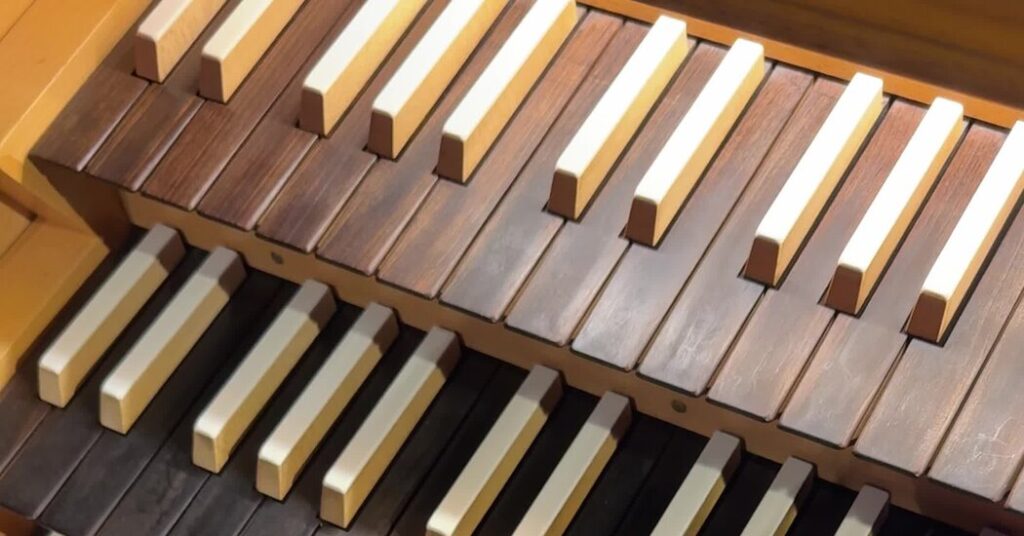

On a dark December afternoon, Ellen Arkbro was sitting at the organ in the hulking Gedächtniskirche church in Berlin, conducting an acoustic experiment. While her right hand held down a chord on one of the instrument’s four keyboards, she prodded buttons on the console with her left. There were hints of silvery flutes, throbbing strings and pungent reeds as she cycled through combinations of pipes. The chord seemed to shimmer and glisten in the air.

Finally, Arkbro found the configuration that matched the sound in her head: something both plangent and bluesy, yet with an otherworldly purity.

She paused as the music flooded the building, listening intently, then lifted her fingers off the keys. “I’m not even an organist, not really,” she said with a grin. “I’m kind of making it up.”

That may be true, or not, but Arkbro is almost certainly one of the most interesting composers for the instrument working today. “Nightclouds,” the piece she was running through in advance of a retrospective of her work in New York that begins Wednesday, eludes straightforward description. The title track of an album released this year, it consists of dreamy, gauzy tone clusters that shift and churn with no defined melody or pulse.

At times, the album sounds indebted to the French composer and organist Olivier Messiaen; at others, to the American minimalist Morton Feldman. Reviewers have also reached for comparisons to the jazz guitarist Allan Holdsworth and noted echoes of blues and Indian ragas. The tracks feel like thoughtful essays in musical color, but also invitations to switch off and bliss out.

Maybe trying to pin down Arkbro’s approach too precisely misses the point. Like the clouds that the 35-minute album is named for, it never seems to take a stable shape.

“Ellen’s music really holds space,” the music writer and broadcaster Jennifer Lucy Allan said in a phone interview. “You have to sit down. It forces you to listen.”

Though she now lives in Berlin, Arkbro began her sonic adventures in Stockholm, where she was born in 1990. Her father’s collection of punk and post-punk records was one early influence — “I was a very heavy My Bloody Valentine fan,” she said — and after taking piano and guitar lessons, she experimented with jazz and formed a teenage skate punk band with friends.

After joining one of Stockholm’s choir schools, Arkboro became obsessed with microtonal intervals — the infinite rainbow of pitches produced by string instruments or the human voice as opposed to the rigid 12-note tuning of instruments like the piano. She went on to study at Stockholm’s famed E.M.S. electronic music studio, soaking up sine and sawtooth waves as well as lectures on advanced acoustics, then came into the orbit of the experimental Swedish composer Catherine Christer Hennix.

In 2014, with Hennix’s encouragement, she traveled to New York to learn from La Monte Young, often called the father of minimalism, whose works can last for hours.

“That was where I realized how slow music could be,” Arkboro said. “I remember hearing La Monte’s music for the first time, and thinking, ‘Is this allowed, for the music to go on so long? It was amazing.”

Arkbro’s breakthrough piece, which became her first album when it was released in 2017, was certainly slow moving. Titled “For Organ and Brass” and inspired by her encounters in Stockholm with a meantone organ — an instrument tuned in pure tones, a musical system common during the Renaissance and early Baroque periods — it features trance-like block chords that can sound seductive, mournful, joyous or downright sinister. The music is both bracingly medieval, an effect of the organ’s spicy tuning, and curiously futuristic.

The album that followed two years later, “Chords,” is more severe, blending organ and guitar drones with synthesized sounds to create dizzying constellations of frequencies.

“I like exploring the space of sound and the way it interacts with how you listen,” Arkbro said. “It’s almost like an installation; if you tilt your head, you hear different things.”

Arkbro has a taste for using traditional, and often antique, instruments in arresting new combinations: One 2022 composition is for three tubas; another, premiered at last month’s Music Biennale in Venice, for three bass violas da gamba. She said she was currently working on a composition for a reed organ plus four crumhorns — medieval double-reed instruments noted for their blaring, honking quality and habit of straying wildly out of tune.

“Even if it’s somewhat failing, I like the idea of reaching for something a little beyond,” she said.

But before she has time to resolve the complexities of making crumhorns do what they’re told to, there is the New York residency, curated by the arts nonprofit Blank Forms, which will offer an impressively broad swath of her output.

“They told me they wanted to call it a retrospective, but I said, ‘I’m only 35!’” Arkbro said. “So we settled on ‘sonic portrait’.”

Solo works such as “Nightclouds” and a piece titled “Blues for Bassoon” are on the program alongside a recent collaboration with the spoken word artist Hanne Lippard and the organist Hampus Lindwall, recently released as an album called “How Do I Know If My Cat Likes Me.”

Lawrence Kumpf, Blank Forms’ director, said that he hoped the event would showcase the formal rigor of Arkbro’s music, yet also its generosity of spirit. “Ellen’s music exhibits an extreme dedication to structure — it’s stripped back and precise, but also incredibly emotive,” he said.

Arkbro said that, after two album releases during the summer and a hectic fall of live performances and premieres, the New York dates would be an opportunity for her, too, to listen and take stock.

“Maybe it sounds strange, but I sometimes wonder what my life is, what have I made?” she said. “Then, every so often, I get little glimpses.”

Nightsongs, Daysongs

Wednesday at Dia Chelsea and Thursday at Greene Naftali in Manhattan; www.blankforms.org.

The post A Pipe Organist Invites You to Bliss Out to Her Dreamy Colors appeared first on New York Times.