When Chase Thieme posted “Signs of a Bad Boss” on LinkedIn last month, he drew on his experiences in the military, as a freight conductor and, most recently, with an equipment calibration company. He didn’t name names but listed behaviors such as “[peeks] over computer screens to check work” and “tells you to find busy work.”

Soon after, the 37-year-old said, he was fired. At the end of a meeting when he was asked repeatedly whether he wanted to stay at the firm, his manager said, “By the way, I saw your LinkedIn post,” according to Thieme. Then they terminated him without cause. He could see on LinkedIn that personnel managers at the firm continued viewing the post even after he was fired.

His boss must have seen the post “while he was in the wrong mindset,” Thieme subsequently wrote on LinkedIn. “Made assumptions I was posting about him (shouldn’t matter, this is my personal page and posts were outside of work hours) and fired me.”

The employer, Tescom Calibration, declined to comment on personnel matters.

Thieme considers himself a cautious social media user. LinkedIn was his only account, and he had started posting regularly only this year, sharing job-seeking advice and insights commonly found on the professional networking platform.

“I stay away from social media to stay out of trouble,” Thieme told The Washington Post. “As soon as I go back on it, something happens.”

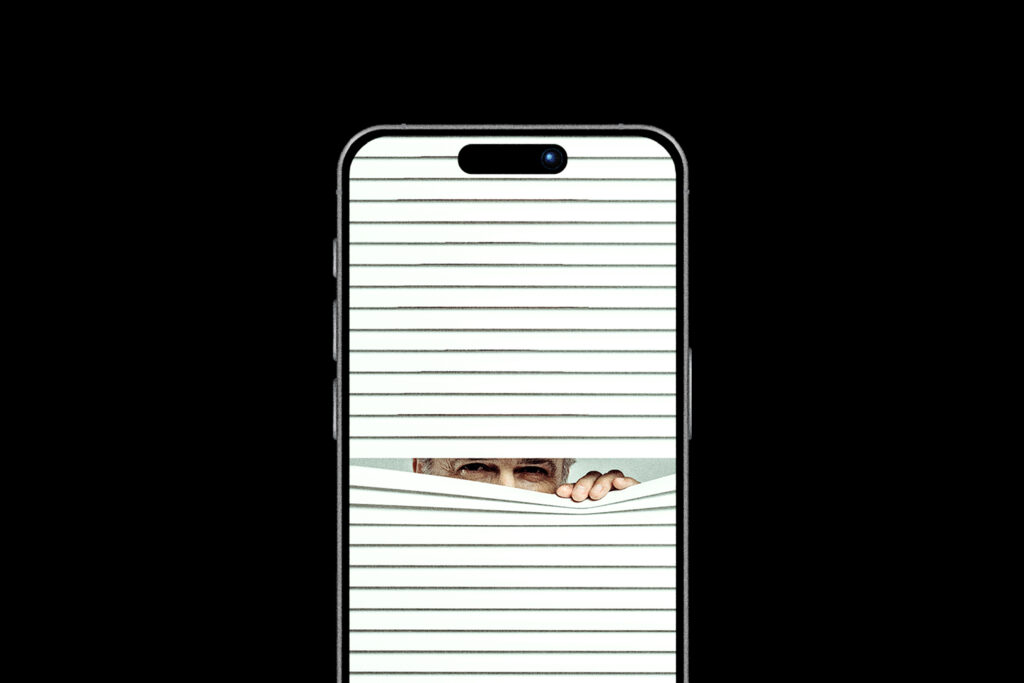

Thieme’s story illustrates how workers are confronting hazy boundaries between permissible and punishable speech as employers clamp down on social media use. Workers are increasingly being disciplined over posts on social or political issues that companies may view as a source of reputational risk, employment experts say, as companies tighten policies and step up surveillance of online activity.

Unease about being drawn into cultural issues has been growing for years among employers, but blowback over posts about the slaying of right-wing influencer Charlie Kirk served as a wake-up call for many, prompting a more aggressive approach in recent months, according to Jim Link, chief human resources officer for the Society of Human Resource Management, the nation’s largest trade group for HR professionals.

Hundreds of employees were disciplined after their posts about Kirk, who was fatally shot in September, sparked public outcry — including from conservative commentators and lawmakers. Reuters reported in November that at least 600 workers — public school teachers, professors, and employees of Nasdaq, Delta and United Airlines, Old Navy and Apple — were investigated, disciplined or fired. Some posts espoused or condoned violence; others did not.

Now, employers of all sizes are “trying to thread the needle” between protecting their brands without making employees feel censored, said Link, adding: “Even if something is meant to be private, it doesn’t stay private. “As a result, more companies are now “proactively monitoring employees.”

“I don’t believe that the concept of private social media exists anymore, and I don’t think a lot of employers do either,” Link said.

Employee speech protections

Sensitivities have become more pronounced since 2020, as the rise of “cancel culture,” coupled with ubiquitous social media use intensified pressure on employers to take public action over matters they might have once let slide, said Adam Goldstein, vice president of strategic initiatives at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a nonpartisan nonprofit. Firms are responding to the phenomenon of social media users — from influencers to lawmakers — banding together to pressure companies on social issues such as diversity, equity and inclusion programs and urging them to punish employees for actions they deem offensive, from participating in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection to posts about Kirk’s death, he explained.

Among headline-making incidents of recent years, an Alaska Airlines hostess said she was terminated over a viral TikTok that showed her twerking in uniform, while a Milwaukee meteorologist said she was let go after criticizing Elon Musk’s inauguration salute.

Alaska Airlines declined to comment on personnel matters but said that “we hold all flight attendants to high standards for conduct and guest care.”

The Milwaukee CBS affiliate did not respond to request for comment.

In the past, “the risk of your employee saying something completely nonwork-related becoming a problem for the business were just lower,” Goldstein said. “Now there’s more tension around the fear of how the public will react.”

Posts weighing in on political and social issues often get workers in hot water, he noted, pointing to workers who were disciplined after posting about George Floyd’s murder, the assassination attempt on Trump and the Israel-Gaza conflict.

Last month, New York’s highest court took up a case in which a lower court sided with a Scarsdale synagogue that fired a teacher after she criticized Israel’s actions in Gaza on her personal blog.

In California, the caseof a Muslim man fired from Microchip Technology — because of pro-Palestinian posts the company deemed “too political” — was recently green-lit for a federal jury trial, court documents show. Kamal Koraitem, a former manager, said he deleted at the company’s request his October 2023 Facebook posts expressing empathy for Palestinians but was still terminated, court documentsallege.

Weeks later, the company added a section to its handbook titled “Social Media Activities Can Impact Employment,” which discouraged managers from posting on “publicly accessible social media accounts.”

“It certainly seems to us like they realized, ‘Hey, our old policy didn’t really seem to contemplate this sort of thing so we’re going to change it so it’s more clear in the future,’” said Zak Franklin, Koraitem’s attorney.

Microchip Technology did not respond to request for comment.

Private-sector employees have very few speech protections, employment experts say. These workers are generally employed at-will, meaning they may be fired with or without cause.

“The First Amendment’s only role in the private sector is to protect employers, not employees,” states a legal primer from law firm Maynard Nexsen.

Still, employers should tread carefully in crafting policies, Goldstein cautioned. For companies, the “more elaborate you make your rule, the more likely people are to argue with it,” Goldstein said.

Public-sector protections

With some limitations, government employees generally enjoy more speech protections under the First Amendment — for example, in cases of whistleblowing or weighing in on matters of public concern, provided that their speech does not disrupt the workplace.

Former professors at Auburn University and Ball State University and a biologist with Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission are among more than a dozen workers who have filed lawsuits challenging their employer’s actions over comments they made about Kirk’s death. At least two plaintiffs have succeeded, including an art professorwho was reinstated at the University of South Dakota and a Tennessee high school teacher.

In November, Erika Santos, who worked as a grant accountant at Eastern Florida State College, filed a lawsuit challenging her firing over Facebook comments about Kirk’s killing. Her activity “was entirely outside of and unrelated to her job responsibilities,” Santos’ attorneys said in court documents, noting that she “addressed issues of public concern.”

Santos’s lawyer, Ryan Barack, of Kwall Barack Nadaeu, said in a statement that through Santos’s lawsuit, “we’re standing up for every public employee whose rights have been chilled by government retaliation.”

Under the National Labor Relations Act, all U.S. workers are protected when discussing working conditions, including pay, benefits and corporate policies, but these provisions are often overlooked by employers who “don’t understand why they can’t have a policy that says you can’t say bad things about the company,” according to Heather Rider Hammond, a Vermont-based employment lawyer.

“It’s one thing to say something that’s untrue, or sexually harassing or objectively offensive,” Hammond said. “It’s another to say, ‘My supervisor really stinks.’”

Thieme, who has since found a new job, said he spoke to nearly a dozen attorneys to determine whether he could challenge his termination. But as a private employee, employed at-will, he came away with the impression that he had “no legal recourse.”

Wide-ranging policies

Micah Saul, a labor and employment attorney with McNees Wallace & Nurick LLC, said this recent crackdown comes as many companies have “peeled back” from weighing in on political and social issues, given that “the folks who are paying for their products or services might not share their opinions.”

But monitoring workers’ social media activity around-the-clock is taxing and impractical given how much of life is lived online, Saul said. “Even if you do have those resources … you don’t want to be Big Brother,” he added.

Large employers and firms in white-collar fields tend to be the most restrictive, according to Gerald Maatman, an employment attorney with Duane Morris, who works mainly with Fortune 1,000 companies.

Some of these clients “do have people assigned all day long to simply monitor the company’s presence” in the news and on social media, Maatman said. In contrast, start-ups or younger firms, and companies whose employees aren’t interacting directly with clients and customers, usually have more relaxed policies.

At software giant SAP, employees “are asked to be cautious when sharing personal views online” and are “encouraged to make the distinction when they share personal views that these are their own and not on behalf of SAP,” according to Megan Smith, head of people and culture for SAP Americas.

“Behavior considered contrary to the company’s values and code of conduct may have adverse reputational effect on the company,” Smith said. “Today, there is rarely such a thing as truly ‘private’ online spaces.”

Hammond works primarily with small- and medium-size employers, many of whom are just beginning to put social media policies in place. She finds that these employers “either have not thought about having a social media policy” until now, or they’ve held off because they “don’t want to be the in business of telling employees what they can and can’t say.”

“The reality is, if something happens and someone does something or says something that’s objectively offensive, you’re going to have to make a decision in the moment,” Hammond said. “With no policy, it becomes a little hard.”

The post How companies are cracking down on workers’ social media activity appeared first on Washington Post.