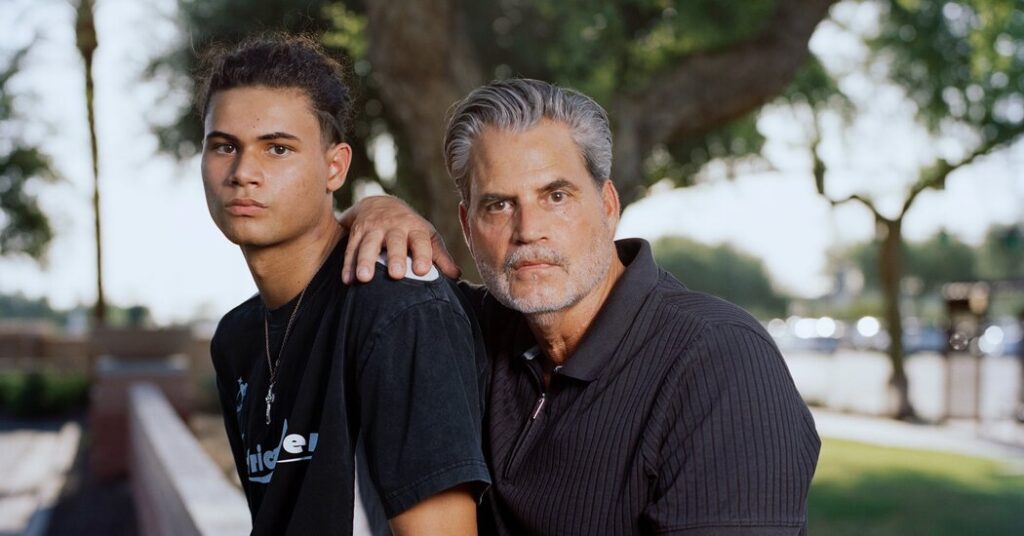

Nearly five years ago, on a brisk night in November, Rick Kuehner opened the door of his Arizona apartment to find a uniformed cop standing outside. Next to him was a smaller, slighter figure: Rick’s 14-year-old son, Tristan. As Tristan did his best to look anywhere but at his father, the officer explained that earlier in the night, the police had apprehended two teenagers for trying to break into cars parked at SanTan Village, a nearby shopping center. One boy was a high school student already well known to the police. The other was Tristan.

Rick was dumbfounded. He and his son lived in Gilbert, an affluent town in what’s known as the East Valley, a rumpled tract of desert that extends roughly from the outskirts of Phoenix to the foothills of the Superstition Mountains. The schools were good, the median income was high and crime rates were low — all reasons he had chosen to move to Gilbert in the first place. “And here was Tristan, somehow managing to get wrapped up in something stupid anyway,” Rick said. “Getting himself escorted home by the cops.”

Still, he was not without sympathy for the boy. In addition to the pressures of class work and competitive swimming (Tristan was a member of the varsity squad at Gilbert’s Campo Verde High School), Rick knew that his son was still processing his divorce from Tristan’s mother, Terry-Ann, and Terry-Ann’s decision to move with her new husband to the west side of Phoenix.

So instead of issuing punishment, as his own parents might have done, he secured a promise from Tristan that he would stay away from his friend. “In my opinion, kids deserve a chance to learn from their mistakes,” Rick recalled. “That’s how you grow up.” Ultimately, Tristan was never charged with a crime, and Rick resolved to put the incident behind them.

This turned out to be easier said than done. In the coming days, Tristan and his friend became embroiled in a heated exchange. Tristan, the friend believed, had snitched on him to the police. In fact, it had been Rick who pointed a finger at the other boy. “I gave them a statement saying, basically, that Tristan had been pressured into it,” Rick said. “I thought the cops should know that. I was being a good dad, you know? I was trying to protect my son.”

On Nov. 19, 2021, two weeks after the encounter with the police, Tristan was approached by the friend at a school bus stop near his apartment. According to one teenage witness, the boy challenged Tristan to a 60-second fistfight. Tristan made a counterproposal of 15 seconds; they settled on 25. Tristan took several punches before being shoved into a bush. Bruised and bleeding from scratches on his arms, he managed to reach his phone and call his father. “I got there and Tristan is splayed out on his back,” Rick recalled. “He couldn’t move his body. I had to carry him to the passenger seat of my car. It was clear that this was escalating in a frightening way.” He drove Tristan back to their apartment, where the boy was interviewed by the Gilbert police.

In a report, an officer wrote that he asked Tristan “why he didn’t just walk or run away rather than agree to fight.” He replied that his friend was “faster than him and he would have chased after him and assaulted him anyways.” In a separate conversation, the officer interviewed the friend’s mother — the friend had been recently detained at a juvenile detention center in Phoenix for a different infraction. She wasn’t sure when he would be out, but she was planning to enroll him in a military academy.

Worried, Rick arranged a sit-down with the principal of Campo Verde, who assured him, Rick says, that Tristan would be safe on campus, given that the other boy was no longer enrolled at the school. (A spokeswoman for Campo Verde declined to comment over concerns of student confidentiality.)

In December, the officer concluded that the two boys “had entered into mutual combat. With this, I do not have probable cause for assault.” The case was designated as inactive.

Still, word circulated at Campo Verde that Tristan was a snitch; Rick believes that his son’s friend went so far as to urge other students to retaliate. A few weeks later, on the eve of a big swim meet, Tristan was attacked in the school bathroom and beaten severely. Arriving at the school, Rick was escorted to the nurse’s offices, where Tristan was waiting, his neck and shoulders purple with bruises. Rick held his son and let him cry. “It’d be easy for me to say now,” he said, “with all the trials and media attention, that I understood what was happening at Campo was bigger than either me or Tristan.”

But in those confused early days, Rick could not yet see that his son was being pulled into an increasingly common form of modern teen bullying — one in which harassment spills chaotically between the schoolyard, the street and in online interactions often indecipherable, or entirely invisible, to adults. Nor did he understand that what he assumed to be isolated incidents were actually part of a pattern of escalating violence involving members of the Gilbert Goons, an informal street gang since linked by the police to numerous assaults across the East Valley. By the time the group’s activities were brought to light, years later, the entire community would be consumed with recriminations over the apparent inability of officials to stop it sooner. And a 16-year-old boy, Preston Lord, would lie dead, allegedly killed by seven Goons, six of whom are scheduled to go on trial in early 2026.

Already, Lord’s death has stoked national outrage and the ire of anti-bullying advocates; it has also inspired a bill, signed into law in May by the Arizona governor, that, in part, stiffens criminal penalties for any participant in a group attack on a single individual. “Preston’s memory has been a rallying cry,” the boy’s stepmother proclaimed at an Arizona senate committee hearing, “not just for justice but for prevention.”

And yet to Rick Kuehner, who has grown close with the Lord family, and who has cheered the passage of what’s known as Preston’s Law, his experience is a vivid demonstration of how difficult it can be to keep your child safe, even for a diligent parent. “To me, this is a story about responsibility,” Rick told me. “Because I did everything I was supposed to. I filed the right reports. I talked to the right people. I notified the right authorities. And no one paid attention until it was far too late.”

By his own admission, Rick had little frame of reference for what was happening to his son. Rick had loved high school — he considered it to be the happiest period of his life. “I played football and basketball, I had friends, I had great teachers,” he said. “It was like ‘The Breakfast Club.’ When I think about it now, that’s what I picture.” Which wasn’t to say he didn’t know bullying when he saw it, or that he wasn’t familiar with the most immutable law of teenage social code: that a bullied kid, having been exposed to his peers as weak, will often be revictimized again and again, unto infinity — or until school officials intervene.

In late 2021, Rick again approached administrators at Campo Verde with concerns about Tristan’s safety. Again, he says, he got the requisite assurances. He knew that school staff are what’s known as “mandatory reporters”: Under Arizona law, if school personnel have “reasonable belief” that injury or abuse is taking place, they are obligated to document it. He allowed Tristan to return to Campo Verde.

This, he acknowledged, was “probably a mistake.” The East Valley comprises more than a million residents and hundreds of schools: When the authorities later combed through reports on teenage violence from that time period, they were able to locate a handful of accounts of on- and off-campus harassment among East Valley students, but little that revealed the true and awful extent of the issue.

In many cases, parents and teachers seemed to have dismissed the incidents that were documented as isolated — or at least as no different than what high schoolers had experienced for decades. “I don’t want to let anyone off the hook, or to allege that folks here don’t take bullying seriously,” said a person who works closely with several East Valley school districts, and who was not authorized to discuss the matter publicly. “But you have to be realistic about what it’s like for teachers on the ground. These are staffers facing insane turnover, shrinking resources and campuses that are getting more and more crowded — and they’re being asked to deal with every problem that comes their way: Kids showing up high. Kids skipping school. Guns. Violence. It’s like trying to fend off a thousand paintballs at once.”

On his first day back at Campo Verde after the bathroom fight, Tristan was working out in the student-athlete gym when he was approached by a few acquaintances. “They were like, ‘You work out — why didn’t you fight back?’” Tristan said. “I was so embarrassed. Everywhere I went, people were staring, laughing.” Fearful of escalating the situation further, Tristan forbade his father from intervening again. “I had my parents. And I had swimming. I figured as long as I was on the team, as long as I was competing, I could figure out a way to shut out the noise.”

The harassment continued anyway, at a low and persistent hum. “People kept pressing me,” Tristan said — poking and prodding him to see if he would explode. Walking down the hallways, his gaze focused on the floor, he heard the other boys mutter taunts of “pussy” and “little bitch.”

At night, Rick would sometimes find his son huddled under his covers, crying. “You want to talk about heartbreaking, about the things that will tear you open inside — it’s that,” Rick told me. “After a while I was like, ‘OK, how about we get you a transfer?’” He mentioned Perry High, in neighboring Chandler. Perry, he reminded Tristan, had a strong swim team. Plus, Tristan’s oldest friend was enrolled there. The summer after sophomore year, Rick submitted a transfer application to school board officials and Tristan was approved.

But the East Valley, despite its size, is the sort of community where rumors tend to travel fast, and Tristan’s reputation seems to have been cemented long before he walked through the front doors of Perry High. That fall, after he started his junior year, Tristan received a Snapchat message from an old classmate at Campo Verde.

“Do you go to Perry?” the teen asked.

“Yes bro,” Tristan wrote back.

“My friends wanna jump u already there,” he wrote.

“Huh. Who,” Tristan typed.

“I ain’t telling you.”

Tristan protested that he knew hardly anyone at Perry, but the boy ignored him. “They said u got a big mouth,” he went on. “And u getting urs.” He uploaded a photo, presumably a selfie, of himself hunched over a handgun and a bag of ammo. “What’s up?” he wrote.

As soon as Tristan returned home, he showed the messages to his father. “I grabbed the phone and went straight to the school,” Rick recalled. “They sat me down with the vice principal and the school resource officer” — a uniformed and armed law enforcement officer assigned to Perry High. “I said: ‘Please. You’ve got to listen — there’s something really bad happening here,’” he went on. “I wanted everything on the record.” But according to Rick, there was never any follow-up from the school. (A district spokeswoman declined to comment on specifics, saying, “The district does not tolerate bullying, harassment or intimidation in any form.”)

In the absence of intervention from officials, the threatening messages continued to flood in. By now, two Perry students, including a boy named Mason Lander, had also joined in.

Rick approached the school with a proposal: Perhaps he could speak directly to the kids’ parents. Rick was aware that administrators wouldn’t be able to give out their phone numbers, though surely they could forward his information. “The district superintendent was on vacation, and a different guy emailed back and said, ‘I passed along your info,’” Rick said.

A week later, while Rick was taking the dog on a walk, Tristan texted him to say that two cars had pulled up outside the house. Tristan was terrified. “Not only had these kids figured out my address, they had gotten through the security gates,” he said. While Tristan waited for his father to return, his phone buzzed with a picture of his own car in the driveway. “Implying, like, We know you’re in there,” Tristan said. “So I texted my dad to warn him.”

Turning the corner at a run, Rick recalls spotting the two cars at the curb. He pulled out his phone to take video, but once the cars’ occupants saw him approach, they fled.

That night, two Gilbert police officers drove to the Kuehners’ house to take a statement. To prove to the officers that his son was the victim and had nothing to hide, Rick told them they could look through Tristan’s phone.

Holding up the device, one officer pointed to an invitation that Tristan sent earlier that day to Lander and his friends: “Pull up right now,” it said. “I’ll [expletive] you up.”

Tristan protested that he was merely hoping to get a group of bullies off his back — to make a stand. In his mind, he had been trapped in an impossible situation: Ignore the cascade of threats, and his silence would be interpreted as an invitation for the harassment to continue.

“You can’t be instigating things like that, though,” one officer shot back, according to bodycam footage from that night. “You can’t say that.”

“Bro,” Tristan said. “I was just angry, bro.”

“You gotta shut up,” his father responded.

The officer continued scrolling, stopping to read another message from Tristan: “If you have a gun and you’re gonna point it at somebody,” he wrote, then they’d better be ready to “use it or not.”

“See, that’s stupid,” Rick cut in. “That’s a stupid thing to say.”

“Yeah,” Tristan admitted.

“You’re trying to be such a tough guy,” Rick said. “You be smart, and you — you stay outta that [expletive]. I’m telling you, man. I’m 57 years old. I have good advice to give you.”

Collecting himself, Rick got back to his original point. Yes, his son may have acted provocatively. But he had endured verbal and physical abuse. Tristan was the target here.

The officers said Rick could consider applying for an injunction, a type of court order often used to help prevent ongoing harassment. But to obtain one from a municipal judge would require confirming the names of the occupants of the cars — and at the moment, all they had to go on was Tristan’s testimony. (One officer later reached out to a school resource officer to corroborate some of Tristan’s claims about his harassers. It’s unclear what the S.R.O.s did with that information.) “I’m just gonna write up kind of the gist of what I have,” the officer explained. “Like I said, I’ll do some — a little bit of digging to see if I can identity any of the names he gave me, but, um … ”

He gave Rick a business card, a case number, and left.

Rick felt as if he were trapped in some kind of terrible feedback loop. Once again, he believed he was doing what a parent was supposed to do when a child was bullied — he had alerted the school, he had alerted the police. He had “checked all the right boxes,” as he put it. And once again, he was being told, effectively, to sit tight. “I totally understand that these things can take time. I know it’s not as simple as someone swooping in and stopping it,” Rick recalled. “But I was left sitting there, knowing it wasn’t a matter of if these kids were going to get Tristan. It was a matter of when.”

A year before, Rick might have considered sending Tristan to the West Valley to live with his ex-wife, but Terry-Ann was now in Europe. “The solution I settled on was to have Tristan come straight back to the house every day after practice,” Rick said.

But Tristan chafed at the arrangement. “I was cooped up inside,” he said, “and everyone else was out driving around, partying.” On Aug. 18, 2023, Tristan emerged from his bedroom and begged Rick to allow him and a friend to go grab a burger. Rick relented. “I said, ‘Just this one time, and you guys have to be back here in 30 minutes,’” he said.

Sometime after 10 p.m., Tristan arrived at the In-N-Out Burger in SanTan Village, a popular East Valley hangout and the same mall where, two years earlier, he had been picked up by the police for attempted burglary. The lot was full — other East Valley teenagers milled around, clustered in small circles, laughing. Tristan parked, and he and his friend headed toward the entrance.

“I remember turning and barely having time to figure out what was happening,” he told me. “I just knew there was a truck behind me and that a bunch of kids were piling out.”

In an account later provided to the police, an 18-year-old named Aris Arredondo said he had been summoned to the In-N-Out by Tristan’s schoolmate Mason Lander, who Arredondo understood was feuding with Tristan. Arredondo admitted to exchanging a few heated words with Tristan but claimed he backed off after Tristan began retreating away from the In-N-Out.

The rest of the incident was captured on camera by an onlooker: “Which one of y’all homies want it, too?” thunders Arredondo. He walks away as Tristan is surrounded and tossed to the ground. A few of the boys aim kicks at his head, while two others try to pull off his sneakers.

“Yo,” a voice says from off-camera. “Chill, bro.”

Lander then enters the frame, although it’s unclear from the footage if he’s trying to break up the fight, as he would claim in a police interview, or get in on the beating.

“Somehow I got up and crawled back to my car,” Tristan recalled. He drove the half-mile to his home and fell through the door with a crash, startling Rick. “I couldn’t even see his face,” Rick said. “It was so covered in blood.”

He took a few photos of Tristan’s injuries and told him he was calling the police. Tristan jolted upright. “No,” he said. “They’ll kill me. They’ll kill you, too.”

Dialing 911, Rick learned that officers were already at the In-N-Out. Shortly after 11 p.m., a uniformed officer arrived at the Kuehners’ house, followed by an E.M.T. Tristan’s mouth was “bloody and swollen, his clothes were stretched and dirty, indicating signs of a struggle,” the officer noted in his report. “Due to the swelling of his jaw, he was limited in how far he could open his mouth to speak to me.”

“I want to press the fullest charges to the maximum extent,” Rick remembers saying.

Tristan Kuehner’s time at Perry High School had come to an end. That much was obvious. Through August and early September, Tristan was a “nervous wreck,” Rick recalled. He rarely slept, and he stayed in his bedroom for days on end, accepting meals through a narrow crack in the door. “If you so much as approached him, he’d jump like 10 feet in the air,” Rick said. “He was constantly talking about how bad the scars on his lips were, and how he’d need plastic surgery.”

In the evenings, Rick worked his computer and phone, begging for updates. “Am I ever going to hear back from anyone?” he texted the officer who interviewed him on the evening of the assault. But investigators were having trouble making progress, police records show: The subjects of the video, one court filing says, “were not able to be identified” by the S.R.O.s at high schools in the area.

Records indicate that the police did speak with Mason Lander, his father, Theodore, and his stepmother, Jamie, who at the time was the principal at Riggs Elementary School in Gilbert. “During an interview, M.L. acknowledged he was at the In-N-Out restaurant and spoke with the victim but denied assaulting him,” a court filing reads.

As proof, Mason shared the video of the incident, which had been uploaded to Snapchat. He was only briefly visible in the clip, he pointed out. Noting that Mason’s hands were free of bruises, the officers left.

In early September, Rick told Tristan to go to Europe to be with his mother. “I hated having to say those words out loud,” Rick told me. “But there was nothing else I could think of doing.”

Then came the incident that would connect Tristan’s case to a larger epidemic of bullying in the East Valley. In late October, news broke of the fatal assault on 16-year-old Preston Lord, who was attacked by several peers outside a Halloween party in the desert town of Queen Creek. Preston was knocked down, kicked and punched repeatedly in the head. After his assailants fled, other partygoers attempted to perform C.P.R.; approximately 48 hours later, doctors at a nearby hospital pronounced him dead.

“I remember we published something on the Lord death, and right away we got an absolute flood of community tips — people across the East Valley coming out of the woodwork to say that they had info to share,” Ashley Holden, a television reporter with an ABC affiliate, told me. “And a lot of the rumblings had to do with a group that called itself the Gilbert Goons.”

Many of the teenagers reportedly came from wealthy families, dealt drugs and carried guns. Anyone could label themselves a member, or, with equal facility, disavow their association — there was no official swearing in, no hierarchy, no leaders.

Holden’s first instinct was to go straight to the Gilbert police, who she reasoned must have a dossier on the organization. “I remember going with a cameraperson and parking myself in the lobby of police HQ, and saying, ‘I’m not leaving until the chief talks to me.’”

But the Gilbert police had yet to connect all the dots. As is increasingly common in cases involving bullying or teen violence, many of the incidents subsequently attributed to the Goons involved exchanges that took place via text, social media platforms or video game chat logs visible only to the participants. Even when investigators were able to obtain a warrant for the information, says Jim Bisceglie, an assistant chief for the Gilbert police, “sometimes the data is already gone from Company A or B or C by the time it’s sent over to us. It’s piecemeal, and you’ve got the complexity of reading through all the messages, trying to understand the order.”

Or what’s being said at all. “The way teenagers speak today — it’s almost like they all have their own little codes and languages,” says Michael Soelberg, the chief of police in Gilbert.

Equally vexing was the question of jurisdiction. In Arizona, minor arguments in the classroom are handled by administrators or security guards, while more serious incidents are delegated to an S.R.O.; trying to discern the root causes of a physical fight required conversations with different authorities, none of which had the full picture.

Patrick Banger, the town manager of Gilbert, said that in a perfect world, parents of teenagers would be responsible for “enforcing accountability.” To say: “You have to be responsible for your own actions, who you associate with, and involve me when you need me involved.”

Easier said than done, not least because of the unwillingness of most teenagers to talk with their parents, and the reluctance of administrators to facilitate parent-on-parent meetings, which can escalate tensions.

After Lord’s death, Soelberg told me, he asked several members of his department to go back and review two years of police reports, looking for instances in which parents had raised concerns to city officials or the police. “What we ended up finding is that in a lot of the cases, kids never told their parents what was happening,” he told me. “Or if they did, those parents didn’t inform us or administrators.”

“What frustrates me is that even if the police claim they weren’t able to put together all the pieces quickly enough, for whatever reason, there were plenty of us out there who had done exactly that, without the tools law enforcement has at its disposal,” Katey McPherson, an East Valley youth advocate and parent, told me recently. McPherson often says that her “calling in life is to be very, very noisy, especially about things that other people would prefer to stay under wraps.”

In 2019 and 2020, she helped draw attention to a succession of teen suicides that horrified residents of the East Valley — and which McPherson depicted, in interviews and at rallies, as a result of inaction on the part of city officials and school administrators. A few years later, inspired by the news about the Gilbert Goons, she convened a group of residents, most of them other East Valley mothers, to track down as much information as possible about the activities of the new gang.

“It ended up not being very hard to do,” she told me. “You took a name from a news story on an assault, and you went on any popular social network. And you could see that these kids were tagging each other in videos or posts about a bunch of different attacks.”

As she had done with the youth suicides, McPherson shared the information with various authorities, including school officials and the police, and received little traction. She also met with the parents of teenagers who claimed they’d had run-ins with the Goons. One of those teenagers was Connor Jarnagan. In 2022, 10 months before Lord’s murder, several people now suspected of being Goons threatened to steal Jarnagan’s Ford Mustang coupe and smashed him in the back of the head with a pair of brass knuckles. (“Didn’t even fight back … I just beat his ass after he wouldn’t let me steal his car,” a boy later bragged to several of his friends in a Snapchat message. “Only thing I wanna see is the world burn.”)

When the police proved slow to make an arrest, the Jarnagans appealed directly to the public for help. Their willingness to speak openly about Connor’s assault marked a rupture in the silence that had settled over the East Valley: Other parents and students started to step forward, each with a distressingly similar story. “I’d gotten almost used to not being believed, but remember reading about Connor and feeling a chill go down my back,” Rick told me. “Because he’d been attacked at the In-N-Out Burger where Tristan was beat up.” (In fact, he would discover, the restaurant had been the backdrop to a number of teen assaults.) “Once I put it all together,” Rick went on, “I was ready to keep fighting, pushing. And I could, because now Tristan was safe overseas.”

One evening in the fall of 2023, Rick went on Nextdoor, the neighborhood-based social networking site, and typed a description of Tristan’s assault, adding that he believed the attack at the In-N-Out had been perpetrated by the Goons. The community needed to “stand up,” he wrote. “I am blessed my son is alive, but so many other kids have been less fortunate.”

McPherson reached out to him the next day, and she and Rick began corresponding. She could be a resource for him, she said: Together with the other mothers in her circle, she had managed to identify the boys involved in Lord’s death before the police published their names. (In addition to the six who are awaiting trial for murder, one has already pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of manslaughter and was sentenced to 12 years in prison.) Rick sent her all the information he had.

It didn’t take long for McPherson to identify, with parent friends, the names of some of the participants in Tristan’s assault at the In-N-Out. “But there was no action,” she told me. “Our kids were sitting in class next to the ones responsible, and no one was doing anything, and it was getting tense. Like: Should we let our kids go outside? Can they go safely to the mall or a bonfire? What’s going to happen?”

Rick later met with the parents of Connor Jarnagan and Preston Lord, who gave him the validation he had been seeking for more than two years. He wasn’t alone — he hadn’t lost his mind. In extensive interviews with reporters across the East Valley, Rick took to railing loudly against the police for ignoring a clear and present danger in their midst. “They could have had all this stuff done months ago,” he said in one exchange with a reporter from The Arizona Republic. Had the authorities done so, he went on, his son would still be home, and Preston Lord would still be alive. He made a point of attending school board meetings, community rallies.

“You could basically see the pressure building on authorities to do something,” McPherson recalled. “It was like, OK, finally — people are stepping forward to demand action.”

In late December 2023, two months after Lord’s death, the Gilbert police posted screenshots from the video of Tristan’s In-N-Out Burger attack and asked for the public’s help in identifying the subjects. Within days, investigators were inundated with tips, which led them to three juvenile suspects and two 18-year-olds: Christopher Fantastic and Aris Arredondo. In an interview at police headquarters, Arredondo denied hitting Tristan but said he “flinched” at him, “after which multiple other subjects then assaulted the victim,” according to one court filing.

Arredondo went on to implicate Deleon Haynes, a 19-year-old East Valley resident who told the police he had hit the victim “two or three times with open palms.”

But Haynes refused to name any of the other participants; Christopher Fantastic invoked his rights to ask for an attorney. And Mason Lander, who appears briefly in the video from the In-N-Out Burger assault, was no longer as forthcoming as he had been: “Your superiors want you to find somebody right now,” Jamie Lander, his stepmother, told a detective. Mason, she said, was just a “scapegoat.” (The Landers did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Once more, Gilbert detectives found themselves wading through a sea of digital content, searching for clues to the motive behind the attack, and the identities of any other potential participants. Still, in January, they amassed enough evidence to bring to Rachel Mitchell, the Maricopa County attorney. Mitchell, in turn, assigned her own investigator to look into the In-N-Out case, warning him about what she had learned from her involvement in the Lord case. That file alone, she told me, contained more than 600 pieces of digital media, including dozens of videos, and a 2,000-page police report. “That’s like ‘Hunt for Red October’ times five,” she said. And from that evidence, she added, you needed to understand the background and context of the conflict.

Mitchell and her staff announced that a grand jury had indicted Fantastic, Haynes and Arredondo on assault charges; all three subsequently pleaded guilty and were sentenced to probation and community service. (One juvenile assailant also received probation and community service. Lander and another juvenile suspect were not prosecuted “due to no likelihood of conviction.”)

But the Landers have faced more scrutiny: Last year, the family became one of the targets of a civil suit brought by an East Valley mother named JoBeth Palmer, who claimed that in May 2023, Mason Lander and a few friends descended upon Palmer’s teenage son at a park in nearby Mesa. “As somebody began pushing him from the front,” another person picked him up from behind “and slammed him into the ground,” the complaint says. He was then “punched and kicked by multiple assailants.” Realizing he wasn’t prepared to fight back, they left, later uploading a cellphone video of the attack to social media. That same week, Mason sent Palmer’s son a Snapchat message: “Keep tryn hit my girl up n watch yo ass get stomped in again,” he wrote.

In addition to Lander, Palmer’s lawsuit, which has since been settled, named four other participants in the assault, including Fantastic, who was arrested for his role in Tristan’s attack, and Jacob Pennington, a self-professed Gilbert Goon currently awaiting trial for the murder of Lord.

“I still talk to Preston Lord’s dad,” Rick told me in August. We were parked near Perry High School, a complex of squat brick buildings foregrounded by a parched strip of sand. A few teenagers milled around in the courtyard. One was carrying a skateboard. Rick studied them. “I try to support him,” he said, “but it’s hard, because it’s like: ‘Man, your son is gone. Mine isn’t.’ I can’t imagine that feeling.” He removed his sunglasses and rubbed distractedly at the bridge of his nose. “Of course, in a different way — a very different way — my son is gone, too, you know?” he sighed. “It’s not like he’s in another state. I can’t take a short flight to see him. And here I am, missing the crucial years of his life, when a kid needs his father. I feel like I’ve let him down.”

The sentencing of the participants in the In-N-Out assault have helped, he allowed. “Still, I’ll be honest: It doesn’t feel like enough,” Rick told me. He and his attorneys filed a lawsuit against 17 former East Valley students and 26 of their parents or guardians, who are described in the suit as liable for their children’s campaign of “willful or malicious conduct.” The filing is purposefully broad: It names the perpetrators in the attack on Tristan, as well as Jamie and Theodore Lander, but also teenagers like Jacob Pennington, the defendant in the Lord case.

Although Pennington has not been accused by law enforcement of directly attacking Tristan, he and others are part of what the suit calls a conspiracy to “commit assault and battery on innocent and unsuspecting teenagers.” (Separately, Rick has sued local school leadership and the Gilbert Police Department for $6 million for engaging in a pattern of “gross negligence” and for failing to protect Tristan and others.) But the lawsuits have not provided Rick the closure he hoped for — while some of the defendants have chosen to settle, several of the claims, including the one against the Landers, have been dismissed.

“I truly believe that if parents had gotten a grip on what was going on through 2022 and 2023 — if the schools had, if the police had — Preston Lord would still be alive,” Rick told me. “If you’d had arrests, that would have been a deterrent. It would have sent a message.” Instead, he continued, “sort of the opposite thing happened: A kid died, and then everyone woke up.”

To Rick, the underlying issue was one of “reactivity versus proactivity” — a phrase I heard him use often. “You had the city and the schools essentially sweeping this stuff under the rug,” he said. “Hoping it would go away. Hoping it was just kids being kids.”

It was understandable that Rick would want to frame it that way — a neat, clear-cut interpretation of a series of events that were anything but. But the story was considerably more tangled and convoluted, in a manner that could be repeated in other jurisdictions, with other kids. The circumstances that led to the brief epidemic of teen violence that ensnared Tristan are not unique: police with limited knowledge of how teens interact, parents unsure of what’s going on, overworked school administrators struggling to get a grip on harassment that seeps between digital platforms and the schoolyard.

Tristan, for his part, seemed to grasp this. “I don’t hold anything against the kids who beat me up,” he told me recently. “I forgave them.” That forgiveness extended to Rick, and his feeling of failure: “I know if anything happened to my kid, I’d definitely be really angry,” Tristan said. “And I know my dad did his best. A lot of people around me did their best, you know?”

This year, Tristan quietly returned to the United States to spend the summer in Gilbert with his father and his friends; he has also enrolled in a state university. “What I want most of all is for Tristan to have the youth that was ripped away from him,” Rick told me. “I want him to get to be a teenager, to be a college student, to experience what other kids get to experience.” For that reason, he added, Tristan is going by a different first name. “It’s what he deserves: to put everything behind him,” Rick added. “To forget the past and start over.”

The post He Tried to Protect His Son From Bullies. He Didn’t Know How Far They Would Go. appeared first on New York Times.