SPRINGFIELD, Ill. — On a late summer afternoon at the Illinois State Fairgrounds, hundreds of Democrats sipped cold beer from clear plastic “JB” party cups as they waited under a large tent to hear their governor’s fiery populist attacks on President Donald Trump’s agenda.

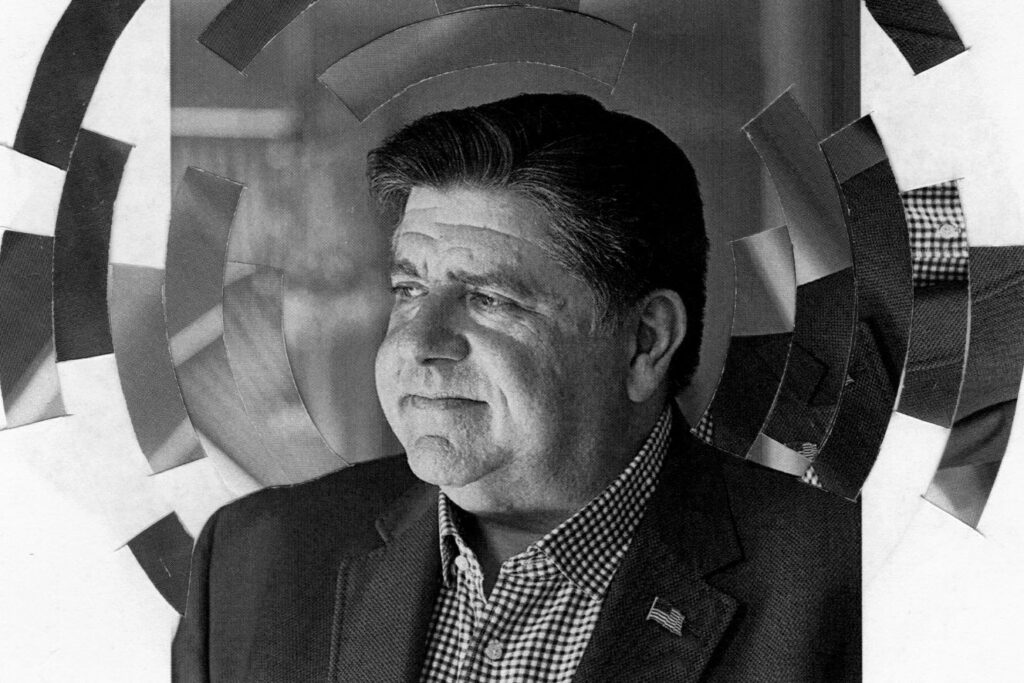

Cutting a broad figure in a casual short-sleeved button-down, Jay Robert “JB” Pritzker, 60, thundered from the stage about Medicaid, Medicare, voting rights, civil rights and food assistance, accusing Trump and his party of demolishing the social safety net.

“MAGA Republicans are trying to take away everything that matters to working families,” said Pritzker, who is seeking a third term next year. “Are you ready for the fight?”

Left unsaid by Pritzker that day in August: He is the wealthiest officeholder in the United States, other than Trump, as a scion of the Hyatt Hotels family with a personal fortune worth $3.9 billion, according to Forbes. For years, Pritzker has bankrolled an array of liberal causes and his own political career at a nearly unrivaled clip, pouring more than $508 million into state and federal elections since 2015, including at least $348 million for his campaigns.

Pritzker’s personal fortune has given him a ready-made war chest that has powered his ascent as a Democratic donor, candidate and officeholder during the past three decades, a close examination of his career shows. His money opened doors to elite fundraising circles and close relationships with Hillary Clinton and other powerful Democrats; instantly turned on a cash spigot in his first run for governor; endeared him to abortion rights activists as he cut checks for ballot measures in a raft of states; and covered the costs of travel on private jets — all without the time-consuming task of dialing other wealthy patrons to donate to him.

To some, that makes him an avatar of a problematic combination of money and politics. Many other Democrats argue that his wealth has given him the freedom to champion policies that benefit everyday people without the constraints of owing favors to donors. For years, Pritzker has fended off rivals in both parties who’ve portrayed him as a “trust fund baby” who has been “buying off” elected officials by presenting himself as an advocate for the working class.

Now, he is using that strategy to lay a foundation for what could be his most ambitious political endeavor yet: a run for president in 2028.

As he forcefully challenges Trump’s agenda on immigration, redistricting, domestic military deployments and the economy, Pritzker is testing his party’s appetite for a leader from the same “one percent” that many have railed against in recent years.

While Democrats have a history of falling in love with charismatic aristocrats who take up the cause of the poor, including Franklin D. Roosevelt and Robert F. Kennedy, this might be a different moment. Left-wing Democrats have increasingly villainized wealth, with Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont) blaming the “oligarchy” for the country’s ills and arguing billionaires shouldn’t even exist, a position fellow democratic socialist Zohran Mamdani, the mayor-elect of New York has adopted. The party that has spent years accusing Trump and his wealthy allies of self-dealing is searching for ways to reconnect with working-class voters that it has lost to Trump’s “America First” appeals.

“I can’t see how a billionaire would be a good person to represent this entire country,” said Carmen Borgia, 26, a graphic designer who carried a sign that said “No such thing as an ethical billionaire” at an anti-Trump No Kings rally this fall in Washington. She said she could not a support a presidential candidate with that much wealth: “They can’t relate to most Americans. It’s just something I am passionate about.”

Other Democrats see Pritzker as the answer to Trump’s brand of populism. “He’s got a really good opportunity to show that not all billionaires are bad,” said Democratic strategist Joe Caiazzo, a former aide for both of Sanders’s presidential campaigns.

Pritzker has for years sought to deflect concerns about his wealth, using a repertoire of self-deprecating lines, a folksy Midwestern persona, an embrace of raising taxes on the rich to help middle-class people and sharp counterpunches. One of his biggest applause lines at the 2024 Democratic National Convention in Chicago — which he helped land for the city after promising Democratic officials that the more than $80 million affair would be debt-free — was that the audience should “take it from an actual billionaire” that Trump was rich in only one thing: “stupidity.”

He drew laughter at a more intimate Nevada delegation breakfast that week after telling delegates that few Illinois voters were looking for a “White Ukrainian American Jewish billionaire” to be their candidate when he first ran for governor in the 2018 election.

A belief in “kindness and empathy in government,” Pritzker argues, distinguishes him from Trump and his wealthiest allies. He points to his push for policies such as forgiving up to $1 billion in medical debt for working-class families and raising his state’s minimum wage to $15 an hour as examples of fighting for those who need it.

“That record, I think, belies the idea that every billionaire is a terrible person or is working against the interest of average working folks,” Pritzker said in a March interview with The Washington Post. “Your policies have to be about the people who need government the most.”

That appeal is being tested as Pritzker introduces himself outside Illinois as one of the most forceful critics of Trump. His pitch has done little to quell the criticism of activists who have raised concerns about the intermingling of money and politics and the barriers less privileged people face to entering public office.

“There’s very few people who can afford to spend even a fraction of the money that Pritzker spent on his campaigns,” said Alisa Kaplan, executive director of Reform for Illinois, a group that advocates for greater transparency and public financing in elections. “You really want a system where that’s your pool of talent for your representatives?”

“I think it’s dangerous,” she said, “because even if you have this exception of the — quote, unquote — ‘good billionaire,’ it’s not a good basis for a political system.”

Early exposure to business and politics

In the Pritzker family lore, the Illinois governor’s great-grandfather looms large. Nicholas Pritzker emigrated from Ukraine to the U.S. in 1881 when he was 10, after he, his father and his brother Abram fled the pogroms targeting Jews in Eastern Europe, according to Pritzker’s account of an unpublished family history written by his great-grandfather.

For their first eight to nine months in Chicago, the family “eked out a mere existence” and the 10-year-old boy slept many nights in the La Salle St. tunnel — avoiding the cold by packing newspapers “around my feet, legs and wrists,” Nicholas Pritzker wrote in another description. That passage was included in a history of the family that a distant Pritzker cousin published in 1962.

“There’s no doubt that I was one of the luckiest people alive,” Pritzker said in a summer interview in the black-walnut-paneled library of the historic governor’s mansion in Springfield, which he and his wife helped restore with $850,000 of their own money. “But it really grounds you when you understand that you came from a family that arrived here with nothing. That it wasn’t always like this.”

Nicholas Pritzker began his career shining shoes and selling newspapers, ultimately going to law school and starting a law firm that his children expanded through the generations into a thriving real estate and manufacturing enterprise, according to court documents and news reports. In 1957, Pritzker’s uncle Jay Pritzker bought a motel near the Los Angeles International Airport. Pritzker’s parents, Donald and Sue Pritzker, moved the family to California to run it. A year later, Pan Am began flying Boeing 707s, ushering in the jet age of business travel. The Pritzkers expanded into other hotels near airports, laying the foundation for what would become the Hyatt Hotels empire.

Pritzker was from an early age a close observer of his parents’ business pursuits, recalling how his mother immersed herself in the design of each hotel — from the experience each guest had walking through the door to the hospitality services offered to VIPs. At home, the family living room was a hub of liberal social and political activity during the 1970s, when his parents welcomed guests including Nancy Pelosi, Jerry Brown and Barbara Boxer, he said.

Pritzker, the youngest child, said he often accompanied his mother to rallies and meetings in the ’70s as she advocated for abortion rights and gay rights. He remembers her sitting him and his siblings, Penny and Anthony, assembly-line -style at the dining room table to stuff envelopes with political literature, seal them and stamp them.

Tragedy struck when Pritzker was 7. His father died of a heart attack at 39 after playing tennis. His mother struggled with alcoholism and depression after losing her husband, Pritzker said. She was in and out of treatment, and he recalled waiting up some nights to pry the lit cigarette from his mother’s hand after she fell asleep. While Pritzker was away at boarding school, his mother died 10 years after her husband’s death, when she leaped from the moving cab of a truck that was towing her Cadillac, according to news reports from the time.

Pritzker went on to major in political science at Duke University and got an early taste of campaigning in North Carolina while he was still in school as a logistics aide for the U.S. Senate campaign of Terry Sanford, a former governor who had served as Duke’s president.

Mark Poole, a North Carolina contemporary who became close friends with Pritzker and would later manage his first run for office, recalled how Pritzker threw himself into the work — driving in his Saab from one end of the state to the other, gathering the concerns of North Carolina voters so he could brief Sanford before each event.

After Sanford won his Senate seat, Pritzker worked in Washington as his legislative assistant. He met his wife, Mary Kathryn — who came from a prominent Democratic South Dakota political family and is known as MK — on a 1988 blind lunch date at a cafe in the U.S. Capitol complex while he was working for then-Sen. Alan Dixon (D) of Illinois and she was working for then-Sen. Tom Daschle (D) of South Dakota, according to a Pritzker spokesperson.

Pritzker showed a continued interest in politics, founding Democratic Leadership for the 21st Century, a group that was focused on bringing more young leaders into Democratic politics, in 1991 while he was a student at Northwestern University School of Law. The internet was taking off in 1993 when Pritzker graduated, and in 1996, he started New World Ventures, a tech-focused venture capital firm that focused in part on Chicago-based start-ups. He avoided taking a job in the family business, inspired, he said, by his father’s example of striking out on his own.

In 1997, when the incumbent retired in Illinois’ 9th Congressional District, which included the North Side of Chicago and had a significant Jewish population, Pritzker saw an opportunity. He entered the 1998 race at 32 with long odds, facing two Democratic opponents with more established political networks. Rep. Jan Schakowsky was then a state representative and Pritzker’s other main rival, Howard Carroll, was a state senator.

Because the Pritzker family business and the Hyatt Hotel Corp. had been headquartered in Chicago, and because the family was involved in philanthropic endeavors, many voters revered the Pritzker name. Pritzker, however, quickly encountered critics skeptical of his thin résumé. Thom Mannard, who managed Carroll’s campaign, recalled a forum in which a student quizzed Pritzker about why “internships” in Washington qualified him to be a member of Congress.

Pritzker often found himself questioning “whether people were in it because they wanted to be in the gravitational pull of a Pritzker or because they were truly loyal to him,” according to Poole, who recalled receiving some asks that were off-putting to Pritzker.

“There’d be a group that would come to us and say, ‘We’d like to honor your candidate as Man of the Year, and it’s only going to cost you $50,000,’” Poole said. “We were trying to cut into what we knew were difficult dynamics with the race — without being seen as buying the election.”

Pritzker raised about $660,000 for his campaign and lent nearly $1.2 million of his own money to the effort, according to campaign finance records, but Mannard said the other two rival campaigns never felt “overwhelmed” by Pritzker’s spending and were surprised that his campaign did not go on air with television ads sooner than they did.

Pritzker finished third in the Democratic primary, with a little over 20 percent of the vote. Inexperience was the central hurdle for Pritzker, Mannard said. “There was a sense that Congress — as the first office that he was running for — it was a bit of a reach,” he said.

Mannard’s former colleague on Carroll’s campaign argued that Pritzker’s wealth has, beginning with that first race, shaped voters’ image of him more than anything else.

“The primary selling point of JB Pritzker — when he first ran for the offices that he ran for in challenger races — was that he has money,” said David Sirota, who was a researcher for the Carroll campaign and later served as adviser to Sanders’s presidential campaign. “It wasn’t like, ‘Oh he’s the guy who did X,’ or, ‘He’s carrying the torch for this or that cause.’ It was like, ‘He’s the guy who can write an unlimited check.’”

‘Does anybody want a wealthy guy on the Democratic side?’

After the loss, Pritzker focused on his venture firm as he and his wife became influential figures in Chicago’s philanthropic circles. The 1999 death of the family patriarch, his uncle Jay, led to the division of the family assets — a lengthy legal process that began in 2001 and ended around 2011. Each of the 11 Pritzker cousins, including JB, inherited $1.3 billion, according to court documents. (He has nearly tripled that fortune, according to his net worth as tracked by Forbes.)

As a couple, the Pritzkers founded the Pritzker Family Foundation in 2001 and put their money into efforts to improve early-childhood education and other causes, which raised their profile in Democratic circles. MK Pritzker became well-known for her advocacy for the rights of women in the criminal justice system. The Pritzkers also advocated for a state assault weapons ban that Pritzker would later sign as governor in 2023.

In 2002, Pritzker and his brother Anthony formed the Pritzker Group, combining the venture firm with the acquisition of manufacturing and industrial service companies, including companies that developed the protective sleeves that slide onto coffee cups and the clamshell containers used to package fast-food burgers.

Politics continued to interest Pritzker. He was an early supporter of Hillary Clinton in the 2008 campaign, at a time when many of his state’s most prominent political Democrats — including his sister Penny Pritzker — were lining up behind then-Sen. Barack Obama of Illinois. The Pritzkers had bonded with Clinton, then a senator from New York, in 2006 after they were connected by a mutual friend and offered to host a fundraiser for her reelection campaign at their home in Evanston, according to his spokesman.

During the event, Pritzker was surprised by how his young daughter was captivated by Clinton, according to an aide familiar with this thinking, who like others spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe private interactions. As he walked Clinton out, she asked to say goodbye to his daughter, kneeling down at eye level to talk to her and hug her, the aide said.

Clinton asked Pritzker to serve as national co-chair for her 2008 presidential campaign. When Clinton ran a second time in 2016, Pritzker and his wife were some of the largest donors to her effort, giving more than $17.5 million, including over $15 million to an allied super PAC. The size of the investment was made possible by a Supreme Court decision that erased limits on contributions to political committees that make independent expenditures, empowering wealthy financiers such as Pritzker.

On the night Trump defeated Clinton, Pritzker and his wife were surrounded by stunned Clinton supporters at her gathering at the Javits Center in New York. While some said they were swearing off politics, Pritzker recalled being even more determined to stay involved.

In 2017, Pritzker decided to challenge Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner, another wealthy businessman who was backed by billionaire hedge fund mogul Ken Griffin, one of Pritzker’s rivals. The state was in a financial crisis, and Pritzker said his allies in the business community nudged him to take on Rauner, seeing him as the rare Democrat with the means to match the tens of millions of dollars of spending by Rauner and Griffin.

Pritzker saw Rauner as a multimillionaire “who was failing the state,” he said during the summer interview, and Trump “was maybe a billionaire failing the country.” He felt he could make an effective working-class pitch to counter Trump’s appeals, which had resonated across wide swaths of the Upper Midwest in 2016.

But he also remembered asking himself: “Does anybody want a wealthy guy on the Democratic side?”

Pritzker entered and ran on a platform of lifting families struggling economically, touting his business acumen and vowing to resolve Illinois’ fiscal crisis — in part by raising taxes on the rich. The state was in the midst of a two-year budget standoff between Rauner and the Democrat-dominated legislature that had resulted in a backlog of more than $16 billion in unpaid bills. To this day, the state faces financial challenges, including significant public pension debt.

His family wealth became a major issue in the 2018 Democratic primary, when Pritzker faced Daniel Biss, then a state senator, and Chris Kennedy, the son of former attorney general Robert F. Kennedy. They targeted the ways that prior generations of Pritzkers had, according to legal documents, sheltered some of the family’s money in about 1,000 foreign and domestic trusts and 250 companies. Pritzker pushed back by noting that the trusts were set up by his grandfather decades ago and involved the assets of multiple cousins and relatives.

“We are in this unique moment in America with massive income inequality, a failed billionaire president, a failed billionaire governor,” Biss said in a debate, referring to Trump and Rauner as he and Kennedy accused Pritzker of trying to “buy an election.”

Kennedy said in a recent interview that those attacks ultimately didn’t land in part because of what he saw as Pritzker’s everyman appeal — which he described as a “lack of arrogance and entitlement” — and an “ability to bond with people immediately.”

“His face is open and it lights up when you meet him,” Kennedy said. “He’s physical. He’s not afraid to hug and to grab somebody with both hands, one on the hand and one on the shoulder, and embrace that moment when he first meets someone.”

In the general election, Rauner accused Pritzker of being a “tax cheat,” pointing to more than $330,000 in tax breaks that Pritzker and his wife sought after purchasing of a $3 million house next to their own on Chicago’s Gold Coast. The Pritzkers removed the toilets and argued the property was “uninhabitable,” prompting criticism from a county watchdog agency, according to documents revealed by local media. Ads from Rauner declared him “Chicago’s Porcelain Prince of Tax Avoidance.”

The Rauner campaign held news conferences with toilets next to the lectern and rented a “Pritzker Plumbing” van with a phone number on the side that would travel through Chicago and other cities when it rained. After dialing the number, people would hear a recorded message accusing Pritzker of taking advantage of the system and warning that he would raise taxes. It signed off with the flushing sound of water going down the drain.

A spokesperson for Pritzker noted that the assessor’s office had found multiple reasons the house was uninhabitable, including mold, structural issues and 2,300 square feet that was not livable.

During the campaign, Pritzker responded to Rauner’s portrayals of him as an out-of-touch plutocrat with ads that highlighted the Republican governor’s nine homes. One spot noted that Rauner had appealed his property taxes nearly two dozen times, questioning why he was attacking Pritzker for doing the same.

Rauner sought to argue that “this is an extremely wealthy man who doesn’t even want to pay the taxes that he owes,” said Ed Murphy, a former adviser to the Rauner campaign. “But it wasn’t enough.”

Pritzker won by nearly 16 percentage points. By the end, he had used more than $170 million of his own money in the campaign.

The spending enabled him to hire some 200 staff, open nearly three dozen field offices and build a 2-1 ad spending advantage over the competition toward the end of the campaign.

Some expenditures still stick in the minds of rival operatives. Campaign finance reports showed the Pritzker team had spent more than $27,000 on Dunkin’ Donuts. “There were just things like that where it was astronomical,” said Betsy Ankney, a Republican strategist who was Rauner’s campaign manager in 2018.

“In any campaign, the budget is a total game of triage and prioritizing” Ankney said. “They just didn’t have to make those tough decisions. If they wanted to do something, they did it.”

Clashing with Trump and venturing beyond Illinois

After taking office, Pritzker spearheaded an ultimately unsuccessful ballot campaign to change Illinois’ tax structure that would have given him more freedom to raise taxes on the wealthy, contributing $58 million of his own money to the ballot campaign and urging voters to tax people like him more. (Griffin once again served as his chief adversary, spending nearly $54 million to defeat Pritzker’s proposed amendment).

The governor’s legislative moves had pleased liberals: The first big bill that he pushed through the legislature with Democratic lawmakers after being elected governor was to raise the state’s minimum wage from $8.25 an hour to $15 an hour.

After spending $152 million on his reelection bid, Pritzker easily won a second term in 2022. He drew accolades for addressing the state’s fiscal stalemate after a budget impasse, reducing the backlog of state bills and notching credit upgrades for Illinois.

As he runs for a third term as governor of Illinois, Pritzker has pushed off questions about whether he will run for the White House in 2028 but has also said he won’t rule it out.

In recent years, Pritzker has sharpened his focus on causes beyond Illinois. After the Supreme Court in 2022 overturned Roe v. Wade, which had guaranteed a constitutional right to abortion, he founded the tax exempt nonprofit Think Big to promote access to abortion and advance ballot measures enshrining abortion rights in states attempting to restrict them.

The Illinois governor seeded the group, which is not required to reveal its donors, with his own money. In its filing for the 2024 fiscal year, the most recent available from the IRS, Think Big reported $6.8 million in revenue. The group contributed more than $3.6 million to abortion-related causes, the filing showed.

Pritzker also vowed to make Illinois a safe haven for abortion, in part because it was surrounded by states that have restricted the procedure. In 2023 and 2024, Think Big contributed to abortion rights groups that were advancing ballot measures in nine states including Ohio, Nevada, Arizona, Montana, Nebraska and Florida, spending millions on ads, organizing campaigns and mailings. They were on the winning side in seven.

Pritzker has been an unusual “partner,” said Mini Timmaraju, the president of Reproductive Freedom for All, one who has helped her organization think through strategy on ballot measures and gotten directly involved in the field work.

“They’re not just writing checks,” Timmaraju said. “They’re getting in the states. Their strategists are working hand and glove with our staff in all these places.”

As part of Pritzker’s effort to bolster abortion rights and other Democratic causes, Pritzker and his wife have personally given at least $9 million to state Democratic parties since 2015 — both in battlegrounds that determine midterm and presidential races and red states such as Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky and Ohio. Of the $348 million Pritzker contributed to his first two gubernatorial campaigns, he disbursed more than $60 million to other candidates and political committees to help lift Democratic candidates, according to an analysis of campaign finance records.

Some say they see a troubling dynamic resulting from Pritzker’s wide net of political investments.

“He’s used the money to build political relationships for himself,” Sirota said. “If somebody’s been funded by JB, or been helped by JB, will they help him because they feel sort of an obligation? There’s the other layer of somebody’s been helped by JB — and if they don’t help him, they’re not going to get any more help in the future, right?”

Pritzker has deployed his wealth in other ways that have drawn attention. He has supplemented pay increases for his aides. And he used his personal and campaign funds — $4.5 million of the latter from 2017 to 2024, according to records — to pay for flights on private jets for political and official business.

Pritzker’s wealth came under a renewed spotlight this fall when his campaign released tax summaries revealing $1.4 million in blackjack winnings from a 2024 trip to Las Vegas. His office said he would donate his recent winnings to charity.

This year, Pritzker has sought to introduce himself to audiences in some early presidential states. In April, he fired up a room of hundreds of Democrats in New Hampshire, tearing into Trump for what he called his “authoritarian power grabs” and castigating those in his own party who believe they can “reason or negotiate with a madman.”

Pritzker’s scathing attacks on Trump and “do-nothing” Democrats have attracted attention in the party — especially because he started them in the days after Trump’s election, when other top Democrats, such as California Gov. Gavin Newsom and Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, were still counseling caution or voicing hope that they could work with Trump.

Before the New Hampshire speech, more than a dozen Democrats in the room said they knew little about Pritzker beyond his wealth. But many left with a positive impression.

“Maybe it’s even nice to have someone who can pay for his own campaign, then the rest of us don’t have to pay for it,” said Patrick Long, a 37-year-old attorney from Manchester.

Howard Wolfson, a longtime adviser to former New York mayor and presidential candidate Mike Bloomberg, a billionaire who self-funded his short-lived 2020 Democratic presidential campaign, predicted that Pritzker’s wealth “will be a barrier for some voters.” But he added: “In a time when there is an enormous amount of corruption in government and concerns about special interest power, the idea that you have somebody who is free and clear of that is potentially very attractive to some people.”

Trump, who has built a national movement with many working-class supporters, has frequently attacked Pritzker, insulting his weight during the annual White House turkey pardoning and suggesting earlier in the fall that he should be “in jail” for his treatment of federal immigration agents. The administration launched an immigration enforcement operation in Chicago in September as part of a crackdown on violent crime and illegal immigration.

This summer, when Trump first talked about deploying the National Guard in Chicago, Pritzker called the president “a bully” with “dementia.” He mocked Trump’s dark descriptions of his state by playing the role of vest-wearing combat zone correspondent “reporting from war-torn Chicago” on “Jimmy Kimmel Live!”

Teri Ricci, a 65-year-old retired university employee from Carbondale, Illinois, said she initially had no interest in backing “just another gazillionaire,” but ended up volunteering for Pritzker’s gubernatorial campaigns.

“He’s not in it for the money. He’s already got the money,” Ricci said in an interview at a Pritzker campaign event this summer as he launched his reelection bid. The first time Ricci heard him speak, Pritzker told the crowd that the good thing about having a lot of money was that he was not beholden to anyone.

“That’s what sold me,” she said.

Read the Billionaire Nation series

- How billionaires took over American politics

- The forgotten court case that let billionaires spend big on elections

- How George Soros changed criminal justice in America

- The top 20 billionaires influencing American politics

- We asked 2,500 Americans how they really feel about billionaires

About this story

Reporting by Maeve Reston. Additional reporting by Clara Ence Morse, Beth Reinhard and Aaron Schaffer. Photography by Theo R. Welling and Joshua Lott. Illustration by Tucker Harris. Illustration contains prop paper money.

Design and development by Tucker Harris. Design editing by Betty Chavarria. Photo editing by Christine T. Nguyen. Editing by Nick Baumann, Patrick Caldwell, Wendy Galietta, Anu Narayanswamy and Sean Sullivan.

The post The Democrat testing the appetite for a leader from the ‘one percent’ appeared first on Washington Post.