PORTLAND, Maine — When the ads sullying District Attorney Jonathan Sahrbeck began hitting mailboxes and televisions about three weeks before the 2022 Democratic primary, he and his opponent were equally stunned.

Like many modern-day campaign attacks, the ads came from an independent political committee bankrolled by a billionaire — in this case, the former hedge fund manager and liberal philanthropist George Soros, who set out a decade ago to elect district attorneys who would steer drug offenders and juveniles toward rehabilitation instead of prison, oppose cash bail for minor crimes, and crack down on police misconduct.

As the ads battered Sahrbeck, his challenger, fellow Democrat Jacqueline Sartoris, felt as if her campaign had been hijacked. Her father, a staunch Republican averse to Soros’s left-wing agenda, urged her to personally repudiate him. Supporters asked questions she could not answer about hard-hitting allegations in the ads. Reporters called for comment.

Sartoris decided to air a radio spot distancing herself from the Soros-funded campaign. At the bottom of the script, she added the Serenity Prayer — not to read aloud, but to remind herself to “accept the things I cannot change.”

The $384,000 dropped by the Soros-backed political action committee — a minuscule investment for a man with an estimated net worth of $7.5 billion — amounted to five times the money raised collectively by both candidates. (Under Maine law, the PAC could not coordinate its activities with Sartoris.)

Sahrbeck is sure the ad blitz cost him his job, and even Sartoris wonders: Did the voters pick her, or did Soros?

“You go from thinking you are driving your own car to realizing you got the play wheel,” she said. “I will always wonder if we would have won on our own steam.”

The district attorney race in Cumberland County, Maine, is among dozens around the country that Soros has bent to advance his criminal justice agenda, showing how a single billionaire can change the course of public policy. The vast fortunes of the super-rich are particularly potent when applied to downballot races, where a barrage of campaign ads can leave deep impressions on voters who are often less familiar with the candidates than they are with those at the top of the ticket.

Over the past decade, the Soros-backed Justice & Public Safety PAC and affiliated committees have built a cost-effective and winning record. These entities spent roughly one-fifth of Elon Musk’s $294 million investment in the 2024 election, spreading that money across at least 62 primary and general election races and winning 77 percent of the time, according to a Washington Post analysis and data provided by the PAC. These district attorneys command extraordinary authority to pick and choose who enters the criminal justice system and for how long.

“Dollar for dollar, George Soros’s involvement in these races has made a bigger change in criminal justice across America than anything else,” said Jason Johnson, president of the Law Enforcement Legal Defense Fund, a conservative nonprofit that opposes Soros’s intervention in district attorney races. “His money has completely upended these elections.”

That Soros has spent money on only a fraction of the races that elect the roughly 2,400 district attorneys across the country speaks to his outsize impact. In big cities and smaller suburbs, in counties that never before elected an African American or a woman as a top law enforcement official, Soros-backed prosecutors have redefined the profile of a district attorney, contending that hard-line law-and-order policies that disproportionately incarcerated poor Blacks and Hispanics were straining prison budgets, devastating low-income communities and failing to keep the public safe.

“I think we started a movement,” said longtime Soros spokesman Michael Vachon in a Midtown Manhattan office with a sweeping view of the city. “Public safety and justice can go hand and hand. The knee-jerk, so-called tough-on-crime philosophy has been discredited in many communities.”

But one billionaire’s ambition comes at a cost, campaign finance reform advocates say. Downballot races have turned into big-money brawls that polls and political science show have eroded public faith in government. Some prosecutors who face better-funded Soros-backed contenders bow out, leaving voters with fewer choices. And while voters can hold candidates accountable for misleading attacks on their opponents, billionaires like Soros do not have to answer to the electorate.

“When heavy-handed billionaires equate democracy with their personal ideology and drop a ton of money picking candidates and destroying others while the rest of us are left as bystanders, that’s not democracy,” said Jeff Clements, CEO of American Promise, a nonprofit that advocates stronger campaign finance regulations. “It’s leading us to disaster because of the level of toxicity and take-no-prisoners warfare. The damage is systematic.”

Soros, 95, who was born in Hungary to a Jewish family that survived the Nazi occupation, is retired and no longer participates in media interviews, Vachon said. His philanthropic network, the Open Society Foundations, has given away billions of dollars to humanitarian and democratic causes all over the world. But it is Soros’s super PAC, not the foundation, that funds district attorney races and other campaigns. His son Alex, who now chairs the foundation and runs the super PAC, also declined an interview request through Vachon.

Unlike many wealthy donors, who funnel money through nonprofits that don’t publicly disclose their contributors, Soros has contributed to super PACS that publicly report their donations and expenses.

“I have done it transparently, and I have no intention of stopping,” Soros wrote in the Wall Street Journal in 2022. “The funds I provide enable sensible reform-minded candidates to receive a hearing from the public. Judging by the results, the public likes what it’s hearing.”

Soros also has given millions of dollars to support limits on campaign spending, and in 2002, he backed the last major campaign finance legislation passed by Congress, known as McCain-Feingold. But court rulings since 2010 that unleashed unlimited contributions to super PACS laid the groundwork for billionaires like Soros to spend freely to promote their pet issues.

“I do think we would be better off if we limited the influence of money in politics, but the laws are what they are,” Vachon said. “We play by the rules.”

Soros’s commitment to funding district attorney candidates dates back to 2014. The Black Lives Matter movement was ascendant following the fatal shooting in 2012 of a Black teenager, Trayvon Martin, and the recent deaths of two Black men at the hands of police, Eric Garner and Michael Brown.

Over dinner that fall at Soros’s home on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, Christopher Stone, then president of the Open Society Foundations, raised the idea of backing progressive prosecutors. Stone pointed to signs of change in a country that had waged a decades-long war on drugs: San Francisco’s district attorney was promoting a statewide referendum that would downgrade some minor, nonviolent drug crimes to misdemeanors, while the first African American district attorney in Brooklyn was easing off prosecution of minor marijuana crimes. Soros had long supported efforts to decriminalize marijuana, and he and Vachon were intrigued by the idea of prosecutors upending the tough-on-crime playbook.

“It was a watershed moment,” Stone said. “There had long been only one way to be a prosecutor, and that was to be tougher than whomever you were trying to follow or replace.”

Stone recommended that Soros reach out to Whitney Tymas, a Black lawyer who had worked in many corners of the criminal justice system, including as a public defender, prosecutor and policy expert. One of her first trips working for the Soros-backed effort was to Caddo Parish in northwest Louisiana, which reported the state’s highest death sentencing rate per homicide in the previous decade, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, a nonprofit that tracks capital punishment.

On a tour with a civil rights activist, Tymas observed the large live oak tree in front of the courthouse that reminds locals of the Reconstruction-era lynchings in what was known as “Bloody Caddo.”

“That always stands out to me as a memory that exemplifies the terror and history of the criminal justice system and the opportunity we had to make change,” she said.

Tymas hit the ground running in 2015, helping elect three Black Democratic district attorney candidates in Louisiana and Mississippi, including the first Black district attorney in Caddo Parish in a race that saw increased voter turnout. The following year, the super PAC notched eight victories in seven states. “We learned that the door could open,” Tymas said, “and then voters kicked the door in.”

One winning candidate in 2016 was Darius Pattillo, a Black Democrat who campaigned on improving pretrial diversion programs and community outreach in an Atlanta suburb that had never elected an African American as district attorney. His Republican opponent, Matthew McCord, a municipal court judge, learned from a reporter that the Soros PAC was spending about $100,000 against him.

McCord called a couple of candidates who had run against Soros’s money before. They advised him to get out of the race.

“The amount of money and the negativity was not going to be good for my family or my community,” McCord said. “It was the hardest decision I ever had to make.”

McCord’s departure from the campaign meant Pattillo ran unopposed. “How is that democratic?” McCord asked.

One of the people who advised him to give up was Albuquerque attorney Simon Kubiak, a Republican who had recently dropped his own bid against a Soros-backed Democrat. In a statementto local reporters at the time, Kubiak lamented facing “unlimited resources and support from a multibillionaire from another country.” (Soros is an American citizen.)

“That’s just part of the process. People drop out of races for many reasons,” Tymas said. “Our spending has allowed people who never would have had a shot to communicate to do so.”

Over the next few years, Tymas crisscrossed the country with a carry-on suitcase as the super PAC helped elect a mold-shattering slate of prosecutors, including the first female district attorney in Polk County, Iowa, a Persian American woman who had worked as a public defender in Northern Virginia and the first Black district attorney in Fort Bend County, just outside Houston. In Philadelphia, money from a Soros-backed PAC helped civil rights lawyer Lawrence Krasner overcome opposition from the police union to become district attorney. Soros also had a hand in electing Florida’s first Black prosecutor, Aramis Ayala. She later received a noose in the mail.

Fort Bend County District Attorney Brian Middleton, who narrowly lost a predominantly self-funded race for county judge two years before his 2018 election, is now serving his second term.

“There were factions in the community that did not want to see a Black man as district attorney,” he said. “Soros provided a huge boost.”

Soros’s largesse frequently inspires other liberal donors and wealthy conservatives to get involved in district attorney campaigns, pumping up traditionally lackluster fundraising for local races. In Norfolk, Commonwealth Attorney Ramin Fatehi, whose 2025 campaign received about $435,000 from two Soros-funded political committees, said the combined spending by him and his Democratic primary opponent broke records for a citywide commonwealth attorney race. “It’s absurd,” said Fatehi, who also loaned his campaign more than $200,000. “But the money allowed me to communicate with real people in a completely broken campaign finance system.”

Two weeks after a Soros-backed PAC began spending on behalf of Democratic candidate Alicia Walton in the Little Rock area, she was the target of attack ads that local media tiedto Wisconsin billionaire and shipping supplies magnate Richard Uihlein. Walton, who is not related to the Arkansas family behind Walmart, spent only about $25,000 on the campaign. She was amazed to see two out-of-state billionaires duking it out in central Arkansas, collectively spending more than $350,000. She lost.

“It got nasty, and I was very shocked,” Walton said of the 2022 campaign. “This is Pulaski County, Arkansas, not Chicago.”

By that time, conservative groups and candidates had built a counteroffensive that blamed Soros-backed prosecutors for spikes in crime in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. (Homicides did surge in 2020 and 2021. But it was a nationwide trend not confined to areas with more liberal prosecutors, and experts have said there was no single explanation.) District attorney candidates — including some who did not directly benefit from Soros support — were denounced as “Soros prosecutors” allegedly beholden to the liberal billionaire and dangerously soft on crime.

In many states, the Soros-backed PACs spend money independently and are barred from coordinating with district attorney candidates. That’s not always apparent to voters, however, and Soros’s opponents have sought to weaponize his image as a well-known patron of left-wing causes.

His political profile in the U.S. has been rising since 2004, when he gave millions of dollars to groups opposing George W. Bush’s reelection, prompting a top Republican operative to lament, “George Soros has purchased the Democratic Party.” Soros became a major funder of the Democracy Alliance, launched as a counterweight to the network funded by conservative billionaires including Charles and David Koch that had secured Republican victories in state and federal elections. He ranks fifth among the top billionaire political donors in the last 10 years, having given more than $321 million to federal and state candidates and committees, according to a Post analysis.

His wealth and Jewish background have made him a frequent target of antisemitic conspiracy theories in the U.S. and abroad that cast him as a puppet master manipulating the media and financial markets. President Donald Trump has repeatedly accusedSoros and his son of supporting violent protests, without evidence, and has threatened them with criminal charges.

“Soros has become a bogeyman,” said Patrick Gaspard, who served as president of the Open Society Foundations after Stone. “There is a heat-seeking nature to the way the right responds to anything Soros is involved in, and it gets magnified in the media and can play out in complicated ways.”

When President Joe Biden tapped Scott Colom, a district attorney in Mississippi, to be a federal judge, Rep. Cindy Hyde-Smith (R) derailed the nomination, in part because a Soros-backed PAC had boosted his election years earlier. Colom sought to defuse the situation by insisting in a 2023 letter to Hyde-Smith that he never requested the support. “I have never met Mr. Soros, nor have I ever spoken with him,” he wrote, using boldface and underline for emphasis, to no avail. Colom recently launched a U.S. Senate campaign against Hyde-Smith.

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) went so far as to suspend two Soros-backed Democratic prosecutors in a two-year period as part of a crusade against what he described as “woke” ideology. (One of the prosecutors won her job back in 2024, while the other lost a bid to regain public office.) And in Texas, where Soros has boosted about half a dozen prosecutors, Attorney General Ken Paxton has promoted a campaign against “rogue district attorneys.” A group funded by Musk that tried to dislodge one Soros-backed district attorney in Texas last year sent out mailersfeaturing a bloodied teddy bear and accusing him of “filling Austin’s streets with pedophiles & killers.”

Amid the backlash by conservatives seeking to tie Soros-backed prosecutors to rising crime, some failed to win second terms. In the most high-profile setback, George Gascón, who had survived recall attempts as the Los Angeles district attorney, was defeated by a former federal prosecutor in 2024. At the end of last year, Musk appeared to be planning a broad counterattack against Soros-supported prosecutors, but his plans for the 2026 elections are unclear.

“Soros figured out a clever arbitrage opportunity,” Musk posted on X in 2023. “The many small political contests, such as DAs & judges, have much higher impact per dollar spent than the big races, so it is far easier to sway the outcome.”

Sahrbeck, the Maine district attorney whom the Soros PAC targeted, had been a prosecutor in the Cumberland County human trafficking unit before he won election in 2018. He was a middle-of-the-road Republican who had voted for Green Party candidate Ralph Nader in 2000, interned for Sen. Olympia Snowe (R-Maine) in college, and donated $50 to the Republican National Committee when Sen. John McCain (R-Arizona) ran for president in 2008.

But after his boss announced she would retire, Sahrbeck registered as a nonpartisan candidate for district attorney. Prosecutors, he thought, should demonstrate independence from political parties. In an unexpected twist, both of his opponents, a Democrat and a Republican, pulled out of the race in the homestretch. Their names still appeared on the ballot, leaving Sahrbeck the winner, with only 26 percent of the vote. “It made me realize that not many people are paying attention,” he said.

That’s not the way Sartoris, then a prosecutor in a nearby county, viewed the election results in her hometown. To her, Sahrbeck had won by happenstance and without a mandate from the voters. And as a lifelong Democrat, she felt she could better represent the liberal community around Portland.

She was taken aback when Sahrbeck registered as a Democrat shortly before he filed to run for reelection in 2022.

“My party membership has come at some serious personal cost for me,” said Sartoris, whose family is Republican. “It means something to me in terms of my principles, and I did not think Jonathan was making a principled choice.”

Sahrbeck said his politics had shifted after serving as district attorney and immersing himself in the drug treatment community. He also said he received encouragement from some local Democrats concerned that his last race indicated that voters were wary of voting for someone without a party affiliation.

“The work that I had been doing aligned with Democratic ideals,” he said. “I wasn’t perpetrating a fraud on anybody.”

The Soros-funded attacks in the 2022 campaign began around Memorial Day weekend, a few weeks before the June 14 primary. “JUST THE FACTS about our flip-flopping District Attorney,” read one mailer, noting his party switch and donation to the Republican Party.

“What was a sleepy campaign for district attorney all of a sudden turned into a negative campaign against me,” Sahrbeck said.

Sahrbeck sought to discredit the $384,000 in spending as “dark money,” but the Soros mailers contained the required disclaimer with the name of the super PAC and additionally disclosed that George Soros was the top funder of that political committee.

Sartoris didn’t think she needed the help, though she couldn’t afford to pay a campaign manager. She raised less than $23,000 — only half as much as Sahrbeck — but it was enough to send postcards to about 24,000 die-hard Democrats in the county. Her mailer also highlighted Sahrbeck’s party switch, but she cringed at the Soros mailer’s snarkier tone. “Fake plant. Fake lobster. Fake Democrat,” read one flier over images of a plastic plant, toy lobster and Sahrbeck’s face. The Soros-backed ads also made allegations about Sahrbeck’s record in office that Sartoris could not defend.

“It was frustrating to have to answer for something I had no control over, for choices I wasn’t making, for language I wasn’t using,” she said.

However, Sartoris said she would not have received close to twice as many votes as Sahrbeck if not for Soros’s intervention.

Late last year, Musk circulated a list of six district attorneys up for reelection, including Sartoris, that got millions of views on X. The social media post unnerved one of Sartoris’s children, who insisted she hang curtains in her home for more privacy.

She sewed the drapes herself.

Read the Billionaire Nation series

- How billionaires took over American politics

- The forgotten court case that let billionaires spend big on elections

- The top 20 billionaires influencing American politics

- We asked 2,500 Americans how they really feel about billionaires

About this story

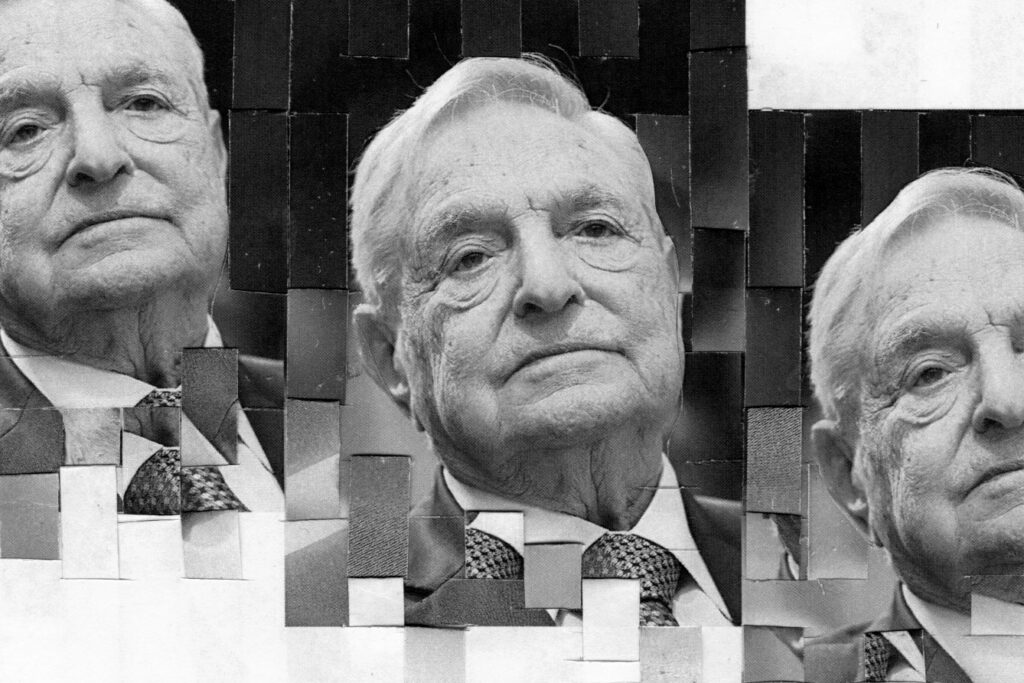

Reporting by Beth Reinhard and Clara Ence Morse. Design and illustration by Tucker Harris. Illustrations contain prop paper money.

Design editing by Betty Chavarria. Photo editing by Christine T. Nguyen. Editing by Nick Baumann, Patrick Caldwell, Wendy Galietta and Anu Narayanswamy. Copy editing by Christopher Rickett.

The post How George Soros changed criminal justice in America appeared first on Washington Post.