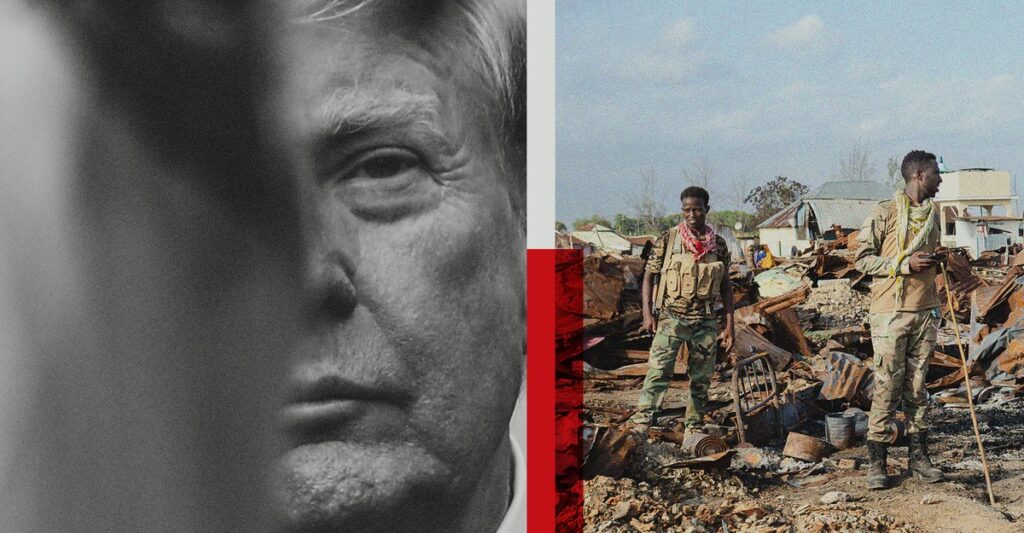

Somalia, where two terror groups are locked in a long-standing battle, should have been an ideal place for President Donald Trump to showcase his “America First” commitment to international disengagement. The country is 8,000 miles away, and its conflicts pose no obvious near-term threat to national security. Interventions in Somalia have already cost the United States hundreds of millions of dollars in the past decade—and even so, the security of Mogadishu, the capital, remains tenuous at best.

Trump himself has suggested that now is the time to get out. Speaking in September before hundreds of generals and admirals gathered at Marine Corps Base Quantico, he cited Somalia as a place politicians have wrongly thought they should police “while America is under invasion from within.” Earlier this month, Trump was even more disdainful, saying that Somalia “stinks” and the country is “no good for a reason.”

Yet just one week earlier, according to local media, dozens of U.S. Special Forces soldiers in northeast Somalia killed at least five suspected members of ISIS-Somalia, an Islamic State affiliate, during an hours-long gunfight. (United States Africa Command, which is responsible for U.S. military operations on the continent, has not publicly confirmed its forces were there.) That was on top of the more than 100 U.S. missile strikes in Somalia so far this year, a much higher pace of attacks than either the 51 strikes during the entire Biden administration or the 219 strikes over the four years of Trump’s first term, most of which targeted ISIS-Somalia’s rival al-Qaeda affiliate, al-Shabaab. President Barack Obama launched 48 strikes in the country during his two terms, according to statistics from New America, a think tank based in Washington, D.C.

Trump has said that his “America First” approach to foreign policy includes employing transactional diplomacy to benefit the U.S., stopping other nations from “taking advantage” of American support, and using force to defend the Western Hemisphere. But events in Somalia suggest that “America First” often looks very different in practice, especially when it comes to the use of the military. Trump may have avoided sending large numbers of troops to war in operations oriented around nation-building. But he has aggressively intervened in conflicts around the world, typically with a torrent of expensive air strikes launched from out of harm’s way or with the deployment of small groups of Special Forces.

The missions are couched as defending the homeland, but their precise goals and results are rarely explained. Starting in April, the U.S. stopped releasing initial estimates of casualties in Somalia, either saying that no civilians were killed or not addressing the issue at all. The military has not announced the death of any top leader of ISIS-Somalia or al-Shabaab, the more powerful of the two groups, since the first strike of the second Trump administration, on February 1. Instead, the targets receive vague descriptions—“weapons dealer,” “terrorist network,” “ISIS terrorist”—or have no identifying characteristics. More often, the press releases about these missions say only which of the two Islamist groups was targeted.

The administration also has not been consistent in limiting its application of “America First” to either imminent or potential threats. Before its Somalia campaign, the U.S. military struck hundreds of Houthi-rebel targets in Yemen in operations costing more than $1 billion. Top administration officials in a Signal group chat questioned whether the United States should be trying to liberate a commercial-shipping channel from persistent Houthi attacks, a bigger issue for Europe than for America. “I just hate bailing out Europe again,” Vice President J. D. Vance wrote in the chat, which also inadvertently included Jeffrey Goldberg, the editor in chief of The Atlantic. The strikes were inconclusive at best: Houthis remain in control in parts of Yemen, and commercial ships continue to avoid the Red Sea.

The U.S. now is also considering strikes that could lead to the ouster of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s government. The administration claims that drug smuggling from Venezuela poses a threat to the U.S.—hence the more than 20 strikes launched on small boats in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific since September 2, which have killed more than 80, even though Venezuela is not a source of fentanyl, the leading cause of drug overdoses in the U.S.

During a December 2 Pentagon briefing, the spokesperson Kingsley Wilson defended the mission in Somalia and said that the administration does not want to focus solely on imminent threats to U.S. borders and in its hemisphere. “We’re not seeking regime change, or, you know, we’re not nation-building,” she said. “We’re not isolationists. We’re also not neocons. We’re realists.”

American interest in Somalia has followed the trajectory of U.S. foreign policy writ large over the past three decades. In the early 1990s, the mission there was largely humanitarian. But in 1993, the United States participated in a military operation to capture the warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid, who had been blamed for the death of dozens of United Nations forces. Local militia shot down two American Black Hawk helicopters, leading to the death of 18 U.S. troops, and the operation became widely known by the title of the book, and later the movie, it inspired, Black Hawk Down. After 9/11, the U.S. began conducting the counterterrorism strikes that continue under Trump.

Previous administrations, including Trump’s first, frequently targeted al-Shabaab, which controls about one-third of Somalia and threatens to overthrow the federal government. Trump’s second administration splits its missile targets between al-Shabaab and ISIS-Somalia, which has a few hundred members in the country’s north.

In September, Trump’s top general for military operations in Africa, General Dagvin R. M. Anderson, made one of his first trips to Somalia, a sign that the nation of 19 million would be a priority. During his July confirmation hearing, Anderson said that he would focus on al-Shabaab and ISIS-Somalia because, if they built capacity, they could threaten U.S. interests and eventually the homeland. He didn’t say why he was so certain. Neither group has said it has designs on the U.S., only that each aims to control Somalia.

The missile strikes have met the legal standard for use of military force under the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force resolution, which allows the president to strike groups associated with terror forces that were involved with 9/11. But the strikes don’t appear to comply with Trump’s professed approach of limiting U.S. intervention to imminent threats—a threshold that presidents often cite to justify the use of force without their consulting Congress or engaging in diplomacy beforehand.

[Read: Trump says he decides what ‘America First’ means]

The U.S. military in the past has said that its strikes in Somalia aimed to improve regional security. Today, military commanders typically couch the strikes in the language of “America First,” saying they have targeted groups that “threaten the U.S. Homeland, our forces, and our citizens abroad.”

Whether this has been the case is not always clear, however. On September 13, U.S. missiles landed in Badhan, which sits at the front line of contested territory between the Puntlund region of Somalia and the breakaway republic of Somaliland, eliminating what a subsequent press release termed an al-Shabaab “weapons dealer.”

Local reports said the target was Omar Abdullahi Abdi Ibrahim, a tribal leader and influential elder who had maintained relations with al-Shabaab but was not involved in terrorism. Ibrahim was driving when three missiles struck his car, leaving nothing but metal shards and bone fragments, according to local reports, which quoted herders who had been nearby. Residents across the region staged protests. They claimed that Ibrahim had been meeting with government leaders and expressing his opposition to a proposed deal that would allow the United Arab Emirates access to mineral deposits in the nearby Cal Madow Mountains. The U.A.E. along with Kenya, Ethiopia, Turkey, Qatar, and Egypt are all seeking influence in the Horn of Africa.

Not every ISIS or al-Qaeda affiliate operates in the same way or for the same aims—or even has its sights set on the United States. Both al-Shabaab and ISIS-Somalia are local insurgencies.

The Africa Center for Strategic Studies, a Defense Department group funded by Congress, says that al-Shabaab aims to be a “totalitarian theocracy in Somalia.” ISIS-Somalia, in contrast, has struggled to gain territory and expand its army of fighters as it battles al-Shabaab and the Somali federal government. “We simplistically hear the name ISIS and immediately assume that the group is a threat to the U.S.,” Will Walldorf, a professor of politics and international affairs at Wake Forest University, told me. “Some have gravitated to the name to raise funds and recruit, but they are not comparable to the ISIS we knew in Iraq and Syria at the height of the caliphate.”

The U.S. strikes are having some effect. ISIS-Somalia, in particular, is worse off, J. Peter Pham, who served as a special envoy for Africa during Trump’s first term, told me. “Is the world a better place without them? Yes. Are they worth the price of whatever munition is dropped on them? Maybe not,” Pham told me.

Leaving terror groups alone is hard to politically defend, however remote their threat might be. The aims of al-Shabaab and ISIS-Somalia are akin to that of the Taliban in Afghanistan, which arguably posed no direct threat to the U.S. yet hosted Osama bin Laden, the architect of the September 11 attacks. But the groups in Somalia are not close to reaching their goal of controlling the country.

Sebastian Gorka, who heads U.S. counterterrorism operations at the White House, told the Hudson Institute in August that when he returned to government he was surprised by ISIS’s expansion across Africa, which he described as the group’s new base of operations after it lost havens in the Middle East. Because of that, he said, the U.S. needed to embrace a hawkish strategy to keep terror groups from metastasizing. Gorka declined to comment for this story. (“Atlantic are scum. No thanks,” he wrote in response to my request.)

U.S. Africa Command, in a statement, didn’t address why the U.S. should be worried about al-Shabaab or ISIS-Somalia, or articulate the specific aims of the U.S. strike campaign. “Our strategic approach to countering terrorism in Africa relies on trusted partnerships and collaboration grounded in and through shared security interests,” the statement said. “The cadence in conducting airstrikes in Somalia reflects that strategy.”

The administration’s National Security Strategy, released December 5, specifies the major threats against the United States. The document says that the U.S. “must remain wary of resurgent Islamist terrorist activity in parts of Africa while avoiding any long-term American presence or commitments.” It also says that the U.S. should “partner with select countries to ameliorate conflict” and “foster mutually beneficial trade relationships” to harness “Africa’s abundant natural resources and latent economic potential.” The document, which also calls for the U.S. to turn away from the Middle East and Europe, cites Somalia once, as an example of where the U.S. could prevent the rise of new regional conflicts.

No one group controls Somalia now. President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud holds Mogadishu, but clan militias, al-Shabaab, and, to a lesser degree, ISIS-Somalia control much of the countryside. The autonomous Somaliland region controls the country’s northwest. There are also several federal member states that operate semiautonomously.

[Read: The boat strikes are just the beginning]

During his first term, Trump withdrew all 700 troops who were based in Somalia. President Joe Biden brought back roughly 500, a level that the second Trump administration has maintained. The deployments have helped train Somali special forces and support local troops, but not enough for them to stabilize the country.

“The Somali National Army (SNA) is still incapable of sustained clearing and holding operations,” according to a report last month by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, and “suffers from a host of troubles, including poor leadership, corruption, uneven training standards, and a reliance on clans deemed loyal to a sitting president rather than being a force having a genuinely national character.”

If Somalia is on the brink of collapse—politically, economically, and constitutionally—air strikes alone cannot fix that, Pham said. Training security forces is not enough. What the U.S. needs is a comprehensive review of its policy. Maybe supporting the government in Mogadishu is not worth it for the U.S., Pham explained. Different investments—for example, in the government of Somaliland, which holds elections and has kept terror groups at bay—might provide the U.S. with a better strategic return on its investment.

Without international follow-up on the ground that tackles governance issues and a stronger national Somali military, U.S. missile strikes won’t address the root causes that create the conditions for civil war, such as poor governance and corruption. Rather, Walldorf said, they “could create conditions for the kind of animosity and anger that could lead to the next generation of jihadists.”

Marie-Rose Sheinerman contributed research for this article.

The post So This Is What ‘America First’ Looks Like appeared first on The Atlantic.