JOSHUA BARONE

High-Concept Operas and Incandescent Performances

Few art forms are as burdened by canons as classical music and opera. That, perhaps, is why I love to be surprised: to come across premieres and fresh interpretations that upend my expectations and open my mind to new possibilities. When I think about the past year, those are the moments that stuck with me most. Here are 10 of them, in chronological order.

Sound On

This series at the New York Philharmonic is like a Criterion Collection for music: You may not be familiar with everything you see, but you can expect it to be well curated and special. In January the orchestra paid tribute to Pierre Boulez’s famous rug concerts from the 1970s, reviving a program that included rarities like Boulez’s “Pli Selon Pli,” with the radiant soprano Jana McIntyre in her Philharmonic debut. And in October, Sound On offered the American premiere of Chaya Czernowin’s “Unforeseen dusk: bones into wings,” a work that stretches the potential of the human voice and practically immerses its listeners in waves of color, texture and sensation. (Read about Boulez’s centennial.)

Ted Huffman

What a year for Ted Huffman. At the Dutch National Opera in March, he premiered “We Are the Lucky Ones,” a shattering portrait of a generation based on interviews with people born in the 1940s. He directed the show and wrote the libretto with Nina Segal; Philip Venables, his frequent collaborator, composed the dreamy, genre-hopping score. Then at the Aix-en-Provence Festival in the summer, he unveiled a new version of Benjamin Britten’s “Billy Budd,” an erotic live wire trimmed to one act, scaled to chamber opera size and featuring seductively atmospheric music by Oliver Leith. Look forward to more from Huffman at the Aix festival: He was named its artistic leader in October. (Read our reviews of “We Are the Lucky Ones” and “Billy Budd.”)

Leos Janacek

Janacek’s operas are some of the most dramatically intense out there: Vivid in their storytelling and devoid of bloat, they demand a visceral response. That is as true for Janacek’s flops as it is for his finest efforts. Both ends of that spectrum were on display in Germany this spring, with new productions of “The Excursions of Mr. Broucek” at the Berlin State Opera and “Kat’a Kabanova” at the Bavarian State Opera. “Excursions” is often dismissed as a problem opera with wonderful music; the director Robert Carsen proved that while it isn’t perfect, it can work. And the breathless “Kat’a” was all the more desperate and heartbreaking in the soprano Corinne Winters’s performance. (Read about Janacek’s operas.)

‘Hotel Metamorphosis’

At the Salzburg Whitsun Festival in June, the director Barrie Kosky brought back the old-fashioned pasticcio: an operatic form, similar to the jukebox musical, that tells an original story with arias from other shows. He adapted tales from Ovid into “Hotel Metamorphosis,” an often overwhelmingly beautiful quilt stitched from music by Vivaldi. The material brought out creativity and intelligence from Kosky, and incandescent singing from Cecilia Bartoli, Lea Desandre and Philippe Jaroussky. In the pit, Gianluca Capuano led Les Musiciens du Prince-Monaco, a period ensemble whose players seemed to embody the score, channeling it with their every movement. (Read our profile of Bartoli.)

‘The Comet/Poppea’

It takes a high-concept production to persuasively collide Monteverdi’s 17th-century “L’Incoronazione di Poppea” and George Lewis’s new opera “The Comet.” And that’s what the director Yuval Sharon delivered in the ambitious and intricate “The Comet/Poppea,” which came to Lincoln Center in June. The show placed two operas, one a Baroque take on ancient Rome, the other a modern adaptation of an apocalyptic short story by W.E.B. Du Bois, on a single, continuously rotating set. What could have been a gimmick was instead a dialogue that, in Sharon fashion, had by the end a wise and moving statement to make about the power of opera itself. (Read about “The Comet/Poppea.”)

Gustavo Dudamel’s Corigliano

The 2025-26 season is Gustavo Dudamel’s last at the Los Angeles Philharmonic and something of a soft launch for his tenure as music and artistic director of the New York Philharmonic, which officially begins next fall. Admirably, he uses his almost unmatched celebrity among conductors to champion contemporary music. And when he visited his new orchestra for a pair of programs in September, he offered a galvanic interpretation of John Corigliano’s First Symphony: an AIDS memorial in music that, written at the height of the epidemic, teems with rage and elegiac anguish. It is a piece with something important to say, and Dudamel was just the person to say it. (Read our review of the first program.)

‘One Battle After Another’

Jonny Greenwood’s soundtracks for movies by Paul Thomas Anderson could stand alone as sophisticated concert works. Sometimes, Greenwood’s scores don’t illustrate scenes and characters so much as riff on them, resulting in a kind of conversation across media between two fascinating artists, him and Anderson. “One Battle After Another,” released in late September, is one of their finest collaborations yet. Greenwood evokes the film’s anxious mood and episodes of suspense in a soundtrack of jittery tension and unpredictability, with moments of humor and high drama. (Read our review of “One Battle After Another.”)

‘11,000 Strings’

There was a sensational quality to Georg Friedrich Haas’s “11,000 Strings,” which had its North American premiere at the Park Avenue Armory this fall. Inside the vast drill hall, 50 microtuned pianos and the 25 instrumentalists of Klangforum Wien surrounded the audience, offering a bit of spectacle that belied a profound and brilliantly crafted sensory experience. At times, the players behaved with the consonance of a hive and the dissonance of an explosive cataclysm; throughout, the sound was stunning, a testament to the power of music on an immense scale. (Read about “11,000 Strings.”)

Rosalía

Near the end of October Rosalía dropped her single “Berghain.” More than an immediate hit, it was a rich topic for discussion among fans of classical and pop music alike: What genre was it? Recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra and freely borrowing from Vivaldi and opera in its style, it signaled rare ambition, eclecticism and sheer resources. The rest of the album, “Lux,” continued in the vein of “Berghain.” It may not have been successful as a work of classical music or opera, but that’s not what it was. She is a pop artist who made a pop album, and along the way, praise be, she got people talking about all these art forms. (Read about “Lux” and classical music.)

‘The Monkey King’

You couldn’t ask for a better world premiere than “The Monkey King” at San Francisco Opera in November. It was a special case of opera firing on all cylinders: in David Henry Hwang’s libretto, based on the Chinese classic “Journey to the West”; in Huang Ruo’s thrillingly propulsive score; in excellent performances throughout the cast, chorus and orchestra; and, above all, in Diane Paulus’s silky production, which heavily featured the sublime puppetry of Basil Twist. With a sold-out run, it was also a hit at the box office. If that doesn’t speak to the vitality of opera, I don’t know what does. (Read our review of “The Monkey King.”)

corinna da fonseca-wollheim

A Season for the Strange and Luminous

Classical music and opera can sometimes seem to trade in prettiness, but the performances that stayed with me this year were the ones that expanded the spectrum of sound, finding expressive gold in the gritty, the luminous and the bracingly strange. Across the field, artists brought a sense of adventure to performances of old and new music, and reminded us that nothing can replace the immersive wonder of hearing music unfold in real space.

Barbara Hannigan in John Zorn’s ‘Jumalattaret’

There are performances that impress you with sheer difficulty, and others whose strangeness keeps you at arm’s length. In Barbara Hannigan’s account of John Zorn’s nearly unsingable “Jumalattaret,” virtuosity seemed to open a portal to mystery and wonder. In this 25-minute whirlwind including birdlike tremors, throat-singing and airborne runs, Hannigan redefined what a human voice might want to do. Her exchanges with pianist Bertrand Chamayou turned the Finnish-mythology cycle into ritual theater. It was an overwhelming reminder of Hannigan’s singular artistry as a soprano as she prepares to spend more of her career as a conductor. (Read our review.)

Christopher Cerrone’s ‘In a Grove’

Each January, the iconoclastic Prototype Festival starts off the year with new variations on its punk-noir aesthetic for opera. This year’s highlight was Christopher Cerrone and Stephanie Fleischmann’s “In a Grove,” a taut, time-bending meditation on truth and violence. Presented in an immersive minimalist staging at La MaMa, the opera reimagined Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s short story as a frontier ghost story set in a postapocalyptic forest. Cerrone’s score, flickering with subtle electronic effects, moved like a single surging organism that conjured a mood of psychological unrest. The cast, led by a dangerously magnetic John Brancy, turned each testimony into another shard of an exquisitely fractured puzzle. (Read our review.)

Leif Ove Andsnes

With Grieg and Chopin anchoring the program, the thoughtful pianist Leif Ove Andsnes’s solo recital at Carnegie Hall seemed to promise an evening of familiar sounds brought to life with his customary crystalline detail and unshowy depth. But what lingered was the unexpectedly moving discovery at its center: the 30-minute Piano Sonata No. 29 by Geirr Tveitt, an early 20th-century Norwegian composer who worked in near-reclusion in the Hardanger region. This was my first introduction to the voice of a luminous outlier and a work that alchemizes modernist experimentation and folk memory into shimmering, spectral soundscapes.

Patricia Kopatchinskaja in Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto

In her long-awaited New York Philharmonic debut, the maverick violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja brought the intensity of a method actor to Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto, playing with full-body commitment and sounds that included expressive scratches, whispers and wolf tones. What may live longest in the memory of the electrified audience was Kopatchinskaja’s encore, Jorge Sánchez-Chiong’s “Crin,” a 90 second anarchist tour-de-force of vocal and violinistic virtuosity. (Read our review.)

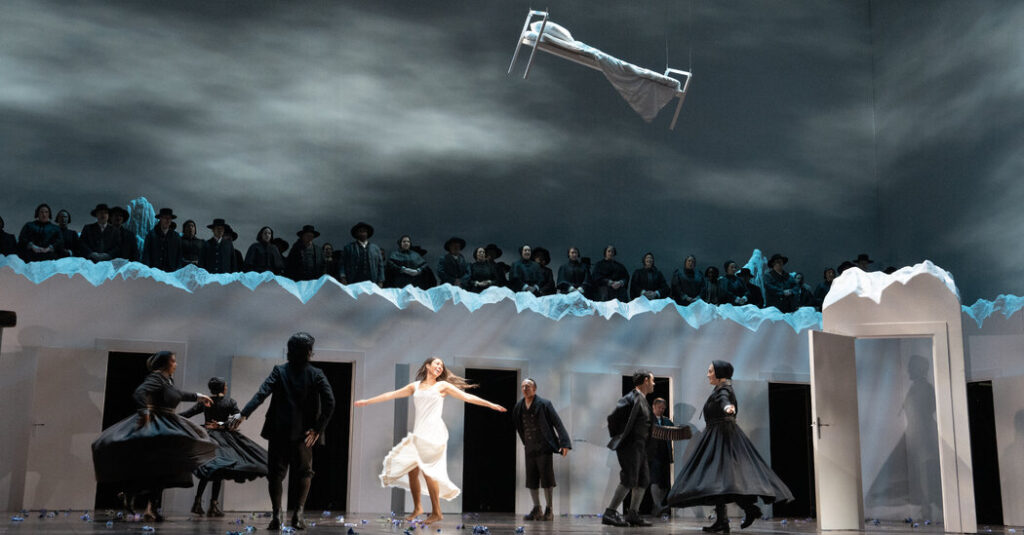

‘La Sonnambula’

Done well, bel canto opera offers some of the most unapologetic treats in the classical repertoire. Rolando Villazón’s new staging of “La Sonnambula” for the Metropolitan Opera, restoring Bellini’s pastoral fantasy to an Alpine world of superstition, repression and wild beauty, delivered, led by a dream duo. Nadine Sierra sang her playful, volatile Amina with seemingly effortless finesse opposite the sensational young Basque tenor Xabier Anduaga. With its revival of Donizetti’s “La Fille du Régiment,” the Met followed up with another bel canto winner, this one carried by the irrepressible charm and flawless coloratura of the soprano Erin Morley. There were more fizzy crescendos and goofy gags earlier in the year as Rossini’s “The Barber of Seville” returned with a wonderfully Machiavellian Alexander Vinogradov as the scheming Don Basilio. (Read our reviews of “Sonnambula” and of “Fille.”)

The Gewandhaus Orchestra’s Shostakovich

Shostakovich’s music was seemingly everywhere this year, 50 years after his death, in programs showcasing the dazzling stylistic breadth of his catalog. Among his fiercest champions is the conductor Andris Nelsons, who led two illuminating Shostakovich programs with the Boston Symphony at Carnegie Hall and later ignited the Gewandhaus Orchestra in Leipzig on the opening night of a Shostakovich Festival. The genial sparkle of the Festive Overture and the clean-lined lyricism of the Second Piano Concerto, with a searching Daniil Trifonov, set up a shattering account of the Fourth Symphony. Clarity, weight and ferocity converged in a performance that captured Shostakovich at his most buoyant, embattled and enigmatic. (Read our review of the Gewandhaus program.)

‘Salome’

The shortest opera at the Met his year was also the most potent: Strauss’s “Salome.” Some 90 minutes after the first downbeat I stumbled out shaken but invigorated. Claus Guth’s staging, haunted by six young doubles of its heroine, reframed Strauss’s biblical shocker as a study in post-traumatic stress. Elza van den Heever’s cool, luminous Salome led a superb cast. In the pit, Yannick Nézet-Séguin whipped up a performance of simmering force — a welcome reminder that opera is capable of delivering bone-rattling catharsis. (Read our review of “Salome”)

Pene Pati

The Samoan-born tenor Pene Pati is a rising star on opera stages, with a stadium-size voice and charisma to match. But his New York recital debut, in the intimate Board of Officers Room at the Park Avenue Armory, offered an opportunity to hear him up close. With an attentive Ronny Michael Greenberg at the piano, Pati delivered pliant lyricism, dramatic acuity and forensic attention to language in French and English songs, revealing a chamber musician worth watching. (Read our review of the recital.)

Boulez’s ‘Rituel’

One of the fall’s unmissable events turned out to be a tribute to Pierre Boulez, a modernist often branded as forbidding. Yet in “Rituel,” the culminating work of the New York Philharmonic’s centenary homage, the austere logic of his compositional technique resulted in an evening of extravagantly sensual immersion, heightened by the sculptural interventions of dancers choreographed by Benjamin Millepied. With the orchestra divided into eight satellite ensembles throughout the hall, Esa-Pekka Salonen unleashed waves of tolling sonorities and cavernous, breathing silences. (Read our review of “Rituel” here.)

Poiesis Quartet

I heard this vibrant young ensemble mid liftoff, fresh from its first-prize win at the Banff International String Quartet Competition and just before it picked up Chamber Music America’s Cleveland Quartet Award. At Caramoor, its concert included two brilliantly idiomatic quartets by Kevin Lau and a burnished, deeply felt account of Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson’s Quartet No. 1, “Calvary,” prefaced by the group’s four-violin arrangement of the spiritual that inspired it — a casual, telling glimpse of these players’ multifaceted artistry.

Joshua Barone is an editor for The Times covering classical music and dance. He also writes criticism about classical music and opera.

The post Best Classical Performances of 2025 appeared first on New York Times.