The CIA-trained Afghan accused of opening fire outside the White House struggled for years to adapt to life in the United States, sharing his emotional turmoil in previously unreported social media posts that included broken hearts, a biblical prophecy of the world’s end and a declaration that he was quietly crying but so aggrieved he could have screamed.

In his earliest public Facebook posts, which began soon after the U.S. government brought his family here in 2021, Rahmanullah Lakanwal shared nostalgic photos of his homeland that elicited hundreds of likes and comments from his sprawling online network. Beginning in 2023, his posts grew darker and more cryptic, sometimes drawing no more than three or four thumbs-ups.

Lakanwal’s Facebook and Instagram accounts provide deeper insight into the enigmatic father of five now charged with first-degree murder. His shift online paralleled his behavior offline, according to a community volunteer who offered new details about her years working with the family. Lakanwal, she said, began to spend days alone in his bedroom or on cross-country drives. He failed to keep menial jobs, make friends, feed his children, support their educations, pay rent or even sign documents critical to maintaining the government benefits that sustained his family. She feared he was depressed and would harm himself.

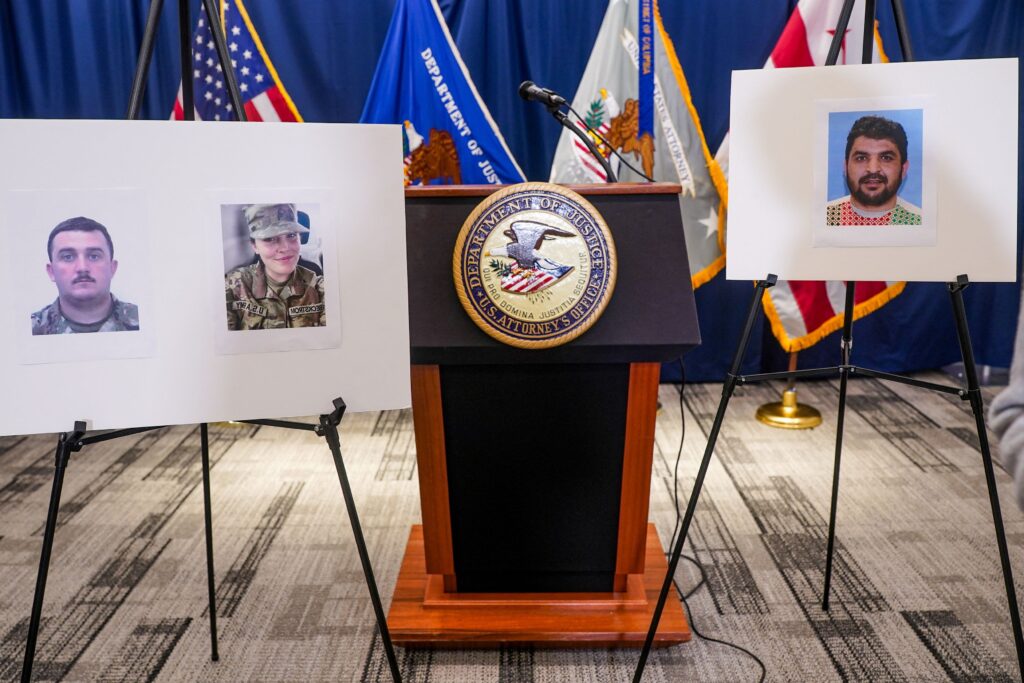

Why Lakanwal would drive 2,800 miles to D.C. and ambush National Guard members on Nov. 26 remains unclear. Charging documents allege that he shouted “Allahu akbar!” as he shot two of them in the head with a .357-caliber revolver.

Lakanwal, 29, is accused of killing Spec. Sarah Beckstrom, who was 20. Staff Sgt. Andrew Wolfe, 24, was critically injured but is expected to survive.

In March of last year, Lakanwal updated his Facebook profile to an image of an Afghan flag alongside the black and white banner of the Taliban, the militant group he battled on the U.S.’s behalf. Between the flags, two arrows bend in a circle — an apparent “refresh” symbol — and a pair of cartoon hands hold a red heart along with a Pashto message: “My dear country, may Allah grant you thousands of blessings.”

Afghan experts who reviewed the image for The Washington Post wrestled with its meaning, divided on whether it showed support for the Taliban or was a more general call for unity in a country that has endured decades of violence.

The community volunteer was stunned to learn about the Taliban flag on his page. Though she could not recall Lakanwal discussing the militant group, the other Afghan men who resettled in Washington often shared disdain for their former adversaries and, she said, wouldn’t have tolerated public support in their ranks.

“Everybody around him would have given him hell,” she said. “These guys’ whole thing was fighting the Taliban.”

The FBI did not respond to questions about his social media accounts, and Meta declined to comment. But Lakanwal’s Facebook page shared a handle with his Instagram account that, at his invitation, the volunteer said she followed for years before it was taken down. On Facebook, he was friends with people verified to be family members, and he’d posted photos of himself, his sons and other children resettled in Washington. The Post also found that he shared identical images to both accounts on the same day.

Hours after The Post contacted the FBI, Meta and the family through an intermediary, the page was deactivated.

For years, Lakanwal’s local supporters had tried to get him mental health treatment, according to the volunteer, who, like others in this story, spoke on the condition of anonymity due to safety concerns. A pair of emails detailing her worries in early 2024 have been widely reported on, but from hours of interviews and through documents, messages and the social media pages, The Post found that his problems were chronic and debilitating.

None of the local community members who worked to support Lakanwal’s family, the volunteer said, knew that he’d served in one of the CIA’s Zero Units, which were assigned to capture or kill suspected terrorists.

After the U.S. withdrawal in 2021, thousands of the men and their families were evacuated to the United States, and according to a former fighter and four other people who worked with them closely, many have found it difficult to adjust, a problem that no government program was designed to mitigate. In many cases, the nonprofits that helped resettle them during President Joe Biden’s administration maintained contact for only two or three months.

Many of the men have struggled to adapt to American bureaucracy, customs and job opportunities, according to the former fighter and the people close to them, who said that several of the group’s veterans have taken their own lives.

“Many members of the Zero Units feel insulted and believe that they were used in Afghanistan, while in the United States neither their documentation nor their future has been clarified. Many of them are facing psychological and economic problems, frustration and depression,” said Rahmatullah Nabil, former head of the National Directorate of Security, the Afghan agency that had nominal oversight of the units.

“Many of them had been wounded during the war, and without a weapon they felt incapable of doing anything else,” said Nabil, who noted that he did not know Lakanwal and in no way defended his alleged actions. “Considering the traditional culture and social structure of the regions around Afghanistan, adapting to the environment and laws of the United States is very difficult for them without proper support, cooperation and supervision.”

In Bellingham, Washington, a college town of just under 100,000 people, the volunteer and her colleagues continued to support the family even as Lakanwal retreated from his responsibilities. She worried that his absence could derail the progress that his boys, who’d all learned English, had made at school.

She last visited his home in mid-November, less than a week before the shooting, but she didn’t bother to look for Lakanwal. He was already gone.

As she pulled up to the apartment building, one of his sons met her outside. She carried the halal chicken and Honeycrisp apples, and he toted the tin of butter cookies. Inside, she dropped off the groceries, shared tea with Lakanwal’s wife, quizzed the kids on their multiplication tables. They asked to play “Candy Crush” on her phone.

No one mentioned Lakanwal, the volunteer said. She was later told he never returned.

An elite fighter, folding blankets

When the volunteer first met him in August 2022, Lakanwal struck her as self-assured, a big personality around whom the room often revolved. He liked to tease the other Afghan men, who seemed to admire and respect him. He tickled and wrestled his boys and showed them how to swing a cricket bat in the driveway. When the other men stopped by, she said, Lakanwal would often invite his older sons to sit on the red floor cushions and listen, grooming them for adulthood.

For the volunteer, visits to the home felt ceremonial. Lakanwal had taught his sons, the oldest now in middle school, to greet her outside and shake her hand. Lakanwal, smiling, would usher her through the door and ask if she wanted to sit on the love seat or the cushions. His wife would bring pistachios and tea. When he spoke, always through an interpreter, he would look her in the eye.

To that point, his public Facebook posts had been unremarkable. He arrived in the U.S. on Sept. 8, 2021, according to a federal record obtained by The Post, and a day later, he shared a photo of himself overlooking what appears to be a green valley in Afghanistan. Months later, a photo of him sitting beside a river drew 94 comments of praise and support.

The family had moved to Bellingham, a coastal city near the Canadian border, around January 2022. Like thousands of other Afghans brought to the U.S., they were eventually placed into subsidized housing, enrolled in Medicaid and given federal food benefits. From the start, the volunteer said, Lakanwal struggled to find reliable work, a pervasive problem among the Afghan men who’d moved to Washington. The vast majority of the jobs in the community that paid close to a living wage — from scrubbing floors to delivering bread — required a high school diploma or GED. He had neither.

Sometime in the middle of that year, the volunteer said, he went to work at a commercial laundry, folding linens.

“You’re taking a guy who was a soldier with U.S. forces, and he’s now folding blankets. Repetitive domestic work,” the volunteer said. “And it still wasn’t enough to feed a family on or pay rent.”

He quit against her advice, she said, when the company wouldn’t give him time off for Ramadan, an Islamic holy month.

It was then, in March 2023, that she first noticed a change. The ceremonial welcomes ended. He spent more time in his room. He took longer drives.

Without the vast familial and tribal networks integral to their society, many of the Zero Unit alumni had begun to feel adrift by then, according to American and Afghan officials who remain in contact with them. In traditional Afghan households, the burden of support falls almost entirely on the men, especially in the rural regions where Zero Unit fighters were recruited.

“For generations, they had their house, their fields, their gardens, their village, and then they lost everything,” said a former senior commander in the Afghan military who now lives in America. “In the U.S., they have nothing. But they have a big family to support — five, six kids — and they are like, ‘How can I feed them?’”

Many felt abandoned by the U.S. as they tried to navigate its overwhelming bureaucracy, according to a 42-year-old Zero Unit veteran who served for two decades. At a time when he couldn’t obtain a work permit, the man said, his American contacts — people he’d considered “brothers” — stopped responding to his concerns.

“They just threw us in the trash, you know. They hurt us a lot to be honest,” he said. “It broke my heart. Why they left us like that?”

The senior commander, who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of concern for his immigration status, knew of about a dozen Afghans who’d killed themselves after fleeing to the U.S. during the withdrawal, including former Zero Unit fighters. If Islam didn’t strictly forbid suicide, he suspects many more would be dead.

The transition has been especially hard, he said, for elite fighters who lost the prestige and respect they had earned at home.

Two months after the volunteer noticed the shift in Lakanwal, he posted a picture of himself on Facebook from what appears to be his time in Afghanistan. With a camouflaged truck behind him, he’s wearing sunglasses and dressed in combat fatigues. Pressed against his shoulder is a Kalashnikov rifle, mounted with an optic and infrared laser. His finger rests near the trigger.

“Love you my cousin, you are a lion,” one man commented in Pashto. “Keep your head high.”

‘I would have screamed’

The volunteer was desperate.

It was January 2024, and a personal commitment would soon force her to take a break from helping the Afghan families. In her absence, she wanted others in the volunteer community to know how extreme Lakanwal’s behavior had become — and how badly his family needed help. So she sent two emails, first reported by the Associated Press, that detailed his unraveling.

He seldom responded to texts or calls. He spent days in his darkened bedroom, refusing to speak to anyone, including his wife and kids. He’d twice taken the family car during what the volunteer called “manic” episodes, once traveling to Illinois and another time to Arizona and Indiana. When his wife was away, he didn’t bathe his children or consistently feed them. He hadn’t paid rent in at least six months and had been served an eviction notice. He’d stopped meeting the basic requirements to maintain the family’s government benefits — checking in with a caseworker, applying for jobs, taking English classes — and risked losing the food subsidies his children relied on.

“I personally believe that Rahmanullah is suffering from both PTSD from his work with the US military in Afghanistan, and that he is possibly Manic Depressive, mostly depressive, based on his behaviors,” the volunteer wrote, noting that she was not a mental health professional.

When the family needed him to sign essential paperwork, she said, they sent his toddler to knock on the bedroom door, because Lakanwal’s youngest boy was the only person he’d respond to.

During an excursion a couple months earlier, he shared a photo of an empty road coated in snow. The sky was gray. Atop a screenshot of the image posted to an Instagram account that’s since been taken down, he’d written a message in Pashto about an unidentified offender: “Just for your sake, I am quietly crying. I would have screamed loudly as I have grievances against you.”

The family’s supporters tried to arrange for an Afghan with a mental health background to meet with Lakanwal, but the volunteer said she believed the man was turned away and they never spoke.

A U.S. intelligence veteran who worked closely with Zero Units was not surprised by Lakanwal’s reluctance to speak about his mental health with a civilian. The group’s veterans, the person said, follow a rigid code not to divulge details of their past work or embarrass the CIA. Plus, a stigma around mental health issues persists in traditional Afghan culture.

When the volunteer returned to the family’s lives in summer 2024, little had changed.

During “interim periods,” as she called them, he would emerge from his despondence and try to make up for all that he’d missed, sitting with her and an interpreter for hours as she filled out online job applications for him. Because he knew so little about technology or the internet, she said, he often clicked on spam emails, clogging his inbox with bogus messages she had to sift through.

She asked about his applicable skills and experience, but he never discussed the specifics of his service in Afghanistan, only saying that he worked “perimeter security.”

He sometimes asked about working mall security, the volunteer said, though she knew his inability to speak English would disqualify him. He had learned to say her name and only two phrases: “Hello, how are you?” and “You are welcome.”

That summer, she helped him get a temp job packing boxes at a fish processing plant.

“Is Rahmanullah still working … or has he quit?” she emailed another volunteer, soon learning that he had, indeed, quit.

The interim periods never lasted.

He skipped his children’s school and social events, she said, and that same summer, he missed a green card celebration for another community member. At the party, his sons, dressed in jeans and T-shirts, held Afghan and American flags bigger than they were.

Meanwhile, on Facebook, he posted on disparate subjects, sharing videos of President Donald Trump condemning the 2018 serial bombings in Texas and of U.S. senators discussing the asylum process. In a comment about cricket, he made a racial slur toward Pakistanis. He posted photos of his grinning boys, a lament about hardship and a photo of the poet Gilaman Wazir, a human rights activist killed last year. Lakanwal shared a prayer that Muslims, Christians, Jews and Palestinians would succeed in their “struggle for freedom,” and he shared two videos of an American pastor preaching about the end of the world.

On Facebook, he had 4,700 friends. In the offline world, he was often unreachable.

In a text exchange that September, the volunteer learned that he had neglected to sign a form in time to keep their Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. The coverage had lapsed.

“Sigh,” the volunteer wrote in response, noting that she was still searching for an Afghan therapist who could speak to him in Pashto.

‘They’re all in fear’

As the end of 2024 drew near, Lakanwal complained to his American helpers that he still had not been approved for a Special Immigrant Visa, which are given to certain foreign nationals whose work with the U.S. government could endanger their lives back home.

In a text to another supporter, the volunteer suggested an alternative: “Rahmanullah should apply for asylum as a back up plan.”

With the help of a pro bono attorney, he filed his paperwork in December, according to a federal law enforcement official who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss details of the investigation. In April, he was granted asylum. The shooting raised questions about whether his mental health troubles should have disqualified him, but immigration experts say that the asylum process is primarily designed to weigh whether a person could face harm in their home country because of their backgrounds or beliefs. Serious crimes or links to terrorism can disqualify applicants, but psychological scars almost never do.

After the attack, the Trump administration stopped processing immigration applications from Afghans, and the president called for the U.S. to “reexamine” those who came under Biden.

The shooting and its immediate consequences set off a panic among Zero Unit veterans, according to the member interviewed by The Post. In WhatsApp groups, the man said, he has tried to calm the fears of the fighters who served under him.

“I didn’t sleep for three days,” he said, worried that residency and citizenship would become harder to earn or, worse, that the government would deport them all.

Lakanwal was repeatedly vetted after leaving Afghanistan. The volunteer recalled being told that the family had first stayed on one of the military bases where thousands of Afghans underwent background checks. In August 2023, the volunteer said, she arranged for a van to take the entire family to Seattle for biometric screenings by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Lakanwal would also have been screened when he applied for a work authorization, which he received under the Biden administration, according to a copy of the record reviewed by The Post.

The volunteer said she noticed no signs of a shift in ideology, but she was confounded by the Facebook post featuring the Taliban flag and the revelation that he had obtained a gun.

In a meeting this week with Afghans who knew Lakanwal, the volunteer said, their sentiment about the shooting had shifted from shock to anger.

“Because everyone’s immigration journey is now stopped,” she said, “and they’re all in fear of being deported.”

She seldom saw him during her visits this year, and when he was gone, she assumed he was at the local mosque, out buying cigarettes or on another drive. She’d learned by then that, even in Afghanistan, he spent long stretches away from his family, so they were used to functioning without him.

Over the summer, the volunteer helped persuade him to let one of his sons attend an overnight science camp.

As school approached, she and another volunteer planned to take all five boys shoe shopping — “we’d have to get the bigger kids to help monitor the little ones in shifts,” she texted — but the Lakanwals told her they could make do with hand-me-downs.

Not long after, the volunteers tried to arrange a special outing for a family member, but they needed his permission.

“I’ll ask Rahmanullah again but it will be my 3rd time with no response,” another family supporter wrote the volunteer, along with a crying emoji.

He never responded.

The volunteer said she last saw him during an afternoon visit in September. Lakanwal looked disheveled, as if he’d just woken up. She suspected he didn’t know or had forgotten that she was coming, an oversight that would have been unimaginable when she first met him.

“Hello,” he said, before disappearing back into his bedroom and shutting the door.

Haq Nawaz Khan, Chris Dehghanpoor, Warren P. Strobel, Rick Noack, Jeremy Roebuck and Aaron Davis contributed to this report.

The post Social posts, messages reveal alleged National Guard shooter’s turmoil appeared first on Washington Post.