Towering granite spires whiz by in the background, and Joseph Brambila howls with delight, in a YouTube video he shot of himself sliding on his butt down a steep, snowy slope on the upper reaches of Mt. Whitney.

When he loses control and wipes out — repeatedly — it looks like he’s tumbling inside a snow globe.

He has none of the usual safety equipment for such a slide, known to mountaineers as a “glissade”: no helmet and, crucially, no ice ax, which is used as a brake to avoid picking up too much speed and hurtling into a catastrophic fall.

But he’s lucky. It’s a warm, sunny day in June and the snow is so forgiving he can stop by simply digging his heels into the soft slush.

Even so, while drying his clothes in the sun at the bottom of the 1,500-foot slope, the charming, slightly mischievous 20-year-old confesses to his camera, “Low key, I didn’t know how that was going to turn out. Half of it was good and then way too much speed.”

Brambila returned to Mt. Whitney on Nov. 11, two days after his 21st birthday. At that time of year, the weather can change without warning, quickly turning a soft slope into something much harder, much faster and absolutely merciless.

One of the last people known to have seen Brambila — Luis Buenrostro, a fellow solo hiker who met him on the summit that day — told The Times the two parted ways at Trail Crest, the spot from which Brambila glissaded in June.

The temperature was plummeting and the sun sets early in November, so Brambila indicated he was going to try the “short cut” to save time. Buenrostro assumed he intended to glissade.

Nobody has seen or heard from Brambila since. His family reported him missing a few days later, and other hikers have reported seeing a body on the broad slope that descends from Trail Crest.

But despite multiple searches by state and local emergency services for Brambila — from the air and on the ground with a cadaver dog — no body has been recovered.

In late October, another hiker had fallen and died on that same stretch of trail.

Brambila’s family members have spent the last month posting desperate appeals on social media for help finding him, but the Inyo County Sheriff’s Office is urging caution.

“Heavy snow from the last two storms has made conditions extremely hazardous. The terrain is icy and unstable, and attempting a summit or any search in these conditions is very dangerous,” Lindsey Stine, a spokeswoman for the Inyo County Sheriff’s Department, wrote in an email.

Another search is possible in the coming days, Stine wrote in an email on Wednesday, depending on the weather and the availability of other agencies to assist. But she has also cautioned, “recovery may not be feasible until the snow and ice begin to melt.”

So far, it’s impossible to know exactly what happened to Brambila. Despite the forbidding odds, the people closest to him are “holding on to hope” that he is somehow still alive, his girlfriend, Darlene Molina, said in an interview last week. “We still have faith,” she said.

“He just wanted to be out there”

Brambila had a lot of faith, too.

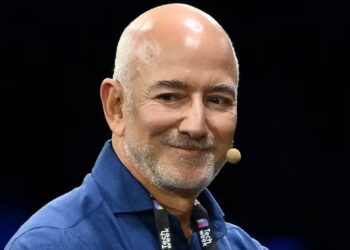

A picture of the budding alpinist emerges from interviews with people close to him, hikers who met him on the trail and, especially, his self-shot YouTube videos. He is a funny, self-deprecating young man from southeast Los Angeles County who is still finding his way in the mountains, but is hopelessly in love with them.

“He always said he loves to disconnect from the real world,” Molina said. “He just wanted to be out there and enjoy life. … It was just him, nature, and God.”

Brambila was especially enamored with Mt. Whitney, the 14,500-foot giant four hours north of Los Angeles and the nation’s tallest mountain outside of Alaska.

Even in perfect summer weather, the standard route up Mt. Whitney is a physically demanding, 20-mile round-trip hike that climbs more than 6,000 vertical feet. It takes some very fit people two long days to complete.

In any other season, the mountain is subject to sudden and severe blizzards. Once buried in snow, climbing Mt. Whitney is no longer a simple hike. It’s a full-blown mountaineering expedition.

The trickiest seasons are the spring and fall, when the snow is least stable and conditions are constantly changing.

Before his fateful November climb, Brambila had tried Mt. Whitney four other times, including one early aborted attempt when his mom insisted on going with him, and another, in April 2024, that’s the subject of a video he posted on YouTube.

It begins with him chiding himself for forgetting his trekking poles in the car. Then he goes over a gear checklist posted at the trailhead: emergency blanket, first aid kit, headlamp & extra batteries, map & compass. He taps each item, saying, “Nope, nope, nope, nope.”

As he turns and starts heading up the trail he quips, “So I think we’re pretty qualified for the hike.”

Not surprisingly, his adventure bogs down as soon as he reaches the snow line and realizes the trail is completely buried. Then he starts post-holing: falling through the surface of the snow up to his knees, sometimes up to his hips.

He’s mostly good-natured about it, joking, “I gotta make myself light!” But some of the falls look painful. At one point, he tells his YouTube viewers how easy it would be to break a leg.

It’s not clear he understands all of the risks he’s taking.

More than once, he crashes through what appear to be snow bridges: spans covering pools of water and running streams. He doesn’t go completely through them, but if he had, there’s a good chance he would have been trapped. Drowning or freezing to death would have been serious possibilities.

After a frigid night camping on a rock ledge — watching YouTube sensation Mr. Beast on a laptop, warming his bare feet by an open fire — he decides to turn around and go home. “Kinda sucks I ain’t gonna reach [the summit],” he tells the camera, “but I’m gonna put my own safety over anything right now, cuz it’s cooooold.”

Was he reckless? Definitely. But he was also a city kid working as a dental assistant who didn’t grow up with endless amounts of money and free time to spend on private guides or expensive mountaineering classes.

So, like many others who are drawn to high alpine peaks with little previous exposure to them, he appeared to be figuring things out on his own.

Buenrostro, the fellow hiker who met Brambila on the summit in November, said he felt an immediate kinship with him. They were both young Latinos from working-class backgrounds who sometimes felt judged by well-off, suburban outdoorsy types for not having all the latest and greatest equipment.

“I understand, sometimes we go out there without all the right gear,” Buenrostro said, “but a lot of the time, we’re saving up for the proper gear.”

The first time Brambila reached the summit of Mt. Whitney was in June, when he posted another video to YouTube. (He labeled the video 7/14/25, but Molina said that was a typo, the trip had been a month earlier.)

In his description beneath the video, Brambila bragged that he climbed the steepest and most dangerous part of the route, known as “the chute,” with none of the standard safety equipment: crampons, ice ax, trekking poles.

Instead, he scaled the 1,500-foot-high snow slope with just “will power,” he wrote. “Honestly it was lots of fun,” he added.

On his way down from the summit, the video shows him running into another group of climbers at the top of the chute. They’re preparing to slide down on their butts.

A chance to glissade feels like a godsend to exhausted hikers, who have often been on their feet for hours. Done carefully in that spot, with the right equipment and in favorable conditions, it can cut at least an hour off the otherwise arduous descent down the section of trail known as the 99 Switchbacks.

But things can go very wrong, very quickly, which makes glissading one of the leading causes of serious injury and death among mountaineers, according to the American Alpine Institute.

From the video, it seems like Brambila has never done it before, but he’s excited to give it a try. He watches, nervously, as the more experienced and better equipped climbers take off one by one. He turns the camera to himself and worries aloud about having no ice ax — but that doesn’t stop him.

An unnamed hiker, who is holding an ax, turns to Brambila before he starts to slide and half-jokingly says, “I hope this isn’t the last time I see you, Joe.”

No ice ax was “a poor choice”

Dave Miller, owner of International Alpine Guides in nearby Mammoth Lakes, has been teaching mountaineering skills on Mt. Whitney, and other famous peaks around the globe, for decades.

His reaction, after watching Brambila’s June video at The Times’ request, was a sympathetic, “Oh God.”

First, he noticed that Brambila seemed to be confused and exhausted at the summit, classic signs of altitude sickness, something he has to watch for in his clients all the time.

Brambila “wasn’t looking good at all,” Miller said. And when someone is that fatigued at the summit, their judgment gets compromised.

Deciding to glissade without an ice ax was “a poor choice,” Miller said, diplomatically. But he quickly added that he did the same thing the first time he tried it.

It was decades ago, he said, long before he became a professional guide. He sat down in the snow, pushed himself to gather speed and then rocketed downhill much faster than he expected. Luckily, there were no rocks or trees in his path and the slope was relatively short, so he reached a flat section and stopped before anything terrible happened.

Since then, he has seen grizzly injuries due to glissading gone wrong.

On Mt. Shasta, in Northern California, he once found a guy who had attempted to glissade down a hard, fast 2,000-foot slope while still wearing crampons on his boots — a cardinal sin.

After he got moving quickly, he accidentally caught one of the metal spikes in the snow, and immediately started cartwheeling down the mountain. He arrived at the bottom of the slope stark naked, all his clothes torn off in the fall, with his ice ax jammed completely through his thigh, like a skewer.

He survived, but it took him months to walk again.

“I get it,” Miller said, “there’s a lot of allure to getting down quicker and easier, instead of trudging down on foot,” but you have to carefully consider the risks.

Like Miller, Brambila appeared to have come through his first glissading experience in June unscathed, but that was probably down to luck and soft snow.

For now, it remains unclear what led to Brambila’s disappearance in November. It’s possible the question won’t be answered until the spring thaw, and even then, there might not be enough evidence to say for sure. The body seen lying on the mountainside, and now buried under many feet of snow, might not even be his.

But it’s likely he tried to glissade again, according to Buenrostro.

The sun was shining warm and bright when the two met at the summit. But before long, clouds started rolling in and the temperature began to plummet, Buenrostro said. He was eager to get down before the early sunset.

He met Brambila again at Trail Crest. Buenrostro was nearing the end of an epic through-hike from Canada to Mexico, so he planned to descend to the west and camp for the night at lower elevation, on flatter ground, but still in the mountains. Brambila was going back to the Mt. Whitney trailhead, so he was headed east.

Before they parted, Brambila asked, “Hey, do you mind if I pray for you?” Then he gave Buenrostro “a little side hug,” Buenrostro said. “It was nice, it was wholesome.”

Buenrostro was worried about Brambila attempting to glissade without a proper ice ax — he had a gardening hatchet instead, the kind you might use to chop wood, Buenrostro said — but he decided not to lecture the younger man.

“I didn’t want to be that person to Joseph,” Buenrostro said. “He said he was gonna be good, so I thought, he’s gonna be good.”

A month later, Brambila’s whereabouts remain a mystery, but all of the clues point to disaster. His black Nissan Sentra is in the parking lot of the Mt. Whitney trailhead, almost completely buried in snow.

The post A young hiker has been missing for a month on Mt. Whitney. Are time and hope running out? appeared first on Los Angeles Times.