How do people used to basic freedoms acquiesce to regimes of domination? When government authorities use the formidable violence at their disposal, it’s no wonder that citizens obey. More surprising are the broad patterns of submission by people who suffer no direct threats, and yet they get used to cooperating with a brutal government.

I see it most clearly in higher education, as universities and leaders that once adopted a posture of firm independence now increasingly seem to want to toe the line, even taking out a full-page ad in the Wall Street Journal to announce their appetite for policies that would please those in power. It’s not just college campuses, though. That short-sighted shift toward accommodation is playing out across the country, in one institution after another.

It’s remarkable what we have gotten used to in just several months: a “secretary of War” who thinks it is legal to execute people in international waters because they might have drugs in their boats; federalized National Guard troops on the streets of major American cities; criminal investigations of the president’s political enemies; calls for the death penalty for members of Congress who remind soldiers of their responsibility to the Constitution.

Perhaps nothing, though, is as striking as the abduction and imprisonment of law-abiding residents doing exactly what was expected of them: going to work, to school or to pick up their children at day care. Take Ali Faqirzada, a student at Bard College. Having worked with Americans in Afghanistan, he fled for his life when the Taliban came to power. He has followed every rule, yet when he showed up at an asylum hearing this fall, immigration agents placed him in handcuffs. He’s been behind bars since October, and after the recent attack on National Guard troops in Washington, his case is more challenging than ever.

Any Lucia López Belloza was heading home to Texas from college for Thanksgiving, but since her mother brought her to the U.S. without papers at age 7, immigration agents lay in wait for her at the Boston airport. They shackled her and shipped her to Honduras, acting, they said, on a 10-year-old deportation order. Belloza is now 19 and was studying business at Babson College. A spokesperson reminded the public that Immigration and Customs Enforcement “is committed to prioritizing public safety.”

Specific stories can spark outrage, but when these are multiplied by the thousands, outrage seems to bleed into acquiescence and then cooperation. Several months ago, one heard often “this is not who we are” as a nation. Even that mild rebuke has now fallen out of rotation. Do we now believe this is who we really are?

Throughout history and around the world, to stay alive or out of prison, or sometimes just to stay in official favor, many people have always found ways to adapt to repressive regimes. Professors have sworn oaths of allegiance, schools have adopted racist curricula and businesses have scuttled the social policies they once boasted about. People have informed on folks down the street. Leaders of institutions that curry favor by betraying their values often say they are doing what they must to protect their constituencies — be they students, clients, employees or investors.

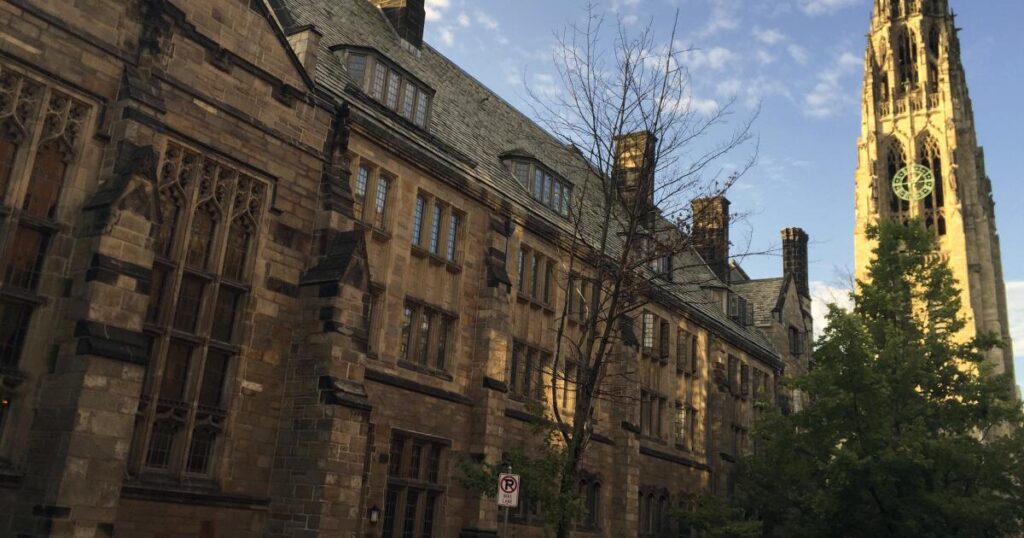

That’s the story that many in higher education are now telling themselves. Regarding the Trump administration’s crackdown, a Yale political theorist was recently quoted in the Wall Street Journal as defending his institution’s silence. “We’re under no obligation to get involved,” Steven Smith said, according to the Journal. “Self-preservation is a noble goal.” At a recent meeting of higher education leaders I attended, someone declared that the policy of their school is simply not to stand out from what others are doing. They said it without shame, and no one expressed shock or outrage. The effort to make higher ed “neutral” has devolved into triumphant obsequiousness.

As many examples as history provides of people going along to get along, however, it also provides many examples of people finding a different path. Today communities from Charlotte, N.C., to Chicago, from San Francisco to New York are “blowing the whistle” on abuses of power by federal agents. Tired of seeing ICE swooping into day care centers or churches, car washes and Home Depots, people across the U.S. are alerting their neighbors when masked authorities in unmarked cars attack their cities and towns. These ordinary citizens are exercising their civic responsibility to slow down the machinery of authoritarianism. They are practicing freedom by alerting neighbors to danger, calling attention to patterns of abuse and showing compassion to the persecuted. Their refusal to get used to authoritarianism should be a lesson to all of us.

America’s colleges and universities can do it too. We can refuse to let the government and its billionaire allies tell us what or whom to teach. We can practice solidarity, coming to one another’s defense instead of hiding our heads in the sand and hoping the storm will pass. And we can continue to educate students to think for themselves.

What kind of country will we turn out to be? The choices we make now will determine the answer. As Abraham Lincoln put it: “If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher.” Obsequiousness and collaboration spread like viruses to weaken our republic, but the choice to support one another and defend our institutions strengthens it. We have been and can again be a country that refuses to get used to authoritarianism. We can choose instead to work with our neighbors, co-workers and fellow citizens to build our more perfect union.

Michael S. Roth, president of Wesleyan University, is the author of “Safe Enough Spaces: A Pragmatist’s Approach to Inclusion, Free Speech, and Political Correctness on College Campuses” and “The Student: A Short History.”

The post Americans still have a choice whether to let the nation turn authoritarian appeared first on Los Angeles Times.