Political memoirs tend to fall into recognizable categories.

There is the sanitized precampaign memoir, gauzy life stories mixed with vague policy projects and odes to American goodness. There is the postcampaign memoir, usually by the losers, assessing the strategy and sifting through the wreckage. There are memoirs by up and comers who dream of joining the arena and by aging politicos rewriting their careers once more before the obits start to land. There are memoirs by former staff members who realize that proximity to power gives them a good story and memoirs by journalists who chronicle power so closely that they imagine themselves its protagonists.

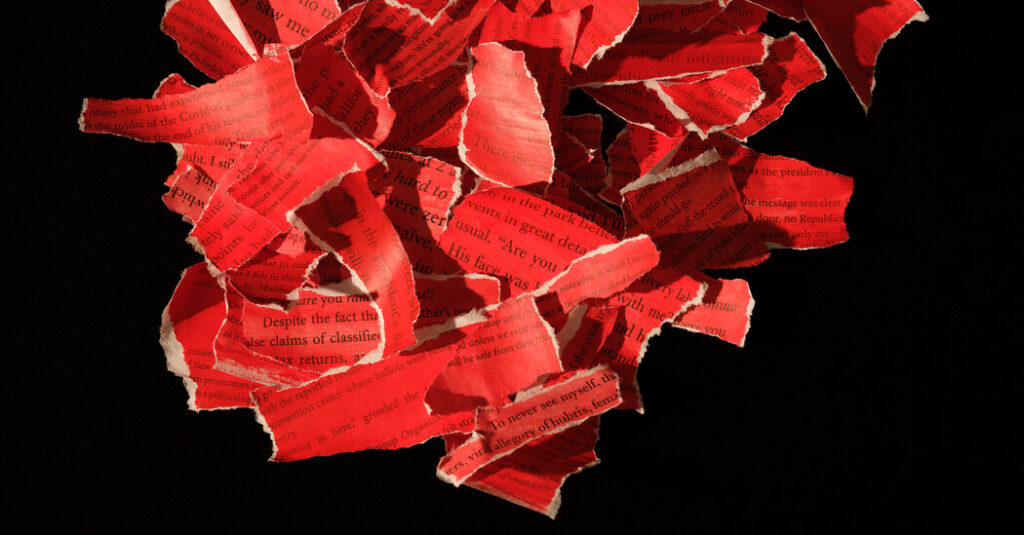

But a recent spate of books highlights the presence of a new category, one well suited to our time: the grievance memoir. In their books, Eric Trump (“Under Siege”), Karine Jean-Pierre (“Independent”) and Olivia Nuzzi (“American Canto”) are all outraged by affronts real and imagined, fixated on nefarious, often unspecified enemies, obsessed with “the narrative” over the facts and oblivious to their complicity in the conditions they decry.

The authors (a third child embracing on to his father’s legal and political grudges, a former White House press secretary groping for a new brand, a boutique political journalist enmeshed in a self-made scandal) are animated, above all, by a certainty that they’ve been wronged not just by people or institutions but also by broader forces. They are ancillary characters inflating themselves into victims, heroes, even symbols. It is the inevitable memoir style for a moment when everyone feels resentful, oppressed, overlooked — in a word, aggrieved.

Jean-Pierre, who served as President Joe Biden’s second press secretary, recounts her departure from the Democratic Party in favor of a newfound political independence. She is motivated not by differences on values or policy — she still supports “many of the party’s pillars” and remains “in sync with the vast majority of the Democratic base” — but by the shoddy treatment she feels he received after his disastrous debate with Donald Trump in 2024. Pushing Biden from the re-election campaign was “meanspirited” and “incredibly disappointing,” she writes, the betrayal of a statesman.

She blames party leaders and the political press, but the focus of her grievance is a more encompassing force: “the narrative.”

In her telling, Biden’s calamitous debate performance was troubling not because it laid bare serious problems with the commander in chief but because it “reinforced the growing narrative” about his frailty. “I braced for the narrative they’d spin after this shaky display,” she writes, criticizing the news media. “The debate gave credibility to the narrative they’d been building for a year.”

It is an occupational hazard of politics to assume that events and facts do not mean real things themselves but only strengthen or weaken prevailing narratives. (So postmodern!) In this world, reality is background noise that can be adjusted up or down or just ignored. Jean-Pierre dismisses Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson’s 2025 book, “Original Sin,” which detailed how campaign and White House officials camouflaged Biden’s decline, with uninformed ease: “I never read Tapper’s book and don’t ever plan to because that does not track with what I saw in the White House.”

Though she praises Biden’s patriotism and leadership, Jean-Pierre’s devotion to her old boss flows in part from what he did for her. She stresses that he “gave me an opportunity to make history as the first Black and openly queer White House press secretary.” She repeatedly cites her history-making credentials, based less on anything she accomplished on the job than on the fact that she held it at all. (She makes history on the first page of her introduction, then on Page 24, Page 31 and Page 41, and then I stopped keeping track.)

Unwittingly, she offers a damning verdict on her performance. The Democratic Party must ask “why it couldn’t articulate the achievements of the Biden/Harris administration well enough to get Harris across the finish line,” Jean-Pierre writes, as though articulating those achievements had not been the press secretary’s job. She acknowledges that the party’s messaging has been “ineffective” and “muddled” and says Democrats must move beyond the “poll-tested, talking-point-based way they have communicated or largely governed with for years.” OK, but wasn’t she standing at the lectern for many of those years?

As with her historic turn at the White House, Jean-Pierre has high hopes that her coming out as an independent “inspires more nuanced political conversations and a reimagining of the alliances and actions that can create a society truly supportive of all.” Such formulations proliferate in “Independent,” which calls for constructing paradigms, lowering political temperature, mending a fractured polity, becoming a force for change and other things that “we as a nation” can do — clichéd in phrasing, meaningless in practice.

Apparently, though, we as a nation are already urging Jean-Pierre to run for office. “I get asked this question two or three times a week,” she says, an experience that is “humbling, and, honestly, a little overwhelming.” (Politicians and journalists in Washington are never more humbled or overwhelmed than when bragging.)

These supporters all go unnamed, as do the numerous people who have approached Jean-Pierre in stores and pharmacies, with spot-on facial expressions, to tell her what a great job she’s doing. “Man, we could see you were holding it back today,” someone with a “knowing nod” tells her. “We saw you smile and take a breath,” adds a person with “a grin and a wink.” A Trump-supporting older white woman tells her, with perfect pitch, that “I don’t agree with everything you say, but you’re really damn good at it.” At one point Jean-Pierre almost fesses up to the shtick: “‘You do a good job,’ someone might say. ‘We don’t like your boss, but good for you for sticking up for yourself.’”

Someone might say? It is a set piece of the grievance memoir to have serviceable strangers, in perfectly quotable comments, validate the myths you’ve built around yourself.

In “Under Siege,” which recently spent three weeks on the New York Times best-seller list, Eric Trump is equally fixated on narratives. The F.B.I. search at Mar-a-Lago in August 2022 was an effort to “change the narrative” about the Biden administration’s failings. Journalists in Washington and New York invariably “create a false narrative for voters, all from the safety of their isolated studios.” The protests in the summer of 2020 seemed to be prompted by the killing of George Floyd — or were they “an excuse to change the narrative in an election year?”

Poor narrative. No one leaves it alone.

Trump’s counternarrative is that the Trump family has long lived under siege from government, media and law (though his preferred word is “lawfare”). He cites as evidence the two impeachments in the House of Representatives and the many indictments and investigations of his father and the Trump Organization, concerning business records, election interference and classified documents. Put together, he writes with typical Trumpian hyperbole, it is a siege “reminiscent of Stalin’s reign of terror in the former U.S.S.R.”

Trump has a point to make, especially about the New York case involving $130,000 in hush-money payments to Stormy Daniels — perhaps the weakest of the lot yet the only one to result in a conviction — but he undercuts it by avoiding the vital arguments and details behind them.

In 2020, President Trump wasn’t merely “questioning a sketchy, pandemic-weakened election” in Georgia, as Eric Trump asserts; he was demanding that state officials find 11,780 more votes for him, and it’s on tape. Eric Trump dismisses the case regarding his father’s “supposed” mishandling of classified documents, accusing the F.B.I. of “almost certainly” planting evidence at Mar-a-Lago. (Adding “supposed” to things you don’t like and “almost certainly” to things you do like doesn’t prove the point.) And though he never stops declaring that the 2020 election was fraudulent — “We were robbed,” he writes — he refers only glancingly to the “manufactured storm of Jan. 6,” dismissing the protesters as innocents who were just “taking pictures in the Capitol” that day. Fortunately, others took pictures, too.

Eric Trump almost seems to relish the siege, in part because, by his account, it thrust him into the arena. He brags about how many subpoenas he has received as a Trump Organization executive (“I am likely the most subpoenaed man in American history”) and emphasizes the leadership role he took in fighting back. “I would lead the company, lead my family, lead our defense against the lawfare,” he writes. He even says he became “a patriarch of sorts” in the Trump family. That is part of his own narrative — how much he resembles his father, who, according to Eric Trump, calls him the “sleeper” among his children, the one who is always “quietly exceeding expectations.”

.op-aside { display: none; border-top: 1px solid var(–color-stroke-tertiary,#C7C7C7); border-bottom: 1px solid var(–color-stroke-tertiary,#C7C7C7); font-family: nyt-franklin, helvetica, sans-serif; flex-direction: row; justify-content: space-between; padding-top: 1.25rem; padding-bottom: 1.25rem; position: relative; max-width: 600px; margin: 2rem 20px; }

.op-aside p { margin: 0; font-family: nyt-franklin, helvetica, sans-serif; font-size: 1rem; line-height: 1.3rem; margin-top: 0.4rem; margin-right: 2rem; font-weight: 600; flex-grow: 1; }

.SHA_opinionPrompt_0325_1_Prompt .op-aside { display: flex; }

@media (min-width: 640px) { .op-aside { margin: 2rem auto; } }

.op-buttonWrap { visibility: hidden; display: flex; right: 42px; position: absolute; background: var(–color-background-inverseSecondary, hsla(0,0%,21.18%,1)); border-radius: 3px; height: 25px; padding: 0 10px; align-items: center; justify-content: center; top: calc((100% – 25px) / 2); }

.op-copiedText { font-size: 0.75rem; line-height: 0.75rem; color: var(–color-content-inversePrimary, #fff); white-space: pre; margin-top: 1px; }

.op-button { display: flex; border: 1px solid var(–color-stroke-tertiary, #C7C7C7); height: 2rem; width: 2rem; background: transparent; border-radius: 50%; cursor: pointer; margin: auto; padding-inline: 6px; flex-direction: column; justify-content: center; flex-shrink: 0; }

.op-button:hover { background-color: var(–color-background-tertiary, #EBEBEB); }

.op-button path { fill: var(–color-content-primary,#121212); }

Know someone who would want to read this? Share the column.

Donald Trump loves to tell his followers to “fight,” and his son echoes the call. “This country needs fighters,” Eric Trump writes, and he hails his family’s supporters as “warriors.” But the enemy he fights in “Under Siege” is ill defined; sometimes it is a particular prosecutor or politician, sometimes it is “the left,” and sometimes just a hazy plural pronoun. “They smeared him, they impeached him twice, they weaponized law enforcement against him, they tried to bankrupt him, they removed his right of free speech, they took his name off ballots, and they charged him 91 times, threatening jail time for bogus crimes. Then they tried to kill him.”

This “they” makes for a remarkably elastic enemy — the same “they” who indicted Donald Trump can be the “they” who fired a rifle at him. The 2024 assassination attempt against him in Butler, Pa., “was just the next step in the escalation,” Eric Trump writes. “The attempt was exactly what they always wanted: his total and final removal.”

Much like Jean-Pierre, Eric Trump cites anonymous people who walk up to him and share their unsolicited outrage and support. “Hundreds of Americans” have told him how banks refused to finance their businesses because they support his father. A “seasoned investigator,” also unidentified, pulls him aside before a deposition to tell him that the case against him is nonsense and a “disgrace.” Even an incognito member of the Trump family texted Eric Trump this summer and apologized for publishing a book critical of his father. “I regret every day that I wrote that book,” the message read.

I doubt it was Mary Trump, the niece of Donald Trump who wrote the 2020 book “Too Much and Never Enough” and whom the president sued for providing financial documents to The New York Times. So maybe it’s Fred Trump III, the nephew who released “All in the Family: The Trumps and How We Got This Way.”

C’mon. Why make us guess — or wonder if it’s true at all?

For all the injustices that Eric Trump condemns in “Under Siege,” the book is indifferent to the attacks has father has launched against his own perceived enemies. “The weaponization of the United States’ justice system is real,” Eric Trump says. “These are words I never thought I would write.” He could keep writing them today.

But such an acknowledgment would take a modicum of self-awareness, which is in short supply in grievance memoirs. Eric Trump would rather spend his time “posting F-yous to all the haters and doubters,” as he puts it. Near the end of his book, he wonders if anger “only corrodes the soul,” if perhaps “grace is what’s needed now,” only to conclude that “I don’t have much of it in me.”

That much appears true.

When you complain about “disfigured public narratives about private matters,” as Nuzzi does early in “American Canto,” then perhaps your memoir could clarify those matters. But Nuzzi, who had an affair — emotional or digital or perhaps metaphysical or maybe just nonsensical — with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. while covering his 2024 presidential campaign and as a result lost her job as Washington correspondent at New York magazine, does nothing so enlightening.

Instead, she has written a book that, teetering between evocative and overwrought, crashes right through overwrought, splats into ridiculous and rolls in the muck of unintelligible — all while attempting to be literary. “Lines recede, borders dissolve, when you look very closely for very long at anything,” Nuzzi writes. “The familiar fades into the foreign. You do not know and then you know so well and then you walk through the door of your life for the first time again.”

Over the years, I’ve appreciated Nuzzi’s political profiles in New York magazine — as well as her posts about the foibles of political journalism — but I do not know what much of “American Canto” means or what the intended audience may be. Is it Kennedy, whom she refers to only as “the Politician” and with whom she still appears somewhat smitten? Is it her ex-fiancé and vengeful Substacker, Ryan Lizza, whom she alludes to only as “the man I did not marry”? (She makes a point of stressing that she was the one who left, that the engagement ring felt like a burden, that Lizza’s infidelity did not trouble her, that she pitied him and that she’s heard he would still take her back, so, yes, clearly everyone has moved on here.)

But no, “American Canto” seems even more navel-gazing, as though Nuzzi’s audience of one is herself. The book reads like diary entries packed between hard covers binding self-indulgent, meandering pages. (I know the book reads like her diary because a little past halfway, she drops in a few pages’ worth of old journal entries, and italics aside, it’s hard to tell the difference.) She attempts some Didionesque flourishes — she carries around Joan Didion’s 1987 book, “Miami”; constantly mentions the Santa Ana winds; and calls California “the cliff at the end of the country,” like Didion, who said it was “where we run out of continent”— but the result is more like The Trite Album.

Nuzzi acknowledges a “monumental” error that “collided my private life with the public interest,” yet she rarely takes responsibility for it. She was used to getting away with things, she explains, because she’d been “named to all the silly lists that connote mainstream status and valorize youthful achievement” and was therefore considered “good for business” by her employers. At one point she describes journalism as “the one place where I could never lie” and then admits that she breached “the threshold of this pristine territory,” but she appears more eager to describe her persecution than own her mistakes.

Nuzzi laments that “birds of prey” are circling around her, that she was the victim of a “siege” — that word again — of “hyper-domestic terror,” that the Politician had “orchestrated a narrative in which I was not just reduced to my sexuality but into a hypersexualized honey pot” and that “the man I did not marry” might kill her. (In the book she says that her brother once asked her if he could kill Lizza and that she said no, so maybe they’re even.)

However unforgivably the men in her life behave — and they do seem to — there is one man who becomes even more crucial than Kennedy or Lizza to her tale. It is Donald Trump. Attempting to place her story in the sweep of history, she ties her transgressions to him. “The lines I crossed,” she writes. “I am talking, of course, about how it happened between me and the Politician. I am talking, of course, about how it happened between the country and the president. I cannot talk about one without the other.”

This is the self-absolution of the grievance memoir: Things did not just happen to me; they happened to us.

Throughout her book, Nuzzi revisits her coverage of the president, offering insights that by now seem, like their subject, old and tired. Crowd sizes are his favorite metric, she reports. Despite his “Apprentice” fame, he has a hard time firing people. Loyalty, for Trump, is “a vow that went in one direction.” And the president became a “mirror” in which the country sees itself reflected. “American Canto,” she writes in her author’s note, is about “character” — her own and Trump’s and “that of the country he has so affected.”

It is not clear to me why Nuzzi’s story is inextricable from Trump’s, unless she is suggesting that his habit of picking and choosing the reality he believes and the principles he upholds somehow transformed her, along with so many more. “His lawlessness inspired lawlessness,” she writes. “His rejection of norms called norms into question.” She says she was “trapped in the field of his distortion” and that she could feel “the unstoppable start of the pulling apart and apart and apart and apart.”

Is this what led her to commit journalistic malpractice? Is it what made Nuzzi, by her own admission, lie to her bosses and to reporters about her relationship with Kennedy and to advise him on political strategy while still imagining herself a journalist? Should we just blame it all on the distortion field generated by Trump?

It’s a convenient explanation; you might even call it a narrative. That thing we call Trump world, Nuzzi explains, is not just the people surrounding the president, jostling for influence or begging for scraps. “It began to feel like a description of the country unzipped,” she writes, “the state of disunion and delirium in the distortion feel that engulfed the whole of us amid his rise.”

That “unzipped” cannot be accidental, can it?

Ben Bradlee, the longtime Washington Post editor, had a line he laid on reporters who were too enthralled with a story that he considered unimportant. “When the history of the world is written,” he’d say, “this will not be in it.”

Much the same could be said for the tribulations of Karine Jean-Pierre, Eric Trump and Olivia Nuzzi. In the history of this time, they will be footnotes to footnotes — notable, to me at least, only for the odd literary canon they have produced.

The signature move of the grievance memoir is to combine deep indignation with a loosely identified scapegoat — the Trump era or the narrative or the left or the all-purpose “they.” Tackling such imposing enemies with such self-righteous writing makes marginal figures appear more consequential in their own words or their own minds.

Though their motives appear narrow and their worlds small, the grievance memoirs latch onto the highest and most predictable of moral terrain. Jean-Pierre says she is speaking out so that “we as a nation pull back from the brink, regain our footing and move toward empathy.” Eric Trump says it would be easy for his family to end the siege against them by leaving political life behind, but they’re just too stubborn. “The truth is,” he writes, “we truly love this country.” And Nuzzi says her book is “about love, because everything is about love, and about love of country.”

They did it all for love of America. In this one way, the grievance memoir is not so novel. It fits right in.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post Olivia Nuzzi, Karine Jean-Pierre and Eric Trump Have All Written the Same Book appeared first on New York Times.