Eli Schlanger was the kind of rabbi who would come to my house to tell me crazy stories full of chance and coincidence. They usually ended with him in a remote Australian prison, reciting psalms with an unexpectedly Jewish inmate or arranging a circumcision to fulfill the final wish of a dying man. He saw the divine hand in everything; he lived to bring the light.

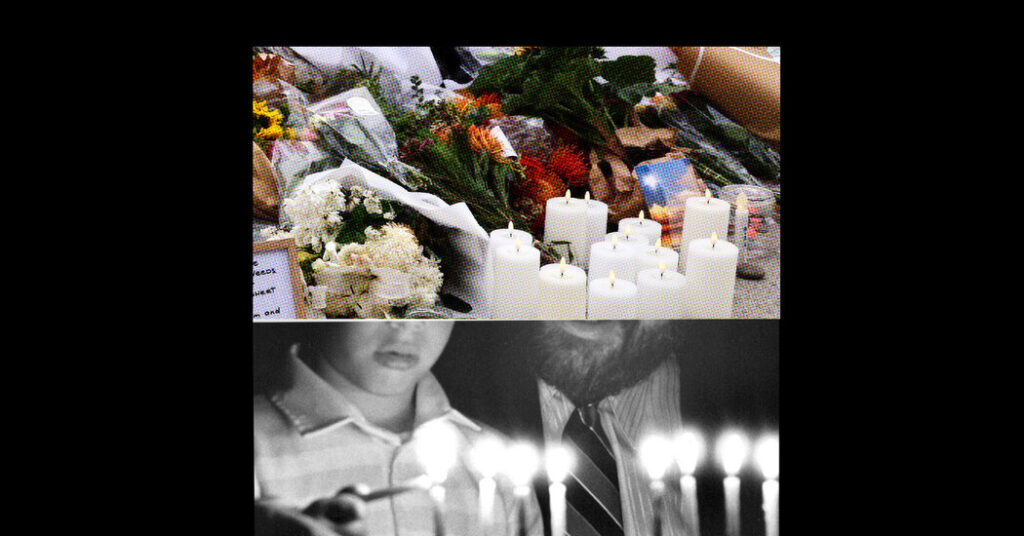

On Sunday night, a man who had never let anyone down and never stopped working for his community was let down by us all. The suspects in my rabbi’s slaughter are a father and son who came armed with hunting rifles to a Jewish event on the grass overlooking Bondi Beach in Sydney, an event with jumping castles and jam-filled doughnuts. Fifteen people were killed and dozens were wounded.

They were all let down by a government whose role it is to do the things individuals cannot do for themselves: chiefly, keep our nation safe from terrorism and mass shootings.

They were let down by a society that has stood by and watched the crisis of antisemitism play out with a startling predictability. Rates of serious vandalism, harassment and physical abuse targeting Australia’s Jews saw a fivefold increase in the two years since the attacks on Israel by Hamas on Oct. 7, 2023, according to my organization’s latest report. Arson targeting synagogues and Jewish businesses has been carried out to devastating effect. It was later revealed that Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps had orchestrated several of the attacks using local networks of petty criminals for hire and organized crime middlemen. The men accused of carrying out the attacks this week were motivated by the Islamic State, the government has said.

Now our nightmare has come to pass.

Most of the 15 people who were killed on Sunday belonged to a congregation made up mostly of Jewish migrants from the Soviet Union. We were once something of a communal oddity, having arrived in Australia speaking little Hebrew or English, knowing few customs or Jewish laws and limited by language and poverty in how we could contribute to the life of the Jewish community. This caused us to band together, elevate one another and form a community within a community, a family of families.

We now form an integral part of wider Australia. Jews were among the first Europeans to come to this country. As many as 14 Jews sailed from England on the First Fleet of convict ships in 1788. The nation’s greatest general, Sir John Monash, was Jewish, and we have contributed to the science and culture of this country out of all proportion to our small numbers.

We have done so much for Australia because we adore it. We know that not all nations are like this one. We who witnessed the horrors of Nazism, of Stalinism, of South African apartheid knew our incredible good fortune to be part of a country that has long prided itself on its diversity and inclusion.

The last two years have demonstrated how fragile our position within Australia truly is. When a mob assembled at the Sydney Opera House on Oct. 9, 2023, to revel in the Jewish community’s sorrow two days after the Hamas attacks in Israel and chanted that “the army of Mohammad will return,” among other threats, the Jewish community — and other Australians, too — called upon the prime minister to lead this country away from the abyss of hate.

Instead the government dithered, uttering bland condemnations and calls for general calm that signified nothing. It did create a special envoy for combating antisemitism in July 2024, and Jewish leaders urged the government and civil society to get behind an antisemitism strategy that the special envoy presented before someone got killed. The strategy was never formally endorsed by the government, let alone implemented.

History shows us that antisemitism left unchallenged does not dissipate or present as mild bigotry. It has a unique consumptive power that drives individuals into paranoia and inhumanity. Perhaps the government did not fully appraise the character of this hatred, or perhaps it considered that policies and firm rhetoric seen to favor the Jewish community would be electorally unpopular. When violent chants shifted to physical assaults, serious vandalism, the abuse of schoolchildren and firebombings of Jewish targets, we warned that we were seeing a process of dehumanization that could only end one way.

Now we have suffered a loss that is impossible to measure or articulate. It is a loss felt nationally for a country that is forever changed. It is a loss felt communally for a way of life defined by pride and open observance that no longer exists. And it is a loss we feel individually for the friends and relatives who died in our arms from hideous wounds inflicted by high-powered shells used for hunting game.

The loss of my rabbi has crushed me. Seeking out every opportunity to help anyone who needed it, he measured his days in good deeds performed. He amassed no personal wealth, but was overflowing with the true love of all who knew him.

My community will never recover from this, I am sure. My rabbi, my friend, Eli Schlanger lived by a mission of being proud of who he was as a Jew. The annual Hanukkah event he hosted on the beach was the ultimate evidence of our acceptance, the proof that we were safe in our acts of community pride.

That is all gone now. And with it, a man who had shown us the way.

Alex Ryvchin is the co-chief executive of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry and the author of “The Seven Deadly Myths,” a recent history of antisemitism.

Source photographs by David Gray and Denver Post, via Getty Images.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post Australia Can’t Recover From This appeared first on New York Times.