A secret is percolating at dinner parties, salons, and cocktail gatherings among the august New York City elite. It’s whispered in the circles of financial masters of the universe, Hollywood stars, and owners of sports teams. Have you heard about Fortell?

Many haven’t—or if they did hear, they might not have made out the words through noisy cross-conversations. Once they do know—particularly if they’re boomers—they want it desperately. Fortell is a hearing aid, one that claims to use AI to provide a dramatically superior aural experience. The chosen few included in its beta test claim that it seems to top the performance of high-end devices they’d been unhappily using.

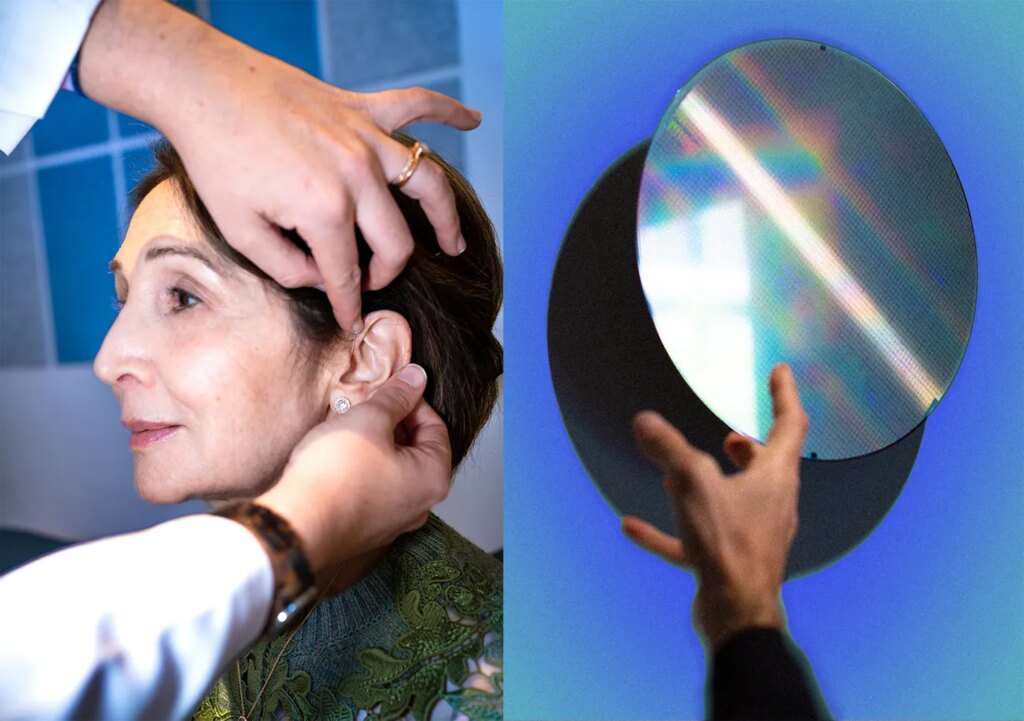

These testers have made pilgrimages to Fortell’s headquarters on the fifth floor of a WeWork facility in New York City’s trendy SoHo neighborhood, where they were fitted for the hearing aids—which from the outside look pretty much like standard, over-the-ear, teardrop-shaped devices. But the big moment comes when a Fortell staffer takes them down to street level. There, among street clatter, honking cabs, and delivery trucks backing up to luxury stores, they are asked to conduct a conversation with a Fortell worker. Two other employees stand behind them, adding their own loud discourse to the urban cacophony.

Despite the din, the testers clearly make out what the person in front of them is saying. The clouds lift. Angels croon. “This was so incredible that I burst into tears,” says Ashley Tudor, one of the seemingly few beta testers who isn’t famous or powerful (though she is married to a venture capitalist).

Among the age-related-hearing-loss set, getting into the Fortell beta test has become a weird status symbol, the aural-prosthetics version of a limited-edition Birkin bag. “This product has become a major flex for the post-70 set,” says one investor. When entertainment lawyer Allen Grubman got his—he’s buddies with an investor—he began getting calls from “very substantial” people. “They said, ‘Allen, we hear that you have these new great hearing aids,’” he says of these callers, who all wanted in. Those who finagled their way into the program include multiple Forbes 400 billionaires, a chart-topping musician, the producer of a beloved TV series, and Hollywood A-listers, both old and not-so-old. KKR private equity co-executive chair Henry Kravis raves about his Fortells, as does performer and beta tester Steve Martin.

One of Martin’s pals is actor Bob Balaban, who suffered from significant hearing damage on a movie set some years ago and was unhappy with the devices he used to mitigate the problem. Envious at Martin’s good fortune of obtaining these cutting-edge devices, he despaired that he might not get fitted himself. “God. I wish I had Steve’s hearing aids,” he told his wife. “But I think they’re movie-star hearing aids. I don’t think they’re character-actor hearing aids.” Happily, Balaban did make the cut.

The people at Fortell say they hope eventually everyone who needs one can try it. The product goes on sale this month—but at only one location, with a daunting waiting list. It might be easier to procure Marty Supreme merch. The retail price will be $6,800.

Fortell’s story begins with Matt de Jonge’s grandparents. “Four times, I watched them lose their hearing, get fancy hearing aids, and just drift away,” says de Jonge, who is Fortell’s cofounder and CEO. His grandparents tumbled down a decline that is all too familiar. At first they asked people to repeat what they said, but the repetition became annoying for both sides. Sooner or later, they stopped asking, tuning out conversations that were no longer clear to them. Ultimately, as de Jonge learned, the subsequent isolation hastened a journey toward dementia. He has remorseful recollections of holiday dinners where the grandparents were ignored by family. Including him. “I had given up on them,” he says. “I feel like I have blood on my hands.”

At the time de Jonge, who is now 37, was employed at the giant hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, working on its AI team. On nights and weekends he began to research what it might take to make better hearing aids. The current state is not ideal. While it’s a nearly $14 billion industry, the few key players have not managed to develop products that users love. (Some might disagree: WIRED’s testers have found units worth recommending.) One 2007 study, mentioned again in 2013—around the time de Jonge started looking into this—reported that 80 percent of adults between 55 and 74 who could benefit from hearing aids don’t use them, including many who actually own them. Reasons vary from cost to comfort to the perception that the aids don’t work well enough. De Jonge realized that the key problem was in the area where hearing was most important: helping people hear conversations in social settings. Most hearing aids relied on amplifying sounds and using noise reduction, which didn’t do the trick in those scenarios.

The problem was harder than it seemed. “It’s not about making sounds louder,” says de Jong. “People with age-related hearing loss have lost some of the magic of focusing on the sounds that are important to them.” The worst situations occur in restaurants and social gatherings with lots of cross conversations. That’s known in the trade as the Cocktail Party Problem. While even people with normal hearing can struggle in those settings, those with hearing loss are lost in crescendos of conversational clatter, and costly hearing aids don’t help much. De Jonge reluctantly concluded that he had no answer for it.

The exercise did motivate de Jonge to explore how technology could help solve other medical issues. He left Bridgewater and joined a startup making an AI-powered sensor called Butterfly IQ that provided “ultrasound on a chip.” He worked his way up to VP of product, and his shares in Butterfly became liquid when it went public in 2021.

Soon after, de Jonge and Cole Morris, a friend from his Bridgewater days and former college roommate, began pursuing an ambitious idea from Joshua Kushner, a key investor in health care startup Oscar Health who heads the VC firm Thrive Capital. Kushner was exploring whether he wanted to buy a working hospital and use it as a test bed for software that could make the operation exponentially more efficient. Soon after they started the planning, de Jonge and Morris were having second thoughts. “After four months talking to doctors about buying a hospital and ripping out all the software in it, I realized I might kill somebody,” he says. Around that time his aunt chided him about abandoning his original quest. The next generation in his family was already experiencing hearing loss. “Weren’t you going to build a better hearing aid?” she asked him.

That resonated with de Jonge, whose experience with Butterfly had hinted that AI could now handle bigger challenges. He and Morris told Kushner that they wanted to drop the hospital project and instead form an AI hearing aid company. Kusher immediately said he’d fund it. “A lot of people regard AI as something you’ll use to make businesses more efficient,” he says. “But people haven’t really internalized that you could use AI to make products exponentially better.”

De Jonge and Morris eventually dubbed the new company Chromatic, a name they later ditched, settling instead on Fortell. They realized that there would be two critical components in an improved approach to a hearing aid. The first would exploit the recent advances in AI for a better algorithm to selectively augment conversation. And the second would be a custom chip to process that algorithm in real time.

“Oh, man, if I could wear these to a loud coffee shop and have a meeting, it would change my life.”

Founders Fund partner Trae Stephens

The first requirement became the province of Igor Lovchinsky, who had been Butterfly’s AI wizard. He’d come to the field late in life; up until his mid-twenties he’d been a Juilliard-trained concert pianist but left the field when he became enamored with science. Lovchinsky felt that the AI claims made by some other hearing aid companies were overblown; they were simply tweaking the amplification, he says, or aiming the microphones in a different direction.

“What became clear is that what was needed is source separation,” he says. “Take an audio wave that contains both things you want to hear and things you don’t want to hear, and separate them into just speech and just noise.” Even in 2021, it wasn’t clear that this was possible. “We all have this incredible neural network in our heads honed by billions of years of evolution to recognize speech,” he says. “If you do the source separation with the slightest deviation from full naturalness, your brain will immediately hear it.”

As the company’s cofounder and chief scientific officer, Lovchinsky and his team set about using cutting-edge AI to identify the aural fingerprints of the voices directed to the wearer, clean them up, and pass them on as if delivered in a quieter setting.

Having the right algorithms wouldn’t be worth much if you didn’t have a properly engineered chip to run them. To lead its silicon team, Fortell tapped as CTO Andrew Casper, another Butterfly alum who was a lead engineer on a Google team making AI chips. Casper also wasn’t sure that his task could be accomplished. “Your ear is very sensitive to latency,” he says, noting that if the altered sounds weren’t processed in 10 milliseconds—a hundredth of a second—it would throw users into a hellish uncanny valley. “We didn’t know if it could be done in that amount of time with a high enough fidelity so you aren’t going to notice distortions.” Only then, he says, could the company move to the final challenge: “Can we even put this thing into your ear?”

It was going to take years before the startup got those things right and could even begin to test on humans. Fortunately, the $9 million initial stake, the majority of which came from Kusher, provided a long runway. “For the first few years of the company there was no hearing aid in sight,” says de Jonge. “We needed to build for ourselves to see if the science problems could be solved.”

By 2023, Lovchinsky and Casper had made significant progress on their respective missions. Lovchinsky’s team realized that separating out the voices required creating a proprietary version of what is known in the industry as Spatial AI, involving a 3D understanding of the real world. (Confusingly, they also use the nonproprietary technology, spatial AI, in their product.) “It gleans perspectives from multiple microphones and can infer the same way that healthy people can, from both ears,” he says. His team also found a way to train their AI models with huge amounts of synthetic data that emulated all sorts of conditions. “It’s specifically useful in the most challenging environments,” he says.

More rounds of funding followed, with $150 million invested so far. The B round was co-led by Antonio Gracias, known for his involvement in Tesla and the so-called Department of Government Efficiency. (He’s using that Tesla experience to provide guidance on scaling Fortell.) De Jonge gave him the street demo; the product is of special interest to Gracias because Gracias’ sister is a dentist who has hearing loss because of the constant drill noise. “Even with construction behind me, I could hear Matt clearly,” he says, “and [it] literally brought me to tears.” Gracia’s sister is now in the beta test.

Another early investor was Founders Fund partner Trae Stephens. While his general hearing is pretty good, Stephens, 42, had been noticing problems in noisy rooms. He was blown away with a demonstration. “It was honestly the best hardware demo I’ve seen in my 11 and a half years at Founder’s Fund,” he says. “Oh, man, if I could wear these to a loud coffee shop and have a meeting, it would change my life.”

Those early demos came before the chip was ready. The first testers wore an awkward rig with headphones attached to a laptop that processed the sounds. “We took people to coffee shops and restaurants and apologized to the waitstaff, explaining we were testing some hearing aid technology,” says Morris. “Mostly they let us do our thing.”

De Jonge had secretly made a list of potential high-profile beta testers. He had no idea if they had hearing difficulties, just that they had reached a certain age when many if not most people have trouble. One of those early users was KKR’s Kravis, an early Fortell investor who had been trying different hearing aids for years. He was so impressed that he wanted to increase his stake, which ultimately became $6.2 million. Kravis also offered to connect the team with some high-profile beta testers. So he sent his friend Steve Martin, a fellow art collector, to SoHo.

“I’ve tried different brands of hearing aids, and they’re good, but they’re not this good,” says Martin in a Zoom interview. He visited the team in Soho, did the street test, and was delighted when he tried it with his wife and daughter at their favorite restaurant, with de Jonge sitting with the laptop several tables away. But the clincher for Martin was a cocktail party.

“I was here in our building, and I was at a party upstairs, and I had my old hearing aids in,” he says. “I’m sitting talking to four people, and I realized I can’t understand any of them, and I go, wait, I have these new hearing aids. I went downstairs, put them in, came back, and I could hear everyone.” Now he wears them all the time, and even made a joke about hearing aids on Saturday Night Live’s 50th anniversary special. “I don’t really think about the way it used to be,” he says. “I used to dread going to a restaurant, and now I don’t.” His friend Balaban, once he got into the beta test, is similarly smitten. “This is a significant improvement over the absurdly pricey devices I’d been using,” Balaban says.

It’s a sad fact that some Medicare and many health insurance plans do not cover hearing aids, a policy that dooms millions to an aural bardo of conversational exclusion.

Other machers aren’t public, but de Jonge assures me they are mostly names invoked in boldface type. Since there are only a few dozen beta units, this means that some powerful people have been shuttled to a waiting list. Balaban’s wife, Lynn Grossman, recounts attending a Labor Day dinner with over 100 people, generally of a certain age, in a private room in a restaurant, thinking that her husband and another guy—a famous CEO in the fashion world—were the only ones who could hear, because of Fortell. “After, I think Bob got 12 or 14 emails saying, ‘How do I get those hearing aids?’”

Now that the product is launched, Fortell will sell hearing aids in a single clinic on Manhattan’s Park Avenue. It’s decked out like a posh lounge, with the devices on display in a tasteful presentation that’s straight out of the Apple retail playbook. Hanging on the wall is a silicon wafer with the circuitry of the custom chips. In the early stages, his staff of four audiologists will serve only a couple of dozen customers a week, to make sure everything goes smoothly. In any case, while ramping up production, the supply will be limited.

This is great for Fortell, but it seems de Jonge’s initial impulse to usher everyone’s grandparents into the land of the hearing is in danger of being limited to the one percent, which doesn’t exactly qualify him for a Salk medal. When I ask de Jonge how his invention can scale to change life for the masses, his replies, whether due to secrecy on future plans or just not having a good answer, seem hand-wavy. In his defense, Fortell has resisted the temptation to jack up the traditional price of premium hearing aids—the $6,800 is actually a bit less than some other medically prescribed hearing aids. (As with other high-end hearing aids, the price is part of a package that includes fitting and support from professional audiologists.) Still, even that defensible price tag limits adoption; it’s a sad fact that some Medicare and many health insurance plans do not cover hearing aids, a policy that dooms millions to an aural bardo of conversational exclusion, isolating them from loved ones and hastening dementia.

It’s unclear whether Fortell technology might find its way into the less expensive over-the-counter hearing aids available today, which became possible via a Biden-era shift in regulation. These include Apple’s AirPods Pro 2 devices and entries from other consumer electronics brands, which are generally known to help those with hearing loss but not as much as high-end devices that are paired with professional support. The Fortell proposition requires careful testing and tuning, continuing for some time as wearers get used to the devices. In any case, that white-glove approach will consume Fortell’s efforts for the next year and more. Expansion will come by opening clinics in a few select cities, and only later will Fortell consider scaling to allow others to sell the technology.

By now you’re probably wondering … who is paying this WIRED reporter to pump up the prospects of a new startup? Is it really that good? It’s hard to measure hearing quality, but Fortell has set out to prove scientifically that it has a better solution to hearing loss. It contracted researchers in NYU Langone’s audiology and neuroscience departments to consult on a blind experiment comparing Fortell with the leading AI-powered hearing aid competitor, a Swiss company called Phonak, whose devices retail for $4,000 and is considered the gold standard in AI hearing products. (In the study, Phonak isn’t mentioned by name and is identified only as the control hearing aid group.)

The test matched performance in environments where noise was coming at random intervals from three directions—kind of an emulation of the Cocktail Party Problem. “This is a configuration that’s particularly good to show the advantages of this aid, because what it does is actually extracting the various signals and getting rid of some of them,” says Mario Svirsky, the Noel L. Cohen Professor of Hearing Science at NYU School of Medicine, who consulted in the study (and was paid for his time).

Svirsky says the test and its goals were set out in advance. If it showed that Fortell notched a 4-decibel increase over its rival in boosting the desired signal, it would be a home run. But when they ran the study, the difference reported between the two devices was 9.2 dB in Fortell’s favor. “The results were overwhelming,” he says. “I’ve never seen such a categorical result in my career.” In one chart, the line representing the hearing improvement from Fortell virtually towered over the Phonak line. The study concluded, “In the most challenging multi-talker environment participants had 18.9X higher odds of understanding speech versus the top AI hearing aids on the market today.”

Naturally, I sought comment from Phonak about those results. Michael Preuss, the lead audiologist for Phonak’s AI platform, has been wearing heading aids since he was 3 years old. Phonak, he says, has been in the business for 75 years and has been working with AI in its products for the last quarter century, and for the last seven years has pursued the idea of producing an AI chip—just like Fortell. Phonak, too, has spent years developing and testing its AI system, which rolled out last year to what the company describes as acclaim and adoption. When I tell Preuss about how some startup he never heard of trounced his product in a head-to-head test, he seems unruffled. “We have seen in the past that there is no industry standard in how you set up these studies and how you do these kinds of measurements,” he says. “You can design studies to enhance your own performance.” To be sure, Fortell did set up conditions that played to its strengths. But Svirsky says that those conditions were the ones that matter to hearing aid wearers. Also, unlike almost all studies performed by hearing aid companies, Fortell has submitted its work for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Still, because of what seemed to be cherry-picked conditions—and the study’s funding coming from the company itself—skeptical observers might not see the test as a slam dunk. And who knows, perhaps all those delighted Fortell beta users who refuse to return the units after their test period are experiencing kind of an insidery placebo effect. It also could be that the extra attention given to beta testers encouraged users to be more diligent about visiting the audiologists multiple times for perfect tuning. So I decided to test the Fortell aids for myself.

I have had a hearing loss problem for years. I blame it on an ear-shattering 1969 Who concert (worth it), but my doctor says it’s more likely a combination of childhood ear infections and, well, getting old. I am an unsatisfied customer of a high-end hearing aid. So I was eager to test Fortell’s wares, starting with the street demo. No, I did not burst out in tears. But I was cautiously impressed. Once I got fitted and fine-tuned—this involved a hearing test and several sessions with a Fortell audiologist—I began using the aids daily. The comparison with my old devices wasn’t head-to-head, but I sensed noticeable improvement.

Fortell is no miracle: In really noisy conditions, things are still hopeless. But to be fair, even people with perfect hearing are usually shouting at each other in those situations. (Who told restaurants that Led Zeppelin–level noise was the perfect accompaniment to dining?) Absent, say, a DJ and a wall of speakers, Fortell really did crack the Cocktail Party Problem. Compared to the expensive hearing aids I was using, I could follow more conversations during restaurant meals. I found myself comfortable with using them all day, whereas I couldn’t wait to take off the ones I had paid $8,000 for. (Apologies to Phonak—I haven’t tried those.) The biggest test was how well I could hear my wife, whose dulcet voice is sometimes the hardest one for me to make out. Using these new devices, I am less likely to respond to her trenchant observations with the word “What?”

Bottom line: Now that Fortell is open for business, I’m going to ditch my present units and drop almost seven grand to buy a pair. If I can get on the list.

Let us know what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor at [email protected].

The post New Hearing Aid Company, Foretell, Brings in Steve Martin and Others as Fans appeared first on Wired.