Most casinos in Las Vegas take sports bets, but that’s not where the real money is. The bulk of their profit comes from games like slot machines and blackjack.

Many states have legalized online sports betting in recent years, but a handful have learned the same lesson: If the goal is to increase tax revenue, the big money comes from allowing a full legal casino, slot machines and all, on your phone.

Pennsylvania is one of seven states to have done that. It legalized both online casino gaming and online sports betting, for ages 21 and up, in 2017.

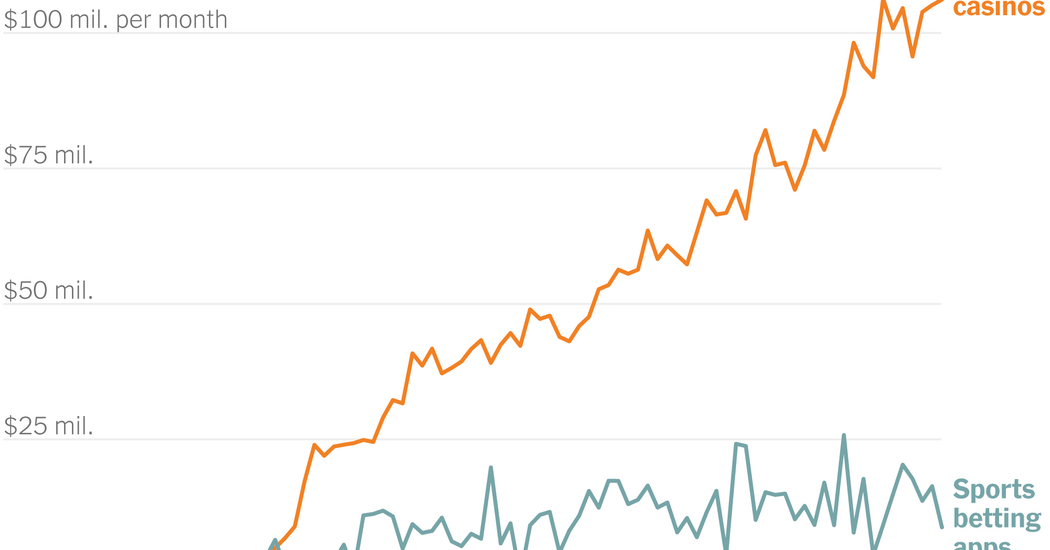

By last year, the state was collecting $1.05 billion in taxes from digital casinos, compared with $188 million from sportsbook apps. The revenue from casino games is significant: Pennsylvania’s entire state budget is about $50 billion.

The state taxes online slots at a higher rate, which explains some of the difference. But Pennsylvanians are also losing a lot more money to online casino games than they are on sports bets.

Donna Buschelberger, 57, lives in Littlestown, Pa., and works as a home care worker. She said she had never gambled until she downloaded casino apps during the pandemic. In the last few years, she has lost at least $15,000 on BetMGM Casino, mostly playing the game Slingo, which is a fusion of bingo and slot machines.

Her car was repossessed, she said, and she is facing eviction after missing rent payments. She is also part of a class-action lawsuit against the casinos alleging predatory marketing tactics, yet she was in the middle of gambling when I called her.

“If they were to close down the site tomorrow, I would be mad because I couldn’t do it, but it would be helping me in the long run,” she said. (BetMGM did not respond to a request for comment.)

Thirty states permit online sports betting, but only seven have legalized online casinos, though more may soon join in. A bill legalizing online casinos in Maine awaits the decision of Gov. Janet Mills, who has not signaled if she will sign it. Lawmakers in several other states, including Hawaii, Massachusetts, New York and Ohio, are also considering allowing online casino gaming.

Big tax collections

The seven states with legal online casinos collected a total of $2.1 billion last year from gambling apps, according to Legal Sports Report. Over the same period, online sportsbooks generated about $2.9 billion in tax revenue for the 30 states where they are legal.

States with both have seen tax revenue from casino games far outpace revenue from sportsbooks:

Edgar Gonzales Jr., a Democrat in the Illinois House of Representatives, would like his state to join them. Mr. Gonzales, who last year was a sponsor of a bill to legalize online casinos, said he would like more money for programs related to homelessness and education, without raising income taxes.

He said federal spending cuts had made the case for legal online casinos more compelling. “It’s a matter of how can we come up with our own money,” he said. “Because we can’t rely on the federal government for it.”

When New Jersey legalized online casino games in 2013, Michael Doherty, a Republican, was the only state senator to vote against it. He continued voting against anything to make gambling easier through his time in office, he said.

Mr. Doherty said that gambling is a “negative activity that destroys a lot of lives,” but also that New Jersey did a poor job of setting tax rates. Pennsylvania, for example, imposes a tax rate of 50 percent on online slots. This year New Jersey raised its tax rate on online casinos to 19.75 percent, from 15 percent.

“When you guys start collecting 50 percent of the profits from the gambling revenue, then, you know, wake me up,” Mr. Doherty said.

In most states, online casinos are taxed at a higher rate than sportsbooks because they have higher profit margins and more predictable revenue.

The lure of slots

Traditional slot machines were once the most common reason people called the problem gambling hotline run by the Council on Compulsive Gambling of Pennsylvania. But in the years since the state legalized online gambling, online casino games have become the No. 1 reason for calls, ahead of physical casinos and sports betting.

The group’s executive director, Josh Ercole, noted that many people in Pennsylvania live long distances from an in-person casino, but anyone can play online slot machines “without having to get out of bed.” A spin on an app often takes less than two seconds, he said, while a traditional slot machine in a casino could take up to 15 seconds.

Melissa Stewart, 45, from Charleston, W.Va., said as soon she got sober from drugs she got into gambling. She said that she had lost around $19,000 from online casinos, and that it had prevented her taking her child out for activities.

Ms. Stewart, a parking enforcement attendant, says the tax revenue from online gambling is a money grab by the government: “They don’t care if a person’s addicted and they just keep going to keep on. They just want to get their money regardless.”

Despite her losses, she is still active on the apps for hours a day. “It’s like I’m trying to win back the money that I’ve lost,” she said. “I do it at home, at work, everywhere.”

Different incentives

Expanding online casinos to more states could be a boon not just for those governments, but also for large casino companies. DraftKings and FanDuel, for example, built their brands on fantasy sports and sports betting, but their casino apps generate roughly four times the profit of their flagship sports apps in states where both are legal, according to tax records. Those companies declined to disclose user numbers for their respective casino apps.

On sportsbook apps, many bettors wait hours or days for a game. In casino apps, gamblers can spin slot machines again and again. About half as much money is bet on sports in July than in September because there are fewer major sports events in July (and no football). Online casinos don’t have this issue, with little variation in activity through the year.

In Pennsylvania, the state collected more tax revenue from online casinos than physical lottery tickets for the first time last fiscal year.

Marcus Simon, a Democratic delegate in Virginia’s General Assembly, is cosponsoring legislation to legalize online casinos. Gambling is everywhere already, he said, with offshore betting and other ways to skirt state bans, so it’s better to legalize and regulate it, adding consumer protections and ways to detect problem gambling.

“I think on balance folks that want to do this are finding ways to do it,” he said.

Scott Moore, 45, a pet sitter in Bryn Mawr, Pa., says he gambles through eight licensed casinos in the state but also bets with about 40 sweepstakes casinos, sites that operate in a legal gray area and send no tax money to the state.

His FanDuel Casino app lists a total loss of almost $4,000, but he said a single $10,000 win from a 20-cent spin on “Red Hot Joker Cash Eruption” on the Golden Nugget app has made him profitable overall.

“I will play while I watch TV,” Mr. Moore said. “I definitely play while I walk a dog or when house sitting. I play to kill time.”

Michigan legalized online casinos and sports betting in 2019 with near unanimous bipartisan support in the Legislature and from Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. Ed McBroom, a Republican, was one of just three state senators who voted against the bill.

Mr. McBroom said the state’s collection of tax money from gambling creates a conflict of interest, incentivizing the government to get citizens to gamble more. But he said gambling in Michigan and the United States was still in its expansionary stage.

“I don’t see it changing anytime soon,” he said. “I’m clearly in the minority.”

Ben Blatt is a reporter for The Upshot specializing in data-driven journalism.

The post States Are Raking In Billions From Slot Machines on Your Phone appeared first on New York Times.