Can a French horn be played with a fish in its bell? Or a trombone if filled with water? An experimental composer might tackle these questions in a piece about threats to ocean wildlife or rising sea levels, but, nearly two centuries ago, one young musician asked them for a less noble purpose: revenge.

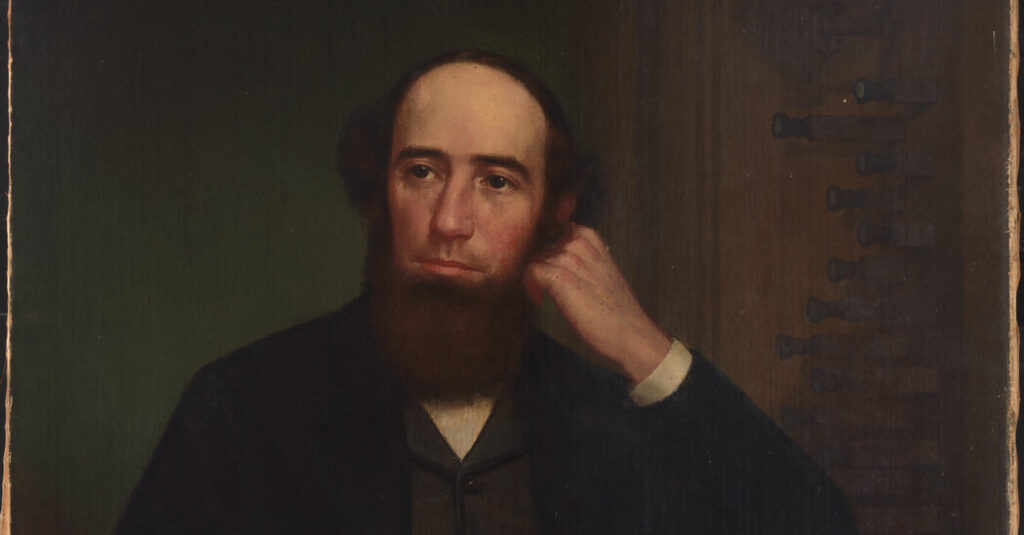

That man was George Frederick Bristow, born 200 years ago this month. He was one of the country’s finest early composers, a musical jack-of-all-trades, a compassionate schoolteacher, a skilled fisherman and, yes, a prankster.

Bristow venerated the European classical tradition and wrote squarely within it. But, capturing a growing sense of cultural independence, he used tried-and-true genres like the symphony to tell American stories with musical sounds and imagery familiar to ordinary people.

As the United States looks toward its 250th anniversary next year, reflecting on Bristow’s accomplishments in a harsh environment for American musicians can help us appreciate the resilience required to make classical music a living, vital art in this country.

Born in Brooklyn and aptly named after George Frideric Handel, Bristow began piano lessons with his father at age 5. He recounted that sweat poured down his father’s face while teaching him to read music, an anxiety that faded only when George received an encore at his debut recital four years later.

George’s father performed in local theaters, and the boy followed his lead. Theater orchestras at the time could be anything from a motley crew missing several instruments or a full complement of skilled professionals. By age 12, George had progressed from making 75 cents a night on percussion to $8 a week on violin. Much to his annoyance, his taskmaster father pocketed the cash.

Bristow’s trajectory rose with the founding of the Philharmonic-Society (now called the New York Philharmonic) in 1842. He and his father were inaugural members, but, during its first season, older musicians forced George to substitute in theaters on nights when they were double booked. He naturally wanted to play great classical repertoire with them and rebelled.

Seeking payback, he caused all kinds of trouble, like ruining the brass instruments, greasing a cello bow and dousing the community snuff box with lamp oil. One of his first victims was his father. And the strategy worked: George performed as a Philharmonic violinist every season for all but one of the next 40 years.

Bristow’s colleagues highly valued his instrumental talents. Beginning in 1850, he served as concertmaster of both the Philharmonic and the famed Swedish soprano Jenny Lind’s touring orchestra. He also performed as a soloist with the Philharmonic on two occasions, on violin and piano.

But his most ambitious goal was composition.

The Philharmonic’s founding documents required it to program at least one “Grand Orchestral Composition” written in the United States each season. It first followed through in 1846, with an overture by George Loder, an English theater orchestra director from Bristow’s youth. A year later, Bristow became the first American-born composer to benefit from the policy when the orchestra premiered an overture one critic panned as unoriginal. Unfazed, he convinced Jenny Lind’s conductor to open concerts with it.

Eventually, the Philharmonic lost its resolve to program new American music, leading to complaints that it had abandoned a core aim. A prominent magazine reported in late 1849 that the public was growing impatient after learning the Philharmonic had slow-walked the premiere of Bristow’s First Symphony. Hostility grew into May 1850, forcing the orchestra to schedule the work hastily at season’s end.

Bristow’s champions, especially the composer-critic William Henry Fry, saw the move as a token gesture rather than reform. In February 1853, he chastised the Philharmonic for not doing more to support Bristow, or any American. The New-Yorker Staatszeitung, a German American newspaper, argued that Bristow’s symphony should be performed in “London, Paris, Hamburg, Berlin, Leipzig and Vienna” — rare praise from that immigrant community.

Soon, Bristow would get his revenge against the prickly Philharmonic again. The magnetic, foppish London-based conductor Louis Antoine Jullien arrived in the United States later that year with an all-star orchestra and immediately began performing American pieces, including music by Bristow, on an extended tour. Audiences everywhere loved it all.

Fry used his column in The New-York Daily Tribune to embarrass the Philharmonic after the successful premiere of an excerpt from Bristow’s Second Symphony, which Jullien had commissioned.

“Is not New York as large as Vienna and larger?” Fry wrote, referring to the Vienna Philharmonic, which had also been founded in 1842. “Then why defer to any German town?”

Jullien’s advocacy of American works led the controversy to boil over in 1854, mostly at Fry’s instigation. The ordinarily reserved Bristow entered the fray when the Philharmonic’s defenders noted that the orchestra would perform more American music if it were good enough. Naturally, he was insulted.

“Is there a Philharmonic Society in Germany for the encouragement solely of American music?” he fumed. “If all their artistic affections are unalterably German, let them pack back to Germany and enjoy the police and bayonets and aristocratic kicks and cuffs of that land, where an artist is a serf to a nobleman.”

Incensed, Bristow immediately resigned as concertmaster of the Philharmonic and refused to perform for the entire next season.

Jullien continued to prove that Bristow’s music was good — precisely the payback he needed. After returning to Britain that summer, Jullien programmed it there. The concertmaster of his orchestra told Bristow that British audiences considered him “the American composer.”

Bristow used his Philharmonic hiatus to pursue other projects, notably his opera “Rip van Winkle,” as well as numerous engagements as a conductor, pianist and organist, his biographer Katherine Preston has chronicled. He served just deserts when the Philharmonic agreed to perform the full Second Symphony upon his return as a violinist during the 1855-56 season. We may never know if that was a negotiated settlement.

If Bristow’s name is known today, it is likely for his stand against the Philharmonic. But his career continued to flourish and evolve over the next several decades.

Most notably, “Rip van Winkle” signified a shift in his compositional focus toward American subjects, delighting his patriotic supporters. Patrick S. Gilmore, a celebrity bandmaster, programmed the “Great Republic Overture” in Philadelphia as a centerpiece on Independence Day in 1876. And the “Jibbenainosay Overture,” inspired by the American novel “Nick of the Woods,” graced the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

The Brooklyn Philharmonic commissioned Bristow’s most pictorial work in this vein, the “Arcadian” Symphony, and premiered it in 1873, scooping his old Manhattan enemy. This music paints an evocative portrait of westward settlers, with the four movements depicting their stark journey, evening rest, a stereotyped Native American “war dance” and their joyous arrival.

Other major pieces, including a Mass and two oratorios, augmented Bristow’s profile as a choral director in sacred and secular contexts. One critic described the oratorio “Daniel,” premiered by the Mendelssohn Union in 1867, as “the most important musical work yet by an American.”

Like his European contemporaries, Bristow also wrote prolifically in small genres: songs, piano miniatures and chamber music, all revealing characteristic charm. Today, the gossamer strands of “Dream Land” for piano could easily serve as a compelling recital replacement for canonical 19th-century preludes, nocturnes or intermezzos.

Bristow’s catalog includes easier works aligning with his decades-long career as a music teacher in Manhattan’s public schools, which began around the time of his Philharmonic resignation. Contrary to his outward stubbornness during the feud, his work with students shows a softer side. Many of his pupils were first-generation German immigrants, perhaps even the children of his orchestra colleagues.

In 1870, Bristow requested permission from a school board overseeing his German-speaking students to enlist hundreds of them, ranging in age from 7 to 14, to participate in a Grand Juvenile Festival celebrating Beethoven’s centennial. At a performance “crowded to the last inch,” children dressed in white sang excerpts by Mendelssohn, Bellini, Rossini and, of course, Beethoven. One enthusiastic critic remarked that Bristow was “accomplishing wonders.”

Try as he might to steer clear, controversy continued to find Bristow, the quiet fisherman, in his twilight years at his home in the Morrisania area of the Bronx.

In May 1893, the Czech composer Antonin Dvorak, having recently arrived in New York, proclaimed that American composers should adapt African American folk song into classical idioms to develop a distinctively national style. Debates about music, race and national identity raged in the press until the Philharmonic premiered Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony in December, only to reignite.

For his part, Bristow said little, but one observer remarked that the elder statesman’s latest symphony included a “breakdown” — an African American dance — making Bristow “the first” composer to incorporate Dvorak’s ideas in an actual piece. (That wasn’t exactly true.)

This new symphony, subtitled “Niagara,” was a gigantic choral work echoing Beethoven’s monumental Ninth. Stylistically eclectic, it includes intentional quotations of Handel, Protestant hymn tunes, parlor songs and folk dance, all wrapped in Bristow’s characteristically learned forms and Mendelssohnian orchestral coloring.

Capturing the majestic wonders of Niagara Falls, a potent natural symbol of boundless possibility, the symphony’s 1898 Carnegie Hall premiere planted Bristow’s final American musical flag. He died suddenly after collapsing at school a few months later.

Next month — and with brass instruments free of unwanted liquid obstructions — the American Symphony Orchestra and Leon Botstein will give “Niagara” its second performance ever, again at Carnegie Hall.

If it’s a roaring success, that could be Bristow’s greatest act of revenge yet.

The post It Wasn’t Easy Being a Founding Father of the American Symphony appeared first on New York Times.