Los Angeles County splurged $200 million last year to buy the Gas Company Tower, calculating that moving to the posh downtown address was a steal compared with the $700 million it might cost to make its old headquarters earthquake-safe.

But the decision to leave the historic Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration was based on a half-billion-dollar miscalculation, says a group of experts and politicians trying to save it.

The $700-million estimate was a massive exaggeration, as it relied on one of the most expensive methods of earthquake retrofitting, says developer and preservationist Dan Rosenfeld, who is leading the group.

When it presented the estimate for a retrofit, Public Works “didn’t just put their thumb on the scale” to show retrofitting was too costly, he said, “they jumped on it with both feet.”

Rosenfeld’s lonely group of crusaders has been writing letters and lobbying behind the scenes to urge the county to reconsider its plans, which point to eventually razing the Hahn building. The cost of retrofitting it could be less than a sixth of the estimate the county is using, they say, so the building should be saved to use as offices and possibly housing.

The county does not agree. It reached the correct decision, the chief executive’s office said in a statement, after exploring “a full range of seismic options beginning in 2017.”

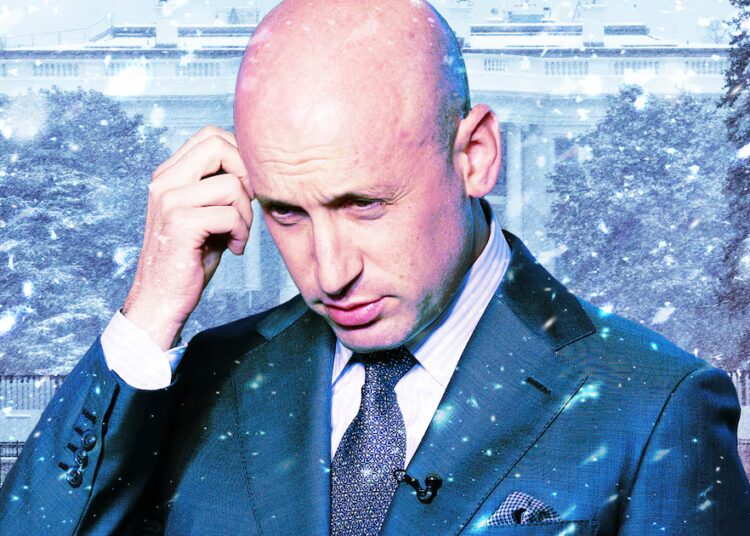

Even though county officials have already started moving into their new offices in the Gas Company Tower, L.A. County Supervisor Janice Hahn says it isn’t too late to save the Late Moderne-style building.

Although the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration is named after her father, Hahn says her campaign isn’t just about family legacy but also about saving money and protecting history and the environment.

“We should take another look at this now,” she said.

Los Angeles County says there are no current plans to demolish the building, but razing much of the structure has been suggested in multiple staff meetings, Hahn said,

The rear-guard action to save the aging building marks the latest twist in an ongoing debate about what to do with a building that lacks the charisma of City Hall and other landmarks but is historically significant and still functional.

The 10-story structure stretches a full city block and faces a landscaped park with fountains, pathways and a coffeehouse. It has been one of the main anchors of the city’s Civic Center of public buildings near City Hall since its completion in 1960. The building was renamed the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration in 1992 in honor of Hahn’s father, who was the county’s longest-serving supervisor and a former Los Angeles City Council member.

In the 1960s, it was considered a crowning achievement in mid-century Los Angeles.

It is less beloved today. Some visitors find its public spaces, filled with brown marble and terrazzo, too institutional.

It also isn’t considered compliant with current earthquake safety standards. The county had planned to seismically retrofit the structure until it decided to buy the nearby Gas Company Tower last year.

One of the main reasons to buy the newer skyscraper for $200 million, county staff said, was that it could cost an estimated $700 million to bring the Hahn building up to seismic codes. Hahn was the only board member to vote against purchasing the Gas Company Tower.

A recent examination by experts estimated that the Hahn building could be brought up to code for less than $150 million, using common techniques used to retrofit other historic Los Angeles structures.

The county should “immediately put a pause on any discussions about the demolition of the Hall of Administration” and allow further study of ways to increase the seismic safety of the building, architect Karin Liljegren said in a letter to the Board of Supervisors.

Liljegren’s firm, Omgivning, specializes in the adaptive use of older buildings.

Tearing down old buildings erases history, in this case a building co-designed by leading mid-century architect Paul R. Williams, and creates waste, she said.

“Imagine a million square feet of concrete and steel just being tossed into a landfill,” she said.

One of Omgivning’s current projects is the conversion of the former L.A. County General Hospital into housing. It’s a massive Art Deco structure dating to the 1930s that no longer met safety standards after the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

It is planned to bring the building up to code for $130 per square foot. If the Hahn building were renovated using the same rate, that would translate to about $150 million, Rosenfeld said.

The county responded that it is still too early to estimate the cost of seismic renovation at General Hospital since the county has yet to receive a complete design and associated cost estimate from the developer.

Opponents of the razing of the Hahn building speculate that the Public Works department chose the most expensive retrofit option because county staff wanted to move to more luxurious quarters. The Gas Company Tower has been one of downtown’s best office skyscrapers since its completion in 1991.

“Who wouldn’t want to move from the third floor to the 50th floor of the best building in town?” Rosenfeld said. “But who benefits? Not the public.”

Hahn thinks the county can save the building and continue operating the Gas Company Tower as a landlord, and maybe sell it later for a profit. The county could also use it for temporary office space while the Hahn building is renovated, she said.

County officials said the expected price of renovating the building was not manipulated to enable the purchase of the Gas Company Tower.

The county’s estimate incorporated a technique called base isolation, which requires lifting the entire building off its foundation and placing flexible “isolators” between the structure and the ground that absorb and dissipate seismic energy from an earthquake.

“Base isolation … is commonly the most expensive technical approach to retrofits and is rarely used except for the very few structures in the area that need immediate occupancy after a major earthquake, such as a hospital, or City Hall,” structural engineer David Funk said in a letter to the Board of Supervisors.

Much less expensive alternatives for the Hahn building include adding shear walls, diagonal bracing, hydraulic pistons and other common solutions that have been used on other historic structures, including the Hall of Justice, built in 1925.

Two structural engineers suggest that the building may not even need any retrofitting because, with its steel frame, it isn’t an ordinary concrete structure.

“The building has a steel-framed gravity system (steel beams supported by steel columns) encased with concrete for fire protection, typical for steel framing of this era,” said structural engineers Nina Mahjoub and Jose Machuca of engineering firm Holmes in a letter to Supervisor Hahn. “This independent steel frame is far more reliable than an equivalent concrete gravity structure of the same vintage.”

“It is our opinion” that building should not fall under the 2015 ordinance and “would not require a mandatory seismic upgrade. Any improvements can be done on a voluntary basis.”

If it is not demolished, the Hahn building would have to be retrofitted to be safer during an earthquake by 2045, according to a September report from the Department of Public Works.

“The Gas Company Tower, in contrast, does not require seismic retrofit to comply with existing codes,” the county said.

Hahn, who said she voted “hell no” against the original decision to move, believes she is in an uphill fight with county staff to keep the Hahn building the home of county government.

“A proposal to get rid of the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration and move to the Gas Company Tower will be probably vigorously defended,” she said. “I’m worried that the train has left the station.”

The post Did L.A. County overstate a $700-million problem? The fight to save a landmark — and taxpayer money appeared first on Los Angeles Times.