Your Mileage May Vary is an advice column offering you a unique framework for thinking through your moral dilemmas. It’s based on value pluralism — the idea that each of us has multiple values that are equally valid but that often conflict with each other. To submit a question, fill out this anonymous form. Here’s this week’s question from a reader, condensed and edited for clarity:

I’ve worked in communications for the past decade helping get important ideas out to the public. I’m good at what I do and I think it’s useful, but I don’t really feel like I’m having a grand impact on the world.

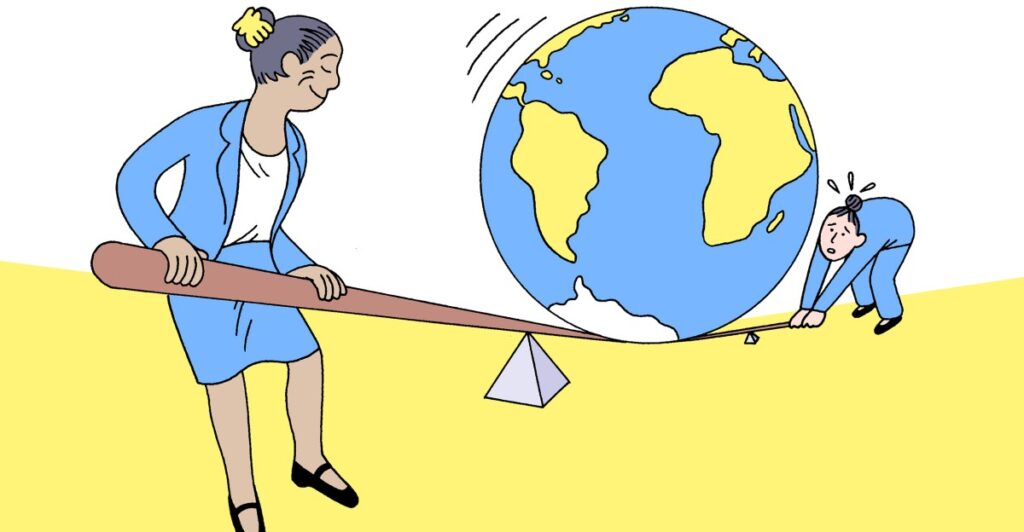

Meanwhile, some of my friends have built their entire careers around the goal of having the biggest positive impact possible. They’re busy pulling big levers — doing global health work that saves lives, shaping federal policy that protects the environment, etc. I feel like my contribution is tiny in comparison.

I know life’s not a competition, but I grew up being told I was smart and had so much potential to change the world, and I worry I’m not living up to that. On the other hand, I also value work-life balance and relationships and experiences outside of work. Should I consider switching careers to something more impactful? Do I need to have an extraordinary career, or is it okay to just do an average amount of good and live a small(ish) life?

Dear Impact-Minded,

How do you feel about the fact that you’re going to die one day?

That might sound like a weird place to start, but I ask because I think fear of our mortality is what drives a lot of our modern quest for extraordinary careers.

In fact, the American anthropologist Ernest Becker argued in his 1974 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Denial of Death, that one of the main functions of culture is to offer effective ways to manage the terror of knowing that we’re going to die and eventually be forgotten.

Key takeaways

- We’ve inherited an assumption that we need to do something “grand” in life. But anthropologist Ernest Becker would say that insistence on achieving a major legacy is just us trying to manage our fear of mortality.

- As Saint Thérèse of Lisieux pointed out, the world would be pretty monotonous if everyone was focused exclusively on the highest-impact ways to do good.

- Instead of obsessing about “doing good,” think about all the “goods” that life offers you. If you start from a place of gratitude, you’ll naturally want to share with others.

The prospect of absolute annihilation is so terror-inducing, Becker argues, that we come up with all sorts of ways to convince ourselves we can achieve immortality. In the pre-modern era, most people looked to religion for this. It promised us literal immortality, in the form of an eternal soul that could enjoy a happy afterlife in heaven, or maybe a nice reincarnation here on Earth.

In the modern era, as religion’s dominance waned, we’ve had to come up with new types of “symbolic immortality.” That can come in the form of publishing an autobiography, being part of a great nation, or — especially popular starting in the 18th century — achieving social progress “at scale.” As the Industrial Revolution propelled globalization and it became possible to think about affecting people halfway around the world, utilitarian philosophers argued that our actions are good to the extent that they create “the greatest happiness for the greatest number.”

The idea that we could use our working lives to maximize the good gave people a new way to be extraordinary and thus achieve a lasting legacy — that is, a sense of immortality. By belonging to the grand project of social progress, we could live on well past our physical death.

On the one hand, the tacit promise is comforting: If we all chase these superlative lives, we can participate in the great forever! But on the other hand, it creates a crushing amount of pressure: There’s a sense that you need to be engaged in a maximally heroic quest — otherwise your life is basically meaningless.

Not everyone, however, sees things this way.

For an alternative, consider Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. Born in France in 1873, she only lived to the age of 24, and the last nine years of her life were spent cloistered in a convent. She was an extremely pious young woman who prioritized kindness. But she was acutely aware of her own imperfections and limitations. She didn’t believe she was a great soul capable of great, heroic deeds. She definitely didn’t think her vocation was to have a positive impact “at scale.”

Instead, she developed a very different approach to goodness, which she called her “Little Way.” It wasn’t about trying to reach a wide swath of people. It was about trying to go deep on little, daily actions, infusing every glance and word with the purest love.

When the other nuns in the convent annoyingly interrupted her with chit-chat while she was trying to write, she made sure “to appear happy and especially to be so.” When one made exasperating clicking noises during prayers, she worked so hard to conquer her irritability that she broke into a sweat. She made lots of sacrifices lovingly, and trusted that through that, she could achieve holiness — and, yes, eternal life.

Saint Thérèse compared people to flowers. Although most people want to be a big, showy flower like a rose or lily, she wrote, she was content to be a little flower at the feet of Jesus:

If all the lowly flowers wished to be roses, nature would lose its springtide beauty, and the fields would no longer be enamelled with lovely hues. And so it is in the world of souls, Our Lord’s living garden. He has been pleased to create great Saints who may be compared to the lily and the rose, but He has also created lesser ones, who must be content to be daisies or simple violets flowering at His Feet.

Saint Thérèse became known as the Little Flower. After she died of tuberculosis, her spiritual memoir grew famous. People fell in love with her theology of the Little Way, and she ended up being one of the most popular saints in Catholic history.

I suspect she struck a chord with people because she offered them a strong counterpoint to the idea, which was gaining traction at the time, that it’s not enough to do good — we have to do the most good possible.

But, personally, I’m satisfied neither by the utilitarian perspective nor by Saint Thérèse’s perspective. Both are extremes: one says “you absolutely must do the most good,” and the other says “don’t even bother trying to help more people — just give the few people in your cloister the deepest love possible.”

Yet it’s a feature of our modern life that the fortunate among us have the capacity to go both wide and deep — to consider both scale and other dimensions of value. People who go all-in on just one of these tend to feel regret, whether it’s the effective altruist who’s so focused on helping at scale that he ignores everything else or the monk who spends decades in deep contemplation but doesn’t do a thing to help others.

So, when you consider your own potential, I’d encourage you to consider the full picture. I don’t think you should obsess over finding a career that’ll allow you to do “the most good.” But doing “more good”? Sure! If you can find a job like that, why not?

But as you look around to see whether there’s a job where you could have a bigger positive impact, you have to be mindful of a few things. For one, there are many different kinds of “good,” and you can’t always run an apples-to-apples comparison between them. (Is your current job doing more or less good than, say, being a journalist or an educator? Hard to say.) Also, there’s more to life than just “doing good” — a life well lived includes reveling in other precious things, like art or relationships, so you don’t want a job that’ll bar you from that. Plus, you don’t want a job that’ll be unsustainable for your physical or mental wellbeing or that’ll wreck your integrity by contravening other values you believe in.

Ultimately, what’ll probably work best is settling on a career that lets you achieve a decent balance among multiple criteria: doing substantial good, allowing for a pluralistic enjoyment of all life’s riches, feeling sustainable, and fitting with your values. (And after scanning the landscape, you just might find that the best career for you overall is the one you’ve already got!)

You’ll notice that this doesn’t sound as “grand” as either the utilitarian recommendation or the Saint Thérèse recommendation. But that’s the point: Those are extreme visions of life, and if you ask me, they’re not even really about life at all. They’re about death and achieving a legacy that you think will earn you a kind of eternal life after death. The assumption is that you need to do something “grand” in order to make your time on Earth not worthless.

Have a question you want me to answer in the next Your Mileage May Vary column?

Feel free to email me at [email protected] or fill out this anonymous form! Newsletter subscribers will get my column before anyone else does and their questions will be prioritized for future editions. Sign up here!

There’s a radically different starting assumption available to you: What if life is just a gift, and the time you have on this mysterious, weird, wondrous Earth is inherently precious, even if it’s temporary? When you get a gift — like, say, a box of candy — the point is not to try to make it last forever. The point is to appreciate the candy! To savor it yourself, and also savor the pleasure of sharing it with others.

If we embrace this view, then we don’t feel like we need to do something grand or extraordinary. Life is extraordinary, and living it well means relishing all the goods it offers us — and extending those goods to other beings so they can relish them too. Not out of fear that we’ll be worthless and forgettable otherwise, but simply because we realize we’ve been given talents and resources and, feeling grateful for them, we naturally want to share those gifts with others.

Bonus: What I’m reading

- Were people in the past just like us, with emotions just like ours? Or did sadness, say, feel very different to a medieval peasant than it does to us? In this article, Gal Beckerman explores the fascinating idea of “experiential relativity.”

- “How did choice become a proxy for freedom in so many domains in modern life?” asks this Aeon article. There might be better ways to make people freer than giving them a huge array of choices.

- What a time to be alive! We all now have access to the text that sculpted the personality of one of the world’s major AI chatbots. Behold, Claude’s “soul doc.”

The post How do you know if you’re wasting your life? appeared first on Vox.