It was easy to contrast the personalities of Rob Reiner and his son Nick.

The father, gregarious and charismatic, was a natural at repartee. Passionate about his political convictions, he was self-assured, even voluble, sometimes commandeering a dinner party discussion.

His son tended to be introverted, quieter. At social affairs, he contributed tidbits of conversation, but appeared unsure of himself and more comfortable shrinking into the background.

But the two shared a sense of humor and both could be contemplative and sensitive. And, after years of a relationship fraught with mistrust, they hoped somehow to reconnect.

It was 2015, and Nick had co-written a script loosely based on his experiences with addiction and numerous stints in rehab, a tumultuous journey that had begun seven years earlier. Rob, a director for three decades who had made iconic films like “When Harry Met Sally” and “The Princess Bride,” saw, if not a hit, at the very least an opportunity to bond. And so, he started preproduction on “Being Charlie,” beginning an experience that would put Rob and Nick’s own complicated relationship on display.

It wasn’t the first time Rob had been inspired by his son. Once, when Nick was 11, he eagerly brought a book home from school. “Dad, let’s read this together,” he said. It was the young adult novel “Flipped,” and Rob soon turned it into a film.

But Nick’s descent into heroin and cocaine addiction, during which he was sometimes homeless, had created a chasm in the family, one that his sobriety could not heal. Rob and his wife, Michele, often blamed themselves, harboring regret for taking the advice of experts who pushed tough love.

Backing Nick’s script was a chance for Rob to show that he was finally listening — a motive for directing the film that he did not hide.

“‘Being Charlie’ was a passion project for Rob, and he made that movie for his son is all I can tell you,” Charles Berg, one of the film’s producers, said. “That was his gift back to the world — to acknowledge his son, to say, ‘I love you, and I want to share your story.’”

The film’s budget was about $3 million and shooting began that April in Salt Lake City. Cast and crew members were highly cognizant of the earnest tenor of the undertaking. Michele, a photographer and a steady presence on Rob’s sets, also staunchly supported the film, even insisting that the home of the main character, who was based on Nick, more accurately reflect her own house.

“It felt very personal, and it felt very intimate,” said Blythe Frank, an executive producer on the movie. “Everybody was invested in what was a kind of family project.”

Ms. Frank said it was clear that Rob hoped to help give his son a voice.

“I think he was really trying to understand him,” she said. “He was trying to bring him into the fold, give him an opportunity.”

At the same time, it was no secret that Rob and Nick were still reckoning with who they were to each other, a dynamic that played out in full view when the two would butt heads on set.

Before filming one scene at a halfway house, Rob appeared fed up with Nick’s surly attitude, and the two got into an argument in front of about a dozen people, recalled Erik Aude, a stuntman who was on set that day.

“Nick was yelling, and his dad’s going off on him,” Mr. Aude said. “It was uncomfortable. It wasn’t something you want to stay in the room for. Honestly, you knew they were father and son because those are normal reactions, but they had no problem doing this in front of everyone.”

The disagreements tended to be about a difference in vision and wanting to get it right. But they would dissipate and Rob would take Nick to lunch, usually with the movie’s stars, Nick Robinson and Morgan Saylor.

Rob was also intent on shining a spotlight on his son throughout filming, going out of his way to defer to him on decisions or to champion and protect his screenplay.

Andy Fernuik, who played Thaniel, one of the men in rehab, recalled a scene in which, at the end of a scripted line, he threw in an extra couple words of slang. His co-stars laughed. But Rob grew irate.

“He started yelling at me, ‘No, you will not say that line any other way than how it’s written,’” Mr. Fernuik said.

Later, however, when no one was around, Rob came up to him with a grin and heartily shook his hand. It became a pattern: Rob’s public displeasure followed by an assurance of a job well done.

“The more it went on, the more I understood it was because he was doing everything to show his son how much he was going to shine,” Mr. Fernuik said.

Many times, however, it seemed as if Nick preferred not to take the reins from his father. He was 22 at the time and spoke little during casting calls and table reads, more inclined to observe what transpired. On set every day, he could often be found chain-smoking cigarettes between takes or spending time with his co-writer, Matt Elisofon, whom he had met in rehab, as well as two other friends.

Once, when Rob took exception with what the wardrobe department had chosen for the Thaniel character, he loudly voiced his disapproval. Then he stopped himself and called over Nick to ask his opinion.

“Nick was like, ‘Dad, I don’t know,’ and Rob says, ‘What do you mean you don’t know? Is this what you want onscreen?’” recalled Mr. Fernuik.

Both Rob and Nick could be intense, but those who knew them said it mostly seemed as if they were trying to work out the difficult feelings between them.

There were also some heavy moments of grief where Rob was forced to relive the past. In one scene, the movie’s main character relapses in a bathroom at Venice Beach. Rob became emotional while directing, tearing up.

Nick would later talk about the entire moviemaking experience as one that opened his eyes to his father’s talents.

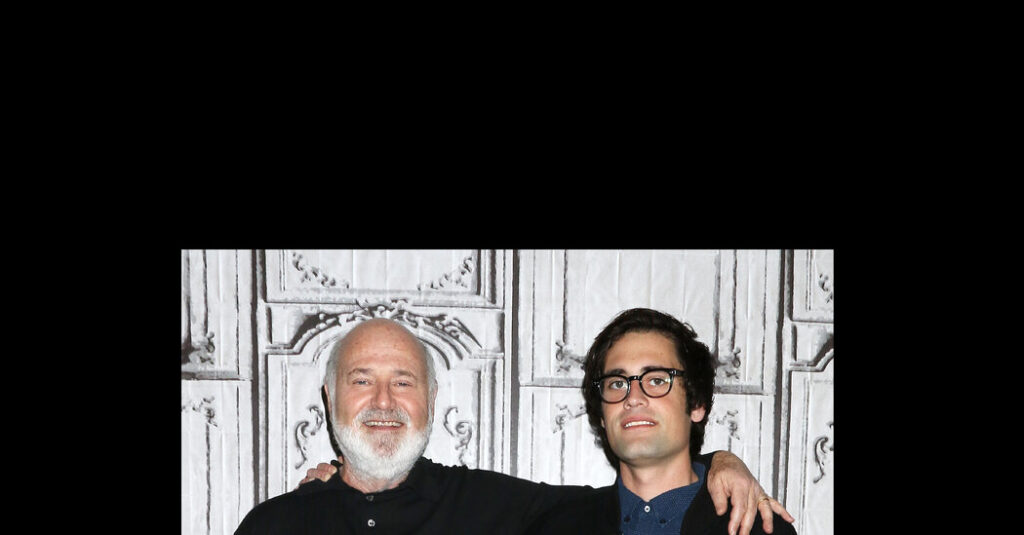

“I was like, Wow, he really knows a lot,” he said during an interview in 2016 at AOL’s headquarters in New York City. “It made me feel closer to him.”

Rob, in the same conversation, said the process had made him a better father, having been forced to understand more deeply just what Nick had gone through. “It was intense, it was difficult at times, but it was also the most satisfying, creative experience I’ve ever had.”

Both made references to a disconnect that had existed for a while.

Rob had bonded with his oldest son, Jake, over baseball, and the two were known to take trips around the country visiting stadiums, some of which had Rob throw out the first pitch. Jake had also, after a stint as a TV news reporter, taken the plunge into acting. Eerily, one of his latest bit parts was in “Monsters: the Lyle and Erik Menendez Story,” a Netflix series about two brothers who killed their parents.

Early on, Rob had also described his affection for his youngest child, Romy, how he couldn’t help but sing her medleys at bedtime. “I see myself a little bit different with Romy than I was with the boys,” he told The Los Angeles Times when his daughter was 9 months old. “I’m talking much more to her, interacting much more early on.”

Jake, now 34, and Romy, 27, both seemingly had a loving and playful relationship with their father, posting pictures with him on social media. “Happy Father’s Day to the man who I could talk to forever and also the man who I can sit in silence with and be perfectly content,” Romy wrote in a 2021 caption.

At 32 years old, Nick came across in some ways like the middle child who feels both lost in the shuffle and like the misfit. “We tried to mold him instead of celebrating his oddballness,” Rob told The New Yorker regretfully in 2016.

There was also the sense that Nick felt the weight of his father’s shadow, a pressure that Rob could comprehend as the child of the actor Carl Reiner. “I do understand him wanting to forge his own way,” Rob said in a 2016 interview with NPR. “I do know what that’s about, I went through it, and he’s brilliant and talented and he’s going to figure out his path.”

The Reiners’ candor during their press tour gave the impression that the dark days were behind them. During filming, Romy had posted a photo to Instagram with Nick. “love U,” it read. Jake later shared a photo of the siblings with the caption, “The trio.”

The entire family was spotted together in Los Angeles in September at the premiere of Spinal Tap II: The End Continues, a film Rob directed.

And then, an unraveling into the unthinkable.

On Sunday, the bodies of Michele, 68, and Rob, 78, were found inside their Brentwood home. They had been fatally stabbed. Nick was arrested on suspicion of murder and was being held without bail.

Friends and acquaintances now struggle to even speak about the family.

“They were my friends, and I’m dealing with it,” said Christopher DeMuri, a retired production designer who worked with Rob on three films, including “Being Charlie.”

At that time, he had witnessed a father and son attempting to communicate with each other to the best of their abilities.

“Their relationship was troubled, and they were trying to figure it out,” he said, “and in the movie, they did.”

Corina Knoll is a Times correspondent focusing on feature stories.

The post Rob and Nick Reiner: A Father-Son Relationship in Several Acts appeared first on New York Times.