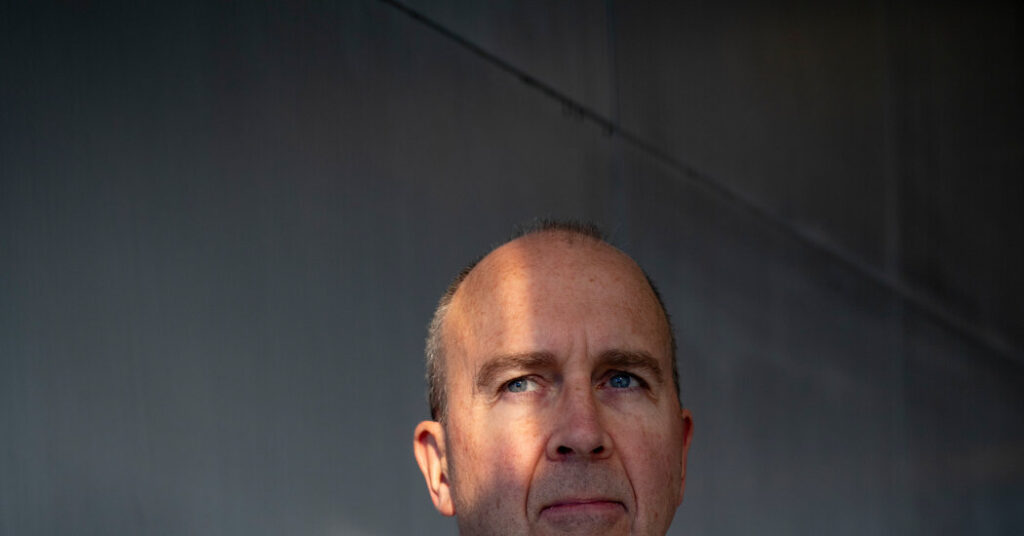

In 2021, after Apple gave up on its secretive plans to build a driverless electric car, Doug Field left the technology company to embark on a mission impossible meant to save the American auto industry.

He rejoined Ford Motor, where he had started his career decades earlier, with the grand ambition of designing electric vehicles that would allow the century-old company to compete with Chinese carmakers, whose vehicles are hugely popular with consumers and breaking global sales records.

Mr. Field knew the old ways of Detroit wouldn’t do. Time was short, and to jolt the storied automaker into action he created an automotive start-up of sorts — a secretive lab near Los Angeles, with a satellite office in the heart of Silicon Valley, that he called a “skunk works.”

He recruited engineers and designers from electric vehicle makers like Tesla, Rivian and Lucid and from start-ups working on batteries, electronics and software, and promised them the kind of creative freedom that tech workers take for granted.

To shield his project from corporate meddling, anyone not on Mr. Field’s select team wasn’t even allowed through the door. No exceptions.

“They got to start over,” Mr. Field said of Tesla, which was established just over two decades ago and effectively created the market for electric cars. “We had to have a place inside of Ford with that opportunity.”

The auto industry is undergoing change the likes of which it hasn’t seen since the early 1900s, when Henry Ford’s Model T and moving assembly line transformed the economy and how people got around. The ubiquitous horse-drawn buggy was consigned to museums, while countless other businesses became obsolete.

Ford and other established carmakers are now staring down that kind of obsolescence, particularly as Chinese companies like BYD and Geely race forward, producing 60 percent of all electric vehicles worldwide.

The best hope is to leapfrog the Chinese by producing better batteries, more efficient electric motors and other breakthroughs and then doing it again and again. And the best hope for making those things happen are people like Mr. Field, who are trying to teach Detroit to be as innovative as Silicon Valley.

“I knew it would be a completely different challenge than anything I’d done before,” he said, “which was to try and change the course of a large organization.”

Nobody knows how this contest will play out, but there are already signs that the Western automakers are falling even further behind. Many of their most innovative and affordable battery-powered models are still years away. Mr. Field’s first vehicle isn’t expected to even go on sale until 2027.

Mr. Field, who has also worked at Tesla and Segway, is fully aware that teams like his have the fate of an entire industry in their hands. More than four million Americans work at car and parts factories, dealerships and repair shops.

President Trump is determined to turn back the clock on electric cars, even dropping strict fuel efficiency standards that favored them. But as most of the world pivots decisively away from the combustion engine, car executives see no choice but to stay the course.

“Most of our sales are outside the U.S.,” said Jim Farley, Ford’s chief executive and Mr. Field’s boss, “and we are running into the Chinese.”

‘Room to Run’

One thing going for the underdog Western automakers is that there is plenty of room to improve how electric cars are made, and there is also no shortage of ambitious entrepreneurs wanting to make a go of it.

One Boston area start-up, AM Batteries, is among several companies working on machinery that can reduce the cost of battery manufacturing. The equipment made by the start-up forms layers of lithium, nickel and other materials into battery cells using a dry powder instead of the wet slurry used in most battery factories today.

The technology eliminates the need for a long drying process, does not generate toxic chemicals, and shortens the assembly line, saving time and money. And, if it can be put to use on a large scale, the company’s approach will make batteries — the most expensive part of an electric car — more affordable.

“What keeps me awake at night is knowing that engineers in China and Japan are doing the same thing,” said Lie Shi, AM’s chief executive.

AM, whose investors include the venture capital arms of Toyota and Porsche, is among dozens of young companies looking for ways to make electric vehicles cheaper and more practical.

Daqus Energy in Woburn, Mass., is trying to make batteries from plentiful organic materials rather than costly metals like lithium, nickel and cobalt. Estes Energy Solutions in San Francisco is developing a way to package battery cells that makes them lighter.

Niron Magnetics in Minnesota is working with Stellantis, the maker of Jeep and other brands, on substitutes for the rare earth metals required for electric motors, so that automakers are not dependent on supplies from China. There are many other examples.

“There is a lot of room to run with these technologies,” said Brian Potter, a structural engineer who recently wrote the book “The Origins of Efficiency.”

As innovative as start-ups are, ultimately the onus will be on Ford and other established carmakers, which are used to incremental change, to overhaul the way they work. Mr. Field’s California team has developed a medium-size pickup assembled in a way that illustrates the kind of innovation that may be the U.S. auto industry’s best hope.

The front and rear sections of the pickup will be cast from molten aluminum in giant machines rather than being welded and glued together from hundreds of pieces, the way most cars are made today.

The method allows Ford to install instrument panels and other interior parts before the large sections are fitted together around a battery. Assembly line workers don’t need to lean awkwardly into car interiors as is the case in most car factories today.

Assembly will be so much more efficient and inexpensive that when the pickup goes on sale it will cost $30,000, Ford said, not much more than the smaller gasoline-powered Ford Maverick.

Mr. Field said one of his former bosses, Elon Musk, the chief executive of Tesla, endorsed his decision to join an established carmaker. “When I told Elon I was going to Ford, he said, ‘That’s good.’”

The stakes are enormous — and not just for Ford.

“Any car company that doesn’t adapt,” said Joachim Post, a senior executive at BMW, “will have trouble surviving.”

Move Fast or Get Run Over

While Chinese cars are effectively barred from the United States by high tariffs and other restrictions, Ford dealers in places like Bangkok, London and Mexico City are already battling Chinese carmakers that offer high-quality vehicles at low prices, Jim Farley, Ford’s chief executive, said in a recent interview in Detroit. If Ford and other U.S. automakers can’t defend their turf, they risk becoming niche manufacturers of big gas guzzlers confined to the United States.

“I have 10,000 dealers around the world. Only 2,800 are in the U.S.,” Mr. Farley said. “So you do the math.”

In Thailand, for example, the Ford Everest gasoline sport-utility vehicle seats seven and starts at 1.2 million baht, or $37,700. An electric BYD M6 can seat six and costs $26,000.

“It’s the biggest battle of my career,” Mr. Farley said.

Mr. Farley’s uneasiness is reflected across the auto industry. Electric vehicles, including plug-in hybrids, account for about 10 percent of new car sales in the United States, but in Europe they account for almost 30 percent and in China more than 50 percent.

If that weren’t bad enough, U.S. automakers are also contending with wild swings in federal policy. Mr. Trump, who dismisses climate science, has reversed auto and energy policies dating from as far back as the administration of George W. Bush.

Innovative technologies could be the salvation of the U.S. auto industry, but only if they are manufactured here. Historically, that has not always been the case. The lithium-ion battery was developed largely in U.S., British and Japanese university and corporate labs. But today the largest maker of lithium-ion batteries for cars is CATL, a Chinese company founded in 2011.

“We have to break the cycle of ‘invent here, scale there,’” said Gene Berdichevsky, chief executive of Sila Nanotechnologies, which last month began producing a new silicon-based material at a factory in Moses Lake, Wash., that significantly increases the amount of energy batteries can hold.

Start-ups in the United States have a built-in disadvantage. The Chinese government provides long-lasting financial and other support to automakers and battery companies as part of a national drive to become a global player.

“The government is completely in bed with the local brands,” Mr. Farley of Ford said.

Innovative firms in the United States do get help from the government but it can be fleeting because priorities often change in Washington. They have to largely depend on private capital, especially after Congress cut or eliminated programs designed to foster electric vehicle manufacturing.

Western companies need to move quickly. They can take as long as seven years to develop a completely new vehicle and set up an assembly line to build it. Chinese manufacturers can get a new model to showrooms in half that time and sometimes even less.

To speed up development of its newest electric vehicle, a sport-utility vehicle called the iX3, top BMW executives visited engineers and designers at their offices every four weeks rather than requiring those employees to troop to headquarters in Munich for approvals.

Teams were encouraged to ignore traditional barriers between corporate divisions. Experts in foam technology who had designed car seats were recruited to find the best kind of foam to insulate batteries so the new model would be fire and crash resistant.

BMW engineers are particularly proud of a panoramic digital display that stretches across the bottom of the car’s windshield, providing driving directions and other information without requiring drivers to take their eyes off the road.

The company plans to begin selling the iX3 in the United States in 2026 for around $60,000. The car will travel 400 miles on a full charge and can be topped off at a fast charger in just 21 minutes.

But in a demonstration of how hard it is to stay a step ahead of China, Xiaomi, a maker of smartphones and cars in Beijing, has begun selling a car with a panoramic display similar to BMW’s. And some new BYD cars can be refueled in less than 10 minutes at ultrafast chargers the company has begun building in China.

Starting Over

At their cloister in Long Beach, Calif., Mr. Field’s team at Ford, which included Alan Clarke, who had been in charge of developing new vehicles at Tesla, threw out the old organization chart. Designers responsible for the vehicle’s aesthetics worked alongside aerodynamics engineers responsible for reducing wind resistance. Traditionally, they had worked in separate offices.

The designers and engineers know that “you both have this job to make something efficient that’s incredibly attractive,” said Mr. Field, who credits his parents for giving him an appreciation for engineering and aesthetics. His father was a chemical engineer and his mother was an artist and musician.

Mr. Field, who lived in Texas, Indiana, Canada and Connecticut while growing up, stuck close to his father’s career path and studied mechanical engineering at Purdue. He later earned master’s degrees in engineering and business at M.I.T.

While Ford took an unusual step in isolating this team far from its home base, other automakers like Mercedes-Benz, G.M. and Honda have also instructed employees to come up with what the industry calls a “clean sheet design” — one that is not encumbered by previous models or ways of doing things.

There are other problems for U.S. automakers in particular. Big vehicles with internal combustion engines like Ford’s F-150 pickup are very profitable because they don’t cost a lot more to manufacture than smaller cars. But people are willing to pay more for a big truck or S.U.V. because they feel like they are getting more for their money.

The same logic does not apply to electric vehicles, where batteries account for a large share of the cost. Making an electric vehicle becomes more expensive with size because of the need for bigger, costlier batteries.

“As they get bigger and bigger and less and less efficient, you have to put bigger and better batteries in them, and it doesn’t scale the same way,” Mr. Field said.

Some analysts say it’s already too late for U.S. automakers to beat China. Instead, they should take the “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” approach and form partnerships with Chinese manufacturers to get access to their technology, said Shay Natarajan, a partner at Mobility Impact Partners, a private equity firm that invests in transportation.

“If I were leading any of the carmakers right now I would focus on partnering with the Chinese,” Ms. Natarajan said.

Dan Cook, the chief executive of Lyten, a San Jose, Calif., battery maker, said he had faith in the creativity and willingness to take risks that has so often put the United States at the forefront of new technologies like computers and microchips.

Lyten is developing batteries made primarily of lithium and sulfur, which is extremely cheap and readily available in the United States. If the company can mass produce it, the result would be cheaper and lighter batteries not dependent on materials from China.

“Silicon Valley is here because of the freedom to innovate,” said Mr. Cook, who started his career at G.M., “and the freedom to think and make mistakes.”

Mr. Field’s task now, he said, is to meld Ford’s century of manufacturing experience with this kind of inventiveness. As the vehicle moves closer to production, he has been allowing more people to cross the skunk works’ moat. The team now has a satellite office in Dearborn, Mich., Ford’s hometown.

“Getting a large company to be able to still produce high volume and high quality, and be able to innovate,” he said, “that would be a force to be reckoned with.”

Jack Ewing covers the auto industry for The Times, with an emphasis on electric vehicles.

The post Hatching the Automobile’s Future in a Cloistered Los Angeles Lab appeared first on New York Times.