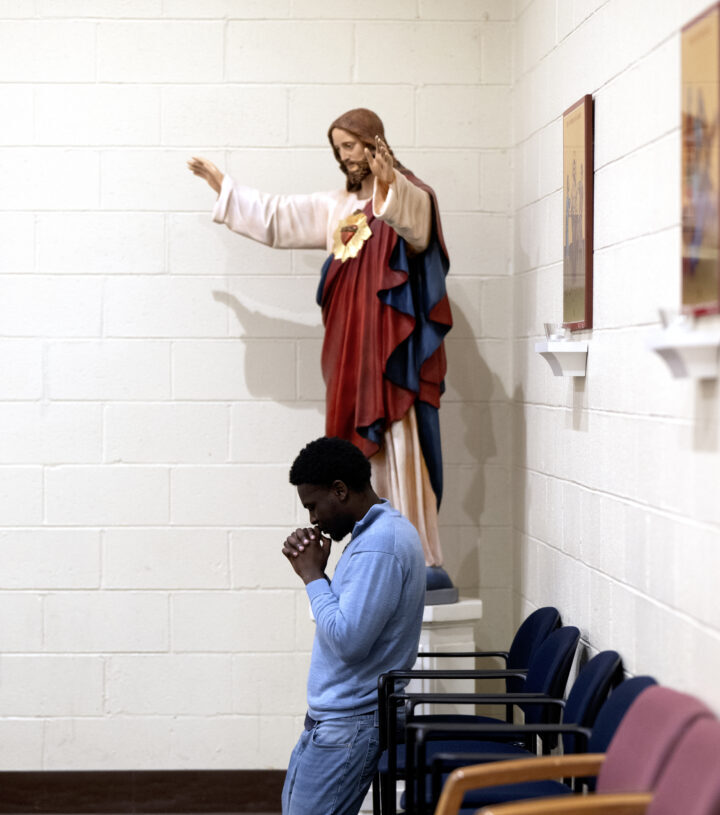

It was a Wednesday night, so Aidan Brant was where he almost always is on Wednesday nights: at Mass. Mondays and Thursdays the University of Maryland sophomore comes for two different Bible studies at the Catholic Student Center. Monday nights he’s there for sacraments class, and he attends a weekend Mass as well.

Brant’s dedication to his new faith might put even the most devout Catholic to shame. But he is not alone among his fellow college students. The Rev. Conrad Murphy, the center’s chaplain, says the number of students who have converted to Catholicism in the past year is higher than it’s been at any time in at least the past 15 years. And weekly Mass attendance this fall has been more than 500, center data shows, which is about double where it has been over the past five years.

Growing up, Brant, 19, went to a nondenominational evangelical church in Clarksburg, Maryland, where services consisted mostly of singing contemporary hymns and a quick sermon. But since he got to the University of Maryland, Brant, a former high school football player, has wanted something more intense — worship services that are mostly prayer and less pop-music-sounding singing, and clear teachings on topics like abortion and gender. Above all, he said he wants to spend as much time as possible close with God.

“There’s nothing more rewarding than chasing God,” Brant said recently as more than 100 fellow Catholic students chatted loudly at a post-Mass dinner of pasta and salad.

Brant’s search reflects a hidden trend religious and spiritual leaders say they are observing among younger Americans: Even as fewer and fewer young people consider themselves religious, a small percentage of young adults are practicing their faiths with unusual avidity. This cohort of people in their early 20s are rejecting both religion-by-habit (just doing whatever your parents did) as well as the secularism, skepticism and agnosticism that grew among their parents’ generations, religious experts say. And the examples of this surge, albeit anecdotal, are visible across faiths — including traditional brick-and-mortar worship of Catholicism, more Jewish college students attending the growing number of Chabad centers, and more esoteric spiritual practices such as Wicca-based full moon rituals and the West African system of divination called Ifa.

“In the past it was more that you went to Mass out of obligation,” said Murphy, the campus chaplain. This generation of Catholic parents, he said, doesn’t expect their children to go — “doesn’t even want them to!”

But despite the religious indifference of their parents, “there’s always a line” at the campus center these days, Murphy wrote in an email. What Murphy says he hears from the students coming through the center’s doors is “a desire for deeper meaning, more authentic community (especially as compared to the online communities they have been exposed to) and a desire for truth.”

Talk of surging interest among young people has taken on a political cast in recent months. Earlier this year, the killing of conservative activist Charlie Kirk, who spoke often of his Christian faith, led to extensive public celebration of Kirk as a martyr whose death would encourage people to deepen their commitment to their faith. President Donald Trump on Thanksgiving seemed to lend credence to this prediction, saying: “more people are praying, churches are coming back.”

New data from the Pew Research Center does not support this idea of a revival.

According to an analysis of 2023-2024 Pew data released Monday, 56 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds identified with any religion, down from 74 percent in 2007. Also among 18- to 24-year-olds, a separate Pew survey this year finds about five times as many people have left Christianity since childhood as have converted to the faith.

“The main thing about young adults is that they are way less religious than older people, full stop,” Gregory Smith, senior associate director of research at Pew, told The Washington Post. “Unless something changes, the demographic patterns in the data suggest the long-term declines in religion will continue.”

Nevertheless, Gallup polls find worship attendance among adults under 30 is up from 19 percent in 2020 to 25 percent this year, and anecdotes abound that a subset of young people is collectively pursuing spirituality in a highly individualistic era.

Christian Smith, a prominent sociologist who runs the Center for the Study of Religion and Society at the University of Notre Dame, says mainstream U.S. polling categories are missing a massive world of what he calls “enchantment” — young people seeking meaning in everything from paganism to magic to books and games about demons.

“The context is that our broader mainstream culture is a dead zone of larger meaning,” Smith said. Commercialism, careerism, technology that makes lofty promises with unclear costs, he says, don’t tell people: “What are we here for? … Humans are constitutionally meaning-seeking, purpose-seeking.”

Eric Doolittle, the chaplain at American University, who oversees the school’s Kay Spiritual Life Center, said all the religious and spiritual groups across campus are seeing more interest and involvement. That, he told The Post, includes the huge international evangelical campus network Cru (originally called Campus Crusade for Christ), humanists and Muslims. “And those who are involved,” he said, “seem to be more heavily involved. Young adults are looking for deep connection points.”

‘Asking hard questions’

Dana Kang, a second-year Master’s student in mechanical engineering and renewable energy at the University of Maryland, grew up in a nonreligious family in Korea. Kang, 24, would sometimes join a friend at a Protestant church but was turned off by things the pastor said that even as a young child she saw as wrong — such as his belief that secular music is a sin, or his sharing of his political views. She visited a Catholic Church during her undergraduate education with a boyfriend, and felt drawn to its fixed worship and firm truths.

“People are looking for a place for refuge amid so much uncertainty, war and political instability,” Kang said at the recent post-Mass pasta dinner. She started conversion classes in August after researching various faiths and listening to a popular YouTuber called Redeemed Zoomer, who gets millions of views for catchy, animated videos explaining aspects of religion.

“Because the Catholic Church is the church Jesus Christ started, the teachings stay consistent over thousands of years, and in this world where everything else changes so quickly that’s one aspect I like. It’s consistent so it feels more real,” Kang said.

Zach Golden grew up going to church but never really connected with Christianity. A Baltimore high-schooler during covid lockdowns, he started meditating out of boredom and an affinity for “Star Wars,” which draws heavily from Taoism.

Now a senior at American University, Golden meditates and practices Qigong. Earlier this year he launched a program that combines sports and spirituality, exploring topics like how trauma impacts athletics and the way people experience their bodies and movement.

“We see all these things and we’re so numb. Our generation — we’re the test dummies for the internet and social media,” he said. “That’s what’s leading to what I guess is a spiritual revolution.”

On a recent Monday night, in a modest, industrial-style space on trendy U Street in Northwest Washington about 50 young adults, mostly women, gathered for the first of two “Core” classes run by Passion City, a popular evangelical megachurch based in Atlanta. Passion City opened a D.C. branch in 2018 and has attracted multiple young, high-level political operatives, including White House spokeswoman Karoline Leavitt, who posted from there on Instagram.

The goal of the course was to ground newcomers in what teachers described as the core truths of Christianity — Jesus as fully human and fully God, the divinity of the holy spirit and Jesus’ death as a way to reconnect sinning Christians to God. “If you’re in a church that preaches: ‘Here’s five easy steps to be your best self,” something is wrong,” Jacob Harkey, formation director of Passion City in D.C., told the class.

“A lot of people are maybe going deeper than they ever have. It’s like ‘Hey, I grew up culturally Christian, but I’m actually engaging with what I believe for the first time and asking hard questions,’” Harkey said later.

One of those people asking the hard questions is Gibson Murray, 23, a software engineer who said he had dabbled in atheism and nihilism until anxiety and depression made him desperate to explore Christianity more seriously. Murray got even more involved in study and attending Passion City — both classes and volunteering at Sunday services — and says he now feels healthy and at peace.

“We are raised in this world where information is everything and yet it could be meaningless and false. … In a world of fake news, what is real?” said Murray. “People are turning to a book that has been unchanged for 2,000 years and that’s where we are finding peace and purpose and truth.”

Scott Clement contributed to this report.

The post Religious leaders say they’re observing a hidden trend among younger Americans appeared first on Washington Post.