Pvt. Fitz Lee’s life descended into misfortune and misery after he helped rescue fellow American soldiers in Cuba in the late 1800s.

Sickened by complications of malaria from his deployment, he was presented with the Medal of Honor in a military hospital in Texas and was soon after medically discharged from the Army in the summer of 1899.

He died 10 weeks later, blind, homeless and with no known next of kin. He was 33.

For more than a century, he was remembered by nearly no one. Private Lee, this Black U.S. Army veteran, was buried beneath a magnolia tree at the military cemetery at Fort Leavenworth in northeast Kansas.

Then this year, someone at the Pentagon found a use for him.

For decades, an Army base in Virginia was named for Robert E. Lee, the defeated Civil War general who had owned slaves. In 2021, a new law mandated the removal of Confederate names from military assets. The base was renamed Fort Gregg-Adams to honor two pioneering Black Army officers who had overcome segregation in the military.

But after returning to office, the Trump administration was determined to rewind history. A law prevented the restoration of Confederate names, so it did it in a most unusual way. The base is now called Fort Lee again and named — officially, anyway — for Fitz Lee.

But who was Private Lee?

Gaps in His Story

The little that we know about him comes entirely from his military service records.

They say that he was born in June 1866 in Dinwiddie County, Va., and that he enlisted in the Army’s 10th Cavalry Regiment in Philadelphia on Dec. 26, 1889.

He is described as a “laborer,” single and childless. At the time he was 23. But the records say nothing about his parents or upbringing in the era immediately after slavery was abolished.

He was born a little over a year after one of the last significant battles of the Civil War, known as the Battle of Dinwiddie Courthouse. Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, a nephew of General Lee, commanded a cavalry unit there.

But with no birth records and no descendants, it is impossible to know what, if anything, connects Fitz Lee, a Black man born in a former slave state, to the white Lees of Virginia.

Private Lee’s records do not explain what took him to Philadelphia, 250 miles north of his birthplace. But he then spent his entire military career with the 10th Cavalry, an all-Black regiment led by white officers that Congress had established in 1866. Its members were nicknamed Buffalo Soldiers.

His assignment took him West. He re-enlisted twice, in 1894 and 1897, at Fort Assiniboine in Montana.

It was a time when Buffalo Soldiers escorted stage coaches, patrolled the frontier and policed Native Americans, said Jason Fung, an archivist at the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum in Houston.

Mr. Fung said that people who followed Buffalo Soldier history had been surprised by the choice of Private Lee. “Not much is known outside his Medal of Honor story,” he added.

A medical record offers this glimpse of his frontier experience: He was kicked by a horse “in the line of duty” in April 1890, suffered a slight contusion below his left knee and spent three days recovering. He fell from a horse in February 1894 and sprained his left ankle, also in the line of duty, forcing 10 days’ furlough. He had two recorded bouts of “acute bronchitis” and a thigh muscle pull from “unloading ice in line of duty” during that period.

He sailed aboard a steamship that left Florida for Cuba to fight in the Spanish-American War on June 21, 1898. Nine days later, U.S. and Cuban revolutionary fighters landed and lost a skirmish with the Spanish forces. After others had failed three times, Private Lee and three other Buffalo Soldiers “voluntarily went ashore in the face of the enemy” and rescued the wounded, an act of bravery for which all four were awarded the Medal of Honor.

The war ended in December 1898. Private Lee was already sick. On Sept. 22, 1898, he had been diagnosed with “malarial fever intermittent,” according to a War Department document.

It progressed to kidney disease, “chronic parenchymatous nephritis” that disabled and blinded him. He was hospitalized for more than three months starting in March 1899 at Fort Bliss in Texas, where he was presented with the medal.

He was discharged on July 5.

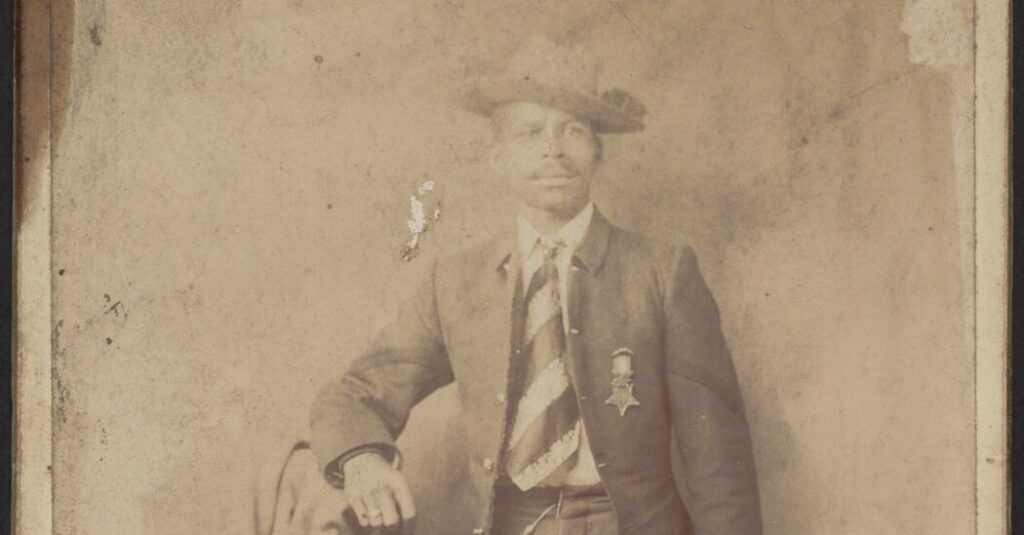

Just one photo of Private Lee is known to exist. It is in the Smithsonian’s collection and must have been taken during his last three months of life. He has the Medal of Honor on his blazer.

Oops. Fitz, Not Robert E.

President Trump made no mention of Private Lee on June 10 when he announced at a pep-rally-style appearance at Fort Bragg, N.C., that the Pentagon would revive Confederate-era names.

“A little breaking news: We are also going to be restoring the names to Fort Pickett, Fort Hood, Fort Gordon, Fort Rucker, Fort Polk, Fort A.P. Hill and Fort Robert E. Lee,” he said. “We won a lot of battles out of those forts. It’s no time to change.”

The president was wrong — there would be no “Robert E.” in the name. And he failed to mention that, because the law forbade changing the names back, the Pentagon had developed a workaround.

It had Army personnel and historians search old service records for veterans with the same last names, Cynthia O. Smith, an Army spokeswoman, said in a statement. They then narrowed the list to heroes who had been awarded the Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross and Silver Star. One of those was chosen after a final search “to ensure the candidates had nothing derogatory or objectionable in their service records or conduct.”

It is not known if Army historians tried to shed light on the first 23 years of Private Lee’s life or knew of his struggles, or why he was chosen over other Lees who had received medals.

The Army statement said Fitz Lee had been singled out because his “service was obviously worthy of veneration and emulation, and whose personal service story was moving and compelling.”

Ejected Esteemed Black Officers

His selection also let the Army undo the work of a congressionally mandated commission that was created during the Biden administration to remove Confederate names from U.S. military installations.

Fort Lee’s name was changed on April 27, 2023, ending a century-long tradition. That day, Fort Gregg-Adams became the first U.S. Army base to be named for Black Americans.

Historical material explained that both honorees, Lt. Gen. Arthur J. Gregg and Lt. Col. Charity Adams Earley, had commanded logistics and support units, which had long been primarily staffed by Black troops. Both were commissioned in the era of segregation and served with distinction.

General Gregg, the first Black man to reach the rank of an Army three-star general, was there, as were the son and daughter of Colonel Adams, the highest-ranking Black female Army officer in World War II. She died in 2002.

General Gregg, 94, retired in 1981 after a 35-year career, mostly in the Quartermaster Corps, and became the first living person in modern history to have an Army installation bear his name. As a young officer, he served at Fort Lee during a period when the officers’ Lee Club had a whites-only policy. It was renamed the Gregg-Adams Club.

Lt. Col. Charity Adams Earley commanded the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, the first large unit of Black servicewomen to be deployed overseas — in this case, 855 soldiers who went to Europe in 1945 for World War II.

The unit devised a system to sort and deliver millions of pieces of mail from families to American troops who were on the move across Europe.

In the turmoil of war, the U.S. military’s leadership had allowed parcels and letters to pile up in rat-infested warehouses in Birmingham, England. Colonel Adams’s unit worked around the clock, processing nearly six million pieces of mail each month and providing a morale boost to men in the theater of war.

The unit received little recognition until 2018, when some veterans put up a black granite monument with a bust of Colonel Adams at Fort Leavenworth, which had been an early training ground for Buffalo Soldiers and continues to honor the legacy of Black Army service. It is also the final resting place of Fitz Lee and other soldiers from the Spanish-American War.

Six years later, the Tyler Perry movie “The Six Triple Eight” came out with Kerry Washington playing Colonel Adams.

General Gregg died on Aug. 22, 2024. Before his burial at Arlington Cemetery, a cortege carried his coffin to Fort Gregg-Adams. Thousands of soldiers lined the roadways and saluted his last ride through his namesake garrison.

General Gregg and Colonel Adams are familiar names among students of Black military history. Private Lee is not.

“Never heard of this guy,” said Joana Scholtz, the N.A.A.C.P. president in Leavenworth, Kan., who is an Army veteran and is married to an Army veteran. “Never been to the grave. Nobody has ever even mentioned his name. And I’m pretty immersed in Black culture and Black history.”

A group of retired military members who gathered at Fort Leavenworth on Buffalo Soldiers Day this year were mostly perplexed about Private Lee’s role in the renaming of Fort Lee in faraway Virginia. But not Ms. Scholtz.

“It’s their way of basically whitewashing the renaming of that fort,” she said. “So people will say once again ‘Fort Lee, Fort Lee, Fort Lee.’ But nobody will think about Fitz Lee because nobody knows who he is.”

Final Days

What we know about Private Lee’s last three months of life comes from documents found in his pension file created by the War Department in 1899.

He had reached Leavenworth, Kan., five days after he was honorably discharged 950 miles to the south, in El Paso. White people lived in one part of Leavenworth and Black people in another, including a community of retired Buffalo Soldiers. Its first hospital for “afflicted colored people” would open two years later, in 1901.

Private Lee filled out an application on July 10, 1899, for an invalid’s pension with the help of Harry Planter, a Black attorney. It says Private Lee paid him 50 cents for postage and expenses.

How he spent the next month is a mystery. But on the night of Aug. 22, 1899, he showed up at 127 Cheyenne Street, the home of a fellow former 10th cavalryman, Charles Taylor, 27, and his wife, Cora.

Private Lee was “sick, totally helpless, totally blind” and suffered from a swollen face, feet, legs and stomach, according to an affidavit dated Sept. 11, 1899, that was signed by Mr. Taylor and Charles Giles, another former 10th cavalryman.

The private was a pauper, it said. He had “no money, no means of support of any kind and is wholly depending on charity.”

The Taylors gave him “a bed and room and nursed him,” and they paid a prominent Black doctor, C.M. Moates, to attend to him. Mr. Giles paid for his medicine, it said.

His situation was so dire, the veterans said, that he “will not survive very long.” He lasted three more days.

Private Lee’s death was reported in a two-paragraph article under the headline “A Black Hero,” on Page 3 of the Sept. 15, 1899, edition of The Evening Standard, a local newspaper.

This was the sub-headline: “Wearing a Medal of Honor for Great Gallantry in Cuba, He Dies Penniless Yesterday Afternoon.”

The article said “he died without means and through the efforts of ex-soldiers at Leavenworth was given a soldier’s burial at the national cemetery this afternoon at 2 o’clock.”

On Oct. 4 of that year, The Leavenworth Times reported that the Leavenworth County Commission had agreed to reimburse the undertaker for his funeral expenses. The sum was $21.

Private Lee never received the pension; he passed away before his application could be reviewed. Scrawled on two old envelopes in his file is the word “Dead.”

Epilogue

At Fort Lee today, the military has identified an empty wall at the headquarters for a portrait of Private Lee. The decision to rename the base was done so hastily that the Army did not have time to prepare one.

Portraits of General Gregg and Colonel Adams remain.

Carol Rosenberg reports on the wartime prison and court at Guantánamo Bay. She has been covering the topic since the first detainees were brought to the U.S. base in 2002.

The post The Mysterious Life and Afterlife of Private Fitz Lee appeared first on New York Times.