While writing the novel Hamnet, which imagines the hidden origins of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the author Maggie O’Farrell did something counterintuitive: She avoided referencing or quoting the Bard as much as possible. Characters never utter his name. The narrator mentions him obliquely, as the husband of Agnes Hathaway and the father to two daughters and a son, the titular Hamnet. As a child, Hamnet dies during the plague—a loss that O’Farrell depicts as catalyzing Shakespeare’s tragic play about the Danish prince. (The theory that Hamnet’s death led to Hamlet comes from the names Hamnet and Hamlet being interchangeable around the turn of the 17th century, when Hamlet was written.) Only a single line from Hamlet gets spoken, and not until the book’s end. “You can’t cut and paste large speeches of Shakespeare and put them into a novel,” O’Farrell told me last month. “It just doesn’t work on the page.”

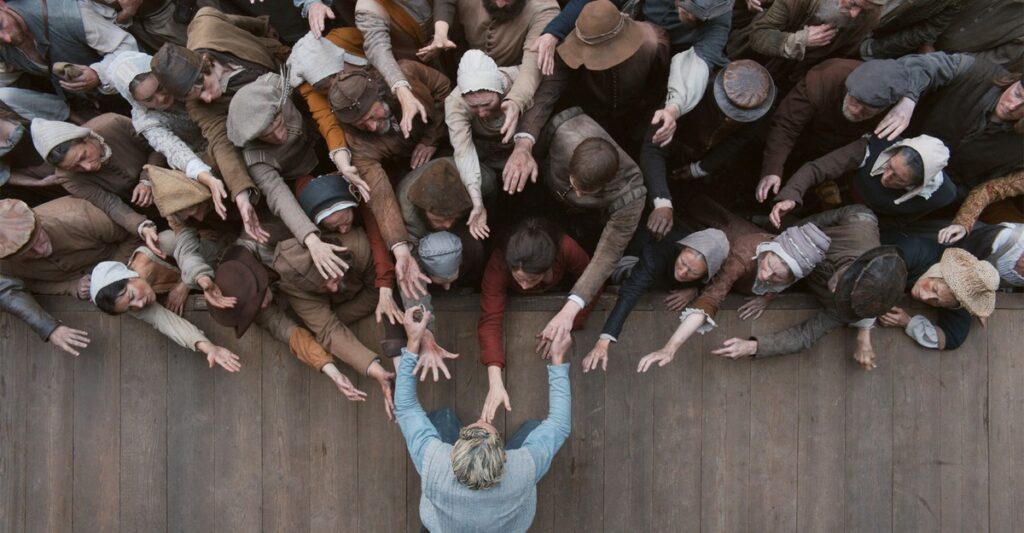

Telling the story on-screen, however, was different. The film adaptation of Hamnet, co-written by O’Farrell with the movie’s director, Chloé Zhao, embraces the playwright’s work wholeheartedly. It expands Shakespeare as a character, transcribes portions of Hamlet, and reproduces the totemic “To be, or not to be” soliloquy not once, but twice. In the first instance, William (played by Paul Mescal), better known as Will, delivers it while contemplating what to do after Hamnet’s death. In the second, Agnes (Jessie Buckley) watches an actor recite the speech during a production of Hamlet, grasping in his performance something she previously could not about her and her husband’s grief. Both moments reinterpret the soliloquy as an extended conversation between two characters—two parents, one of whom is the writer himself—as they navigate the unfamiliar country of life after death.

[Read: The long history of the Hamnet myth]

As effective as the scenes are in the finished film, Zhao was torn about including the soliloquy. The director, who won an Oscar for the pensive Nomadland, wanted Hamnet’s screenplay to incorporate more Hamlet, but, she told me, “there’s a very fine line you have to walk.” The story focuses on Agnes and Will’s marriage and how their divergent approaches to mourning test their bond—Agnes’s sadness curdles into rage, whereas Will turns inward, pouring his feelings into his work. Including such a familiar speech risked, as Zhao put it, being “too much,” a distraction rather than a way to convey the characters’ anguish.

Mescal convinced her that the addition was necessary as he worked on processing his character. The actor felt that Will was not just trapped by his pain but also being pulled in opposite directions—a sentiment Zhao recognized that Shakespeare had captured best. The words “To be, or not to be” wrestled with, as she put it, “the great paradox of the universe” exemplified by Hamnet’s death. “It’s so unimaginable that we were born to die, right?” she said. “It’s like a big cosmic joke.”

Hamlet may be a dream role for many actors, but it also invites heavy scrutiny. The play is perhaps the most adapted of the Bard’s works, with numerous silent features, 20 major sound versions, and a litany of spin-offs and movies that are loosely based on it, such as Ophelia. Lines from the play—“Something is rotten in the state of Denmark”—are as recognizable as the image of a man holding a skull, no matter where the events take place: in contemporary New York City, corporate Japan, the African Savannah.

The “To be, or not to be” soliloquy sets a particularly tricky trap. On-screen, the speech’s prestige can overwhelm its existential subject matter, and the passage tends to get overacted. “Because it’s a beautiful speech,” Peter Kirwan, a professor of Shakespeare and performance at Mary Baldwin University, told me, “the beauty of the speech kind of takes away from what it actually means for someone to be working through this.” The fact that any soliloquy halts dramatic action also poses a challenge. Onstage, an actor can naturally hold an audience’s attention, being in the same physical venue. Cinema’s visual language, though, has the potential to undermine the words’ meaning. The sentiment can become a spectacle more than an interior reflection made exterior.

Across film history, “To be, or not to be” has often been interpreted in one of two ways. Some movies, such as Laurence Olivier’s 1948 Hamlet, underline the speech’s raw power as a peek inside a conflicted hero’s mind. The soliloquy is heard partly as a voice-over while Olivier’s Hamlet positions himself on a cliff, emphasizing his mental turbulence. As a result, Lucy Munro, a professor of Shakespeare at King’s College London, explained to me, “you want to see what he does next, but you also want to see what he thinks next.” Other movies approach the passage as an opportunity to further convey the stakes. In the 1996 adaptation, which tangles with contemporary ideas such as surveillance, Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet delivers the speech before a two-way mirror; the moment, Kirwan said, “becomes both an overt reflection of his interiority but also seems to be expressing a challenge to the people behind the mirror.” On rare occasions, the lines are taken out of their original context entirely. In Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider, an Indian adaptation of Hamlet set in Kashmir, Hamlet is reimagined as a political activist, and “To be, or not to be” is rendered as a political slogan.

[Read: In Shakespeare’s life story, not all is true]

Hamnet’s approach transforms the soliloquy further. The words are both divorced from Hamlet and indebted to it by the end of the film. They’re spoken by the play’s creator, then by the actor starring as Hamlet in its debut at the Globe Theatre. The first scene recalls adaptations such as Olivier’s: Will is next to the roiling River Thames, perched precariously on a wall as he struggles to process his grief. The second scene is akin to a take like Branagh’s, highlighting the observers—in this case, Agnes and the audience around her—taking in the soliloquy. Hamnet’s iterations of “To be, or not to be” form two halves of a complete narrative arc: Will’s recitation is a private expression of chaos; Agnes’s viewing is a public tableau of order. The speech offers each of them a semblance of peace, and the play reconnects them: By placing their strife on display, Will finally reaches Agnes through the performance.

In a way, Hamnet’s treatment of the soliloquy also updates the passage. Each generation’s takes on Hamlet tend to be imbued with the values of their time, Kirwan pointed out. Shakespeare’s play echoed the interrogative, anxious mood of the late-Elizabethan era; Branagh’s film confronted modern political overreach; Hamnet perhaps fits into our current social-media age by underlining the inclination to share even the most intimate thoughts. The film involves Shakespeare himself broadcasting his inner turmoil. “The interior,” Kirwan said, “is becoming public again.”

The question of what drove Shakespeare to write Hamlet is an irresistible riddle, and theories abound: Maybe his son’s death did lead Shakespeare to write Hamlet. Or maybe the Scandinavian folk figure Amleth actually planted the seed. Shakespeare’s words draw power from their malleability. But Hamnet goes beyond imagining what went on in Shakespeare’s head. The story, Zhao told me, offers a way to better understand the act of producing art. To her, Hamnet shows how creativity exists as a primal force, able to “alchemize one’s grief.” “We try to create a mystery around geniuses and artists, as if they somehow have a more special mind or something,” she said. But in Hamnet, the “To be, or not to be” meditation is infused entirely with the tumult of loss and moving on—feelings anyone can grasp. “The soliloquy didn’t come from the intellectual mind,” she explained. “It came from the tension in the body.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

The post What Does It Take to Reinvent Shakespeare’s Most Famous Soliloquy? appeared first on The Atlantic.