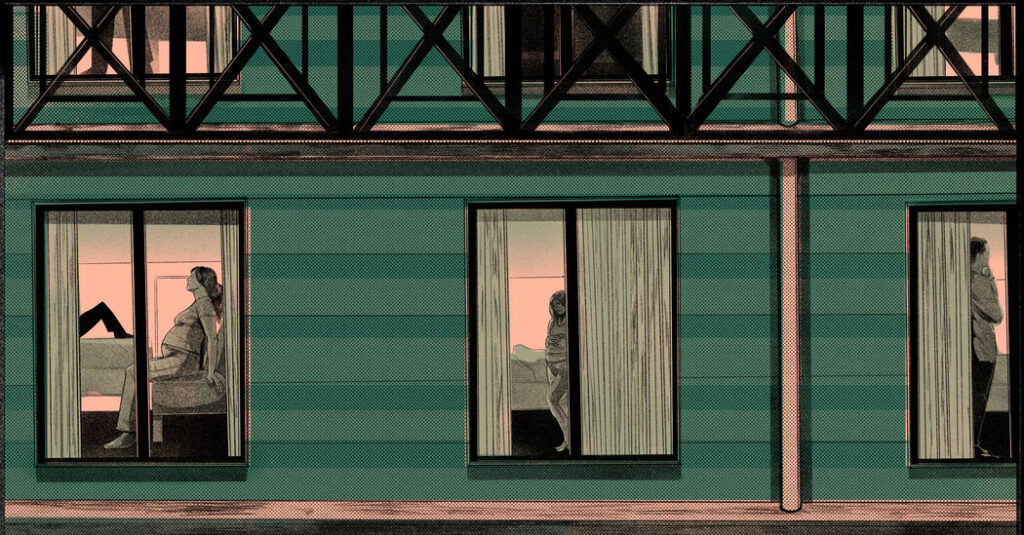

The women in House 3 rarely had a chance to speak to the women in House 5, but when they did, the things they heard scared them. They didn’t actually know where House 5 was, only that it was huge and perched somewhere outside Tbilisi, on one of the many hills that surround the Georgian capital. They heard that there were hundreds of pregnant women in House 5, crammed many to a room. They heard that there was limited food in House 5’s communal kitchen — the pork, rice and vegetables their bosses were supposed to provide daily were in short supply — and so the women of House 5 had to fight one another for vegetables or go hungry.

When the women from House 3 saw the women from House 5 at the fertility clinic, they looked fierce. They sat in the waiting area with their legs crossed and their arms folded. Intimidating. Maybe, they told themselves, those House 5 women had to be that way to survive. They heard that in House 5, they kept their cooking oil in their own rooms, not communally as they did in House 3, where whoever wanted to could use it. The women in House 3 also heard that if a woman in their house misbehaved, broke the rules, didn’t take her fertility medication on time, talked back or tried to run away, the bosses of House 3 would sell her to the bosses of House 5. Then, her troubles would really begin.

If any woman in any of the five houses wanted to leave, if she was unhappy in Tbilisi, thousands of miles away from her home in Thailand, if she missed her family or changed her mind about her decision to board a plane, often for the first time, to travel far from her own children to work as a gestational carrier, a surrogate mother — a mae um boon, as they called her in Thai — for the Chinese-run operation that boarded and fed her, she could not just simply tell the bosses that she no longer wanted to become pregnant and birth babies for strangers, that she wanted to go home. In addition to paying her own way back, she had to reimburse the bosses for what they claimed she had cost them. That price was at least 70,000 baht ($2,200).

But the women had come to Georgia because they did not have this kind of money to begin with. And so, a woman who wanted to leave really only had two choices: She could ask for money from her family or friends — most of whom were themselves poor and had no idea where she was, or what she was really doing — or she could sell her eggs. If she sold her eggs three times, she could earn enough to pay back her debt to the Chinese bosses and buy a ticket home. The women of House 3 heard about a woman in House 5 who did this. They also heard that afterward, she got a bad infection and almost died.

More often than not, the women didn’t want to enter into that kind of arrangement. They just wanted to get an embryo transfer, have a baby, make their money and go home. But the longer they stayed, the more confusing things became. When they tried to ask even the most basic of questions — What was in all this medication? Where were these babies going? — they couldn’t get any answers. The doctors just ignored them. It was as if their bodies were not their own.

‘A Mother Who Carries Merit’

Eve ended up in House 3 because of her father. For years, she had been working to cover the family’s debt, taking out one loan to pay the interest of another. Then her father had become sick with osteomyelitis, and by the time he was admitted to the hospital, the 73-year-old couldn’t move the bottom half of his body. Doctors said he would never walk again, but he worked hard to defy their prediction. After he was discharged, he went straight back to selling fruit from his large metal cart. But between the two of them, it was still not enough to cover the interest and rent on the small room the family shared in a ramshackle wooden house among the warren of narrow roads on the outskirts of Bangkok.

When she was small, Eve hadn’t dreamed of becoming anything in particular — just rich. Not even rich rich, just stable rich. She wanted to have her own house and her own car. She wanted enough money so that her father would stop pushing his fruit cart. He raised her and her younger brother alone, after her mother took her to kindergarten one morning and vanished. Eve watched for years as her father divided the one meal he bought each day into three portions for himself, so he could afford to feed her and her younger brother and buy their school uniforms, shoes and books. Eve left school and started working at 13 to help him. Even though Eve believed her father favored her brother — only nodding when she handed over her earnings, never saying she was good — she loved him unconditionally.

Now, by 24, Eve had been a construction worker, a driver, a restaurant manager, a masseuse, a security guard, a housekeeper and the sole woman stocking heavy things in a warehouse. She studied for a high school equivalency exam and passed. She tried her hand at being a pastry chef and finished a government-funded Thai massage course. Her favorite job, though, had been as a waitress: She loved small talk, taking care of the table and helping customers pick out food that would please them. Most recently, she had worked as a motorcycle delivery driver, known as a rider in Thailand.

When the debt collectors came after Eve, she could handle it. But then they came after her brother. The 20-year-old did little to help the family, somehow unable to hold down a job long enough to get a paycheck. Eve had left his name as her guarantor, but she never expected them to post his real name and photograph online with threatening messages: “If anyone sees this dickhead, please let me know. I will pay.” The family stopped sleeping at home and spent their nights dozing in game parlors. They could sneak into their room only at 1 or 2 a.m. and leave again by 3 or 4 a.m.

The Facebook post she saw seemed innocuous enough:

I’m looking for a woman to work in Georgia. Legally. Income 500,000-530,000 baht. Age range: 20 to 35.

“What kind of work is it?” Eve messaged the account. “Do I have to go over there? Or is it in Thailand?”

The account replied immediately and explained the job was to be a surrogate. Eve would have to pass a health check in Bangkok — a blood test and a transvaginal ultrasound — fly to Georgia and pass another health check there; she would then get 10,000 baht ($310). After that, she would have someone else’s embryo transferred into her uterus and receive another 10,000 baht. Eve would get 20,000 baht when the doctors detected a fetal heartbeat, a monthly payment of 20,000 baht during the course of the pregnancy, then the remainder of the money when she delivered a healthy baby.

Eve had never heard of Georgia, a tiny, mountainous country of 3.7 million that borders Russia, Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan, and she had only vaguely heard of surrogacy. Though she did not have any children, the more she thought about it, the more she thought being a surrogate could be a nice way to help people. (Mae um boon literally means “a mother who carries merit.”) But more than anything, Eve was thinking about the money: 530,000 baht is roughly $16,400, which, while not exactly a life-changing sum, would clear the family’s debt and allow them to start over.

Last October, four days after answering the ad, Eve checked into a hotel room in Bangkok in preparation for the health check. Her roommate, Eye — a 21-year-old from an impoverished eastern region along Thailand’s border with Cambodia — had responded to an identical post. (Because of fears of stigma and retaliation, Eve, Eye and the other Thai women in this article are being identified by their nicknames.) The night they met, Eve and Eye started talking and didn’t stop. Eve was a big talker, always trying to fill the silence. She was tall and broad for a Thai woman, so she often hunched over, squeezing her shoulders together self-consciously, as if trying to hide. Eve loved American movies with morals about persevering through discrimination, poverty or social cruelty — “Green Book,” “The Help,” “Forrest Gump.”

For her part, Eye was vivacious, sarcastic and pretty; her nickname came from her distinctively shaped eyes that seemed to brim with mirth, as if she were always on the cusp of laughter, possibly at someone else’s expense. Eye loved Black American pop culture, listened to rap, made TikTok videos she didn’t post, curled her hair and wore fake braces — a fad in Thailand. For a while, she had been underemployed at a factory, but then she lost the job completely. Her mother had taken out a loan to buy a motorbike, then another loan against the same motorbike; then she got sick. Eye understood it was up to her to take care of them. After she sent her personal details to the Facebook account, the account connected her to someone she was told was already working as a surrogate in Georgia. That woman told Eye that she should pack her own fork, a knife and an electrical adapter. She said everything in Georgia was great — she was pregnant. Neither Eve nor Eye had told their parents the truth about where they were going.

As Eve and Eye talked, they found that in their previous attempts to earn money, they had each been trafficked to Bahrain with the promise of massage work that turned out to be “dirty.” They agreed the situation Eve had faced there was more difficult. Eye had to get customers to buy drinks at a bar and was occasionally forced to have sex with them, while Eve’s brothel recruited men online who would come to the discreet location and choose a woman from among those standing in a large room. They would then go into one of three back rooms, about the size of closets, and she would typically give him a blow job or have intercourse with him. After a woman got 10 “shots” — ejaculations — she could go home for the night; otherwise, she had to stay until 3 a.m. Women had to work off their “debts” to get their passports, then they could choose whether or not to stay. Some did: They were making money, and a camaraderie developed between them and the newer women. They were nice to Eve and sometimes bought her dinner.

Neither woman was naïve about the risk she was facing. They knew from experience that there were plenty of bad situations a woman could end up in answering a call to work overseas: places where a woman was brought for farm work, but where her passport was held and she was beaten, or to be a house cleaner who was then raped, or internet scam centers where women were tortured, even killed. Bad things happened. Each job came with its own trade-offs; perhaps Georgia would be no different. Sitting in their hotel room, they asked each other: Could this paycheck really be so easy?

Living ‘Like a Family’

Over the next few days, five more women joined Eve and Eye at the Bangkok hotel. The agent who would travel to Georgia with them, a woman who went by Bee, gave them instructions. She told them to install WeChat, so they could communicate with their Chinese bosses once they arrived in Tbilisi, and sent around a packet of documents to show if they were stopped by immigration, including a phony daily tourist itinerary, a return flight on Qatar Airways, fake hotel bookings and travel insurance. Bee told the women to bring as many Thai cooking ingredients as they could, explaining that they were either hard to find or expensive in Georgia. So the women crammed small bottles of fish sauce, galangal, lemongrass and makrut lime leaves into their luggage. None of them had been anywhere cold before. Eve had seen fake snow at an amusement park in Bangkok and couldn’t wait to see the real thing.

Bee explained what would happen once they got there: The women would live in rented accommodations, two or three to a room, “close together, like a family.” She showed them pictures on her phone of brightly colored rooms — orange, green and pink walls that seemed recently renovated — with new twin beds and nice furniture. They would take “hormone balancing medication” for one to two weeks, she explained, and then they would get an embryo transfer. The parents would be gay couples or people who could not conceive easily. Bee never mentioned where they would be from, and the women never asked.

The morning of their flight, they left the hotel at 3 a.m. They arrived in Tbilisi that evening and were taken to a derelict hotel called 2Floors, which stood at an intersection on a sloped street. There was nothing nearby that the women could see — no supermarkets, no restaurants, no kiosks or corner stores. Thailand is often referred to as a land of abundance, not just in terms of lush agriculture and produce, but also the ubiquity of 7-Elevens, food stalls and shopping malls. By comparison, Georgia seemed grimy, small and sparse.

Bee took them upstairs. She explained that the bosses lived on the ground floor — a Chinese couple who went by Joe and Cindy, along with their baby and Cindy’s parents.

Several Thai women came to huddle with Bee, exchanging news. One of them perked up when she heard Eye’s name.

“Who is Eye?” she exclaimed.

Eye raised her hand.

“You are my girl,” the woman told her. “If you have any problems, let me know.”

The woman’s name was May, and Eye quickly understood this was whom she’d spoken to about knives, forks and adapters. For recruiting her, it soon became clear, May was receiving a commission — 35,000 baht ($1,000), paid in installments, spread out over the milestones of the recruit’s successful pregnancy.

May had told Eye on the phone that she was pregnant, but looking at her, Eye didn’t think she was. Eye and Eve stole furtive glances at all the gathered women’s bodies — none of them seemed to be pregnant as far as they could tell, though they knew their whole paycheck depended on this.

Many things were not quite what they expected. The rooms were dingier than they had looked in the photos; the bed frames were older or entirely missing, and there were few blankets. Eve had packed a small blanket, but gave it to Eye when she saw her friend shivering. Eve pulled on all three of the sweaters she had brought, but she was still cold.

The next day, May came to their room to collect their passports. When Eve asked why, May explained that some previous recruits had run away after receiving the first 10,000-baht payment for passing their health checks. Eve and Eye handed over their documents without protest.

A Shifting, Spreading Global Marketplace

The global fertility industry has evolved by breaking procreation into different components — creating chains of reproduction, step by step, piece by piece, assembled to result in a baby. Moving parents, donors, eggs, sperm or surrogates around regulations is so routine, there is a name for it: reproductive tourism. This has led to all kinds of elaborate arrangements for the creation of children. In Georgia, intended parents from China can import Ukrainian eggs or semen from Denmark, create embryos in Tbilisi and use Thai wombs to bear and birth babies before bringing a child home to Shanghai.

The industry is often likened to the Wild West, but it’s more complicated than that — less a totally unregulated space than one where privilege affords the opportunity to route around regulations. With deep enough pockets, anything is possible. “The fertility market is incredibly flexible,” said Andrea Whittaker, a professor of anthropology at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. “Depending on your citizenship as an intended parent, some companies offer to arrange what combination you can do, so that you can have a set of legal procedures to circumvent whatever local laws there are.”

The market the industry has evolved to serve is colossal: Infertility is believed to affect almost 200 million people of reproductive age worldwide, but some estimates range as high as one in six adults. Some women are born missing ova, while up to 3.7 percent lose ovarian function before 40 because of genetic abnormalities or cancer treatments. As many as one in 4,000 women is born without a uterus, while others have congenital problems or go on to develop conditions that can affect their ability to carry a baby, like excessive fibroids, hysterectomies, severe endometriosis, heart conditions, autoimmune disorders, complications from previous C-sections and more. Half the couples who struggle to conceive are affected by male infertility, which can result from testicular trauma, very poor sperm quality or many other causes. And most statistics on infertility don’t include those characterized as “socially infertile,” like same-sex couples, or single people who need medical assistance to become parents. One growing segment of the market is those who see fertility treatment as a way to unshackle women from the biological expectations put on their bodies.

People facing infertility are rarely told having a child is impossible; instead, they are offered a variety of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), whose efficacy is often limited at best. As far as medical treatments go, the success rate of in vitro fertilization is abysmal — roughly one in four I.V.F. cycles globally results in a live birth. (In the United States, the rate is only slightly better: a little more than one in three.) The University of Cambridge sociologist Sarah Franklin has called ART “hope technologies,” precisely because they promise so much while creating a different kind of uncertainty, leading many to undergo copious futile treatments in an attempt to chase the yearning that comes out of a deep sense of despair. As a result, the market is only expanding — various research firms estimate that, a decade from now, it will be worth nearly $100 billion. Private equity considers the industry downturn-resistant: There is only a limited time to pursue treatment, and people are willing to mortgage their houses to try.

Over time, clear global hubs have emerged for particular parts of the trade — the United States is the hub for white-glove commercial surrogacy, Denmark for sperm, Spain for eggs. The industry’s development has always been global. In 1978, the birth in Britain of the first I.V.F. baby showed that embryos created outside the body could be carried to term, opening up the possibility of “gestational surrogacy,” in which a third party bears a child to whom she is genetically unrelated. The first live birth from a donated egg took place in Australia in 1983, while the first reported case of gestational surrogacy happened in Ohio in 1985.

Differing regulations across the world on ART push families to travel in pursuit of their desires. Germany, Switzerland and Turkey ban egg donation, though “donation” itself is a confusing term. Some countries, like the United States and Ukraine, have commercialized gametes, allowing the market to set the price of a woman’s decision to sell her eggs or a man to sell his sperm. Others, like Britain and Australia, allow only altruistic donation, in order to discourage what they otherwise consider to be organ trafficking. Much of the E.U. and Scandinavia has outlawed surrogacy; last year, Italy made traveling abroad for it punishable by a two-year prison sentence.

Rules around gamete-donor identity differ from country to country: In America, parents can choose a named donor and remain in touch with them throughout the child’s life. Some countries, like Britain, allow the child to request their donor’s details when they reach adulthood, while others, like Spain, mandate donor anonymity. Policies on the testing and storage of embryos also vary; in Poland, for example, destruction of viable embryos is a criminal offense, and after 20 years of storage unused embryos are donated to other couples.

These regulations have given rise to a spreading, shifting global marketplace, as consumers travel for their preferences and their budgets. In the 1990s, India became the undisputed hub of commercial surrogacy; the country legalized the practice in 2002, as parents also flocked there for low-cost I.V.F. packages. But over time, scandals mounted — reports of abused and unpaid surrogates, sick or abandoned babies and mixed-up embryos — and in 2012, India began to regulate the practice. So, the industry adapted, hopscotching to Thailand, Mexico and Nepal, all of which soon experienced their own controversies. After a 2015 earthquake stranded dozens of Indian surrogates and newborns in Nepal, Israel airlifted 26 babies, leaving the surrogates behind; Nepal banned the practice soon afterward. India and Thailand banned commercial surrogacy for foreigners in 2015. In 2016, Cambodia followed, as did the sole state in Mexico that had allowed it, completely cutting off the trade.

The market reconstituted in Russia, which became popular with intended parents, particularly from China. In 2015, the Chinese Communist Party amended its one-child policy to allow all married couples to have two children, while the collapse of the Russian ruble, coupled with the rising incomes of China’s growing middle class, made Russia an attractive destination. The demand for Asian eggs there grew so great, women were often stimulated locally — in Thailand, Taiwan, China or Kyrgyzstan — flown to cities in Russia, operated on and then sent back on a plane. After a surrogate-born baby died of unknown causes, Russia banned commercial surrogacy for foreigners in 2022, leaning heavily on tropes of “traditional values.” That same year, the country banned egg donations in surrogate pregnancies for its own citizens, pushing Russians to join the throngs of couples seeking treatment abroad.

After the Russian market closed, the influx adapted again, flowing into Ukraine, which had already attracted intended parents from America and Europe after it legalized the practice in 2002. Ukraine, home to a population of 41 million rife with blue-eyed blondes — the ultimate stereotypically desired phenotype — quickly became a hub of both eggs and surrogacy, with nearly 3,000 donor cycles and more than 2,000 children born to surrogates each year before the war. Unlike many other countries, Ukraine amended its regulations in 2013 to prohibit women from selling eggs or being a surrogate unless they already had one healthy child. The change was primarily a marketing gimmick guaranteeing the donors’ or surrogates’ “proven” fertility, but it also happened to protect against some of the medical and ethical concerns tied to participating in these markets, including future infertility.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in the middle of the night in February 2022, leaving foreign parents stranded far from their infants, the tiny former Soviet state of Georgia experienced an avalanche of interest. The rush was overwhelming. The country simply did not have enough wombs, so clinics and agencies began importing them. On any night in Tbilisi, it’s possible to see clusters of heavily pregnant women — from Kenya, Ethiopia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Ukraine — treating themselves to a meal from their regional restaurant or going to the supermarket. The industry calls them “traveling surrogates.”

The Rules of House 3

It didn’t take long for the women in the houses to grasp the contours of their new life, the unspoken rules of the house and its routines. The first step in the process was a trip to a fertility clinic for a health check. The clinic Joe and Cindy brought Eve and Eye to, LeaderMed, was on the other side of the city. The initial exam was painful, prodding. The medical staff who carried it out — nurses, doctors, the women couldn’t tell — didn’t speak to them or explain anything. Eve assumed it was just the way it was there. Joe and Cindy referred to one room in the clinic as their “office.” Inside, there was a sofa and a table with nothing on it; outside were chairs that the women were often told to sit in and stay silent, not to talk to the other women they saw there. When the women passed their health checks, they received the first 10,000 baht and were told to wait for their periods. As soon as the money hit her account, Eve sent it to her father.

Eye was the first of the newly arrived women to get her period. In standard surrogacy protocol, starting from the second day of her menstrual cycle, a surrogate takes hormonal medication to prepare the lining of her uterus to mimic the body’s natural changes each month. After about 20 days of medication — whether pills, patches. injections or suppositories — the endometrium should thicken to the correct degree. Next, an embryo is loaded into a catheter and guided into her uterus with the aid of ultrasound. After the transfer, the surrogate continues to take medication to help implantation occur and for the pregnancy to progress. Nine days after the transfer, a blood test can verify whether she has successfully become pregnant. But none of this is possible until her body responds to the medication.

When Eye returned from LeaderMed, she had a photograph of a protocol written in English — white pills she was supposed to take until her next appointment. Then she started injections. Eye didn’t speak English, and there was no one who spoke Thai at the clinic to teach her how to administer anything. So, Eve set about managing Eye’s medications by watching videos online.

As more women got their periods, went to the clinic and came home with instructions, Eve began to help them too. Waiting to bleed was boring, and being helpful was something to do. Eve finally got her period a few weeks later, when the whole house was in the process of moving to another defunct hotel called AIA, so everyone forgot about her. They eventually brought her to the clinic on the fifth day of her period, too late to start a cycle, and so it would be another month before she had the chance to try again. It was only after her next period started that she was brought back and given white pills to take.

Preparing for an embryo transfer was tedious — going to health checks, taking pills, doing injections, inserting suppositories. If they were going to the clinic, they had to leave early, but those visits were relatively infrequent. Otherwise, they woke up whenever they wanted, went down to eat — someone made communal rice — cleaned up their breakfast, went upstairs to clean their rooms, took a nap, watched movies, YouTube, TikTok, made dinner, cleaned up and went to sleep.

The days blended together. Eve passed the time folding and refolding her clothes. Sometimes she cleaned the bathroom, just for something to do. She had turned what happened to her in Bahrain into a funny story and liked to tell it to the other women to pass the time. Eve hated the stillness, the routines in Tbilisi. She took to wandering into the other women’s rooms, trying to make them laugh. Sometimes she caught herself wondering: Am I really laughing, or is this just something I’m doing to pass the day?

Bee was in and out, traveling back and forth from Thailand to bring in new groups of women. In her absence, she seemed to have delegated responsibility for monitoring the women to a few surrogates she was close to, including May, whom Eve and Eye nicknamed C.E.O. At AIA, as it had been at 2Floors, there were locks on the doors and keys in the locks. There were cameras in the hallways and stairwells, and downstairs in the kitchen. The women were told not to leave the house, but they had no reason to leave, anyway. They worried about being stopped by the police, especially as they didn’t have their passports. They weren’t sure whether what they were doing was truly legal: Hadn’t they lied to immigration on the way in? Besides, going anywhere required money, and they had little to spend. After their initial payment for passing the health check, they would get nothing until they had an embryo transfer, and they had no idea when that would be.

Eve learned that AIA was part of a group of five houses in Joe and Cindy’s network, which was supplied by two different networks of Thai agents. The houses were referred to by number: House 1 was 2Floors, where Joe and Cindy still lived. House 2 was a different house somewhere in the old city, while House 3 was AIA. House 4 was for the big Chinese bosses, where the babies were taken from the hospital to rest until their parents came for them. (No woman Eve spoke to had seen the baby she birthed or the parents she supposedly birthed it for.) House 5 was the large house on the hill.

When they moved into AIA, there were already women living there. One of them was the first pregnant woman Eve met. Eve quickly inquired about how the woman had gotten her embryo transfer. “I waited for a long time,” the woman said. “When the right day comes, they do the implantation.” But after weeks of medication, Eve was growing increasingly concerned. She didn’t know why she kept being sent home with more white pills — just that her body wasn’t ready for a transfer. The longer she went without payment, the more lies she told her father. “The job isn’t working out.” “The payment is delayed.” “My boss took money from my salary to cover my ticket.” At her appointments, the doctors didn’t explain anything. Eve started trying to earn on the margins. She took out other women’s trash for tips, she ordered food from a Thai restaurant and manipulated the exchange rate (undercutting May, who was doing the same thing).

Joe sent around a numbered list of rules: Gossiping or discussing wages was forbidden, passports had to be relinquished and Cindy would collect a 10,000-baht fee for any procedures that were necessary to prepare their uterus for transfer, like polyp or fibroid removal. For anyone who broke a rule, there were “punishments.” And so the information came in dribbles — snatches of chatter among women during visits to the clinic when Cindy was busy, or careless words from women who had been there longer and said too much. There were plenty of stories: about a girl who escaped but was found and sold to another boss. Or another woman who had an argument with Joe, then was contacted by her agent and told she would have to pay a fine and buy her own ticket home or be resold.

Eve often visited the room of a Thai woman who explained that she ended up at this job entirely by mistake. She had answered an online ad about a restaurant cook. But when she arrived in Tbilisi, her agent told her that the position had been filled and that the only way she could earn money to pay back her debt was to be a surrogate. The woman who recruited her warned her that if she tried to run away, the bosses would catch her and cut off her fingers. It had happened to her, said the agent, who held up her hand. Two of her fingers were gone.

A Local Industry in Chaos

Before 2022, most surrogates in Georgia were Georgian women. After decades of cynical politics and cronyism eroded the nation’s already low faith in institutions, the highest public trust was held by the Georgian Orthodox Church, which had strongly opposed I.V.F. and surrogacy, and combined with an already conservative culture led many surrogates to view their own situation as shameful. But Georgia is not a wealthy country — according to a 2024 survey, just over half of households reported struggling to buy food at least once within the past year — and the pay for working as a gestational carrier is attractive.

After Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, demand came from every corner of the world, and rates jumped to roughly $25,000 per pregnancy from about $15,000. Tbilisi’s 11 fertility clinics mushroomed to 24, practically overnight. In June 2023, Georgia’s prime minister suggested the country would ban commercial surrogacy, effectively cutting off the market to foreigners. Worry over an approaching ban led to an even greater demand to get in under the wire. Elene Gavashelishvili, a professor of anthropology at Tbilisi’s Ilia State University, told me that the Georgian government logged 1,172 surrogate births in 2023, a 43 percent increase from the preinvasion peak.

As Georgian surrogates demanded higher rates, clinics turned to foreign surrogates who could be paid significantly less, at rates that scale largely by race — women from Russia, Ukraine and Central Asia earn roughly $18,000 per singleton birth, Thai women around $16,000, while women from Africa make as little as $6,000. While there are no official statistics, multiple doctors in Tbilisi said that there are now more traveling surrogates than local ones.

This influx of business and surrogates brought chaos with it. When I arrived in Tbilisi in May, the industry was embroiled in scandal — Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty had broken a story about a surrogacy agency called Kinderly that simply stopped paying its gestational carriers, most of whom were traveling surrogates, after its two owners, a Ukrainian and an Armenian, each claimed that all the money was gone, stolen by the other. They had moved 17 of their stranded surrogates into a former hostel, but its owner turned off their electricity and hot water after the agency stopped paying the rent. They had been drying their clothes on the gas-oven doors and trying to boil meat dumplings in pots inside the ovens.

None had been paid for their work — they lacked even the money to get back to their home countries. Each had additional problems stemming from the industry’s poor treatment. Throughout her pregnancy, one Kazakh woman had read aloud to the fetuses she carried; she played music for them. But after the birth, she was not permitted to even see them. She found out their Chinese father had brought home another set of twins from a different surrogate months earlier, and she worried the girls she carried were not even being cared for by the man who ordered them. An Uzbek woman lost her uterus after her coordinator at Kinderly ignored her repeated attempts to inquire about her painful symptoms post-birth. By the time she finally came back to the hospital, the virulent infection was too dangerous to treat, and the doctors performed a hysterectomy on her while she was under anesthesia. (The risk of a hysterectomy is one reason it is generally recommended that a surrogate already have her own children.)

Another Kazakh surrogate had a falling out with her intended parents — they had sent her nasty messages and told her she could keep the baby, for all they cared. She was already five months pregnant, and from the moment we met, she offered, over and over again, to give me the baby.

In general, surrogates spoke about their own situations almost as if they were property. I sat with two Kenyan surrogates who explained their understanding of the system — that they would be “sold” from recruiter to agency to clinic. When I asked them how they would be OK with this, they said it was better than being abused as housemaids in Dubai. From a surrogate’s perspective of her rights in this process, once she arrives in Georgia, she can expect to undergo three embryo transfers before the agency will send her home. If a surrogate arrives and a clinic disqualifies her in the initial health check, or after one transfer, the agency might send her home, but more likely it would try to find a different clinic to accept her. This is foremost a business, and it costs the agency money to bring her over, house her and feed her, after all.

The official contracts she signs for the surrogacy, directly with the intended parents, tend to favor them over her. The language often includes additional compensation for twins ($2,000), for a hysterectomy ($2,000) and for a C-section ($1,000), as well as financial penalties for going into labor early ($3,000). But many clinics in Tbilisi routinely transfer multiple embryos, which increases the likelihood of early birth.

Given that the traveling surrogates would not speak Georgian, I wondered how they communicated with doctors to understand the procedures and risks. “She signs informed consent in the clinic,” Lika Chkonia, chairwoman of the Georgian Association of Reproductive Medicine and Embryology, said. “It has to be in the language which she understands, and the doctor has to explain all the details, what she is facing, what kind of complications she might have, what is the compensation for each complication.”

My reporting found something different — that many women working as surrogates were not being adequately informed. In fact, most of the 30 women I spoke with who had become or tried to become surrogates in Georgia had trouble communicating or advocating for themselves.

In a tidy Tbilisi apartment, surrogates from Central Asia shared rooms while working directly for one of Georgia’s biggest clinics. Not all the women spoke Russian, and with no interpreters they were forced to translate for one another. Their clinic coordinators often forgot their names, didn’t save their phone numbers and confused them with one another. An Uzbek woman started hemorrhaging late in her pregnancy, but surrogates told me the clinic ignored her calls. At the hospital, she put a friend on speaker to help translate as the duty nurse snapped: “You knew where you were coming! You are being paid for this!” As I was leaving their apartment, a coordinator called and threatened the women for what they had told me. One of the other surrogates in the apartment had reported on them. Days later, they said the clinic warned them it would withhold payment to any surrogate who spoke to me if anything negative about them were published.

Surrogates had their horror stories, while intended parents had theirs. There were important facts that agencies had failed to disclose to them — like that their surrogate was a teenager. Or the couple who showed up at the hospital to discover that their surrogate had no teeth. There were children born with birth defects that the intended parents believed were covered up by the clinics, or babies who died soon after birth. I heard stories about the wrong donor eggs being used, surrogates inducing early labor to speed up the process or even aborting embryo transfers so they could move from clinic to clinic, collecting payment for each transfer without going through with the pregnancy.

Clinics I spoke with claimed that recent scandals were the fault of outsiders coming to work in Georgia, but all the surrogate agencies were working with Georgian clinics and doctors. The Georgian Parliament was poised to regulate the industry in 2023, but the draft law mysteriously died. One theory for why is the political situation in Georgia itself: As with many things in Tbilisi, corruption seemed to have a role. When a human rights group brought a case against the Kinderly founders, it found obstruction at every level. “This is a multimillion-dollar business,” Baia Pataraia, the director of Georgia’s leading women’s NGO, Sapari, which represented the women, told me. “Somebody is making lots of money, and that’s why commercial surrogacy with very few regulations and nonexistent monitoring remains. If they wanted to regulate it, they could.”

‘What’s Happening? Is There Anything Wrong?’

Among the women of House 3, the stress of waiting was getting to everyone. After weeks of being cooped up together in close quarters, living with the unpredictability of doctors’ pronouncements and their own bodies, the house could verge on savage. One time a woman brandished a knife at another, accusing her of leaving scraps of food on the floor, screaming she would stab her.

In mid-December, Eve got in trouble for gossiping with some newly arrived women. They were making a fuss about giving in their passports; Eve told them to just do it. She explained that women from another house said Joe and Cindy weren’t bringing them their fertility medication on time, maybe to punish them for breaking the rules. Eve was just trying to warn them to stay in line, but Joe thought she was slandering him. Eve didn’t know who said what — but the newly arrived women must have told someone. Maybe the interpersonal fights everyone was having all the time had been weaponized against her. “I think there might be a misunderstanding,” Eve replied to Joe when he messaged her directly. “I am not spreading any bad information.” She was panicking; she needed this money. She couldn’t risk being sold to a worse house or being sent home.

Soon after, everything started to fall apart. Right before Christmas, Eve was told she would get some kind of procedure — Cindy told her something electrical, some kind of stimulation, or at least that was what she understood. They arrived at the clinic in the morning, and Eve waited for hours. It was nearly the afternoon when they finally came for her. She had been fasting all day. She was told to remove all her clothes and her shoes, and change into the clinic-provided socks and a blue hospital gown, so thin that Eve worried you could see everything through it.

Eve was taken to an operating room. Inside, there were two exam tables — slightly inclined chairs with stirrups. A nurse began to yell at Eve in Georgian, gesturing to her to get up. Other nurses were rolling out machines. One had a tube coming out of it. When they turned the machine on, it made a deep whirring noise. The nurses were talking to one another loudly. One of them tied Eve’s thighs down with black straps. They looked at Eve’s genitals and laughed.

The doctor came into the room. Eve could not see much from her vantage point, just the top of her doctor’s head, but she could feel them insert an ultrasound wand into her vagina, and then they started yanking it, hard. She winced. Then they inserted the tube. Whatever the machine was doing added a whole new level of pain she had never experienced — a really sharp burst of pain — but then it stopped. Then another. Eve didn’t know how long it lasted, only that she kept telling herself to endure it. How could she even describe it? A sharp punch and a vibration? A sucking sensation?

She clamped her mouth shut and stared at the ceiling — she didn’t know where else to look or to turn. She would remember the color, its whiteness. After they finished, they removed the machine and crossed her legs, one over the other, and left her lying there.

“What’s happening?” she tried to ask, in broken English, but the doctor ignored her. “Is there anything wrong?”

Maybe these doctors didn’t speak English, she thought. She tried Google Translate, but no one paid her any mind. She kept asking.

“No,” they said dismissively. Eve walked out of the room.

Afterward, she bled. It hurt to lie down; it hurt to pee. Back at AIA, she asked everyone what they thought happened to her. Had anyone else experienced anything like this? Everyone said no, and the house grew more scared: What had they done to her?

Eve’s concern for herself was quickly overtaken. That week, Eye started bleeding profusely. Her stomach hurt; she doubled over in pain. She couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat, couldn’t understand what was happening to her. Cindy told her to continue taking her fertility medication. But when Eye started bleeding in clumps, Joe took her to the hospital. She was crying so hard that she felt like she couldn’t breathe, her ribs hurt so much. The doctors put four needles in her. Her mind stopped working, and she fell unconscious.

The next day, Eye woke up and found Star, another woman from the house, in the room with her. Star had been brought to the hospital with the same symptoms. A 33-year-old mother of two, she had finished college with a degree in public administration in Thailand, but it had been hard to find a job. She had a lot of problems with her husband and in-laws, and after a particularly heinous fight about money, she too answered a Facebook post. Neither woman could stomach the hospital food — oatmeal and black tea, some kind of yogurt or sour and salty soup. They messaged Eve that they had to drink water from the bathroom tap. When they showed their bloody sanitary pads to the doctor, they were told it was fine and to throw the pad in the toxic bin. Both women were so afraid, alone in a foreign country, with no idea what was happening to them. They were hospitalized for a week.

No one would know if it dawned on everyone all at once or more slowly, but after Eye and Star came back to the House, everyone started talking about trying to run away. It unfurled quietly in the rooms, tendrils of whispers between roommates. Eve and Eye discussed it in hushed tones between themselves: It had been months without a transfer. How much longer can we really be expected to wait here? Sometimes, Eve thought about just jumping out of their window. She wasn’t sure if the fall would be high enough, but then she thought at least if she died, these kinds of things would stop happening to her. Then Eve thought of her father — who would take care of him if something happened to her? — and decided she had to survive. She had to find a way to get out.

An Immense Chinese Market

At the end of January, Cindy sent Eye a message asking for her age, weight, height and educational level, as well as for a photograph of herself as a child and another without makeup. “Someone wants a Thai donor,” Cindy explained. “So I recommend you.” The rumors they heard about women being pressured to sell their eggs were true.

A few days later, Cindy and her mother took Eye to the store to buy skin-whitening cream. Eye was pretty but too dark, they said: Chinese people prefer paler complexions. They told her to slather it on.

Not long after, Eye was introduced to a Chinese couple, a man and a woman, who came to see her at the AIA hotel. Eye didn’t know what to make of them. She imagined they would want to vet her carefully, but they just glanced at her and left. She didn’t think they looked pitiful. They looked young. Eye was taller than either of them, and her skin was much darker. They should be looking for people more similar to them, Eye thought.

For the global fertility industry, China is an immense market. The country’s population is 1.4 billion; assuming that the normal range of 10 to 20 percent of adults face infertility, that means 67 million to 133 million people who might make use of assisted reproductive technologies. Demand is further driven by the effects of the disastrous one-child policy, which caused its own demographic crisis. In 2015, when the policy was changed to allow all couples to have two children, more than half the women who would become eligible to have a second child were older than 35, according to China’s national health agency. This created a surge of would-be parents in their late 30s to early 40s, a time when egg quality declines precipitously. Demand also comes from couples who have lost their first child, single people and a growing number of L.G.B.T.Q. couples. (Three children were allowed in 2021, a shift that has created even more demand.)

And yet despite the extremely high levels of Chinese demand for ART, pursuing treatment inside the country is difficult. Gay couples are generally refused official recognition as parents, while heterosexual couples seeking treatment at government clinics find them tightly regulated, with lengthy wait times. Few Chinese women donate their eggs, yet sales of sperm and eggs are banned, as are various kinds of embryo testing, including sex selection; surrogacy, too, is prohibited. For this reason, many Chinese intended parents who can afford it end up traveling abroad for services. (There is also a large gray market for ART in China.) Last year, according to Nino Tarkhnishvili of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Chinese intended parents overtook Israelis as the largest group of foreigners in Georgia for surrogacy.

Across the world, East Asian eggs are extremely lucrative — an attractive woman with an Ivy League education can earn as much as $250,000 per cycle in the United States. Women from Taiwan, who don’t need visas for travel to America, often fly in to donate eggs for tens of thousands of dollars.

Eye was not sure how to respond to Cindy. She knew that she didn’t want to sell her eggs, but she also knew she couldn’t just say no. When Cindy messaged her again, to say they would wait until her next period to go to the doctor to see how many follicles she had, Eye promised herself it wouldn’t happen. She promised herself she would figure out a way to escape.

A week later, Star was taken to the hospital in the city for what she thought would be a routine appointment. She didn’t understand why she wasn’t taken home a few hours later. It was 9 p.m. when they brought her to the operating room. She got in the stirrups, then she got an injection. She saw an IV drip, and then she passed out. When she woke up, someone was hitting her to get up. Her feet were still in the stirrups. She didn’t know how long she had been unconscious. She didn’t know what happened. They took her to the bathroom. She saw a lot of blood. She was overcome by a deep, numb terror.

For weeks afterward, Star would be lightly bleeding. Later tests would show she had a buildup of fluid in her abdomen, which strongly suggested she had ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), a known risk of egg retrieval whose symptoms can include nausea and bloating, ovary torsion, fluid accumulation in the lungs and abdomen and kidney failure. Fertility clinics generally tell women that severe OHSS afflicts 1 percent of those who undergo the procedure, but a 2023 study of donors by Diane Tober, a professor at the University of Alabama, found a much higher rate: 12 to 13 percent. Doctors would say it was impossible to know exactly what procedure was performed on Star, especially without her medical record from before the mystery surgery. She could have had any number of womb-preparing procedures, like the removal of a fibroid or polyp. But the women’s own hypothesis was that Star’s eggs had been retrieved without her consent.

People who worked in Georgia had no trouble believing this theory. An agent who worked in Tbilisi until recently, and who requested anonymity because of her ongoing involvement in the industry worldwide, told me she was “99.9 percent” certain that some women in Georgia were having eggs retrieved without their consent. Egg theft happens all over the world — whether it’s unauthorized retrievals or misuse of the eggs retrieved with consent. Earlier this year, Greek authorities announced that a clinic had engaged in at least 75 cases of gametes being stolen from one client and diverted to another. In 2017, the same thing happened in India. In 2016, an Italian doctor was arrested after a woman accused him of tricking her into an egg retrieval by telling her he was removing a cyst. In 2009, there was egg theft in Romania. In the late 1990s, a doctor in Israel repeatedly stole eggs from his patients, in one instance transferring 181 eggs from one patient into the wombs of 34 others.

Eve and Star’s procedures were not anomalies. Most women I spoke to were uninformed or ill informed about what was being done to them. Many of them had no idea how many embryos had been transferred into their wombs. (Clinics are legally obligated to explain every procedure.) Even those who were told what procedures they were having weren’t always convinced they were being told the whole truth. They weren’t told details of the medication they were prescribed. They only allowed them to take photos of their prescriptions, but the papers themselves were taken back. When they tried to speak to the doctors, they were dismissed.

‘Should We Go Now?’

Everything changed with one news conference. It was posted online and quickly went viral, passed around by text message through closed doors. Eve, Eye and Star, who had moved into a larger room together, all saw the clips. It was put on by the Paveena Foundation for Children and Women, a Thai NGO led by an ex-minister named Paveena Hongsakul, and it claimed that hundreds of Thai women were being held in Georgia against their will and forced to produce eggs for a Chinese gang.

The allegations were written and rewritten all over Thai and international media. The featured speaker was a Thai woman who went by Na, who explained that upon her group’s arrival at the AIA hotel in Georgia, she was taken to another house for lunch, where she overheard that women who wanted to go home were being forced to sell their eggs to earn their passage. When Na refused to give the bosses her passport, a fight ensued. She threatened to jump out of the building and kill herself rather than hand over her documents. She demanded to leave. One boss told her she would have to pay 70,000 baht as a penalty. Na called her family, who raised the funds to cover the ransom and bought her a ticket home, and Na left Georgia four days after she came. Her roommates pleaded for her not to forget them there, so once she returned to Thailand, Na contacted the Paveena Foundation, which in turn contacted the Thai authorities, who contacted the Georgian authorities, who tracked down Na’s roommates. The foundation then paid for them to return to Thailand.

“Nobody became gestational carriers,” Na said at the news conference, repeating the rumors she’d heard. “They were forced to sell their eggs.”

“We want to warn Thai women about this,” Paveena declared. “We want to make an announcement to the Chinese and Thai government: How can this happen? How can this happen in our world?”

A BBC investigation identified the man who threatened Na as Joe, and the company as BabyCome. Until then, Eve hadn’t even heard that name before — the name on the “contract” she signed with Joe and Cindy when she first passed her health check was something entirely different. The whole house took notice: All the rumors, threats and “precautions” finally made sense. That night, Bee, who had arrived recently from Thailand, came to speak to each of the women and gave everyone back their passports. “Do any of you want to go home?” she asked them individually. “If you want to go home, you have to pay 70,000 baht.”

“Who can find that money?” the women remarked to one another. “If I was able to find the money, we could have just bought a ticket and gone home before.”

One morning soon after, the house woke up to find that two women had vanished. The hallways were rife with speculation. A woman nicknamed Fat May told everyone that she heard something bumping on the stairs at 1 or 2 a.m. She assumed someone was headed to the kitchen for a late-night snack. Because the women mostly kept to themselves in their rooms, the news spread both quickly and slowly. Eye heard as soon as she emerged in the afternoon to make breakfast. She came back to her room and sent one of the missing women, Pim, a message: “Where are you?”

Two days later, Pim replied. She was back in Thailand: Some people from home had sent her and her roommate, Toey, money for their tickets. “If you really want to go home,” she said, “I can find someone to buy the ticket for you.”

Neither Eve, Eye nor Star hesitated. Pim connected the three with a group called the Immanuel Foundation, a Christian organization that works with survivors of human trafficking. Pim explained that they would have to leave as soon as the foundation had booked their flights — and that could be at any moment. Eve began selling her things: She knocked door to door, saying she needed money quickly for her father, selling the items she’d carefully rationed all these months at a quarter of their value — dried chile, dark chocolate, moisturizer and baby oil, packets of MSG seasoning powder. She ended up with roughly $13. Better than nothing, she thought.

When their flights were purchased, Eve booked a hotel online, far from AIA, and they began casing the house to plot their escape. They decided they would run the night before their flight, so they had three days to plan. But later that same day, they noticed Cindy cleaning a room on the third floor, carrying a mattress and what looked to be the family’s personal belongings into the room. If she and Joe were moving upstairs, the three women realized, it would make it much harder for them to escape. They resolved to leave that night.

In the early evening, the three women dawdled in the kitchen, marinating pork to grill, trying to act nonchalant. They waited until everyone else was done with dinner and had returned to their rooms. Eve and Star went up to the fourth floor to gather everything.

Eve messaged Eye that they were ready upstairs.

“Come now!” Eye texted Eve.

“No, wait!” she texted again. Another woman was coming down the stairs.

“I will wrap clothes over the luggage pretending to do the laundry,” Eve texted.

Eve went down with the first bag, holding it above her head wrapped in towels — a ridiculous spectacle, but she didn’t have any other ideas. Despite the three flights of stairs, she made it back to their room undetected.

All three women took a minute to steady their nerves. On Eve’s second trip down, she heard a noise. Is that a door opening? Eve stopped breathing. She moved faster. Everything went quiet again.

After their bags were hidden, the three women stayed downstairs. At 9 p.m., they saw Cindy’s father drive out. “Should we go now?” they asked. As they debated, they saw headlights pulling into the driveway. It was Joe and Cindy’s car. But then the headlights turned on again, and the car pulled out. “They probably forgot something,” the women agreed. They could be back at any moment.

Without thinking about it, Eye tried the same door Star had tried earlier that day. It was open. Cindy’s father must have forgotten to lock it. Eye couldn’t believe their luck. This was their last chance. “Just get out!” Eve called to her friends as she picked up her luggage and tore out of the house. The other two women followed her, dragging their own bags, bumping, stumbling down the hill in the darkness. Car lights flashed behind them, illuminating the cobblestone street. It’s them, it’s their car! They’re back! They’re after us! Run! Run! Run!

The women ran harder, turned the corner, ran more, ran farther, until they were enveloped by darkness. A thin snow had begun to fall.

Retracing Their Stories

The following week, I met five of the women — Eve, Eye, Star, Pim and Toey — in the Immanuel Foundation’s safe house in a picturesque, gated compound complete with a security guard and a children’s playground on the outskirts of Bangkok. They were providing testimony to the Thai authorities, spending hours at the Ministry of Justice’s Department of Special Investigations. Jaruwat Jinmonca, the Immanuel Foundation’s vice president, shuttled them to the headquarters the day after they landed. He had pushed to start a criminal case against BabyCome, though he realized it would be unlikely to yield much of a result.

Altogether, I interviewed eight women who had escaped — one group assisted by the Immanuel Foundation and another group assisted by the Paveena Foundation. We sat for days, hours on end, retracing their stories, their movements, looking at their chat records, at photographs they’d taken, screenshots of WeChats they made before deleting their accounts as they prepared to cross back into Thailand. The women were patient, and they didn’t mind my questions; they wanted to tell their stories, hoping it might change something for a surrogate somewhere else.

It’s not unusual for survivors of trafficking to be trafficked again. I asked Eve and Eye whether they would compare their experience in Georgia with the one they had in Bahrain, where promises of massage work led to forced prostitution.

They immediately declared that Georgia was worse than Bahrain: It was so isolating, as they didn’t know who was their friend and who was secretly reporting on them to Joe or to Bee. In Bahrain, the women helped one another; in Bahrain, they actually got paid, because despite their “debts” to the traffickers, they were receiving cash tips. But worse, in Georgia they really had no idea what had been done to their bodies. Sex work was self-explanatory, but white pills, injections and suppositories could be anything.

“In Bahrain, we know our bodies — whatever we are doing, we know our health,” Eve said. But her time in Tbilisi was different. “It’s almost like I’m not the owner of my body. It’s like I brought myself to be tortured over there.”

I asked them for permission to ask their doctors and Joe or Cindy about what really happened to them, with their real names. The women were scared of retribution, worried that Joe and Cindy or their network would come after them, unmask them on Facebook to their communities and families, damage their reputation and threaten them. Despite sharing those fears, Eve said yes.

In Tbilisi, I asked to meet the founder of LeaderMed, Nato Khonelidze, but she declined, instead sending her clinical director, a tall, thin neurologist named Davit Barabadze. I asked Barabadze about the claims the women had leveled against the clinic: language barriers, lack of informed consent protocols, the use of surrogates who did not have their own children, unexplained and terrifying medical procedures. With Eve’s permission, I cited her story with her full name, explaining that she told me she had been strapped to a table and a procedure was performed on her that she did not understand. For nearly an hour, Barabadze cited confidentiality laws to deflect specifics. (Later, in response to fact-checking queries for this article, LeaderMed responded: “We reviewed the audits of complaints and claims handled by our clinic during this period, which are conducted on an ongoing basis, and no such or similar incident has ever been recorded.”)

LeaderMed’s official position was that it always provides documents to surrogates in a “language they understand,” but Barabadze confirmed that there was no Thai-language documentation in the clinic. I asked how the clinic verified whether women actually understood the documents they were presented with. “No one verifies it,” he replied.

At LeaderMed, I also met Cindy. Joe had specifically instructed me to “go to our office” and gave me a room number at the clinic. Joe sent her in his place, after repeatedly canceling our scheduled meetings — first saying he could meet, but then claiming that he was stuck in China, then saying Cindy would meet, but then she wouldn’t, then she would.

Even though the entity was legally registered in her name — her Chinese name is Li Juan, while Joe’s is Tan Zhuo — Cindy claimed not to know how many employees the company had, or how many surrogates. She did not know who found or brought intended parents from China. She said that the company had assisted in the births of dozens of babies, but when I asked for a more specific number, she replied, “I’m not certain.”

I asked Cindy about how she could expect women to wait for months without any payment. “If she hasn’t actually done the job — she has food, a place to stay, and clothes — but then you want me to give her money too? That would be too expensive.” She explained that if they paid them even a small monthly salary, they feared the women would just run away. As for the question of informed consent, she said: “Whenever they come to the hospital, the doctors will give them things that they can read or look up themselves.”

I asked Cindy why so many women would return to Thailand — 17 that I knew of — many of them telling the same story: that they didn’t know what happened to them, that they were too cowed to confront the system that kept them in Georgia, too vulnerable in these kinds of power dynamics to stand up for themselves. She said she didn’t know, but they were probably trying to extort them.

When I brought up Eve’s case specifically, Cindy seemed surprised I had spoken to her; her mysterious procedure, she claimed, was the removal of a cyst with “some kind of electrical stimulation.” After I left, Joe messaged me and said Eve was a liar and a troublemaker, whom he had been planning to send home anyway. When he was contacted before this story went to press, he replied through a translator: “People who slander others without any bottom line will eventually go to hell.”

‘A Different Kind of Exploitation’

There is a callousness to the way our society discusses the decision to have children — as if whim alone were enough to conjure a child. An infertility diagnosis can be devastating, rendering the pathway to parenthood difficult, riddled with unexpected complications and pain. For those who want children but can’t have them, the fertility industry offers the possibility of a remedy, and to surrogates and egg donors it offers the promise of a better life. But the market it creates is one in which everyone meets at their most vulnerable, preyed upon by forces and emotions so much larger than them, often in countries with little legal protection for either party if something goes wrong.

Perhaps it was inevitable that at the collision of social pressure and biological demand, there would be a monetary value on the most vulnerable products — babies. It is a universal human right to be allowed to have a family, but that is not the same as the right to a child. The whole industry forces us to ask uncomfortable questions: What is the value of a mother? What is the value of a baby? How can a transnational industry in this world of glaring inequality be entrusted to set that price?

“We talk about surrogacy’s exploitation in terms of surrogates and babies, but we don’t talk about intended parents, who are sold a lie,” Sarah Jefford, an international-surrogacy lawyer in Australia, told me. “They come in wanting to make sure the surrogate is well cared for. Agencies say all the right things, and they believe them, no reason to not. Until they realize later that they’ve missed a few things: whether there was an interpreter, whether they could have direct contact with their surrogate or whether she had access to a lawyer. The agency has a very nice website, and they spoke to intended parents who said they had a good experience. They’ve just handed over their life’s savings. It’s a different kind of exploitation, but it’s part of it.”

In Georgia, plenty of agencies had swindled intended parents with promises of a seamless process, only for the parents to realize later that the paperwork the clinics and agencies submitted was incorrect. One American mother I met had been in Tbilisi for over a year waiting for her baby’s birth certificate. The woman, Alyssa, had one child through a successful surrogacy journey in Texas, but even so, and despite the due diligence she thought she had done, she found herself working with an agency that defrauded her and her Georgian surrogate. In her experience, too many parents coming to Tbilisi were blinded by their own desires, unwilling to admit that the market had rendered them complicit in its cruelties — that in their yearning for family, they had become exploiters themselves.

“I have told anyone who will listen in these Facebook groups on Georgia surrogacy, and no one cares,” Alyssa told me. “They were only concerned with their ability to have a child.”

Ethical guidelines for commercial surrogacy exist to ensure the health, autonomy and rights of all parties involved — thorough psychological evaluation and counseling; health screening; informed consent, including about the additional risks inherent to surrogacy; fair compensation independent of the outcome; separate legal representation for intended parents and surrogates; health insurance and care for the surrogate after the birth; lost-wage compensation; child care for her children; travel stipends; maternity clothing allowances; and escrow accounts for payments.

Many advocacy groups discourage going to developing markets, where it can be more difficult to know whether a surrogate is consenting and can create legal problems for the child. Traveling surrogates further complicate this scenario. Any situation in which a surrogate is removed from her home country and has no genuine opportunity to exit the process would be human trafficking under the United Nations definition of the term. But ethical surrogacy is expensive, and such inexhaustible demand means that markets flourish wherever they can — Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, Kyrgyzstan and Kenya. Industry observers even have a name for the pattern: Whac-a-Mole surrogacy. The industry profits so far exceed the payment of donors and surrogates that greed begets more and more exploitation.

Then there is the question of how this affects the children. Research suggests the ideal for donor-conceived and surrogacy-born people is openness: Tell children early and often, normalize it and let them meet donors and surrogates if they want to. Reproductive tourism complicates that. Women can be impossible to find again, along with their updated medical histories, records and any genetic half-siblings.

A whole generation has been born of this international assemblage. A Chinese father I met in Tbilisi showed me a photo of his son’s Georgian egg donor with striking sapphire-colored eyes of almost impossible proportions. Next, he showed me a photo of his son. Their eyes were identical — the shape, the color. It was haunting. Would this child not be curious about the history of these eyes and whether anyone else out there shared them too?

The Most Dehumanizing Side of the Industry

It is undoubtable that many intended parents who came to Georgia had perfectly reasonable experiences from their perspectives and were able to create the families they dreamed of — perhaps their surrogates were happier than any of the ones I interviewed. But what about the dangers inherent in the system they benefited from and what it did to the women who worked in it? Despite the Immanuel Foundation’s attempts, the Thai women would have relatively little assistance to process what they had lived through. (A representative from Thailand’s Department of Special Investigations said they were continuing to investigate BabyCome and its network, believing the women to be victims of human trafficking. In Georgia, meanwhile, authorities reversed their initial decision to recognize the Kinderly surrogates as trafficking victims; instead, prosecutors charged the founders with embezzlement.)

Within a week of getting home, Eye told her mother what happened in Georgia, but Eve vowed never to tell her father. She didn’t want to risk disappointing him.

A few days into knowing Star, I asked, with the assistance of an interpreter, what she thought happened to her. “They put me under anesthesia,” Star replied, “and they were operating, so I don’t know whether my eggs got harvested or not. They didn’t tell me what’s wrong or what is happening.”

“What do you think happened?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” she said, trailing off. “I cannot think.”

I asked if she meant she couldn’t think of an answer to my question, but my translator replied the answer was just that she couldn’t think at all. What Star repeated, a few times, was just how terrified she was, waking up in the stirrups. “Then there was blood,” she said, and trailed off again. Eye and Eve said Star had been like this since the operation — slower to think, slower to react, sometimes unable to think at all — she was a diminished version of herself. Star explained that she planned to go stay with her parents for a few months; she was not prepared to go home to see her children or her husband.

It was impossible to know what really happened to any of the Thai women in the clinic. Several doctors said that Star’s test results fit most closely with an egg retrieval, though they could not be sure. But the other women, even those whose procedures did not sound like retrievals, had come to believe their eggs were taken, too. All these women had experienced the most dehumanizing side of the global fertility industry, and after what they endured — the lack of explanation from their doctors or Cindy, the rumors circulating among the houses, the intimidation and the threats of punishment, the confiscation of their passports, the withholding of promised payments and the mysterious operations — who could blame them for believing that even more nefarious things had been done to them? Suspicions floating around the houses had been repeated on television by figures of authority, then solidified and rearranged themselves into logical conclusions. Given the lack of transparency, they grasped at the clearest narrative available.

The Thai women’s lack of clear consent was particularly disturbing; it felt like a most basic covenant of medicine had been broken by the medical professionals themselves. The doctors who ignored the women’s attempts to speak with them, who did nothing to ensure they could repeat back what would be happening to them, who saw them only for their wombs.

We all sat together at a dining table in the tidy house. Often they had interrupted one another with enthusiasm to share their opinions, but now they were quiet, perched on their chairs, listening to their reflections on what they had endured. I asked Eve what she thought of surrogacy after everything. She had believed it to be a kindness on top of a paycheck when this began. “They don’t see us as human,” Eve told me. “They don’t think about whether the medication will damage our bodies or not. They just put everything into our body without thinking about our health for the baby to survive.” The other women nodded, silently.

The post ‘They Don’t See Us as Human’: The Dark Side of the Global Fertility Industry appeared first on New York Times.