran a pinball and video-game company. Stroll trusted Bear Stearns and Schubach. He gave Epstein $450,000 — about 10 percent of his net worth — to invest in a supposed crude-oil deal that Epstein told him he was planning.

Within two years, most of the money had vanished, Stroll later said in an unpublished interview with Thomas Volscho, a professor at the College of Staten Island who has spent years researching Epstein’s early years and shared some of his notes and documents with us. Epstein began dodging Stroll’s phone calls; at one point, he sent Stroll a quart of oil in an attempt to convince him that a deal was, in fact, in the works. The dispute ended up in civil court, with Stroll arguing that Epstein had promised to return his money but never did. In 1993, Epstein prevailed on technical grounds, and a judge ruled that he wasn’t personally liable. Decades later, Stroll remains bitter. “He’s a despicable prick,” he told us.

The Stroll scam marked a turning point for Epstein. He had already shown himself capable of betraying friends and patrons who trusted him, but now he had advanced from the flagrant abuse of expense accounts to apparently absconding with hundreds of thousands of dollars. Stroll would later lament to Volscho: “I unknowingly seeded his growth.”

Bounty hunting in the Cayman Islands

During his time with the Leese family, Epstein liked to tell people that he was a “bounty hunter” who tracked down hidden money. The Leeses had rolled their eyes — Epstein seemed to enjoy cultivating an air of mystery — but soon enough he would be able to make good on that boast.

Around 1982, a mutual acquaintance introduced Epstein to Ana Obregón, a young Spanish socialite and actress. On their first date, he sped her around Manhattan in a Rolls-Royce. She was mesmerized by his charm and looks but ultimately just wanted to be friends; in her 2012 memoir, after Epstein had been designated a sex offender, she described him as “the perfect man I never fell in love with.”

Even as Epstein was romancing Obregón, he had a serious girlfriend: Eva Andersson, a model and former Miss Sweden. They began dating soon after she moved to New York from a small town in her native country, and many of Epstein’s friends and acquaintances have said she was the love of his life.

But that didn’t stop him from pursuing other women — especially those with money or connections. During his fling with Obregón, the brokerage firm Drysdale Securities imploded. The Obregóns, along with a handful of other wealthy Spanish families, soon hired Epstein to help track down their missing millions. Now he really was a bounty hunter.

Epstein brought on his friend Bob Gold, a former federal prosecutor, as his wingman. Gold told us they spent more than a year trying to find the missing assets, which Drysdale had apparently hidden through a byzantine network of offshore banks and shell companies. They narrowed down the list of banks where the money might be stashed but eventually hit a wall.

Then one day in 1984, Gold went to Epstein’s apartment and found him playing a Rachmaninoff concerto on the piano. All of a sudden, Gold says, Epstein began riffling through a stack of documents and announced that he had solved the mystery: The clients’ funds had ended up at a Canadian bank’s branch in the Cayman Islands. To this day, Gold says, he isn’t sure how Epstein figured it out. He and Epstein chartered a Lear jet and showed up at the bank. Gold warned a bank manager that he could be in legal jeopardy if he didn’t hand over millions of dollars’ worth of bond certificates. Gold and Epstein returned to the United States with the securities. (Gold says he and Epstein later drifted apart.)

Epstein benefited handsomely from his efforts. Coupled with the fruits of his Stroll scam, the payday meant Epstein had almost certainly surpassed an impressive milestone: He was a millionaire.

‘You are someone that’s going to help me get where I want to go’

By the mid-1980s, Epstein had re-established himself at Bear Stearns, now as a valued client. He was routinely calling his former manager, Schubach, to place orders to buy or sell stocks, bonds and options. The firm earned commissions on Epstein’s trades and therefore had an incentive to keep him happy.

.css-1mxer6r{max-width:600px;width:calc(100% – 40px);margin:1.5rem auto 1.75rem;height:auto;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-family:nyt-franklin;color:var(–color-content-secondary,#363636);border-top:1px solid var(–color-stroke-quaternary,#DFDFDF);border-bottom:1px solid var(–color-stroke-quaternary,#DFDFDF);padding-top:20px;padding-bottom:20px;}@media only screen and (min-width:1024px){.css-1mxer6r{width:600px;}}.css-1medn6k{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-weight:500;font-size:1.0625rem;line-height:1.5rem;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-1medn6k{font-size:1rem;line-height:1.375rem;}}.css-1f84s5v{font-weight:700;font-size:1.0625rem;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-1f84s5v{font-size:1rem;}}.css-1f84s5v a{color:var(–color-signal-editorial,#326891);-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.css-1f84s5v a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}.css-1hvpcve{font-size:17px;font-weight:300;line-height:25px;}.css-1hvpcve em{font-style:italic;}.css-1hvpcve strong{font-weight:bold;}.css-1hvpcve a{font-weight:500;color:var(–color-content-secondary,#363636);}.css-214jt4{margin-top:15px;margin-bottom:9px;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-214jt4{font-size:14px;margin-top:15px;margin-bottom:10px;}}.css-214jt4 a{color:var(–color-signal-editorial,#326891);-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;font-weight:500;font-size:16px;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-214jt4 a{font-size:13px;}}.css-214jt4 a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}.css-1mxer6r{max-width:600px;width:calc(100% – 40px);margin:1.5rem auto 1.75rem;height:auto;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;font-family:nyt-franklin;color:var(–color-content-secondary,#363636);border-top:1px solid var(–color-stroke-quaternary,#DFDFDF);border-bottom:1px solid var(–color-stroke-quaternary,#DFDFDF);padding-top:20px;padding-bottom:20px;}@media only screen and (min-width:1024px){.css-1mxer6r{width:600px;}}.css-1medn6k{font-family:nyt-franklin,helvetica,arial,sans-serif;font-weight:500;font-size:1.0625rem;line-height:1.5rem;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-1medn6k{font-size:1rem;line-height:1.375rem;}}.css-1f84s5v{font-weight:700;font-size:1.0625rem;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-1f84s5v{font-size:1rem;}}.css-1f84s5v a{color:var(–color-signal-editorial,#326891);-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.css-1f84s5v a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}.css-1hvpcve{font-size:17px;font-weight:300;line-height:25px;}.css-1hvpcve em{font-style:italic;}.css-1hvpcve strong{font-weight:bold;}.css-1hvpcve a{font-weight:500;color:var(–color-content-secondary,#363636);}.css-214jt4{margin-top:15px;margin-bottom:9px;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-214jt4{font-size:14px;margin-top:15px;margin-bottom:10px;}}.css-214jt4 a{color:var(–color-signal-editorial,#326891);-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;font-weight:500;font-size:16px;}@media only screen and (max-width:480px){.css-214jt4 a{font-size:13px;}}.css-214jt4 a:hover{-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;}

Got a confidential news tip? The New York Times would like to hear from readers who want to share messages and materials with our journalists.

See how to send a secure message at nytimes.com/tips

In 1986, Schubach hired a petite 23-year-old named Patricia Schmidt to be his assistant. She told us that her main job was to be “eye candy,” but her other duties included answering the phones. That put her in regular contact with Epstein.

One evening, Schubach, who was a senior managing director, asked her to deliver a sheaf of papers to Epstein at his apartment in the Solow Tower, a gleaming black-glass building on the Upper East Side. Epstein welcomed her in, made her tea and invited her to come back anytime to use the building’s rooftop pool. Schmidt suspected that she was dispatched to Epstein because she was an attractive young woman. “Clark knew exactly what he was doing sending me to Jeff’s apartment,” she told us. “I was his leverage to Jeff.”

A week or so later, Schmidt took Epstein up on the offer. A doorman let her in, and she went straight to the pool. After she swam for a bit, Epstein arrived at the pool to say hi. He suggested that she check out the sauna. When he followed her in, Schmidt was surprised but not dismayed. He asked if he could give her a massage. Schmidt said yes. It was the beginning of a sexual relationship, which Schmidt chronicled in her diary and until now had remained secret.

Epstein saw that Schmidt had potential to further his own ends. He routinely asked her to go to the Bear Stearns library and research his prospective clients. He had her give his clients and acquaintances tours of Bear Stearns or escort them to dinner. Schmidt understood what was going on. “It was always about getting him in a position of leverage,” she said. “I was his plaything. It was like, ‘You are someone that’s going to help me get where I want to go.’”

Schmidt wasn’t the only young assistant Schubach delivered to Epstein. In a bawdy book compiled to celebrate his 50th birthday in 2003, another woman who worked at Bear Stearns wrote about how Schubach took her to Epstein’s apartment and then left — at which point Epstein blurted out, “You are a virgin, right?” The letter goes on to describe Epstein, on a different occasion, tickling and kissing her, and the entry includes a photo of her in a thong.

The woman’s name was redacted by the congressional committee that released the birthday book. But we reviewed an unredacted page of the book’s table of contents. The woman’s name was Suzanne Ircha. She had just graduated from college when she met Epstein. (In the early 1990s, when Ircha was trying to start a Hollywood career, she turned to Epstein for a loan, according to notes taken by one of Epstein’s assistants that we reviewed.) Ircha would become a close friend of Melania Trump’s and would marry Woody Johnson, the owner of the New York Jets and an heir to the Johnson & Johnson fortune, whom Trump named as ambassador to Britain in his first term.

Schubach acknowledged to us that he sent a few young female colleagues Epstein’s way over the years. “I liked the guy,” he said. “If there was a single girl who he might have liked, did I introduce them? Sure.”

A toehold in America’s most exclusive social scene

One sign of Epstein’s remarkable ascent was the place where he spent his days working. By 1987, he was operating out of the Villard Houses, a complex of 19th-century mansions on Madison Avenue that had been converted into luxury apartments and offices. It was a venue befitting the era’s highest rollers, and Epstein aspired to join this crowd.

He had been put up in these plush surroundings by a new acquaintance, Steven Hoffenberg, who ran a debt-collection company, Towers Financial. Hoffenberg was also paying him about $25,000 a month (the equivalent of roughly $70,000 a month today) as a consultant. Epstein and Hoffenberg soon refashioned themselves as corporate-takeover specialists, trying unsuccessfully to buy iconic companies like Pan American World Airways.

To finance this attempted buyout blitz, Hoffenberg was constructing what turned out to be an elaborate Ponzi scheme that bilked investors out of nearly $500 million. Hoffenberg, who a decade later would be sentenced to 20 years in prison, claimed in court and in interviews that Epstein helped orchestrate the fraud. (Hoffenberg died in 2022.)

Epstein denied any involvement, but it is hard to believe he was in the dark about what was happening. In 1988, he contacted Julian Leese and offered him an internship at Towers. Despite his father’s enduring anger at Epstein, Leese accepted the gig.

His assignment was to help Towers raise money by selling what turned out to be fraudulent bonds to international investors. Leese said he introduced Hoffenberg to his father, who in turn introduced Hoffenberg to potential buyers of the bonds. Among the customers to whom Julian Leese sold the Towers securities were his godparents. “It was a disaster,” he recalled to Pattinson.

Epstein, meanwhile, began soliciting millions of dollars from other acquaintances, including Dick Snyder, the chief executive of Simon & Schuster, for what he suggested were win-win investment opportunities. In 1988, Epstein and a few other investors began buying shares of Pennwalt, a $1 billion chemical company. After publicly disclosing their stake, they announced that they were preparing a bid to buy all of Pennwalt for $100 a share — about 40 percent above where it was trading at the time.

Epstein and his partners didn’t appear to have any intention of actually buying the company. But Pennwalt’s stock shot higher in anticipation of a bidding war. Presto: They could sell the shares and secure a significant profit. And Epstein wasn’t shy about what he was doing. He befriended the journalist Edward Jay Epstein (no relation) and explained it to him in detail; Ed Epstein then wrote a column in Manhattan,inc. magazine in 1989 that outlined what was essentially legal market manipulation. (The column in the long-defunct magazine, which we found in the archives at Columbia University, didn’t name Epstein but described him as “a 36-year-old friend who prefers to remain nameless.” Ed Epstein died in 2024.)

But Epstein’s perfidy ran deeper. Ed Epstein discovered that dozens of the people Epstein recruited to invest in Pennwalt, including Snyder, had written to him demanding that he repay their money. In other words, Epstein had lured investors in, used their money to book big profits and then refused to return their funds. There is no record of Epstein facing any consequences — or repaying the money. A result was that by the end of 1988, he reported being worth about $15 million, according to a previously undisclosed document from a Swiss bank, which Thomas Volscho, the professor, shared with us.

Epstein seems to have had a keen sense of which benefactors he could quickly suck dry, leaving them angry and betrayed, and which were worth nurturing for the long haul as sources of connections and prestige. One of those was Sir James Goldsmith — a financier and European politician who was embedded in Manhattan’s upper crust. One evening, he hosted a gathering at his mansion on the Upper East Side. Among the guests was Stuart Pivar, who had amassed a fortune before becoming a renowned art collector. When Pivar arrived, he encountered Epstein playing a Beethoven sonata at a piano in Goldsmith’s spacious entrance hall. Pivar told us he was transfixed: Epstein had an irresistible “magnetism” — especially with “the beautiful daughters of famous, powerful men.”

Several years earlier, Pivar, Andy Warhol and others founded the New York Academy of Art, and in 1987 Epstein became a member of the organization’s board. It was the first time he had joined a prominent board, and it represented a big step toward his shedding his roots as a hungry P.S.D. He was already swanning around New York with beautiful women and raking in tens of thousands of dollars a month. Now he was beginning to ensconce himself in America’s most select social scene. (In later years, after he left the board, his affiliation with the academy would also help him draw at least one young woman into his web.)

Epstein’s colleagues on the board included his ex, now married and named Paula Heil Fisher, as well as a member of the Forbes family and Katie Ford, whose family ran the Ford modeling agency. Epstein only occasionally showed up at board meetings, according to records we reviewed from the academy’s archives, but he had numerous opportunities to network with the academy’s illustrious membership.

After Warhol died that year, the academy threw a $150-per-person black-tie fund-raiser in his honor featuring an art exhibition, a musical performance and a dinner of cold snapper in vodka sauce. Photographers captured Tony Bennett, Lynn Von Furstenberg and other stars and socialites arriving at the downtown party. The evening’s invitation listed the event’s co-chairmen, fixtures of New York’s arts and finance scenes.

The first name was Mr. Jeffrey E. Epstein.

A confidence man meets his most significant mark

A fateful flight to Florida that year would launch Epstein from a mere millionaire into a plutocrat with palatial estates, two private islands and luxury aircraft. The transformation came about through a new client: Les Wexner, the billionaire who built brands like the Limited and Victoria’s Secret. The two were introduced by Wexner’s friend Robert Meister, an insurance executive who happened to sit next to Epstein on the plane to Palm Beach. Meister suggested that Wexner get in touch with Epstein for financial advice.

Wexner soon had a financial adviser, Harold Levin, fly to New York to meet Epstein. Levin told us that he spent an hour with Epstein in his office and immediately got a bad vibe. He found a pay phone and called Wexner. “I smell a rat,” Levin reported. “I don’t trust him.”

Wexner apparently didn’t listen. About a year later, he hired Epstein to be Levin’s boss. As far as Levin could tell, Epstein won the billionaire’s confidence by falsely telling him that Levin had been stealing. Levin decided to quit rather than work for Epstein. Before long, Wexner had given Epstein essentially free rein by granting him power of attorney over his finances. Epstein’s name began appearing in government filings as responsible for Wexner’s businesses and charities. Some of Epstein’s phones had Wexner’s number on speed dial, according to photos we reviewed.

Almost immediately, Wexner’s colleagues grew alarmed by his embrace of Epstein. “I tried to find out how did he get from a high school math teacher to a private investment adviser,” the vice chairman of the Limited told The New York Times in 2019. “There was just nothing there.” A Limited board member eventually became so troubled by Epstein that he hired Kroll, the private investigations firm, to see what could be unearthed about his past, according to Ed Epstein. Even Meister realized he’d misjudged Epstein and urged Wexner to cut ties.

Once again, Wexner didn’t listen, and thus became the most important contributor to the staggering growth in Epstein’s fortune. One unsolved mystery of the Epstein era is what exactly Wexner got out of their relationship. He has repeatedly refused to answer questions, including ours. But Epstein’s modus operandi with other wealthy men — including the private-equity billionaire Leon Black — was to instill fear that their finances were a mess, that their advisers and even family members were inept or exploiting them and that only one man had the wherewithal to save them.

Epstein appeared to deploy that playbook with Wexner — and to reward himself lavishly. He seemed to be taking whatever he thought he deserved from Wexner’s accounts, according to people who later learned what Epstein was doing. The amounts were often measured in the tens of millions.

He bought a waterfront mansion in Palm Beach for $2.5 million, about a mile from Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate. Epstein and Trump had become pals in New York, and Epstein was a regular at Trump’s Atlantic City casino; a former executive there recently told CNN that the two men seemed to be best friends. In Florida, Epstein began hanging out at Mar-a-Lago, attending parties featuring N.F.L. cheerleaders and “calendar girl” contestants.

He bought another mansion, on 30 acres in New Albany, Ohio, where Wexner was building an enormous real estate development. He ditched his one-bedroom in the Solow Tower and began leasing a grand marble townhouse on the Upper East Side — the former residence of Iran’s deputy general consul — for $15,000 a month. (According to lawsuits that we reviewed, the owner of the Solow building sued Epstein for not paying rent. The townhouse’s owner — the U.S. government — sued him for illegally subletting. The owner of the Villard Houses, where he by now leased his own office, made similar accusations.)

Epstein cruised around Manhattan in a Rolls-Royce Silver Spirit. He began donating thousands to politicians — and developing relationships with them. In 1989, Epstein accompanied Wayne Owens, a Democratic congressman from Utah, on a trip to the Middle East to explore ways to promote business ties between Israel and its neighbors. Epstein apparently was invited in his capacity as a finance expert, but he struck participants as out of his depth and bored.

Dan Gordon, a screenwriter who was part of the entourage, says he warned Owens that Epstein was showing disrespect by his slovenly attire in meetings with Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu and Shimon Peres and Saudi Arabia’s crown prince at the time, Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud — the types of connections that Epstein would cultivate in the years ahead. One of Owens’s aides, Michael Yeager, recalled Epstein boasting about his Indiana Jones-like pursuit of hidden assets and his close ties to Wexner.

Aside from the money, Wexner’s greatest value to Epstein was that he imbued him with new credibility and credentials. In 1989, Ken Lipper, a prominent fund manager, was standing in a ski-lift line in Aspen, Colo., when a stranger approached him. It was Epstein. He said he worked for Wexner, who wanted to invite Lipper to a party in Aspen. Lipper, according to the person who recounted this to us, had no idea how Epstein, who was traipsing through the snow on foot, had tracked him down. But Wexner was a billionaire, and so Lipper attended the party and then met privately with Epstein, who put millions of Wexner’s dollars into one of Lipper’s funds. In a previously unreported act of dishonesty, Epstein later claimed on a regulatory filing that he was employed by that Lipper fund.

Epstein also posed as a Victoria’s Secret talent scout, prompting more executives to complain to Wexner about his conduct, to no avail. He began citing his work for Wexner to prove his bona fides to banks, regulators and journalists. For most of his life, Wexner would be his only publicly known client.

A new girlfriend, and enabler, arrives

Epstein was about to meet someone who would usher him into even more elite circles while also playing a central role in his darkest crimes. His nearly decadelong romance with Eva Andersson came to an end around 1990. In Epstein’s telling, the split was the result of a mutual realization that his future did not include “staying in one place and having a family.” The two remained close until Epstein’s death.

Shortly after their breakup, Epstein was introduced to Ghislaine Maxwell, the daughter of the British media baron Robert Maxwell. Their first get-together, arranged by a mutual friend, was at Epstein’s office at the Villard Houses, she has said. When the domineering Robert Maxwell learned that his daughter was spending time with Epstein, he contacted Ace Greenberg and Jimmy Cayne, both of whom he was close to, to see what they knew about their former Bear Stearns employee. Greenberg and Cayne apparently vouched for Epstein.

That November, Robert Maxwell died suddenly as his business unraveled. Ghislaine Maxwell flew to New York, distraught and short on cash. Epstein came to her aid, financially and socially. When a memorial event was held for her father at the Plaza Hotel — owned at the time by Trump — Epstein sat next to Maxwell, him in white tie, her in shimmery blue. By 1992, they were an item.

It was around this time that Epstein apparently began grooming and abusing hundreds of teenage girls and young women. Maxwell was later convicted of playing a central role in his sex-trafficking operation and is serving a 20-year prison sentence. She recently told Todd Blanche, the deputy attorney general (and Trump’s former personal lawyer), that Epstein was her “lifeline.”

His friends told us that Maxwell tried to train him on social niceties, on what to wear, on how to act like an aristocrat. Not all the lessons took, but with her roster of glamorous connections, Epstein became even more of a staple of Manhattan’s exclusive social scene.

At one elegant soiree, he met the ABC News journalist Catherine Crier and held forth about the scientists he knew. Crier told us that, a few months later, she and Epstein attended a movie screening at the Plaza. As guests milled around in formal wear, Epstein stood out in a white T-shirt. At the event, Crier introduced him to her friend Elliot Stein, a prominent investment banker. Stein later connected Epstein with Leon Black, who would ultimately replace Wexner as Epstein’s most lucrative client. This was Epstein at his most productive, leveraging one relationship to create another, over and over and over.

While he was dating Maxwell, Epstein continued to see other young women — and to flaunt them with powerful men. One of them was Stacey Williams, a former Sports Illustrated swimsuit model, whom he met at a Christmas party that Trump threw at the Plaza. In 1993, Epstein took Williams by Trump Tower. Williams has said that Trump groped her and that Epstein later chastised her for letting it happen. (Trump has denied it.)

As Wexner prepared to wed the lawyer Abigail Koppel, Epstein helped prepare a prenuptial agreement to protect the billionaire’s assets. Williams told us that when the time came to sign it in January 1993, Epstein instructed her to deliver the document to Wexner’s office in a sexy outfit, along with a joking message: Was he sure he wanted to get married? Williams says she felt uncomfortable about being wedged into Wexner’s affairs, but she grudgingly delivered the agreement, without complying with the wardrobe request.

Using donations to reach the Clintons and Rockefellers

On a freezing Thursday in February 1993, Epstein and Wexner arrived at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington. Just weeks earlier, Bill Clinton had been sworn in as the 42nd president. It was the first of many visits Epstein would pay to the Clinton White House.

Epstein had become a political donor — including, later that year, $10,000 to help refurbish the White House, earning him a spot at a reception with the Clintons — and that gave him a certain amount of cachet with the new president. But Epstein had something else going for him as well: a new connection named Lynn Forester.

Forester told us that she met Epstein at a reception for George Mitchell, the Senate majority leader, whom Epstein had befriended. Forester was a successful telecommunications executive, but she rose to greater prominence through her marriage to Andrew Stein, the Manhattan politician who in 1993 ran unsuccessfully for New York City mayor. The end of his mayoral campaign coincided with the end of their 10-year marriage. Now Forester and Stein were feuding over how to divvy up millions of dollars, and Epstein apparently convinced Forester that he could protect her from getting ripped off. It was a version of the same tactic he used to get in Wexner’s good graces years earlier.

A source told us that Epstein called one of Stein’s lawyers, claimed that Forester had empowered him to negotiate on her behalf and demanded that Forester, as the couple’s primary breadwinner, walk away with a greater share of the assets. (Forester told us she has “no idea” whom Epstein contacted, nor “why he thought he was empowered to do anything on my behalf.”)

It was an opportune moment for Epstein to ingratiate himself with Forester, whom Clinton had appointed to a White House advisory commission. On at least one occasion, Forester brought up Epstein in a brief private conversation with the president, according a letter, first reported by The Daily Beast, that she wrote that mentioned Epstein. He became a regular visitor to the White House, sometimes with a girlfriend in tow, according to records housed at Clinton’s presidential library. (Forester says she has “no recollection of having anything to do with Epstein and the White House.” She says she cut ties with him in 2000, after he deceived her on a property transaction. “I was a very small part of Epstein’s life, and he was a blip on mine,” she said.)

By 1995, Clinton and Epstein were sufficiently chummy that he wrote a get-well-soon note to Epstein’s ailing mother. “Hang in there,” the president scrawled on a yellow Post-it, which Epstein saved and we reviewed. (“The president knew nothing about this guy,” said Angel Urena, a spokesman for Clinton. “Nobody did.”)

Around the same time, Epstein began developing relationships with the scions of two of America’s wealthiest families.

One was Libet Johnson, Woody Johnson’s sister and also heir to the Johnson & Johnson fortune. Epstein oversaw a trust that held some of her land, and Maxwell told Blanche that Epstein in the mid-1990s provided Johnson with the same sorts of services that he offered Wexner. In 1994, Johnson gave more than $2 million to his J. Epstein Foundation, according to filings we found in Indiana University Indianapolis’s repository of old charitable records.

Epstein used the foundation to procure access to prestigious organizations and influential people — including David Rockefeller, the heir to the industrial fortune. Soon after the foundation was established in the early 1990s, it began donating tens of thousands of dollars to Rockefeller University, a prestigious research institution, and the Trilateral Commission, which Rockefeller had established as a forum for some of the world’s most powerful figures to discuss global problems.

The donations appeared to have their desired effect. In 1995, Rockefeller welcomed Epstein to the board of Rockefeller University, according to prepared remarks we found in his family’s archive. Around then, Epstein hosted Rockefeller at his Manhattan mansion to discuss with a small group of wealthy people how to best pass on money and values to younger generations, according to someone who was there. Epstein also became a member of the Trilateral Commission. A program for a dinner in 1998 celebrating the commission’s 25th anniversary noted the evening’s participants, including Epstein and Forester, who were listed as a pair. (Forester said she didn’t recall attending.)

Henceforth, Epstein would relentlessly cite his Rockefeller connections, even claiming that he managed money for the dynastic family. A person who was close to Rockefeller and helped manage his money told us that this was not true. Epstein, he said, didn’t even pitch Rockefeller on any investments.

Epstein was also beginning to dole out money to Harvard University, where he was keen to cultivate connections with high-profile academics. One of those was the law professor Alan Dershowitz. In the summer of 1996, Dershowitz was at his house on Martha’s Vineyard when he got a call from Forester. She was on the Vineyard with Epstein, who she said was a Harvard donor and wanted to meet Dershowitz.

Dershowitz told us that Epstein showed up at his Chilmark home later that day toting vintage Champagne. The pair took a walk around a nearby pond, and Epstein, the inveterate name-dropper, informed Dershowitz that he was close with Harvard figures, including Larry Summers, an economics professor then serving in the Clinton administration. But the main topic was Wexner, whom Epstein said had taught him “how to be rich.” Wexner’s birthday was approaching, and Epstein wanted Dershowitz to attend a dinner in his honor. Dershowitz ended up flying to Ohio on one of Epstein’s planes along with Senator John Glenn. Shimon Peres — the recent Israeli prime minister, whom Epstein met years earlier during the Middle East trip with Representative Owens — was among the other dinner guests. (The following year, Forester hosted a party on Martha’s Vineyard where Epstein mingled with guests including Dershowitz and Britain’s Prince Andrew.)

The year after meeting Epstein, Dershowitz wrote an opinion piece for The Los Angeles Times arguing that the age of sexual consent should be lowered to 15. Epstein seemed to see the potential of nurturing a relationship with the prominent lawyer. He introduced Dershowitz to Jimmy Cayne so that Bear Stearns could manage his money. And he persuaded the investor Orin Kramer, whose hedge fund already held tens of millions of Wexner’s dollars, to let Dershowitz invest, too.

But Kramer’s hedge fund soon suffered calamitous losses, and Dershowitz’s six-figure investment was annihilated. Epstein demanded that Kramer make Dershowitz whole and threatened to make his life miserable if he refused. They eventually negotiated a compromise: Kramer would refund Dershowitz’s investment if Epstein agreed to keep at least $30 million of Wexner’s money in the struggling hedge fund. As a result, Kramer would receive enough fees from Wexner to cover the cost of reimbursing Dershowitz.

Keeping Dershowitz happy proved prescient. He would become one of Epstein’s highest-profile and longest-serving defenders. In 2005, the parents of a 14-year-old girl in Palm Beach told the police that Epstein had sexually abused her; that led to state and federal criminal investigations. Dershowitz and other lawyers engineered a sweetheart deal in which Epstein escaped federal prosecution, pleaded guilty in Florida to soliciting prostitution from a minor and received a light jail sentence. (He also had to register as a sex offender.)

Presumably without intending to, Wexner had subsidized Epstein’s long-term and fruitful cultivation of Dershowitz.

‘I told you I would make it very big’

In 1999, Julian Leese knocked on the imposing wooden door of Epstein’s Manhattan townhouse. It had been years since he’d last seen Epstein, when Leese interned for Towers and lost his godparents’ money, and even longer since Leese and his family taught a young Epstein to shoot and to mix with aristocrats shortly after his departure from Bear Stearns. As Leese recounted to the journalist Tom Pattinson for a podcast, he had let Epstein know he would be in town, and Epstein, now 46, invited him to his Upper East Side residence for tea.

A butler waved him inside. Soon Epstein descended the sweeping staircase. “My boy,” he declared, “I told you I would make it very big.”

There was no doubt about that: Epstein was fantastically wealthy. His company’s financial documents around then indicated that he was worth more than $100 million — an amount that would grow substantially in the years ahead. Much of that appeared to have flowed to Epstein from Wexner, who would later claim that he “had misappropriated vast sums of money.”

Bear Stearns remained his preferred Wall Street brokerage firm, but he was on his way to becoming a coveted client of JPMorgan Chase, whose chairman was impressed by Epstein’s claim that he managed money for David Rockefeller. Until 2013, as we reported this year, JPMorgan would provide Epstein with an array of services that enabled his sex-trafficking operation.

Epstein had by now amassed a huge real estate portfolio — including Little St. James, an island off the southeastern coast of St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Epstein and a rotating cast of his victims and celebrity guests moved among his properties on a fleet of private aircraft.

Epstein’s pace of raping, abusing and trafficking girls and young women was accelerating. Ultimately, he would face accusations from hundreds of women. Little St. James was an ideal, out-of-the-way venue for his crimes.

But there was something else that was attractive about Little St. James. The U.S. Virgin Islands was an unusually welcoming place for Epstein to do business. The territory’s law enforcement and financial regulations were notoriously lax, its politicians acquiescent. And the islands had created a series of generous tax incentives to lure businesses from the mainland.

Epstein applied for one of those breaks, which would enable his main company, Financial Trust, to avoid most taxes — a potential savings of tens of millions of dollars a year.

On a balmy afternoon in April 1999, Epstein appeared at a hearing before the Industrial Development Commission, which would consider (and ultimately approve) his application.

To vouch for his character, Epstein had turned to Harry Loy Anderson Jr., the president of the Palm Beach National Bank & Trust Company, where Epstein had held accounts since the early 1990s. Anderson — whose daughter is now dating Donald Trump Jr. — wrote a letter stating that Epstein was “a gentleman of the highest integrity” and that he “enjoys an excellent reputation in our community.” (Epstein’s house manager later said in a deposition that he was using Anderson’s bank to pay some of Epstein’s victims.) The letter, not previously reported, was submitted to the development commission and was obtained by the journalist Wayne Barrett; we found it in his archives at the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas, Austin.

In the hearing room, Epstein unspooled a fantastical version of his life story, according to a transcript of the meeting that we obtained from the U.S. Virgin Islands. He had willingly left a job at Bear Stearns to become “a financial doctor” to the wealthy. One of those clients, Wexner, had helped develop his “sense of integrity.” He’d later grown close to the Rockefeller family, advising them “on certain financial issues.”

By the end, the commission’s members and staff were eating out of his hands, joining the long list of people and institutions who, knowingly or not, would become Epstein’s enablers. One seemed to be fishing for stock tips. Others jostled for him to locate his company on their islands in the territory. Another asked if Epstein would consider teaching a course at the local university. “I’d love to,” Epstein replied. “As I said outside this room, I believe that the future of the Virgin Islands is really with the young people.”

And he thought he had something to teach them. One of his classroom priorities, he mused, would be to educate them on “the ethics of business — which is very difficult nowadays.”

Nicholas Confessore, Julie Tate and Susan C. Beachy contributed reporting and research.

Source photos for graphics: Getty Images; Patricia Schmidt; Schubach family.

The post Scams, Schemes, Ruthless Cons: The Untold Story of How Jeffrey Epstein Got Rich appeared first on New York Times.