Philip Hamburger teaches at Columbia Law School and is chief executive officer of the New Civil Liberties Alliance. This column is adapted from his research paper “No Rights for Deportees?”

In November 1785, three individuals dressed in attire described as “Asiatic” arrived by ship in Hampton, Virginia. Curiously, the two men and a woman had papers in Hebrew but insisted they were Moors. Their exact identity was, and still is, unknown. Regardless, they were called “Algerians” and evidently were from the Barbary States.

Today, when the U.S. government tries to remove foreigners, it’s useful to recall the experience of the 1785 visitors to understand whether deportees have constitutional rights.

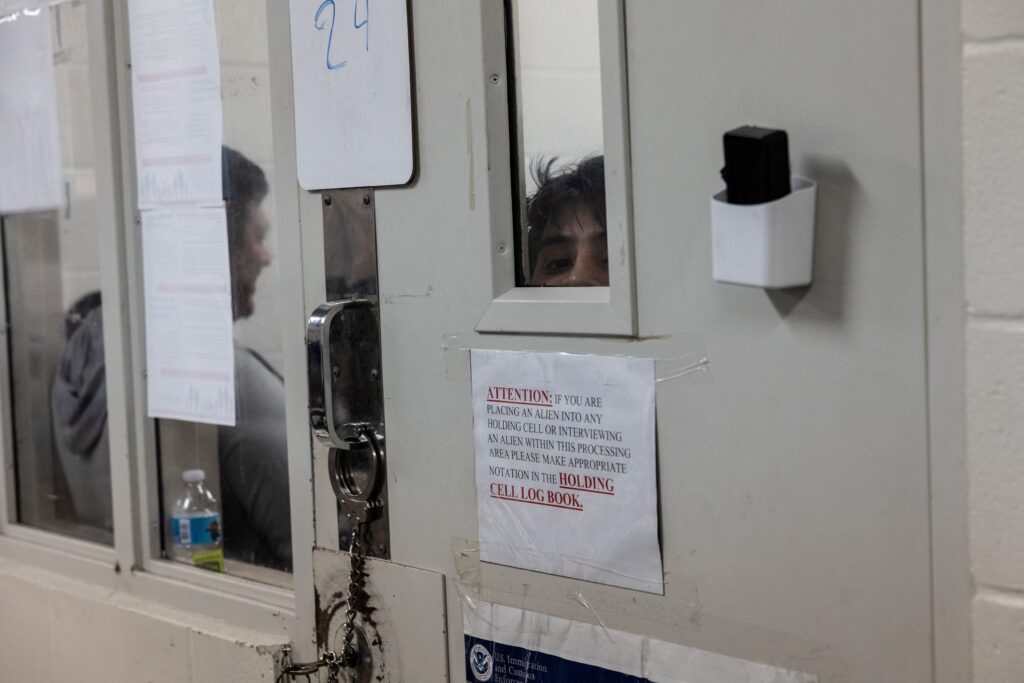

The current debate centers on suits brought by individuals such as Mahmoud Khalil, a former Columbia University student who is arguing that he was designated for deportation in violation of his speech and due process rights. Although the United States is celebrated for offering equal rights to all people present in the country, Supreme Court doctrine has largely denied rights to deportees. This “immigration exceptionalism” looks inconsistent and unprincipled. So it’s important to consider whether the complaining deportees have a point.

Here, the events of 1785 are illuminating. While piracy was an ongoing problem, the Barbary States were not clearly at war with United States, which means that the three “Algerians” couldn’t be treated as enemy aliens. But these individuals provoked suspicion because of recent attacks on American vessels. Virginia Gov. Patrick Henry and his Governor’s Council felt they had to take action.

Henry and the council initially acted on their own. Then, after wondering whether they needed statutory authorization, they asked the state legislature to authorize them to detain and search the foreigners. The statute, prepared by a committee headed by James Madison, permitted the governor to detain, search and deport “all suspicious” foreigners — not only if their nations were at war with the United States but also if Congress merely apprehended “hostile designs” against the United States. The statute had no provision for judicial review.

Henry, however, chose not to wait. After about two weeks, while the bill was still in committee, he and his council simply ordered the three searched and deported. Apparently, upon reconsideration, Henry assumed he could act within the scope of his executive power.

The fate of the “Algerians” illustrates the principle of protection and its role in demarcating who enjoys constitutional rights. In the law of nations, the protection of the law was said to be reciprocal with allegiance, meaning an intent to obey the law. Both protection and allegiance depended on mutual consent.

Thus, when foreigners came to a country with both an intent to obey the law and the nation’s consent, they enjoyed rights under its laws. The early American states, at least tacitly, consented to the arrival of law-abiding visitors, and those from the Barbary States therefore seemed to have claims to constitutional rights in Virginia. But once Virginia decided to deport the three arrivals, they no longer had the state’s consent and thus were no longer were within the protection of its law. They then could be detained, searched and deported without constitutional objections.

Put another way, prior to a claim of constitutional rights, there is always a preliminary question about the domain of the legal system. In a multinational world, there has to be a limit on the domain of any one country’s law.

The denial of rights to deportees is therefore not inconsistent, unprincipled or unconstitutional. As illustrated by the story of the “Algerians,” constitutional rights, since their beginnings in the United States, have always been subject to a caveat about domain. When visiting foreigners were excluded or told to leave, the limits of the principle of protection meant they no longer enjoyed rights under our legal system.

Of course, deportees should not be abused. Indeed, the United States and its officials remain subject to international law and American criminal law. And Congress, if it wishes, can always bar deportation on the basis of speech. But unless Congress accorded the protection of law to deportees, they traditionally did not enjoy rights in American courts.

Although the Supreme Court has largely forgotten the principle of protection, the court’s doctrines still largely reflect the lines drawn by this principle. That is fortunate — most obviously for security, but also for other reasons. The nation can have a relatively open door only if the executive retains much discretion, within statutory bounds, to make decisions about deportation. So, judicial decisions complicating or interfering with that executive discretion are apt to lead to tightened limits on immigration. The principle of protection is essential both for security and for generosity in immigration.

The three “Algerians,” whoever they really were, are a reminder of our law’s limited domain.

The post How three 1785 Barbary Coast deportees illuminate the law’s limits appeared first on Washington Post.