This past June, Ashley Voss-Barnes received a court summons in the mail.

PrairieStar Health Center, a nonprofit community health center in south-central Kansas, was suing her for $675 and her wife for $732 in unpaid medical bills. Voss-Barnes knew the clinic received federal funding to make preventive health care accessible in a region where many families, including her own, needed financial help.

She didn’t understand what led to the lawsuit. She and her wife had a blended family of five kids that cost a lot to keep healthy. As a result, years ago, the couple had asked PrairieStar if they could set up an ongoing payment plan to automatically take money from their checking accounts multiple times a month. Voss-Barnes would later state in a court filing that PrairieStar never informed her those payments were not enough to cover her bills and keep her out of collections.

“If I have something due, then I will try to pay it,” she said to ProPublica. “It came out of nowhere.”

Voss-Barnes, a nurse who feels confident navigating the health care system, wanted to push back. She reached out to a local lawyer to see if he could represent them, but he said the debt was too small to be worth it. So she represented herself, filing a letter in court objecting to the lawsuit and asking to continue the existing payment plan.

Eventually, Voss-Barnes and her wife agreed to set up new payment plans with the collections agency for the debt, to avoid having the money taken directly from their paychecks through wage garnishment. To their dismay, they owed hundreds more in interest, court costs and lawyer fees as a result of PrairieStar’s decision to sue.

They worry about PrairieStar suing them again. “I know we’re not the only ones this has happened to,” Voss-Barnes said.

The lawsuits against the two women are among at least 1,000 that PrairieStar has filed against patients since 2020 for unpaid medical bills, according to a ProPublica analysis of state court records over that period. Many patients PrairieStar sued were uninsured and made so little money they qualified for discounted care, a former patient accounts employee told ProPublica.

Community health centers like PrairieStar Health, also known as federally qualified health centers, were created to serve as medical safety nets for people who struggle to afford primary care. They were established during the Civil Rights Movement-era “War on Poverty,” when federal officials realized that low-income Americans, overwhelmed by long drives and crowded hospitals, were forgoing medical attention. The health centers receive federal grants in exchange for serving patients regardless of their ability to pay, increasing access across large swaths of the country.

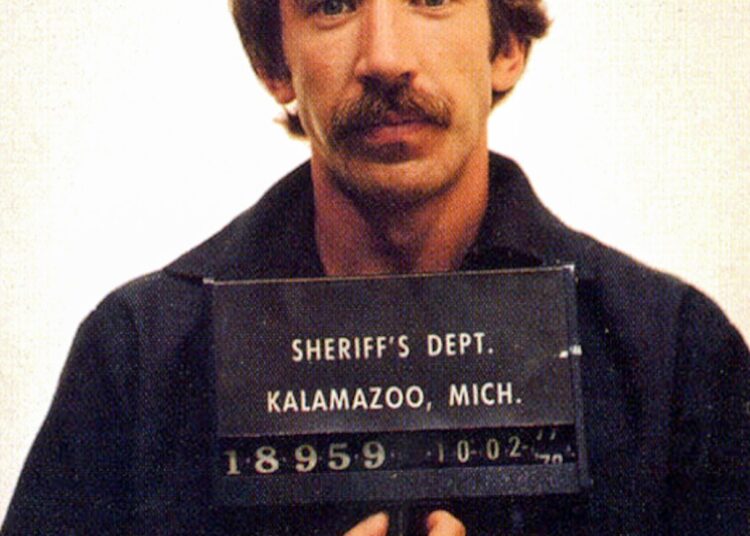

But ProPublica found that several of these health centers are suing patients and garnishing their paychecks — which experts say contradicts their mission. We identified two other centers in Kansas, plus one in rural Virginia and one in Kalamazoo, Michigan, that consistently filed lawsuits against patients since at least 2020. Our search, which was not exhaustive, focused on states and counties where court records are publicly accessible online. We also reviewed documents from a municipality in Alaska and a county in California that run community health centers, which showed they use outside debt collectors to pursue what patients owe.

Leaders of five community health centers, including PrairieStar, told ProPublica they send patients to collections or file lawsuits against them as a last resort, after sending statements and offering payment plans. Three pointed to the financial instability that community health centers face as a reason to pursue patient debt. All five stressed that they did not turn away patients who could not afford medical care, citing a goal to make health care accessible.

In response to questions from ProPublica, PrairieStar CEO Bryant Anderson said that the health center faces “a perfect storm” caring for patients while also dealing with higher costs and unstable funding. “With all the challenges PrairieStar faces to maintain access to care for the uninsured and the underinsured, having someone imply that we don’t fulfill our mission is certainly rubbing salt in the wounds,” he wrote in an email.

Anderson said PrairieStar generally tries six times to communicate with patients before sending them to collections. He also said every patient is given the option to apply for sliding-scale discounts based on income and about a third choose not to provide that information.

Other health center leaders also explained their decision to pursue patient debt through lawsuits, in response to questions from ProPublica. “We understand that sending accounts to collections can seem at odds with that mission, and it’s not a decision we take lightly,” said Renee Hively, the CEO of CareArc, a community health center in Kansas. CareArc has appeared in local news for pursuing one patient’s medical bill through a lawsuit and wage garnishments for more than 12 years, contributing to her being unable to afford basic utilities. (CareArc did not respond to a request for comment about that particular case.)

A spokesperson for the department that oversees community health centers in Monterey County, California, told ProPublica that most unpaid bills it sends to collections “involve small amounts that do not justify the cost of initiating legal proceedings.” As a result, none of its patients have been sued since 2019. If the health centers ever stopped sending patients to collections, the spokesperson said, the financial effect would be “minimal.”

Most of the public attention on medical debt and related lawsuits has been focused on hospitals, especially nonprofit hospitals that receive tax breaks in order to make care more affordable. Hospitals must provide emergency care regardless of whether the patient can afford it but are not required to provide primary care like checkups or routine screenings. Nonprofit hospitals are required by federal law to check whether patients qualify for financial help before suing them or garnishing their wages.

Community health centers, on the other hand, must make “every reasonable effort” to collect money from patients before writing it off, according to federal law.

Though experts and leaders of other health centers say the centers have ample freedom to decide what “reasonable” means — and whether to pursue debt through collections agencies and the courts — Anderson said the manner in which PrairieStar collects debts is mandated by the law.

He also said that ProPublica may be trying to “induce” other health centers to violate federal law by reporting and writing this story. “Your messaging would therefore be dangerous and intimate that such health centers were not required to make ‘every reasonable effort to secure payments’ for their services,” he wrote.

But experts on community health center finances said that federal law does not require the centers to send patients to collections. “There’s no law that says you have to garnish wages or that you have to go after someone through collections,” said Ray Jorgensen, a health care billing consultant who said he has worked with hundreds of community health centers over about 30 years. “I would say that’s an anomaly. That’s not the norm.”

Anderson did not answer specific questions about PrairieStar’s lawsuits or wage garnishments. He repeatedly said that ProPublica did “not have all the facts” and that the story would be “potentially defamatory,” but he did not clarify what he felt was missing or inaccurate. Nor did he respond directly to questions about Voss-Barnes’ experience, even though she and her wife signed privacy waivers allowing him to do so. Voss-Barnes said that he reached out to her directly, telling her that everyone in their Kansas city would know that she had failed to pay her medical bills if she moved forward with the article. (He did not respond when asked about that outreach.) He did tell ProPublica that he personally contacted both a former employee and another patient who ProPublica had asked him about. The patient stopped responding to ProPublica.

Medical debt experts said they were surprised and horrified to hear that community health centers were using lawsuits and third-party debt collectors to recover money from patients, given their intended purpose of providing care to people who have no other options. Under federal law, community health centers must provide discounted care on a sliding scale for patients who make at or below 200% of the federal poverty guideline, an amount that varies based on family size and household income. A family of four must make under $64,300 to receive a discount. Medical debt disproportionately burdens Black, Hispanic, low-income and uninsured patients — groups more likely to use community health centers for affordable care.

“Patients who have been sued because of medical debt are likely to avoid care in the future,” said Miriam Straus, policy adviser for Community Catalyst, a health advocacy group. “These collection activities seem to violate at least the spirit of the requirement to provide health services available to all.”

On Virginia’s Eastern Shore, a narrow peninsula bordered by the Atlantic and the Chesapeake Bay, getting sued by the community health care center is a regular occurrence. Over the last decade, Eastern Shore Rural Health filed more than 7,000 lawsuits for unpaid medical bills in two counties where 45,000 people live.

It sued one couple for $59 in January 2024, an amount that ballooned by more than 600% within months due to interest, court costs and lawyer fees. Court records show money regularly garnished from people working in the low-wage industries that abound on the Eastern Shore, including poultry processing and retail.

On an August morning in Accomack County’s civil court, Eastern Shore Rural Health accounted for most of the cases on the judge’s docket. One man who showed up to court told ProPublica that the visit potentially cost him hundreds of dollars because he missed out on lucrative hours harvesting oysters and clams. He only spoke Spanish and the court did not make a translator available; the judge told him to return for another hearing in the fall. Most people didn’t show up to court at all, meaning the health center won by default.

ProPublica did not find any other community health centers in Virginia consistently suing patients for unpaid bills in the court records.

Eastern Shore Rural Health began using lawsuits to collect medical debt about 20 years ago after conversations about “maximizing our revenue,” according to Kandy Bruno, the organization’s chief financial officer. A local company called Bay Area Receivables handles its collections and takes 30% to 40% of what it recovers from patients through the court. The minimum amount that Eastern Shore sends to collections is $25, Bruno said.

Bruno said Eastern Shore sends patients to collections when it has exhausted other options, including sending out letters, offering interest-fee payment plans and helping fill out Medicaid applications. “We should never have to send anyone to collections,” she said. “It should be 100% avoidable.” She also said the number of lawsuits the company had filed in a decade was not very high compared to the 32,400 patients seen there last year.

Patients are never refused health care, no matter how much they owe, she said.

Virginia recently passed a law that experts say would stop at least some of Eastern Shore Rural Health’s debt collection practices starting next summer. The law prohibits large medical providers from garnishing wages of patients who qualify for financial assistance.

Bruno said she hasn’t yet looked into how the Virginia law would affect the health center or its patients on the sliding scale. “We will absolutely comply with and make adjustments to comply with the letter of the new law,” she said.

The health center is the main option for preventive care on the peninsula; otherwise, people have to make the long drive up to Maryland or pay tolls, often totaling more than $20, to cross the bridge over the Chesapeake Bay. More than 70% of people who live on the Eastern Shore see doctors at the health center, including higher-income people with private insurance through their jobs, Bruno said.

That means some of the patients, she said, make enough to “take responsibility for their care.” But the health center does not track what percentage of patients sent to collections receive financial assistance or make so little that their checks legally cannot be garnished.

Brittney Shea, a single mom with two teenagers, has been sued three times by Eastern Shore Rural Health since 2021. She and both of her children have chronic health conditions that require them to see doctors and specialists frequently, and the $25 co-payments add up quickly, she said.

Most recently, the health center sued her last October for about $2,000 in medical bills and an additional $760 in lawyer fees and court costs, records show. The money was garnished from multiple paychecks from her Walmart job.

Shea is aware that she ends up paying more through garnishments than she would if she paid her medical bills on time. But she said the money just isn’t there on the front end, especially when she has been out of work due to health emergencies. Sometimes she avoids seeing doctors when she is feeling sick to avoid owing more money.

The cycle of lawsuits and garnishments has made it harder to provide for her children, she said. “You expect this money, but then they’re garnishing you,” she said. “Now you got to figure out how you’re going to feed them, how you’re going to put gas in your car to go back and forth to work, how you’re going to pay your rent.”

Many regions served by community health centers lack primary care options and have

a real need for them. That was the case in Hutchinson, Kansas, a historic salt mining town northwest of Wichita, in the 1990s when the local hospital came up with the idea to start PrairieStar Health.

When Aimee Jones started working at PrairieStar in 2015, she had only ever been on the patient side of debt collection. After a difficult divorce decades earlier, she’d had trouble paying outstanding medical bills and filed for bankruptcy to avoid having her wages garnished.

As a patient accounts representative, Jones was responsible for handing patients’ debt over to an outside collection agency once she had exhausted efforts to get them to pay. PrairieStar would send out three statements and two collections notices and often make an additional phone call reminding patients of their unpaid balances and encouraging them to set up a payment plan. The last notice told them that their bill would be sent to collections. (Anderson, the PrairieStar CEO, told ProPublica the collections agency also sent patients multiple notices before escalating to lawsuits.)

Jones said she convinced her bosses to change some policies in favor of patients. The company was initially sending bills as low as $30 to collections, which Jones felt was pointless because the outside agency took a third of the money. She pushed PrairieStar to raise the threshold to $200 in outstanding debt. In more recent years, that amount increased to $500, she said.

In Kansas, unlike Virginia, lawmakers have not significantly limited how health care providers can recover medical debt. Kansas is also one of 10 states that has chosen not to expand Medicaid, leaving thousands of people unable to get health insurance — and potentially more reliant on community health centers.

Many of the patients who qualified for discounted care based on their income had no insurance, Jones said. And even with lower fees, some struggled to afford medical care at PrairieStar. “You don’t stay on top of it or you come in a lot, it’s going to accumulate quite fast,” Jones said. According to the health center’s financial assistance policy, not all services qualify for discounts.

Jones tried hard to convince patients to pay even a few dollars each month so they could stay out of collections. Often, it worked. She was aware that some people, especially those on fixed incomes, had almost nothing to spare. If they didn’t pay their bills or sign up for a payment plan within about six months, she handed their names over to the collection agency.

Jones could request permission to write off some bills for people who had endured extreme hardship, like a woman whose baby died in a house fire or another whose boyfriend and son died in a car accident. But she couldn’t help everyone.

Once the collection agency referred a case for a lawsuit, it was largely out of Jones’ hands, she said. PrairieStar hired a company that handles collections for hospitals in many Kansas counties — Account Recovery Specialists Inc., which has a documented history of requesting arrest warrants for patients who don’t show up to court. (The collections agency told ProPublica that the warrants were ordered by a judge and that it could not discuss its contract with PrairieStar. It has previously denied using the threat of jail to get people to pay.) Each summer, the agency would send PrairieStar a long list of patient accounts deemed “uncollectible” because they had no income or assets, Jones said.

Jones, who retired last year, looks back on nearly a decade of work with a mixture of pride and sadness. She wonders if PrairieStar could have convinced more people to agree to payment plans if it hadn’t contracted with an outside agency. The health center’s patients would have benefited from a law like Virginia’s, she said, which prevents providers from garnishing wages of patients receiving financial assistance.

“We serve the poorest of the poor. These people don’t have any money,” Jones said.

Pursuing debt in court is a choice, and some community health center leaders have opted out.

Several years before Krista Postai founded the Community Health Center of Southeast Kansas in the state’s poorest region, she worked at a hospital that took extreme measures to collect medical debt. As part of her job, she fielded calls from patients unhappy with the billing process. At times, she said, patients reported receiving warnings that they would be sent to collections, even though they hadn’t received a bill.

When she began applying for grants to start her own clinic in 2002, she knew there had to be another way. “If your goal is really keeping people healthier, it makes more sense to deliver care at the lowest cost possible and not drive them into ERs and hospitals,” she said.

Hospitals do not make much from suing their patients, according to research in several states. (Experts did not know of similar studies on community health centers.) One study of Virginia hospitals found that wage garnishment brought in just a fraction of a percent of their total revenue, on average. But patients can see their finances devastated by these lawsuits, especially with the added interest charges, lawyer fees and court costs.

The National Consumer Law Center, a nonprofit that focuses on consumer protection, urges states to set limits on health care providers collecting medical debt. Their recommendations include capping interest rates for debt at 2% a year — much lower than Kansas’s 10% maximum — and prohibiting lawsuits for patients who qualify for financial help. It recommends banning wage garnishment for all patients.

Community health centers should be held to the same requirements when possible, said Berneta Haynes, policy adviser for the center. “The idea here is that certain types of egregious and aggressive debt collections really should just be banned,” she said.

Community Health Center of Southeast Kansas, based in a county with a poverty rate almost twice that of the state as a whole, provides care to many people who can’t afford to immediately pay their bills. Postai said the health center makes “every reasonable effort” to collect money from patients, as required by federal law. But she is determined to never outsource that work to a collections agency, despite the weekly calls she gets from companies hoping to purchase the health center’s debt.

The center’s internal policy says it will not send patients to collections “to ensure that patient dignity is maintained.” Its peers, she said, should do the same.

“Most people try to pay,” she said. “It makes no sense to take an already stressed population and stress them further.”

Instead, the health center finds creative ways to pull in more patients — using federal grants to open discount pharmacies, serving patients at jails and prisons, partnering with other local nonprofits. It has branched out to neighboring counties with no other sources of affordable medical care. Last year, it wrote off about $5.3 million of bad debt from patients who didn’t pay their bills, about 5% of its total revenue, federal reports show.

Postai said the clinic is willing and able to sustain the loss, and she cringes thinking about patients at PrairieStar and similar health centers who may avoid returning there for medical help.

“That’s a big hole in the safety net,” she said.

The post ‘Affordable’ health centers sue patients for as little as $59: Bills ‘came out of nowhere’ appeared first on Raw Story.