At 15, Leonardo DiCaprio sat down with a pile of rented VHS tapes and gave himself a crash course in movie history. He’d recently, and miraculously, landed his first major movie role, playing opposite Robert De Niro, and figured he’d better brush up on the classics, fast. He watched film after film, but no performance awed him more than the one James Dean gave in Elia Kazan’s 1955 East of Eden, as Cal Trask, the rebellious son of a disapproving, rigidly principled, Bible-thumping father. Craving attention, he’s a cutup, a jittery post-adolescent clown, a kid perpetually showing off on the monkey bars; if only his yearning could be seared right out of him, the way a teenager burns off calories. Dean’s Cal is simultaneously self-protective and exposed—the tenderness he needs is elusive, a nameless butterfly heartbeat he can hear in the dark but can’t get close to.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

DiCaprio could hardly believe the depth of Dean’s onscreen vulnerability. As he says now, “Performances like that, that’s what’s intriguing to me. Showing that or exploring that, and not having that hardened shell.” Could he do that? Could he be that? By that point Dean had already been gone for 35 years, leaving behind only three credited film roles. And still, he’d unwittingly made an investment in the future of movies, and in an actor he’d never meet. As moviegoers or performers—or both—we have no way of knowing where ghosts will lead us, or of measuring their generosity.

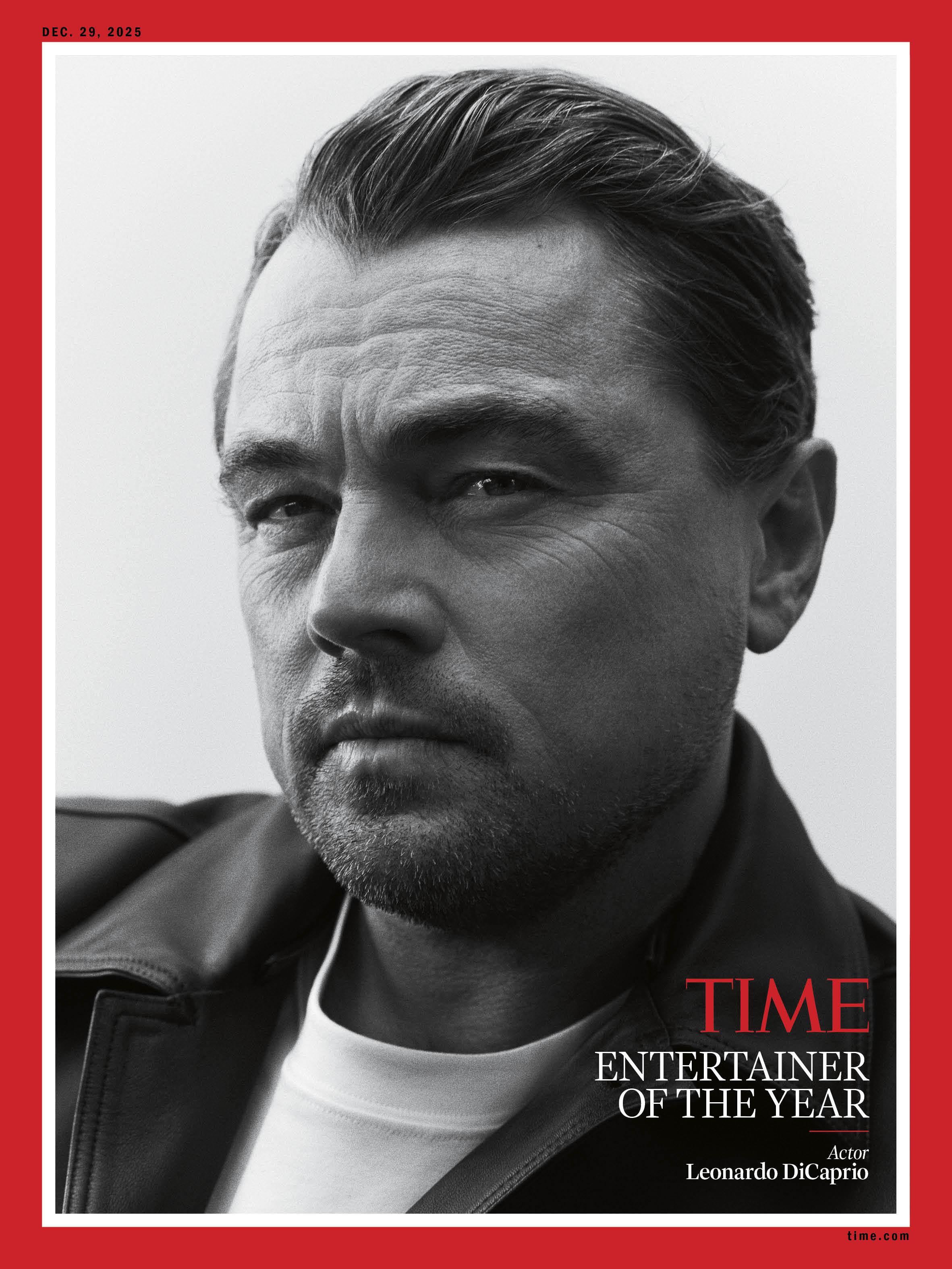

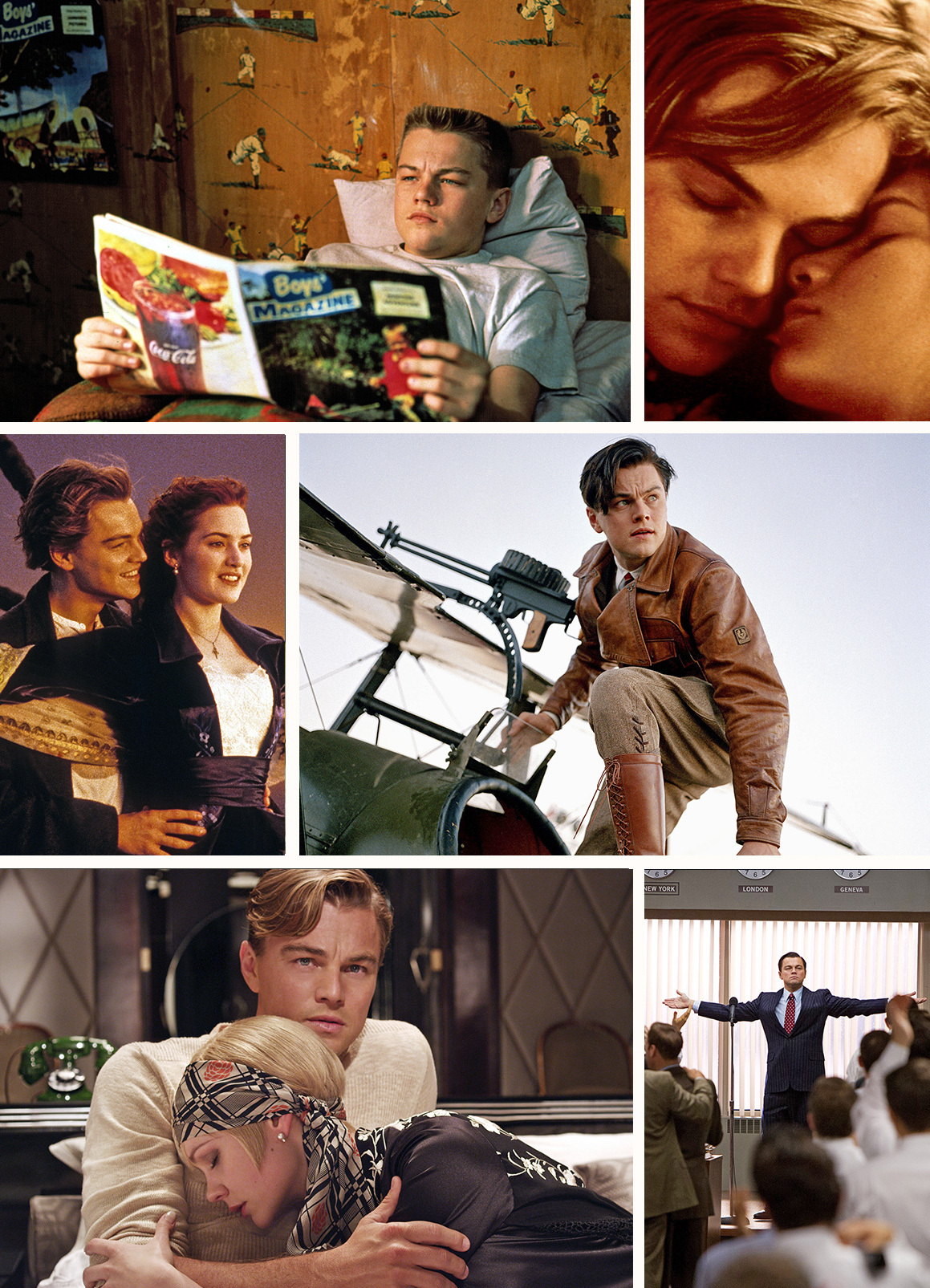

DiCaprio, now 51, has built a career many of his peers would envy. In that first film, 1993’s This Boy’s Life, adapted from Tobias Wolff’s memoir, he played young Toby, who’s nearly broken by the casual cruelty of De Niro’s character, a nightmare stepdad who lives by a code of hothead masculinity. At the time, virtually no one who saw this performance could believe this kid, his juvenile-delinquent swagger tempered by quizzical boyishness—he defined that fuzzy, confusing space between almost-a-man and still-just-a-kid so purely that you felt you were suffering through it yourself. Hollywood knew what it had: DiCaprio was offered what would have been life-changing money—certainly for a kid who’d been brought up modestly, as he had, often in rough L.A. neighborhoods—to appear in the Disney comedy Hocus Pocus; instead, he played a mentally impaired teenager in Lasse Hallstrom’s ardently unsentimental independent coming-of-age drama What’s Eating Gilbert Grape.

Click here to buy your copy of this issue

DiCaprio, who has been nominated for seven Academy Awards and won one, has a knack for making the seemingly wrong choice that turns out to be completely right—perhaps just another way of saying he has good instincts and he knows when to follow them. He works with people he trusts; he invests in projects he believes in. But there are intangible factors too: he has a face we don’t tire of looking at. More than 30 years into a career built on making largely unpredictable bets, audiences still want to see him, maybe more now than ever—even as a washed-up revolutionary with Iron Butterfly facial hair, the character he plays in Paul Thomas Anderson’s shaggy-dog father-daughter odyssey One Battle After Another.

DiCaprio’s Bob Ferguson is now middle-aged and has gone into hiding. Even more importantly, he’s a single dad, devoted to his teenage daughter Willa, played by newcomer Chase Infiniti. Like most dads, Bob is out of touch with kids today; as Willa heads out with friends, he grills her about where she’s going and who she’s going with. In the old days, Bob could be set on fire by the latest cause. Now that flame is just a flicker, and he spends his days dressed in a layabout’s plaid grandpa bathrobe, smoking weed. But there’s still some fight in him; it’s merely taken a different form. His fierceness, driven by the need to protect his child, is the motor of a movie that people have continued to see (and talk about) for months after its September release.

You could argue, of course, that people love talking about most of the movies DiCaprio has starred in, from Titanic to The Wolf of Wall Street to Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. What does it mean to be the actor of the moment, one moment after another? And maybe the bigger question is, How does anyone pull it off? DiCaprio may have figured it out better than most. And still, he refuses to pretend he has the answers.

DiCaprio doesn’t exactly shy away from interviews, but he does fewer than you might think. And this time, when we sit down to talk—on an October day when he’s recovering from pneumonia, no less—he explains why he cares so deeply about One Battle After Another. “I’ve been thinking a lot about how often there have been truly original story ideas like this, with no link to anything historical, no past characters, no genre, no vampires, no ghosts, no anything,” he says. “It was somewhat risky for the studio to take this on, and what they’re banking on, I think, is the appeal of Paul’s storytelling and the sort of fierce originality of his process.”

Read More: One Battle After Another Is a Potent Portrait of America

It’s not lost on DiCaprio that One Battle is also about having something at stake, a core idea that seems to resonate with audiences in our precarious world. In addition to being a wily, entertaining comedy, the movie suggests that it’s essential to have principles to cling to. “It’s about human beings in a world where we all feel stifled to say what we believe or stand for something, because, you know, it’s a scary world out there.”

DiCaprio makes a wholly believable dad, a character shaped, he says, by talking to Anderson about his “fear of the future for his children, what it’s like for him to be a father in the world that we live in, and what humanity and politics in the world are going to be like for his offspring.” He loved working with Infiniti, he says; she made it easy for him to slip into the role. “You go, ‘Oh yeah, I’d stand in front of anything for this person,’” he says. “She’s just so incredibly good-hearted and sweet you want to protect her.” And working with DiCaprio, Infiniti felt not only that sense of protection, but a warmth and generosity she wasn’t prepared for. “I mean, he’s Leonardo DiCaprio, so it’s a no-brainer that he’s passionate about the craft,” she says by phone from London. “But getting to see his expertise up close and just observe him, and then to find out on top of it that he’s a very kind and genuine person.” He was, she says, the perfect person to learn from. “It was my first film set, and I didn’t know what to expect. And he would guide me in any way he could and offer advice. But also just him being there, making himself just a person to have a conversation with, about anything—it was such a beautiful thing.”

When One Battle After Another opened, all the beard-stroking box-office experts tsk-tsked loudly about how it wasn’t “on track” to recoup what it had cost. As it turned out, though, the film has done just fine: by mid-November it had made more than $200 million worldwide—no small feat in a here-today, streaming-tomorrow theatrical-release climate, especially for an original movie clocking in at nearly three hours.

Beyond dollars and cents, the more people talk about a picture, the more likely it is to have a long life in the cultural memory. Anderson wrote the script using oddball-genius novelist Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 Vineland as an inspiration. It’s a comedy with grim underpinnings, set in a society where violence seems to be the only answer. But it’s also exhilaratingly weird: Where else are you going to find a group of rebel nuns known as the Sisters of the Brave Beaver, or see Benicio del Toro as a cooler-than-ice-cream martial-arts instructor named Sensei Sergio St. Carlos? DiCaprio sees the appeal of One Battle not just as its star, but also as a guy who goes to the movies himself. (Yes, he goes—all the time, he says.) “I just love that it’s such a conversation piece,” he says. “In my community, people like talking about it, and that’s one of the reasons you make movies. At the end of the day it’s like, ‘Wow, this maybe had a little effect on people.’”

To make a movie as audaciously strange, and as risky, as One Battle After Another, a director needs a star who’s on his wavelength. Anderson had long wanted to work with DiCaprio. It was just a matter of finding the right project. The two were ultimately brought together by the late Adam Somner, a first assistant director who’d worked with each of them on separate projects. Anderson knew they’d get along; he just didn’t know how well, or the degree to which DiCaprio would set the tone on set. “If you’re the star of the movie, not to mention a very big movie star and a big movie star for a very long time, your behavior informs everything. That gives an indication to the crew of what kind of film they’ve signed up for,” Anderson says. “His leadership means his presence, his availability, his unfussiness. It’s that simple. There’s no bullsh-t.”

Promotion may not be any actor’s favorite part of the filmmaking process, but especially for someone who generally shies away from it, DiCaprio seems completely at ease with this one. He’s a person who still believes in movies and what they can mean to people—and he knows the effect they have isn’t always immediate. All of these are reasons DiCaprio has worked so hard to promote this movie, from appearing in TikToks (with Infiniti as “director”), to participating in dual Q&As with Anderson, to showing up, with co-star del Toro, on Jason and Travis Kelce’s popular New Heights podcast. It’s worth noting, again, that One Battle After Another represents the sort of financial risk few studios are willing to take these days. And if no film is easy to make, this one came with particular challenges. “We shot over nine months, over 100 days,” Anderson says. “If that doesn’t make you cranky, then I don’t know what will. So it’s great that we’re all still sort of in love with each other.”

People who care about movies, even as they watch the viewing experience become eroded by the popularity of streaming, often wonder if we have any real movie stars left. DiCaprio is as close as we’ve got. He chooses his roles carefully, while also using his clout—through his production company, Appian Way—to make movies he cares about. This is how he was able to swerve away from playing unthreatening, albeit undeniably charming, heartthrobs like Titanic’s Jack Dawson, or the pensive, impulsive Shakespearean swain in Romeo + Juliet. Those were great roles for a young actor.

But DiCaprio entered new territory—you might call it the beginning of his great, middle era—with his role as messed-up megacapitalist and onetime Hollywood charmer Howard Hughes in The Aviator. From that point, he rushed toward, rather than away from, characters who are more complex, maybe even close to reprehensible, than they are likable. Whether he’s playing the dazzled and dazzling social climber Jay Gatsby, or Killers of the Flower Moon’s Ernest Burkhart, a white man in post–World War I Oklahoma who, at the behest of his scheming uncle, attempts to murder his Osage wife, he finds the subtlest and most powerful ways of zeroing in on the murkier corners of masculine fragility. In this way, he wields influence like no other movie star: it’s the chiaroscuro textures he’s seeking, rather than the most flattering light.

How do you prepare for a career like that? The short answer, maybe, is that beyond being alive to the world around you, you can’t. Growing up, he would try to crack his parents up by impersonating their friends, many of them counterculture hippie types. Rambunctious from the start, he was fired from Romper Room for slapping the camera, an inauspicious show-business entrée if ever there were one. Later, he watched as his stepbrother landed a few commercials; he wanted to do that too, but became frustrated when no agent would represent him. He finally landed one at age 12, and at that point, he says, he became his own stage parent. “I was the person telling my dad and my mom, ‘Get me to auditions! We need to do this! Try to pick me up from school at 4 o’clock!’” He doesn’t come out and say as much, but it’s clear his ambition was less to become a big movie star than to simply find a vocation that would ensure a viable existence after public school in L.A., which he hated. “I was like, ‘This is a bummer! I gotta start thinking about what I want to do for work immediately.’”

DiCaprio landed a role on the sitcom Growing Pains; then he needed to be freed from his contract to appear in This Boy’s Life. Mercifully, it worked out. At first, when he’s asked about what it was like to grow up in the movie business, he says he doesn’t think he did. Then he remembers: Of course he did. Before he fully knew what he was doing, he may have horsed around on set a little too much. But soon he learned the importance of professionalism: “What I remember most about that age is people underestimating you and your ability to comprehend what needs to be done.” He recalls times when filmmakers would assume he couldn’t understand certain complexities of performing. He’d think, “I get it, I get it. Speak to me like an adult.”

If DiCaprio never set out to be a huge star, there’s no way around it: he’s one now. He admits he hasn’t entirely figured out how to navigate the choppy waters between maintaining his privacy and being a public figure whose life is up for scrutiny. “It’s been a balance I’ve been managing my whole adult life,” he says, “and still I’m not an expert. I think my simple philosophy is only get out there and do something when you have something to say, or you have something to show for it. Otherwise, just disappear as much as you possibly can.” He admits that even though the early success of Titanic bought him freedom, he also found the attention intense and overwhelming; he was sure people were sick of him. And he began to think about how to survive in a line of work he loves. “I was like, OK, how do I have a long career? Because I love what I do, and I feel like the best way to have a long career is to get out of people’s face.”

Even if acting is one of the purest forms of expression we have, it still needs to be part of a greater scheme of human interaction, and DiCaprio cares about the world outside his own sphere. He produced and narrated the 2007 documentary The 11th Hour, about the dire future faced by our planet, and his commitment to global environmental issues hasn’t waned. In 2021, he joined with a group of experienced conservation scientists to found Re:wild, dedicated to working alongside Indigenous people and local communities to preserve and protect vital ecosystems. “It was alarming 10 years ago, and now we’re in a situation where basically, we’re at the tipping point. Everything that scientists have predicted is almost happening like clockwork,” he says, pointing out the massive wildfires that have affected the world, including his own home turf of Los Angeles. He wants to do what he can to help, which is where Re:wild comes in, with its goal of “making Indigenous people the stewards of the land, protecting ecosystems as a way to -mitigate climate [change], to sequester carbon from the atmosphere, to protect biodiversity, to protect nature.” He’s also placing some of his hope in innovation: “God willing, with our different political shifts, there is going to be a way that technology figures out something cheaper or something that will stop us from burning fossil fuels at the rate that we have.”

The key, maybe, is that DiCaprio cares about science and hope in equal measure. In early November, he spoke at his friend Jane Goodall’s funeral: “When most of us think about environmental issues, we tend to dwell on destruction and loss,” he said. “And I’ll admit it’s something I always struggled with myself. But Jane led with hope, always. She never lingered in despair. She focused on what could be done. She reminded us that change begins with compassion, and that our humanity is our greatest tool.”

Humanity is something DiCaprio thinks a lot about. He acknowledges the role AI might play in the future of movies, and while he mourns the fact that talented and experienced people could lose their jobs because of it, he isn’t ready to write off the possibilities just yet. “It could be an enhancement tool for a young filmmaker to do something we’ve never seen before,” he says, though it’s clear the word enhancement is critical. “I think anything that is going to be authentically thought of as art has to come from the human being. Otherwise—haven’t you heard these songs that are mashups that are just absolutely brilliant and you go, ‘Oh my God, this is Michael Jackson doing the Weeknd,’ or ‘This is funk from the A Tribe Called Quest song “Bonita Applebum,” done in, you know, a sort of Al Green soul-song voice, and it’s brilliant.’ And you go, ‘Cool.’ But then it gets its 15 minutes of fame and it just dissipates into the ether of other internet junk. There’s no anchoring to it. There’s no humanity to it, as brilliant as it is.”

It’s not surprising that music should come up in the conversation. Isn’t acting a little like music, a mode of communication that uses words as tools yet also goes beyond them? DiCaprio says he loves old blues (Blind Willie McTell, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Willie Johnson, Blind Blake—“A lot of blind guys,” he says), but also the Ink Spots, the Mills Brothers, and Johnny Mercer (“I like that sort of World War II–era harmony. It keeps me calm and chill”). He’s a huge Django Reinhardt fan, he says. “But then, there’s Al Green and Stevie Wonder.” He could go on. He’s not thinking about the clock.

The most surprising thing about Leonardo DiCaprio is how funny he is, and how, despite taking his work very seriously, he doesn’t seem to take himself very seriously at all. Has he ever been starstruck? A lot, he says, citing his first encounters with Meryl Streep and Diane Keaton, who starred with him in Marvin’s Room, as examples. He was awed by them both, but he loved Keaton especially. “She had the most incredible laugh,” he says. “It would echo through the entire set, and she made you feel like the funniest person in the world. I mean, burst-out-loud laughing. I’ll never forget it. I kind of lived to make her laugh every day on set, because it was so infectious. She was incredible.”

Like many actors, Keaton also directed, and while DiCaprio has said he doesn’t aspire to do so, he gently sidesteps the question in our interview. He does, however, have ideas about what the future of filmmaking will look like: His take is that we have no idea what’s coming, and we shouldn’t try to predict it. “I was just thinking the other day, I wonder what the next most shocking thing is going to be in cinema. Because so much has been done that has moved the needle, and some of these directors are so talented right now and doing such a multitude of different things at the same time,” he says. “What’s going to be the next thing that rattles people and shocks people cinematically?”

DiCaprio has talked for an hour, pneumonia be damned, answering every question as clearly and carefully as he can. If he’s occasionally evasive, he’s so subtle about it that his digressions end up becoming answers in themselves. He almost seems eager to please, not in an ingratiating way, but as a means of making sure the job at hand is done right; he’s not going to be the guy who gums up the works. He comes off as relaxed and unfussy, in some ways almost remarkably unlike a movie star, and more like the unguarded, open-faced kid of This Boy’s Life, What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, or Romeo + Juliet. His eyes, though, are definitely movie-star blue, Peter O’Toole blue—big-screen blue. They’re a symbol of everything we stand to lose as our screens get smaller and smaller. James Dean slipped away from us even before we could fully grasp what he meant. DiCaprio, on the other hand, has stuck around. We’ve had the pleasure of first watching him grow up onscreen, before growing into roles of extraordinary emotional complexity and delicacy—roles that confront various visions of adult masculinity, suggesting the grand range of what men can be, including how they can fail themselves and others. He built a future on what Dean left behind and became a movie star in the process, but the kid who begged his parents to get him to auditions lives on. All he ever wanted to be was an actor. —With reporting by Simmone Shah

Set Design by Whitney Hellesen; Styling by Evet Sanchez; Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua; Production by Crawford & Co Productions

The post Leonardo DiCaprio Is TIME’s 2025 Entertainer of the Year appeared first on TIME.