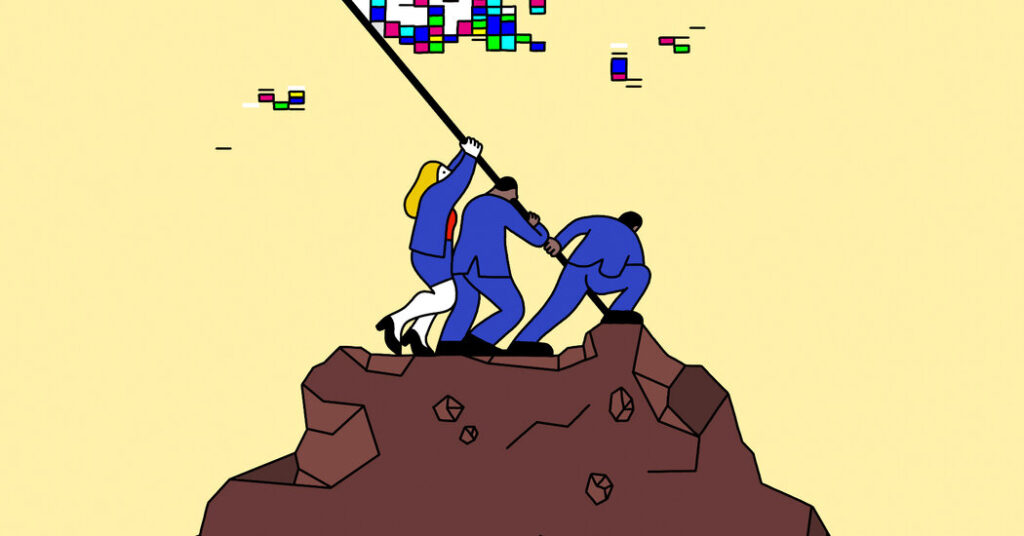

Founding a company has always been prestigious in Silicon Valley. Pivoting a struggling company is less glamorous.

So lately, as artificial intelligence has scrambled operations for many businesses, some executives are announcing that they are “refounding,” essentially rebranding, as A.I. start-ups.

In June, for example, Airtable, a project management platform, announced that “instead of just adding more A.I. capabilities to our existing platform, we treated this as a refounding moment for the company,” sharing that it would be giving A.I. features to users as a default and rolling out a new pricing model.

In October, Handshake, a careers site, announced its new business model, which includes hiring contractors to generate data to sell to large language model companies. “This is our refounding,” the company said in a blog post. “Not a second act, but the next leap in the mission we started a decade ago.”

And last month, the new chief executive of Opendoor, a real estate start-up, told investors that “we are refounding Opendoor as a software and A.I. company.” Opendoor, which did not respond to a request for comment, and Handshake both announced layoffs around the same time as their refounding announcements.

How it’s pronounced

/rē-fau̇nd-iŋ/

The leadership team at Airtable, which was early to using the term, played around with words like “relaunch” and “transformation” to describe its A.I. era, Howie Liu, the company’s co-founder and chief executive, said in an email. But it ended up choosing “the language of founding because the stakes feel the same,” he said, in the sense that current decisions will shape the next decade of the company. The term, he added, captures the broad scope of changes, unlike a pivot, which he thinks implies a change of direction after getting something wrong.

A refounding injects “start-up culture back into an existing business,” said Katherine Kelly, the chief marketing officer of Handshake. It aims to capture the energy of founding without all the risks — an approach that is “very seductive,” she said, for the tech community.

The return to an early-days mind-set can also encourage the all-out-grind approach that defines young start-ups. Handshake called its employees back into the office five days a week at the same time that it announced the refounding, Ms. Kelly said, and its leaders made clear that they “expect people to be operating with a pace and number of hours that is meaningful and will help us hit goals.” Being part of a just-founded start-up can be invigorating; executives are hoping the same will be true in a refounded one.

Though it heralds a new chapter, a refounding also involves looking at the fundamentals of a company and “reinterpreting” what has made the firm operate well in the past, said Jon Iwata, a lecturer at the Yale School of Management. Mr. Iwata, who has written about how established corporations manage such changes, predicted that “A.I. is going to cause many C.E.O.s to ponder existential questions,” and to ask, “What business are we really in?”

Once a company decides what business it’s really in — in many cases, the business of A.I. — the stakes are high. Conventional wisdom says that you can found a company only once. The refounding mind-set suggests that perhaps founders can get another go.

But after that, at least in Ms. Kelly’s view, that’s it. “If you’re really going to make people believe it at your company,” she said of refounding, “you have to put a lot of effort into it, because you only get this one chance.”

The post Don’t Call It a Pivot. These Executives Are ‘Refounding’ Their Start-Ups. appeared first on New York Times.