President Trump, who recently pardoned a former Latin American leader for his drug-trafficking conviction, is considering direct military action against another, whom he accuses of sending drugs and criminals to the United States.

Latin America is used to interference by its behemoth neighbor. In fact, the U.S. military’s modern history in the region is filled with about-faces, contradictions and missteps.

There were the tamales in Panama that U.S. troops insisted were cocaine. A futile monthslong odyssey through the scrub of Mexico to find a certain former ally turned revolutionary foe. And that doesn’t include the C.I.A.’s adventures in the region or the Iran-contra affair, a political scandal so convoluted that it cannot fit in the confines of this article.

Now, the U.S. military is killing scores of people on vessels in the Caribbean Sea, accusing them of smuggling drugs, as Mr. Trump increases pressure on President Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela.

Here is a look at some other examples of the U.S. military’s efforts at regime change in Latin America.

1898

Cuba

The Spanish-American War in 1898 led to a number of U.S. interventions in Latin America, particularly in Cuba.

The U.S.S. Maine was sent to Havana that January on a stated mission of protecting American citizens. After a mysterious explosion sank the battleship a month later, the United States began a naval blockade of Cuba and went to war with Spain. That campaign expanded to Puerto Rico, and then reached the Pacific to include the Philippines and Guam.

The war ended with the 1898 Treaty of Paris, signed in December, which ceded ownership of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines to the United States. Spain also relinquished control of Cuba.

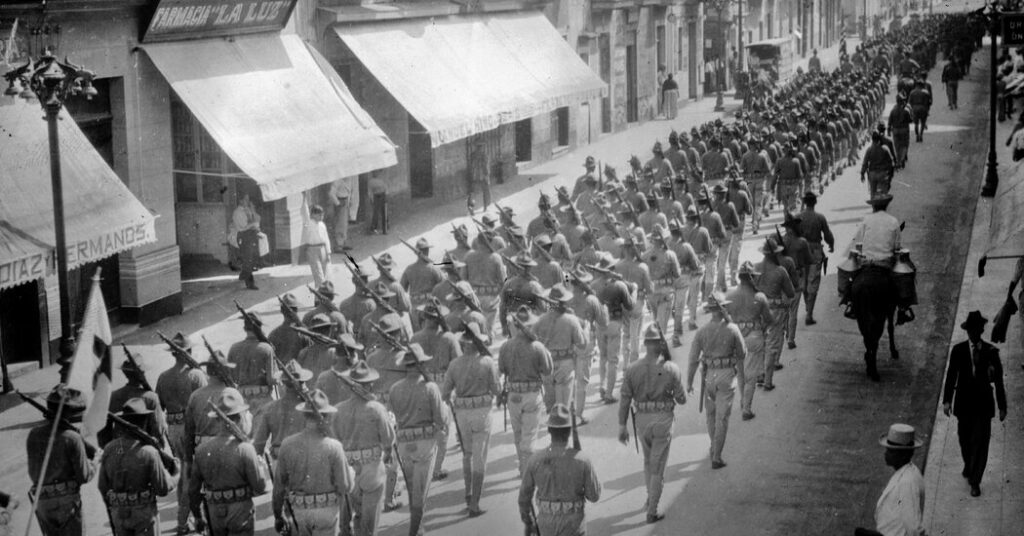

Marines had landed in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in June 1898 and moved swiftly through the island. It was the start of a long period of Marine involvement in conflicts in Central America and the Caribbean, which came to be known as the Banana Wars.

“Before the Second World War, this is what the Marine Corps did,” said Mark F. Cancian, a senior adviser with the Central for Strategic and International Studies and a retired Marine Corps colonel. “Their bread and butter was destabilizing and overthrowing governments in Latin America.”

1912

Nicaragua

Nicaragua was in the middle of a revolt against its right-leaning and pro-American president when Marines landed in the country on a stated mission to preserve U.S. interests. This quickly turned into a direct military intervention and began 21 years of occupation of Nicaragua as part of the Banana Wars.

1914

Mexico

Tensions were high between the United States and Mexico in 1914, as the latter underwent political upheaval fomented by the former. The year before, the United States had worked to overthrow a Mexican president in favor of another who was viewed as more pro-American, leading to a coup d’état, only to turn around and withdraw support for the new president, backing the bandit and revolutionary leader Pancho Villa to depose him.

Then came the I’m-sorry-I’m-not-sorry squabble. The Mexican government arrested nine American sailors in April 1914 for entering an off-limits fuel-loading station in Tampico, on the country’s east coast. Mexico released the sailors, but the United States demanded an apology and a 21-gun salute. Mexico agreed to the apology but not the salute.

President Woodrow Wilson ordered a naval blockade of the Port of Veracruz, to the south. But before that could be carried out, he discovered an arms shipment heading to Mexico in violation of an American arms embargo. The U.S. Navy seized the Port of Veracruz, occupying it for seven months.

1915

Haiti

After President Vilbrun Guillaume Sam of Haiti was assassinated (shortly after ordering the execution of 167 political prisoners), Wilson sent Marines to the country. The stated mission was to restore order and stabilize Haiti’s turbulence, which had been fueled in part by U.S. actions such as the seizure of its gold reserves over debts.

The Marines stayed almost 20 years, finally withdrawing in 1934.

1915

Mexico

Remember Pancho Villa? By 1915, the United States had turned against him and was providing rail transportation for anti-Villa forces. That angered Villa, who started attacking American troops, citizens and their property in northern Mexico and the southwestern United States.

On March 9, 1916, Villa’s troops attacked a U.S. Army post in New Mexico, killing eight soldiers and 10 civilians, wounding eight more people, and stealing horses, mules and machine guns.

Wilson sent U.S. Army troops into Mexico to find Villa “with the single object of capturing him and putting a stop to his forays,” according to a military statement. They searched for almost a year but did not find him, and returned home in 1917. Villa eventually retired and was killed in 1923 in an ambush led by Jesús Salas Barraza, who claimed his motivation was a dispute with Villa over a woman.

The futile American hunt turned Pancho Villa into something of a folk hero in Mexico. “Whenever the U.S. became an arbiter of internal affairs, it skewed the politics,” said Miguel R. Tinker Salas, a professor emeritus of history and Latino studies at Pomona College.

1983

Grenada

The United States accused the government of Grenada of building an airport that would project Soviet power in the region, claiming that its long runway could enable the Soviet Union to land giant transport planes capable of moving weapons.

A political leadership crisis in Grenada that fall eventually led to the execution of its prime minister. The military announced a curfew and said anyone on the streets in violation of the order would be shot on sight.

At dawn on Oct. 25, President Ronald Reagan sent 7,600 troops, including two Army Ranger battalions, the 82nd Airborne, the Marines, Delta commandos and Navy SEALs, supported by American warplanes and Army helicopters. His stated reason was to protect 600 American medical students in the island country.

The U.S. troops made quick work of 1,500 Grenadian soldiers involved in the initial defense of the country, and within a few days most of the resistance was gone. Grenada’s military government was overthrown, and an interim one was installed. On Nov. 3, Reagan announced the mission was successfully completed.

1989

Panama

Gen. Manuel Noriega, the military leader of Panama, had longstanding ties to the C.I.A. and to its director, George H.W. Bush, who would be elected president. From the 1960s to the 1980s, the United States paid General Noriega to help sabotage the left-wing Sandinistas in Nicaragua and the F.M.L.N. revolutionaries in El Salvador. He also worked with the Drug Enforcement Administration to restrict illegal drug shipments — and laundered drug money as a side hustle.

But around 1986, news reports surfaced in the American media about the criminal activities of General Noriega, who was now the military dictator of Panama. Mr. Reagan asked the general to step down; he refused. American courts indicted him on drug-related charges. General Noriega soured on the United States and started asking for and receiving military aid from Cuba, Nicaragua and Libya, which were Soviet-bloc countries.

The general survived attempted coups and a disputed election. On Dec. 15, 1989, Panama’s General Assembly passed a resolution declaring a state of war with the United States.

The next night, four U.S. service members were stopped at a roadblock in Panama; one was shot and killed. Mr. Bush ordered in U.S. troops to remove General Noriega.

And so arrives the story of the tamales.

Shortly after U.S. troops arrived in Panama, in late December 1989, they announced that they had found 50 pounds of cocaine in a guesthouse used by General Noriega. The head of U.S. Southern Command raised the amount found to 110 pounds.

The next month, the Pentagon issued a retraction. A department spokesman told reporters that the department had been supplied with “less than satisfactory” information by troops in Panama. The cocaine, he said, was actually tamales.

“It’s a bonding material,” The Los Angeles Times quoted Maj. Kathy Wood as saying. She added, helpfully, “It’s a substance they use in voodoo rituals.”

1994

Haiti

Sixty years after their first trip to Haiti, the Marines were back, this time with Army troops, after President Bill Clinton ordered the U.S. military to restore to power President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who had been democratically elected and quickly overthrown.

Ten years later, Mr. Aristide was out of favor with Washington and ousted in a coup orchestrated by the United States and France, which had colonized the country.

Helene Cooper is a Pentagon correspondent for The Times. She was previously an editor, diplomatic correspondent and White House correspondent.

The post ‘Voodoo Rituals’ and Banana Wars: U.S. Military Action in Latin America appeared first on New York Times.