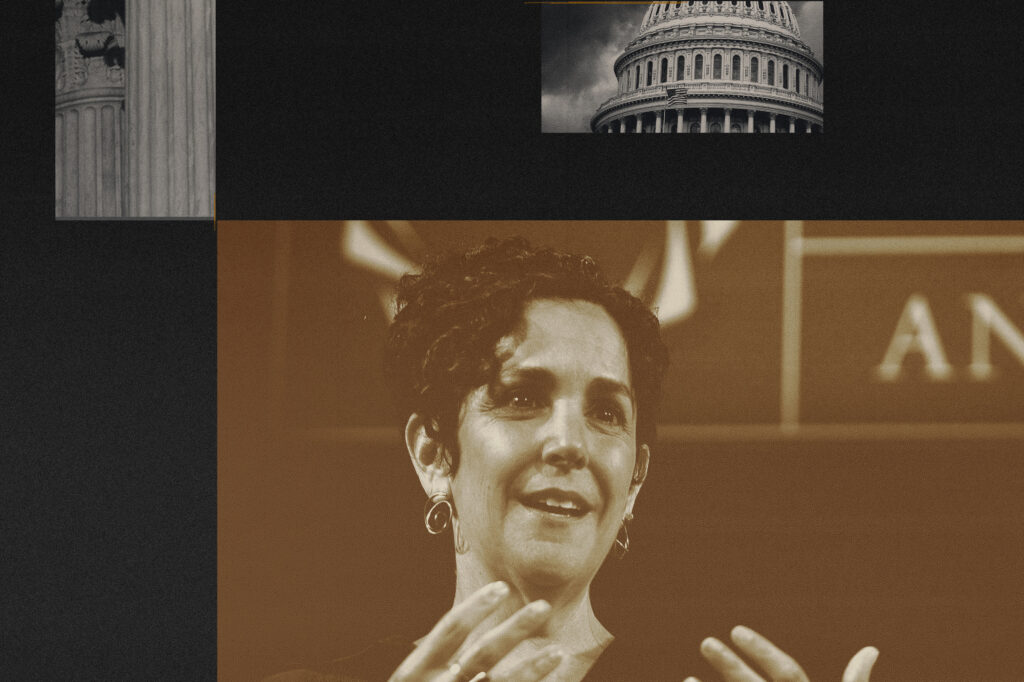

Yaël Eisenstat didn’t expect her career to completely unravel after publicly accusing her former employer of profiting off propaganda.

Eisenstat, Facebook’s former head of election integrity, alleged the social media platform allowed political operatives to mislead the public with sophisticated ad-targeting tools in a 2019 op-ed. Meta has argued that these ad policies were to prevent censorship of political speech.

Soon, she said, former colleagues started gossiping about her. It was hard to find a new job. Eisenstat said she would routinely interview with senior managers who would later ghost her. One institution courted her for months for a leadership role but then told her they wouldn’t hire her. That day, the organization announced a major donation from the philanthropic organization of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan.

Eisenstat never thought Meta’s CEO was purposely torpedoing her job prospects, but the timing made her feel discouraged.

“I knew it, like, in my gut … I had been blacklisted,” said Eisenstat, now the director of policy and impact at the Cybersecurity for Democracy research center. “You just start to feel paranoid because no one will say to you ‘This is why we will absolutely never interview you or call you or speak with you.’”

She lived off consulting projects while she waited for a full-time job. It took her four years to land something that matched the rigor of her role at Facebook, the company now known as Meta.

Eisenstat is part of a growing group of former tech workers who have alleged that their Silicon Valley employers harmed the public and compromised users’ safety. This cohort of whistleblowers has triggered a public reckoning over the technology industry, including a slew of negative media stories, heated congressional hearings with top tech CEOs, and a steady stream of laws around the world that ban or restrict social media use for young people.

This year alone, at least nine current or former Meta employees have come forward with a litany of claims, including Sarah Wynn-Williams who wrote a best-selling book alleging company leaders went to extraordinary lengths to court the Chinese government, perpetuated sexual harassment and turned a blind eye to the ways its platforms could harm users.

Meta has argued that Wynn-Williams’s allegations about China were “no secret,” that an investigation found her allegations of harassment were unfounded, and that she was fired for poor performance.

But many whistleblowers say coming forward has unexpectedly derailed their lives. They say they became isolated among their colleagues, suffered severe professional damage, or were pushed out of the industry altogether. For a generation that entered Silicon Valley with a sense of idealism, viewing tech giants as mission-driven organizations seeking to improve the world, the cold reception to what they consider truth-telling has come as a shock.

The biggest corporations are increasingly playing hardball against employee critics. Earlier this year, Meta won an arbitration ruling against Wynn-Williams that bars her from promoting her tell-all memoir or saying anything “disparaging, critical or otherwise detrimental” about Meta, including in private remarks to her husband or children, according to Ravi Naik, Wynn-Williams’s lawyer.

Meta’s ongoing legal challenge could limit any professional or financial success she gains from the book, and the company is seeking “at least tens of millions of dollars that she obviously does not have — simply for telling her story,” Naik said in a statement.

Louise Haigh, a U.K. politician, testified in Parliament in September that Wynn-Williams was facing a fine of $50,000 every time she breached that gag order.

“Sarah has repeatedly alleged she is being pushed to financial ruin through the arbitration system in the U.K.,” Haigh said. “She is now on the verge of bankruptcy.”

Meta spokesman Andy Stone said in a statement that Wynn-Williams had not yet been forced to make any payments under the agreement. He added that sharing information with U.S. regulators or testifying truthfully under oath are legally protected activities. “This should not be confused with former employees publicly making false or misleading claims about a company, in which case they alone are responsible for the consequences,” he said.

The throng of tech whistleblowers has spurred few tangible changes to the industry’s practices. Last year, the Senate passed a pair of bills to expand online privacy and safety protections for children but the measures stalled in the House. A bipartisan push to pass laws to limit tech platforms’ market power didn’t get a vote in the Senate in 2022.

“It can often be a struggle for them to remind themselves that ‘my disclosures are really important but the world’s not gonna stop spinning overnight,’” said Jennifer Gibson, founder of Psst, a nonprofit that offers whistleblower support, particularly in the AI industry.

From Edward Snowden to Jeffrey Wigand, whistleblowing has historically come with steep personal and professional costs. Snowden, a former National Security Agency employee who leaked top-secret information about U.S. surveillance programs, has been living in exile in Russia; Wigand, a biochemist who exposed how the tobacco company Brown & Williamson manipulated the nicotine in its cigarettes, faced death threats and a lawsuit from his former employers.

“The reality is that often they’re not able to secure similar employment in their industry ever again, and they have to make huge pivots,” said Margaux Ewen, the director of the whistleblower protection of the Signals Network, which supports whistleblowers in a wide range of sectors. “They may struggle to secure an academic position or a fellowship … And so it really is a huge decision that has far reaching consequences”

Arturo Béjar, a former Meta consultant, urged Zuckerberg and other top executives to better address the bad experiences young users were having on Instagram. In an email, he told Zuckerberg that his daughter and her friends had been harassed since they were teenagers — a phenomenon he reported was backed by data. Zuckerberg didn’t respond.

“I realized that I was protecting Mark Zuckerberg and the company and I wasn’t really protecting the people who … I dedicated most of my life to,” he said. “And then [in] that moment — it flipped for me.”

Before coming forward, he had relied on savings from Meta, which he joined before the company’s IPO, while he spoke to the Wall Street Journal and testified before Congress. But when he put out a call for new engineering and policy consulting clients a year after he went public, no one asked for his services.

It was “the first time in my life that’s ever happened,” he said.

These days, Béjar said he continues to live off his savings and feels burdened about paying for two children’s college tuitions. But he finds satisfaction in explaining the safety risks of technology to media outlets, regulators and civil society groups. Béjar said he has no regrets about coming forward.

“I can sleep at night now. I really wasn’t sleeping well with what I knew,” he said.

Regulators are beefing up legal protections for would-be whistleblowers, particularly those interested in exposing the dangers within the artificial intelligence boom. In September, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law a bill expanding protections for some tech employees working at companies developing leading AI models who want to expose “catastrophic” risks. In May, a bipartisan group of senators introduced the AI Whistleblower Protection Act that bars AI companies from retaliating against employees who report security vulnerabilities or violations to regulators. Meanwhile, a crop of whistleblower organizations such as Psst.org, the Signals Network and Whistleblower’s Aid have emerged, offering legal and emotional support for employees who want to speak out.

Not every whistleblower faces the same risks or career fallout. By the time Frances Haugen — who in 2021 leaked internal research on the harms of Facebook and Instagram — decided to come forward, she said she had amassed savings after years of working at Google and Meta and a cushion from some savvy crypto investments.

She watched YouTube videos of people living out of vans to reassure herself she could make a living. “If you write software, you have a certain level of freedom — you’re not going to go hungry,” she said.

In Haugen’s case, her public profile grew. She wrote a book, launched a tech-policy nonprofit and began booking speaking engagements. Living now with her husband in Puerto Rico, she said, she has also fielded a stream of job offers, including from several start-up social networks.

Some former colleagues were supportive of her privately but seemed hesitant to associate with her publicly. Others felt betrayed that she had criticized the safety work at a major tech company, essentially “biting the hand that fed them,” she said.

“I had folks who flat out came up to me and just let me know ‘I disagree with what you did.’ I appreciated them telling me to my face,” she said. But “I wasn’t prepared to be as ostracized from within the trust and safety industry as I was.”

Navaroli’s career also shifted. She became an assistant professor at the Columbia School of Journalism, where she teaches students about tech policy. It is a role she said she finds “incredibly meaningful” despite the fact that it doesn’t pay as much as she would likely be making in the tech industry.

Sometimes Navaroli asks herself whether becoming a whistleblower was worth it. Since her testimony, billionaire Elon Musk bought Twitter, now known as X, and reversed or weakened many of the company’s policies barring hate speech and misinformation. Trump’s accounts on every single major social media platform have been restored. And a quarter of Americans believe an unfounded conspiracy that the FBI instigated the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Then she remembers she never expected drastic changes to come from her testimony. Instead, Navaroli said her aims were smaller: sharing the truth with the public.

“I genuinely don’t think I would have been able to live with myself if I didn’t do what I did,” she said. “And I now get to figure out how to live with myself doing what I did.”

The post Tech whistleblowers face million-dollar debts, job loss and isolation appeared first on Washington Post.