The Rev. Guilherme Peixoto was sitting down for dinner the night before a high-profile DJ gig in Slovakia — a combination youth festival and birthday celebration for the archbishop of Kosice — when the church’s production team began to buzz with excitement.

They had a new opening act: Pope Leo XIV.

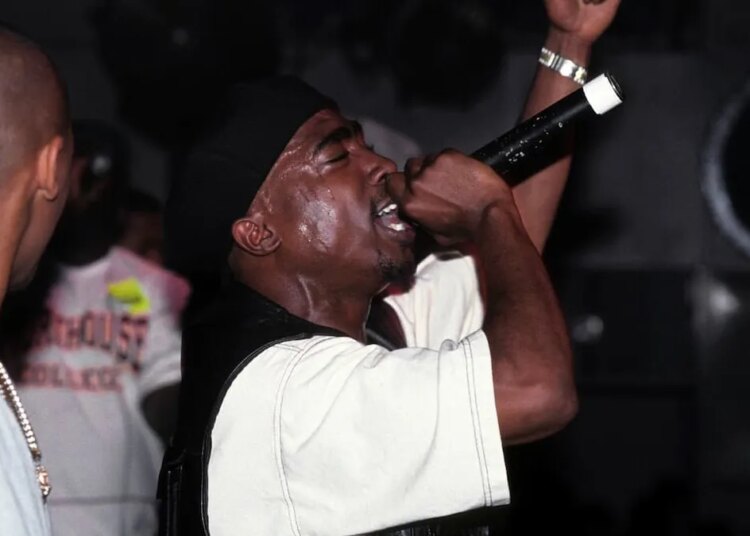

Peixoto, a 51-year-old priest and DJ based in Braga, Portugal, scrambled to adjust. For nearly two weeks before the November event, he had pored over melodic techno beats by Slovakian music producers and selected popular hymns in Polish and Slovak. Now he had to incorporate a special video message from the Holy Father that the Vatican had sent to surprise the archbishop.

“I said, ‘Yes, okay, I need to work this [in] for tomorrow,’” Peixoto recalled in a Zoom interview last week.

With members of his production team, Peixoto worked through the night, adding tracks of synthesizers to the pope’s address, mixing and mastering, and waking again at 3 a.m. to finish.

That evening, fog wafted around the dramatically lit St. Elizabeth’s Cathedral in Kosice as Pope Leo’s message played on a video screen to swirling synthesizers. As the Pope’s “Amen” echoed over the crowd, lights flashed and the music built.

Then Peixoto dropped the beat.

Video of the set’s openingwent viral, drawing more than 10 million views on Instagram alone. The staging was so dramatic, the scene so unlikely — a gothic cathedral, a DJ priest, the pope — that many viewers questioned if the clip was artificial intelligence.

To the contrary, Peixoto said he’s chasing real-world connection with his DJing, which he calls “the project.” At a time of growing social isolation among the world’s youth, Peixoto is optimistic about the power of dance music to amplify the message of God’s love.

Parties pay the parish debt

Peixoto knew he wanted to become a priest long before he started spinning crowds into a tizzy with samples of “Ave Maria” and the Super Mario Bros. theme song and bobbing along to house music alongside sunglass-wearing acolytes.

But he also liked nightlife, gravitating in his youth to underground house and techno scenes of artists like British house DJ Carl Cox and Detroit techno producer Jeff “The Wizard” Mills. In seminary, Peixoto continued to visit clubs and play in a band with his fellow seminarians, all of whom assumed they would quit music once they were ordained.

Peixoto started life as a priest in 2001 in Póvoa de Varzim, a Portuguese resort town roughly 20 miles north of Porto. His bishop soon asked him to take on another nearby church, which was struggling with debt and in need of repairs.

To raise money, Peixoto decided the church should open a small parish bar during summer. Soon, the church had added music nights of parish choirs and karaoke.

“But calm music, romantic music, it is not good for business,” Peixoto said. “People want to sing, people need to dance to have fun.”

Peixoto controlled music from his laptop, slowly expanding his rig and his DJing skills. Within three years, he said, the parish had paid off its roughly $29,000 debt in its entirety.

A self-described “perfectionist,” Peixoto wanted to professionalize his DJing further by learning how to organize a set and produce music. So in his 40s, he signed up for a DJ school in Porto, where he was quickly humbled by his fellow classmates, many of whom were children.

“I was furious sometimes because they were learning much faster than me. How is it possible these kids can mix so well?” Peixoto said, laughing.

Occasionally, his DJ lessons had to take a back seat to his clerical duties, like when he apologetically told his teacher he had to leave class.

Peixoto recalled explaining: “Someone died in my parish, and I need to organize the funeral.”

Sacred music everywhere

While a techno party priest is exactly the kind of unexpected mash-up that takes social media feeds by storm, the Catholic Church has a long history of tapping into secular music, said Andrew Gill, a producer and co-host of the podcast “Rock That Doesn’t Roll: The Story of Christian Music.”

It was the church’s 1960s effort to modernize worship with the Second Vatican Council that prompted congregations to swap pipe organs and Gregorian chants with guitar-backed hymns sung in English, Gill said. One of the most popular films of the era, “The Sound of Music,” captures the way secular music can be a kind of vehicle for praise, he said.

“You have a nun just being so in love with the world and God, and seeing it all as one thing,” he said. “It’s a tradition that I can see coming all the way through to this DJ, [Peixoto].”

And for as much as traditionalists might blanch at a clergyman surrounded by the trappings of nightlife, the two ideas aren’t in conflict, said David Dark, professor of religion and the arts at Belmont University.

If the church exists to proclaim the Gospel and the kingdom of God, there is no division of secular and sacred, Dark said, including in music.

“There is no ‘secular’ molecule in the universe. There is no dandelion owned by the devil,” said Dark, author of “Everyday Apocalypse: Art, Empire, and the End of the World.” He added that the idea that Peixoto is suddenly bringing religion into a nonreligious space doesn’t work, if you believe — like poet Gerard Manley Hopkins — “that ‘the world is charged with the grandeur of God.’”

Trust, faith and headphone blessings

Peixoto, who usually DJs in his clerical collar, has found little conflict in his ministry as the “DJ priest.” He said he’s careful to consider how his roles overlap, evaluating whether a club’s rules or a party’s theme would pose any conflict to him as a member of the clergy. If a festival, for instance, planned to use demonic depictions in its decorations, he said he’d avoid it.

“I think we should be in the world without losing our identity,” Peixoto said. “Most of the people that talk about electronic music, they don’t know what is electronic music.”

He said people who may criticize his association with electronic dance music culture — perhaps linking it with drugs or self-indulgence — have probably never been to a festival or a club: “They are criticizing what they don’t know.”

Like Jesus and his apostles, Peixoto has a team of 12 that supports his music ministry. Money earned from gigs is invested back into the team, with the blessing of the archbishop of Braga, Peixoto said.

Occasionally, Peixoto’s superiors raise questions that they hear from others about the nature of his DJing or where it takes him. Peixoto said he asks them for counsel and is always supported and told to keep working.

“Even if my bishop doesn’t understand everything, he trusts what I do,” Peixoto said.

Though Peixoto has not met Pope Leo, the Vatican acknowledged Peixoto’s dance-floor fellowship last month in a news release about the event at the Cathedral of Kosice. Peixoto did meet Pope Francis on three occasions. On the second of those, Peixoto asked the pope to bless his Sennheiser headphones.

“I don’t know if he knows what is a DJ or not, but I told him that I was a DJ and I asked the blessing of the phones,” Peixoto said. “The bishops, the cardinals, all of them were laughing with the situation.”

Ultimately, Peixoto said, he hopes to help young people experience God’s love through the joy, friendship and fellowship found in music. He wants them to understand, as they struggle for identity and belonging, that — to paraphrase Carlo Acutis, the first millennial saint — they should live not as copies but as the unique originals God made.

“We don’t all need to play the same music, we don’t need all of us to think in the same way, having the same vision,” Peixoto said. On the dance floor, people can be together as one body, united across differences.

These days, Peixoto DJs on professional equipment. He sifts through 200-year-old Catholic hymns and speeches from previous popes and pacifist figures, like the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., to find songs with references relevant to whatever audience he plays for — Fatima in Portugal, the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico or the Virgin Mary in Italy.

The preparation means by the time he starts DJing onstage, his “work” is finished.

“I’m really just enjoying and feeling that God is present, that God is on the dance floor with us,” Peixoto said. “When I’m looking to the crowd, I have this sensation that they are feeling God also.”

The post Priest by day, DJ by night: He uses techno — and the pope — to pump up the pews appeared first on Washington Post.