For the last year and a half, two hacked white Tesla Model 3 sedans each loaded with five extra cameras and one palm-sized supercomputer have quietly cruised around San Francisco. In a city and era swarming with questions about the capabilities and limits of artificial intelligence, the startup behind the modified Teslas is trying to answer what amounts to a simple question: How quickly can a company build autonomous vehicle software today?

The startup, which is making its activities public for the first time today, is called HyprLabs. Its 17-person team (just eight of them full-time) is divided between Paris and San Francisco, and the company is helmed by an autonomous vehicle company veteran, Zoox cofounder Tim Kentley-Klay, who suddenly exited the now Amazon-owned firm in 2018. Hypr has taken in relatively little funding, $5.5 million since 2022, but its ambitions are wide-ranging. Eventually, it plans to build and operate its own robots. “Think of the love child of R2-D2 and Sonic the Hedgehog,” Kentley-Klay says. “It’s going to define a new category that doesn’t currently exist.”

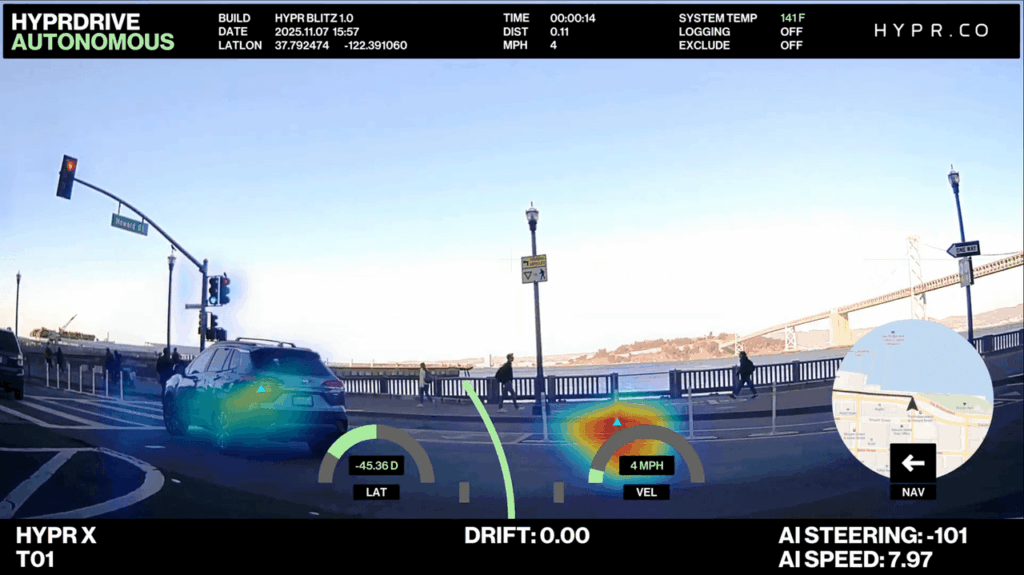

For now, though, the startup is announcing its software product called Hyprdrive, which it bills as a leap forward in how engineers train vehicles to pilot themselves. These sorts of leaps are all over the robotics space, thanks to advances in machine learning that promise to bring down the cost of training autonomous vehicle software, and the amount of human labor involved. This training evolution has brought new movement to a space that for years suffered through a “trough of disillusionment,” as tech builders failed to meet their own deadlines to operate robots in public spaces. Now, robotaxis pick up paying passengers in more and more cities, and automakers make newly ambitious promises about bringing self-driving to customers’ personal cars.

But using a small, agile, and cheap team to get from “driving pretty well” to “driving much more safely than a human” is its own long hurdle. “I can’t say to you, hand on heart, that this will work,” Kentley-Klay says. “But what we’ve built is a really solid signal. It just needs to be scaled up.”

Old Tech, New Tricks

HyprLabs’ software training technique is a departure from other robotics’ startups approaches to teaching their systems to drive themselves.

First, some background: For years, the big battle in autonomous vehicles seemed to be between those who used just cameras to train their software—Tesla!—and those who depended on other sensors, too—Waymo, Cruise!—including once-expensive lidar and radar. But below the surface, larger philosophical differences churned.

Camera-only adherents like Tesla wanted to save money while scheming to launch a gigantic fleet of robots; for a decade, CEO Elon Musk’s plan has been to suddenly switch all of his customers’ cars to self-driving ones with the push of a software update. The upside was that these companies had lots and lots of data, as their not-yet self-driving cars collected images wherever they drove. This information got fed into what’s called an “end-to-end” machine learning model through reinforcement. The system takes in images—a bike—and spits out driving commands—move the steering wheel to the left and go easy on the acceleration to avoid hitting it. “It’s like training a dog,” says Philip Koopman, an autonomous vehicle software and safety researcher at Carnegie Mellon University. “At the end, you say, ‘Bad dog,” or ‘Good dog.’”

The multi-sensor proponents, meanwhile, spent more money up front. They had smaller fleets that captured less data, but they were willing to pay big teams of humans to label that information, so that the autonomous driving software could train on it. This is what a bike looks like, and this is how it moves, these humans taught the self-driving systems through machine learning. Meanwhile, engineers were able to program in rules and exceptions, so that the system wouldn’t expect, say, a picture of a bike to behave like a three-dimensional one.

HyprLabs believes it can sort of do both, and thinks it can squeeze a last-mover advantage out of its more efficient approach. The startup says its system, which it is in talks to license to other robotics companies, can learn on the job, in real-time, with very little data. It calls the technique “run-time learning.” The company starts with a transformer model, a kind of neural network, which then learns as it drives under the guidance of the human supervisors. Only novel bits of data are sent back to the startup’s “mothership,” which is used to fine-tune the system. Only the bits that are changed are sent back to the vehicle’s systems. In total, Hypr’s two Teslas have only collected 4,000 hours of driving data—about 65,000 miles’ worth—and the company has only used about 1,600 of those hours to actually train the system. Compare that to Waymo, which has driven 100 million fully autonomous miles in its decade-plus of life.

Still, the company isn’t prepared to run a Waymo-style service on public roads (and may operate in other, non-street contexts, too). “We’re not saying this is production-ready and safety-ready,” says Kentley-Klay, “But we’re showing an impressive ability to drive with an excruciatingly small amount of [computational work].”

The startup’s real test might come next year, when it plans to introduce its untraditional robot. “It’s pretty wild,” Kentley-Klay says.

The post This Startup Wants to Build Self-Driving Car Software—Super Fast appeared first on Wired.