The Nov. 24 front-page article “Hiroshima survivor finds her vision under threat” shone much-needed light on the threat of nuclear annihilation. It shared the gut-wrenching story of Koko Kondo, a Hiroshima survivor, who dedicated her life to sharing her painful history as “the best way to prevent it from repeating itself.” Her message about the damage to Japanese people has received vital international attention on the need for nuclear disarmament, but there is another survivor story about effects of nuclear weapons development and testing on Americans that remains largely unknown: the harm sustained by people living downwind of nuclear weapons tests.

My family’s history is a dramatic example of how the nuclear weapons program harmed people in our own country and abroad. I lived in Salt Lake City with four of my siblings during the testing of these weapons. Unknown to anyone, fallout from bomb tests in Nevada coated the hills and valleys around the city. We played in the radioactive dust, and cattle ate grass coated with it, which contaminated our milk and meat. Radioactive pollution coated our fruits and vegetables. The resulting contamination will remain as “forever chemicals” in this beautiful city and other downwind areas across the country.

Seventy-five years later, only two of our family members are still living, and both of us have radiation-related cancers. These cancers doomed three of our siblings in early middle age. The curse has followed our family into another generation. One niece was born with missing teeth, and one nephew is missing the lower half of his right arm.

While Americans grieve for the people harmed by atom bomb attacks on Japan, untold thousands of “downwinders” pray that our stories will deter the Trump administration’s recently announced plan to resume testing nuclear weapons. They pose a threat to people everywhere.

Mary Yakaitis, Rockville

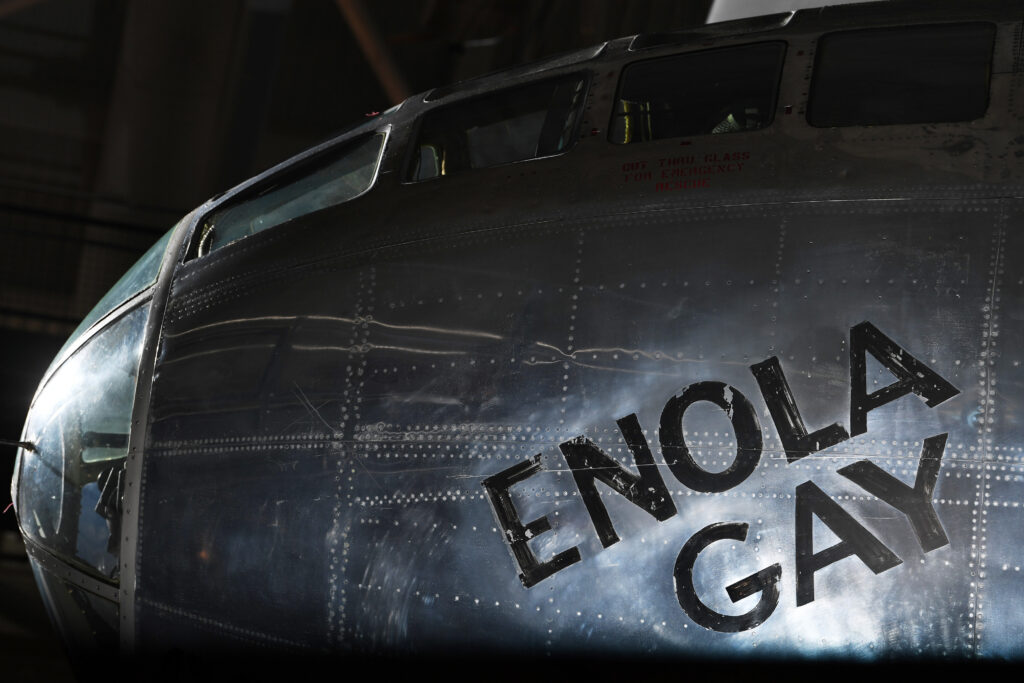

Technological advances in weaponry lowered the threshold for the ability to commit wartime atrocities such as the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Capt. Robert Lewis and the rest of the Enola Gay’s crew would not have been able to exterminate tens of thousands of defenseless Japanese civilians if the homicides required face-to-face encounters. Instead, the advent of nuclear weapons enabled one pilot to obliterate a city nearly risk-free at 31,000 feet. Our species’ survival is more and more a race between moral scruples and omnicide.

Bruce Fein, Washington

The writer was associate deputy attorney general under President Ronald Reagan.

Update this cancer screening system

The Nov. 24 online news article “Why screening for the deadliest cancer in the U.S. misses most cases” captured what patients and advocates have been saying for far too long: Our lung cancer screening system is not meeting the needs of the people it is supposed to protect.

Stories like that of Jessie Creel, a healthy 42-year-old never-smoker diagnosed at Stage 4, are devastating, but they are not unusual. Every day at GO2 for Lung Cancer, we hear from families who were told they did not qualify for screening, only to learn they had advanced disease. The new data highlighted in the article confirm what our community experiences firsthand. The criteria are too narrow, too limited and out of step with who is actually developing lung cancer today.

As the article noted, women, minorities and people who never smoked were disproportionately excluded from research. Thus they have a greater tendency to be diagnosed at a later stage of the disease, when treatment becomes far more complex and outcomes are significantly worse.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should update screening eligibility in ways that mirror evidence-based guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Cancer Society. Their approaches take a broader view of risk and stay in sync with what patients and clinicians see every day, including family history, lung disease, residential radon exposure, occupational hazards and environmental exposures.

Until the United States adopts an expanded approach to lung cancer screening, updating eligibility to reflect today’s science is essential. Lives are at stake.

Laurie Ambrose, Washington

The writer is president of the nonprofit GO2 for Lung Cancer.

Hand-wringing over hand dryers

I can relate to the sentiments in the Nov. 27 editorial “The scourge of automatic hand dryers.”

My grandson and I visited Japan several years ago. While we were having lunch at a countryside lake, I used the restroom. After washing my hands, I noticed there were no paper towels or hand dryers. I must have looked perplexed when a nice lady opened her bag and pulled out what looked like a small washcloth and handed it to me. I was puzzled, but I dried my hands, thanked her and returned to my table.

I asked our hostess about this. She explained that many restrooms do not have dryers or towels. Traditionally, men and women carry their own small towels, known as tenugui, which translates to “hand wipe.” I now have my own portable hand dryer, which comes in handy for a variety of situations.

Pamela Kincheloe, Manassas

The post My family suffered after U.S. nuclear tests. Don’t resume them. appeared first on Washington Post.