Lauren LaRusso was on parental leave from her job as a lawyer for the State of New Jersey when the first call came in about the largest sporting event in the world. Could she prepare a document? She was at home, in a robe, a newborn in her arms. She said sure.

Bruce Revman was on his first day back at New York City’s tourism agency when he spotted the large cardboard box in his Midtown Manhattan office. He had inherited a stack of documents, beckoning him to dig in to a gigantic task.

It was 2018, and these two public servants, one on each side of the Hudson River, had no knowledge of their counterpart. But over time they would toil in obscurity through a pandemic, several election cycles, and a cyclone of paperwork and Zoom calls, to bring the World Cup and its highly coveted championship game to New Jersey.

“Bruce and Lauren are the M.V.P.s,” Phil Murphy, the governor of New Jersey, said in a telephone interview last month, “especially when it was cold and dark and nobody was looking.”

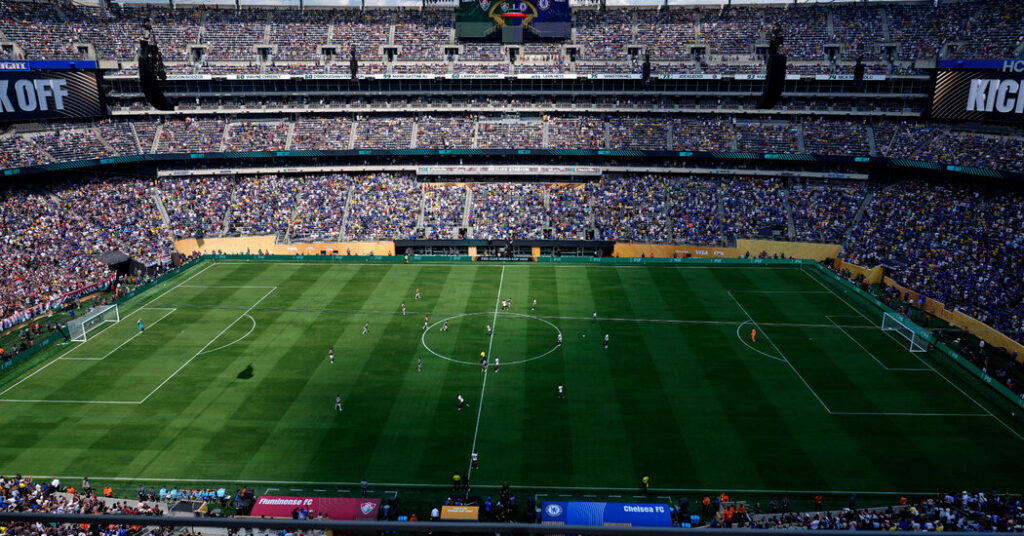

The World Cup extravaganza will descend on the Meadowlands this summer with a regional economic boon estimated by some at $3 billion — including a projected 14,000 jobs created surrounding the eight games at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J. — thanks in large part to two government employees.

Mr. Revman, now 68, was the expert on tourism and big events. Ms. LaRusso, 44, was senior counsel to the governor. In the beginning, there was no directive to work together on the joint World Cup bid. It was more by default, each one taking the lead from their sides of the river. But an interstate symbiosis was soon forged.

“Bruce and my personalities have always, for lack of a better word, married well together, like yin and yang,” Ms. LaRusso said. “He would draw up an idea, and I would operationalize it. It’s just a very nice partnership.”

The work started in June 2018, when FIFA awarded the 2026 World Cup to the United States, Mexico and Canada. For the first time, three nations would serve as hosts, and the tournament was expanded from 32 to 48 teams, with 104 total matches.

Immediately, the jockeying among cities hoping to host games began, and it is no secret why. FIFA reported $7.5 billion in revenues for the last tournament in Qatar, where the final alone was watched by an estimated 1.5 billion people. The 2026 final on July 19 is expected to surpass that.

A list of about 19 potential U.S. cities was whittled down to a shorter list of 16, from which FIFA chose 11. New Jersey, which hosted seven games in the only other U.S.-based World Cup, in 1994, seemed an obvious choice to get at least a few games, if not the final. Its cosmopolitan backdrop; a large, if bland, stadium; ample hotel space; and the region’s hefty financial and political clout gave it an edge.

Ms. LaRusso and Mr. Revman began shortly after it was announced that the World Cup was coming to the United States, when their respective bosses asked them to shore up the Meadowlands’ pitch to FIFA.

“We had a team at first on the New York side, but some of those people left,” Mr. Revman said. “So by default it was a team of one — Bruce Revman.”

At this point, the bid was, in Ms. LaRusso’s words, a “side hustle” to their main responsibilities. But it became significantly more complicated beginning in 2020 with the Covid-19 pandemic, when anyone working for a government agency was helping search for respirators, hospital beds and gravesites. There was no time to produce estimates for hotel beds or a security plans for soccer fans six years hence.

As the height of the health crisis began to subside, and Mr. Revman and Ms. LaRusso turned their attention to FIFA’s countless requirements and hyper-detailed questions, they discovered that amid the despair of the pandemic, many of their colleagues were eager to assist.

The World Cup, it turned out, signaled hope that one of the hardest-hit regions in the country would emerge from the cold and dark.

“It was a moment of, ‘Hey, we are going to get out of this,’” Mr. Revman recalled. “For a lot of us in government trying to deal with day-to-day stuff, there was solace to know that we were going to be OK.”

As the pandemic wore on, the pair brainstormed remotely, Ms. LaRusso from her family’s home in central New Jersey, Mr. Revman in the Manhattan apartment that he shares with his wife. They would not meet in person until a lunch with Ms. LaRusso’s boss at a Newark tapas joint in 2021.

“Until then I had only seen Lauren on a screen,” Mr. Revman said. “We allotted an hour and a half, but we stayed so long that we were the only ones in the restaurant.”

Early on, Governor Murphy, who wanted the World Cup to be part of his legacy, instructed his chief of staff to give Mr. Revman and Ms. LaRusso unfettered access to him, even as his re-election campaign ramped up in 2021. Whenever the duo needed a meeting, they got it.

“I thought the campaign staff was going to kill us,” Ms. LaRusso said.

In September of that year, they hosted a critical daylong event. A group of about two dozen FIFA officials were touring the various candidate cities, and Mr. Revman, Ms. LaRusso and their team organized the visit to New York/New Jersey. This would be the grand presentation, a mix of meticulous logistical details with a layer of theatrics at the Hyatt Regency in Jersey City, Covid-19 protocols still in place.

Governor Murphy spoke, as did his wife, Tammy Murphy, who has been involved in the bid effort from the beginning. So did Bill de Blasio, then the mayor of New York. The governor concluded by telling the FIFA delegates, “On July 19, 2026, you will raise that FIFA trophy here in the Meadowlands.” Then one last touch: The curtains in the conference room drew back to reveal a full picture-window view of the Statue of Liberty.

The group then boarded buses for the Meadowlands and a tour of MetLife Stadium, which Mr. Revman and Ms. LaRusso both knew was the weakest link in their bid. The stadium is large enough (roughly 82,000 for soccer), but it is remote, and it lacks the kind of luxury and tinsel that other stadiums have. It hosted the Super Bowl in 2014, which was a transportation nightmare.

When the stadium tour was finally over and the FIFA delegates had boarded their bus bound for Philadelphia, a sense of relief washed over Ms. LaRusso, Mr. Revman and their team. They had concluded a long, pressure-packed day, preceded by years of preparation, and they were proud of their work. Celebratory beers and snacks appeared. Men in suits removed their ties and women kicked off their heels and strolled onto the field.

But suddenly, the FIFA delegates reappeared, emerging from the stadium tunnel, strolling back toward them. Near-panic set in. What had they forgotten in their presentation? What questions had they failed to answer?

It turned out a mechanical problem with the bus forced a delay. While the officials waited, they wanted to play soccer — and even American football — in the famous stadium. For the next hour, that is what they did. They even took turns kicking field goals.

“The new bus arrived, and they didn’t want to leave,” Mr. Revman said.

A few months later, New Jersey was confirmed as one of the 11 American locations to host a match. Plus, the Meadowlands was still in the running for the final game. New York/New Jersey was pitted against Los Angeles and Dallas, both of which feature gleaming new stadiums with air-conditioning and roofs. MetLife has no roof, and July in the Meadowlands can be brutally hot or overwhelmed by lightning storms. So, Ms. LaRusso and Mr. Revman arranged surveys on lightning probabilities and prepared arguments that the lack of a roof benefits the natural grass field, a crucial requirement for World Cup soccer.

In 2023, Mr. Revman and Ms. LaRusso began working for the newly formed host committee. It was the first time they were officially working for the same organization.

Then, on Feb. 4, 2024, FIFA made its announcement. Everyone involved in the Meadowlands bid, including Ms. LaRusso, Mr. Revman, the New Jersey governor and his wife, gathered at the stadium to watch. When they heard that New York/New Jersey had earned the final game, they leaped to their feet and celebrated. Gianni Infantino, the FIFA president, cited the area’s cosmopolitan makeup and diversity when announcing the choice.

In January 2025, the host committee, with Ms. Murphy as president, named Alex Lasry, a sports executive whose family owns the Milwaukee Bucks of the N.B.A., chief executive. He kept the two civil servants in place, now as full-time employees of the committee. The World Cup was a side hustle no more.

“They did outstanding work and were in the best position to keep it going,” Mr. Lasry said.

When the World Cup draw was held Friday, though, the pair were both working remotely again. Mr. Revman was at the World Cup festivities in Times Square while Ms. LaRusso attended the official FIFA event in Washington, D.C.

Now, for the next several months, the task shifts from a promise that the region will be a good host to proving it.

“I will be forever proud of what we’ve already done and to have Lauren with me, because we worked together on it for so long,” Mr. Revman said. “And there’s still a ton of work ahead.”

David Waldstein is a Times reporter who writes about the New York region, with an emphasis on sports.

The post Inside the Yearslong Push to Bring the World Cup Final to New Jersey appeared first on New York Times.